No one likes to be criticized, especially thin-skinned government officials such as our current president, who lashes out against opposition and dismisses dissent as the sinister product of the so-called deep state. But the freedom to question, even to rebuke, an elected official or otherwise to speak one’s mind is protected by the First Amendment, which seems fairly sturdy. That wasn’t always the case: not long after the US Constitution was ratified and the Bill of Rights adopted, Congress passed the four infamous laws known as the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. They explicitly muzzled criticism of government policies and officials, and sadly demonstrate that not a few founding Americans could be petty, shortsighted, and more than willing to prosecute speech they didn’t much like.

This shameful legislation included the Naturalization Act, which extended the waiting period for US citizenship from five to fourteen years and required foreigners to register within forty-eight hours of their arrival in the US. (In 1802, the less restrictive Naturalization Law reduced the waiting period to five years as long as “aliens” declared their intent to become citizens three years in advance.) The Alien Friends Act permitted the president to deport noncitizens at his sole discretion—if, for instance, he considered them to be “dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States, or shall have reasonable grounds to suspect [they] are concerned in any treasonable or secret machinations against the government.” (Opponents of the bill jested without humor that the president could expel someone if he or she was merely “suspected of being suspicious.”) The Alien Friends Act expired two years after its passage, unlike the Alien Enemies Act, which permitted the arrest and deportation of male “alien enemies” during wartime and which, in modified form, remains in effect today.1

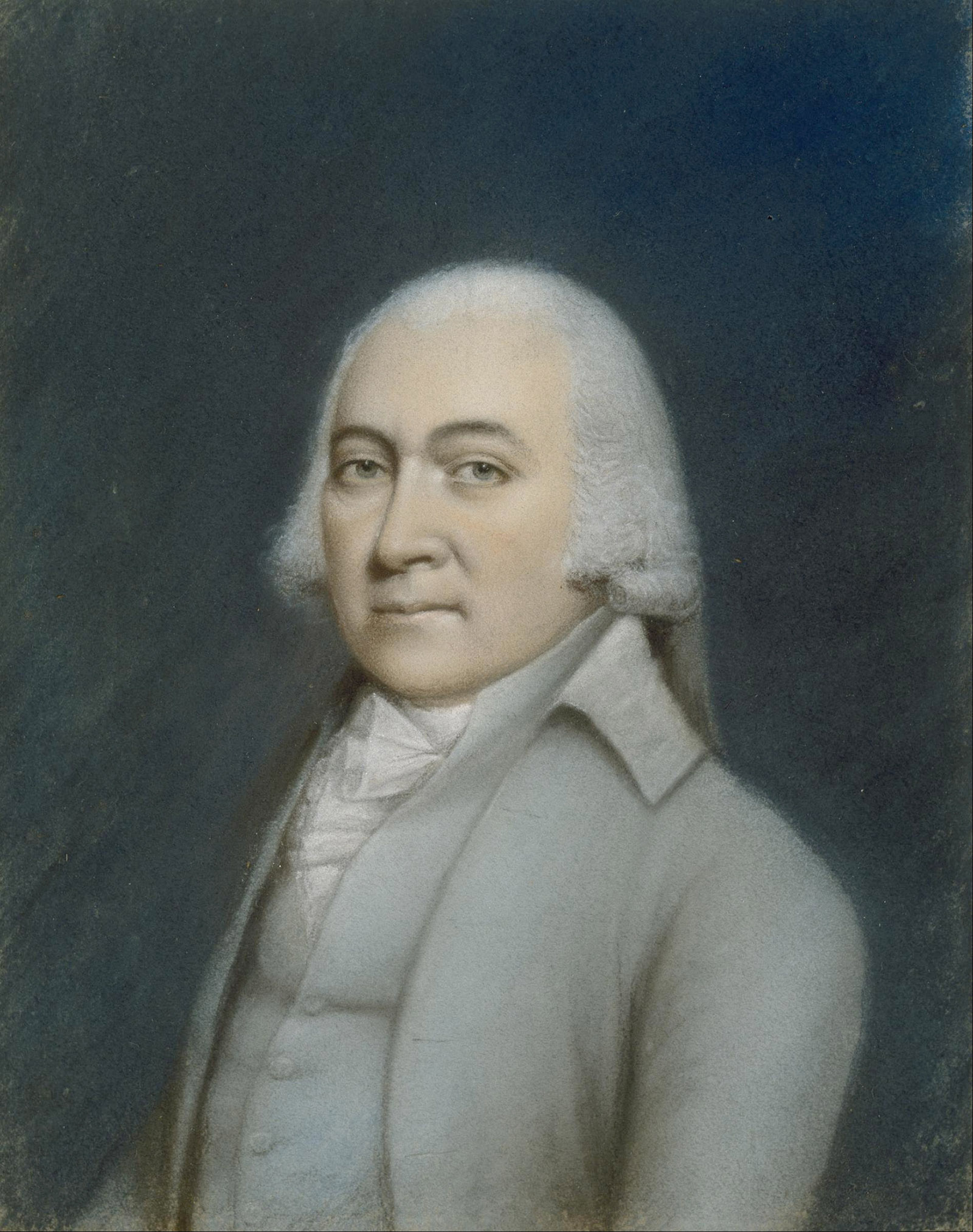

Then there was the disgraceful Sedition Act, which outlawed the speaking, printing, publishing, or assisting in the publication of “false, scandalous and malicious writing,” particularly against the Federalist administration of President John Adams, though it was perfectly acceptable to castigate the vice-president, Thomas Jefferson, the lone Republican in high governmental office. (The Sedition Act also had an expiration date: March 3, 1801, the day before the inauguration of the next president.) The Federalists tended to attribute a baleful motive to any Republican criticism—and vice versa. Federalist newspapers vilified Republicans as “a nest of traitors,” while Republicans slammed Federalists as Tory royalists.

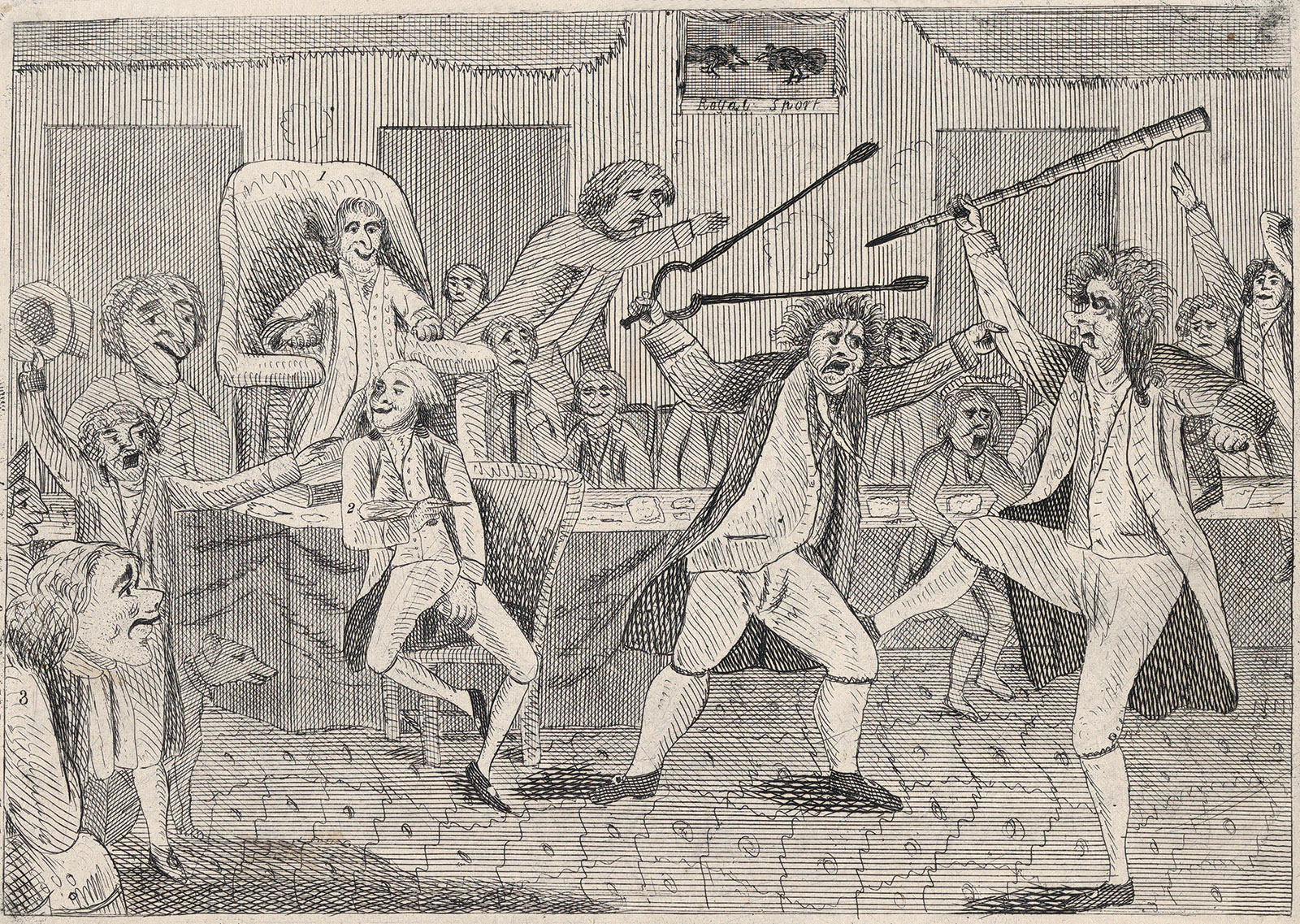

Mud-slinging is one thing; criminalizing free speech is altogether different, as Wendell Bird writes in Criminal Dissent, an exhaustive taxonomy of the prosecutions that took place under these high-handed laws. Doggedly scouring federal court records as well as the papers of such notorious partisans as Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, Bird persuasively argues that the Federalists’ attempt to squash opposition and the free flow of ideas was even more nefarious than we thought. He counts not the usual fourteen confirmed Sedition Act prosecutions (and anticipated prosecutions) but fifty-one, and not fourteen defendants but 126. This means there were many more victims of this legislation than we knew, including newspapers, editors, and ordinary people.

Since Bird is mainly concerned with the enforcement of these draconian acts and their clear violation of civil rights, he is at pains to report on every case he uncovered. Unfortunately, though each was of enormous consequence to specific individuals, the encyclopedic and repetitive nature of Bird’s book tends to dull the awful force of the legislation and its near-fanatical execution. Nonetheless, his compendium of prosecutions offers other historians and critics a comprehensive, reliable index to the people hounded by these laws and the newspapers that shut down because of them.

And Bird effectively sketches the circumstances that gave rise to these acts. George Washington may have kept the nation free of foreign entanglements, particularly the war between Britain and revolutionary France, but after the US signed the Jay Treaty in 1794 to ensure peace with Britain, the French, who felt betrayed, began capturing American ships. Hoping to avert an outright conflict but eager to protect American vessels, President Adams dispatched three commissioners to Paris to come to a peaceful solution. But the French envoys (known only as X, Y, and Z) solicited bribes from the Americans in exchange for a meeting with French officials, and when news of this was leaked (the “XYZ affair”), war hysteria gripped the nation. It especially gripped the extremists in Adams’s cabinet and in Congress, so much so that Vice President Jefferson worried that “the madness of our government” might prevent “whatever chance was left us, of escaping war.”

Actually, the country was more or less primed for the hysteria, especially when the envoy known as Y alleged the existence of a “French party in America.” Many Federalists believed that the French were plotting an American reign of terror with the assistance of domestic “Jacobins.” Secretary of State Pickering, among others, was grimly convinced that the French were fomenting a slave insurrection in the South, and former secretary of war Henry Knox thought the French might bring 10,000 “blacks and people of color” to incite a rebellion. Passions ran high. So did paranoia.

Advertisement

Out of this unpleasant cauldron, clear distinctions between the two main political parties emerged—so clear, in fact, that each often defined itself in hostile opposition to the other. Many Republicans considered Federalists, who believed in a strong central government, to be a “Monarchical party,” as James Madison branded it, in cahoots with Britain and prepared to betray the principles of the American Revolution. Federalists frequently considered Republicans, who favored a decentralized democracy, as the party of anarchy, in league with the excesses of the French Revolution.

Although Federalists controlled both the House and the Senate, Congress did not in the end authorize a war. It did, however, bolster the navy, create a provisional army, suspend commerce with France, and raise funds for the military through a direct tax on property. And it passed, by a narrow margin (44–41), the Alien and Sedition Acts, which aimed to suppress any criticism of the Adams administration, either from disloyal “internal foes” or from “aliens,” particularly the French. In other words, these acts legalized xenophobia, paranoia, censorship, and repression. But according to Bird, the Republicans understood just what was at stake: the Sedition Act violated the right to free speech. New York representative Edward Livingston and Pennsylvania representative Albert Gallatin squarely framed the issue: the act was “an abridgment of the liberty of the press, which the Constitution has said shall not be abridged.”

The Federalists relied on the common- law arguments of Sir William Blackstone and his influential Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765–1770), which defined freedom of the press as “laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published.” That is, you’re free to print your newspaper but not free from prosecution of its “criminal matter when published.” Similarly, what Blackstone called the dissemination of “bad sentiments, destructive of the ends of society” might well be considered criminal. South Carolina representative Robert Goodloe Harper, a sponsor of the Sedition Act, put the matter this way: freedom of the press did not allow “sedition and licentiousness.”

Republicans forcefully pushed back, arguing that the First Amendment had displaced Blackstone and defined freedom of the press more broadly. Virginia representative John Nicholas wanted to know where Federalists “drew the line between liberty and licentiousness,” noting that “the General Government has been forbidden to touch the press.” The editors of a Republican newspaper in New York City said that “without freedom of thought, there can be no such thing as wisdom; and no such thing as public liberty, without freedom of speech; which is the right of every man.” After all, how can an electorate arrive at an informed decision when choosing its representatives without a free press? And doesn’t free speech, by virtue of being free, offer protection against falsehood? Disproving falsehood requires more speech, not less. Benjamin Franklin Bache, the grandson of Benjamin Franklin and publisher of the foremost Republican newspaper, the Philadelphia Aurora, warned that the Sedition Act would “deprive us of the freedom of thinking, speaking and writing.”

Bache was no angel: with a knack for blistering journalism, he could happily attack Washington as avaricious and vain or represent Adams as “blind, bald, crippled and toothless.” He was such a thorn in the side of the Federalists that three weeks before the Sedition Act was passed, he was accused of seditious libel under English common law. Bache doubled down. While he waited for his hearing, he published a pamphlet reminding readers that a “free press is a most formidable engine to tyrants of every description.” To him, Adams was trying “to enlist this country on the side of despotism and then to pass alien, treason and sedition bills.”

Bache died during a yellow fever epidemic before his trial, but the fight was on. The Federalists had the upper hand: Federalist judges dominated the federal courts; Federalist marshals selected Federalist jurors. Pickering even went so far as to say that questioning the constitutionality of the Sedition Act was itself seditious. A rabid enforcer of the law whom even Adams would later call “bitter and malignant, ignorant and jesuitical,” Pickering directed the enforcement of the Alien and Sedition Acts with such perverse enthusiasm that, according to Bird, “Republicans found it unsurprising that he had been born in Salem, Massachusetts a half century after its witch trials.”

It was indeed a “reign of witches,” as Jefferson said in 1798. Among the prosecutions that Bird recounts are those against Thomas Greenleaf of The Argus, & Greenleaf’s New Daily Advertiser, a leading anti-Federalist newspaper and the only Jeffersonian one in New York City after the publisher of the Time Piece, John Daly Burk, fled the country, fearing prosecution. Vermont representative Matthew Lyon was the first person brought to trial under the Sedition Act. An outspoken Adams critic, Lyon served as his own attorney, arguing that the act was unconstitutional and therefore void. Associate Supreme Court Justice William Paterson would have none of it. After presiding over a biased and unfair trial, Paterson pronounced Lyon guilty, sentenced him to four months in prison, and fined him $1,000. Defending himself in his new newspaper, The Scourge of Aristocracy, Lyon arranged a lottery to help pay his fine—and was reelected to Congress while in jail.

Advertisement

But the Sedition Act didn’t just target newspapers and editors. When the very tipsy Luther Baldwin of New Jersey cried in a “loud voice” (according to the indictment) that President Adams “is a damned rascal and ought to have his arse kicked,” he was arrested for seditious speech. (He pled guilty and was fined $150 plus court costs.) When residents of Dedham, Massachusetts, raised a liberty pole criticizing the government, Federalists arrested Benjamin Fairbanks, a prominent local citizen. Claiming he didn’t know “how heinous an offense it was,” Fairbanks pled guilty and received a $5 fine and a sentence of six hours in jail. After a friend testified that Fairbanks had been under the influence of David Brown, an itinerant radical whom local Federalists considered a “wandering apostle of sedition,” Brown was arrested, found guilty, fined $400 plus court costs, and handed an eighteen-month prison sentence that stretched to more than two years since he couldn’t pay the fine or provide bond.

Although Bird alludes only indirectly to the influence of class in the sentencing of various defendants, economics was decidedly involved in the tax protest known as the Fries Rebellion, part of what Bird identifies as an “unrecognized second campaign” against the sedition law in early 1799. In northeastern Pennsylvania, residents strongly objected to federal tax collectors who came to measure their houses in order to collect the new property tax, though they were evidently protesting more than that, such as military expenditures, the creation of a standing army, and the Sedition Act.2 In March 1799, after seventeen men were arrested for obstructing the tax collectors—many had poured hot water on their heads—John Fries and anywhere from seventy to two hundred men, many of them armed, marched to Bethlehem, where the seventeen had been imprisoned. Fries demanded their release and local trial by a jury of their peers, not in Philadelphia. No one was hurt, and when ordered to disband, Fries and his men complied.

At first, President Adams dismissed the whole thing as “a silly Insurgence,” but silly or not, he sent troops to the region. Fries was arrested and convicted of treason, but when his attorneys discovered bias in one of the jurors, a new trial was ordered. Fries was convicted again and sentenced to be hanged. After Supreme Court Associate Justice Samuel Chase, who presided over Fries’s second trial, ruled that opposition to any law is treason, Fries’s lawyers walked out, leaving him without counsel. (No one comes off well during the trial, except perhaps Fries.)

Whether the Sedition Act was “connected to the Fries Rebellion,” as Bird alleges, may seem a stretch, but he demonstrates that six prosecutions connected with it involved seditious press or speech. That the Federalists were flexing their muscles—and were ordering troops to quell a nonevent—suggests to Bird that the army was at the beck and call of those Federalists who saw sedition around every corner. And though Adams would eventually pardon Fries, much to the disappointment of his cabinet, Bird also claims, with good reason, that the Federalists were expanding the criminalization of dissent.

In this they enjoyed the services of Chase, one of the most ruthless, biased, and arrogant enforcers of the Sedition Act. Appointed to the federal bench by Washington, Chase notoriously quashed whatever he considered an attack on the Adams administration. His rulings during the second Fries trial served as one of the articles of his eventual impeachment in 1804, as did his rulings during the trial of James Thomson Callender. Technically a Republican at the time, Callender was, however, known to sell himself to the highest bidder. Born in Scotland, he had fled England after publishing a scathing indictment of the British government. Around 1793 he landed in Philadelphia, where he peddled sensationalism with opportunistic panache, whether writing for the Federalist Philadelphia Gazette or secretly for the Republican Aurora. In 1797 he accused Alexander Hamilton of impropriety as secretary of the treasury, which forced Hamilton to admit his affair with a married woman; later Callender circulated the story of Jefferson’s affair with Sally Hemings.

By 1798 Callender was in Virginia and writing for the Richmond Examiner. Blasting Adams and his administration, he also published a volume called The Prospect Before Us, whose purpose was “to exhibit the multiplied corruptions of the Federal Government, and more especially the misconduct of the President,” particularly with reference to the Sedition Act. He said that Pickering belonged in a madhouse (this seems to have been a favorite insult) and that the tyrant Adams heaped on Americans “an American navy, a large standing army, an additional load of taxes, and despotism.” Chase would have none of that. He said Callender should be hanged.

According to Geoffrey Stone’s Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime, from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism (2004), the Callender trial was a national sensation. Chase demanded that the defense team submit to him the questions they planned to ask their witnesses and then denied them the right to present witness testimony. When one of Callender’s lawyers tried to argue that the Sedition Act violated the First Amendment, Chase told him that the jury was not competent to decide on the constitutionality of a law. Eventually, Callender’s lawyers quit, and he was found guilty. Chase fined him $200 as well as another $1,200 in surety bonds (his net worth), and sentenced him to nine months in prison, where he wrote a second volume of The Prospect Before Us, dubbing Chase a “detestable and detested rascal.” Jefferson later pardoned Callender, but the effect of the trial, said Madison, was that the Federalist Party “industriously co-operat[ed] in its own destruction.”

Even though some newspapers were shuttered and some editors were sentenced to prison or attacked physically, the number of Republican newspapers mushroomed, and even moderate Federalists began to lean Republican. What’s more, Jefferson and Madison both denounced the Alien and Sedition Acts in resolutions passed by the Virginia and Kentucky legislatures. The Kentucky resolution, secretly drafted by Jefferson in the fall of 1798, affirmed a sovereign state’s right to repel federal overreach. “Whensoever the General Government assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force,” Jefferson declared, inviting the other states likewise to pronounce the Alien and Sedition Acts unconstitutional. The argument unpleasantly foreshadows the ones made before and after the Civil War with respect to slavery and states’ rights; today it rebuts a chief executive who says that “when somebody’s the president of the United States, the authority is total.”

This is territory that Bird meticulously mapped in his previous book, Press and Speech Under Assault: The Early Supreme Court Justices, the Sedition Act of 1798, and the Campaign Against Dissent (2016). There, as well as in Criminal Dissent, he refutes the widely held assumption that no other states agreed with the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions, stressing that they weren’t “fringe” opinions but rather “positive milestones in forming an opposition party, and in establishing a strategy and an informal platform for the 1800 election.” Maryland, Delaware, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New York, New Hampshire, and Vermont did not reject the resolutions in their entirety; they simply said that the state wasn’t competent to declare a federal law unconstitutional. As for Tennessee and Georgia, they too didn’t fully oppose the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions. They actually urged the repeal of the Alien and Sedition Acts since they seemed “in several parts opposed to the constitution, and are impolitic, oppressive, and unnecessary.”

Jefferson’s Kentucky resolution has been interpreted as being more concerned with allocating power to the states than with free speech. But Madison’s “Virginia Report,” composed after he wrote the Virginia resolution, as if to explain it further, argued that freedom of the press is fundamental to the democratic process:

The right of electing the members of the government, constitutes more particularly the essence of a free and responsible government. The value and efficacy of this right, depends on the knowledge of the comparative merits and demerits of the candidates for public trust; and on the equal freedom, consequently, of examining and discussing these merits and demerits of the candidates respectively.

Representative Gallatin was blunter: “the true object” of the Alien and Sedition acts “is to enable one party to oppress the other.”

Though Bird holds extremists like Chase and Pickering largely (but not solely) accountable for the persecution of individuals and institutions under the Alien and Sedition Acts, he does not exonerate Adams. If historians have tried to whitewash his reputation, as Bird says, others certainly do not accept Adams’s later excuse that he had no part in the writing of the laws. After all, he did not veto them, as Bird notes. And though he signed only three deportation orders, he revoked official recognition of four diplomats—and more to the point, presided over a pervasive state of anxiety: noncitizens might be deported at any time, and a number of people left the US precisely to avoid arrest and expulsion. In fact, Bird’s scrupulous research doubles the number of Alien Act cases. None of them was brought to a conclusion because the federal government was busier with its sedition prosecutions, particularly before the election of 1800, and because Adams dispatched a new diplomatic mission to France, which quieted down certain Federalists.

But the laws were on the books, and the Federalists were responsible for them. Republicans were not blameless, but the Federalist commitment to criminalizing dissent chills the blood, especially today. Jefferson said it all: “I know not which mortifies me most, that I should fear to write what I think, or my country bear such a state of things.”

-

1

In 1918 the Alien Enemies Act was broadened to include women, and in 1941, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt revived it to allow for the registration, detention, or arrest of so-called enemy aliens from Japan and then Germany and Italy. ↩

-

2

Bird’s narration and analysis closely follows that of Paul Douglas Newman, Fries’s Rebellion: The Enduring Struggle for the American Revolution (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004). ↩