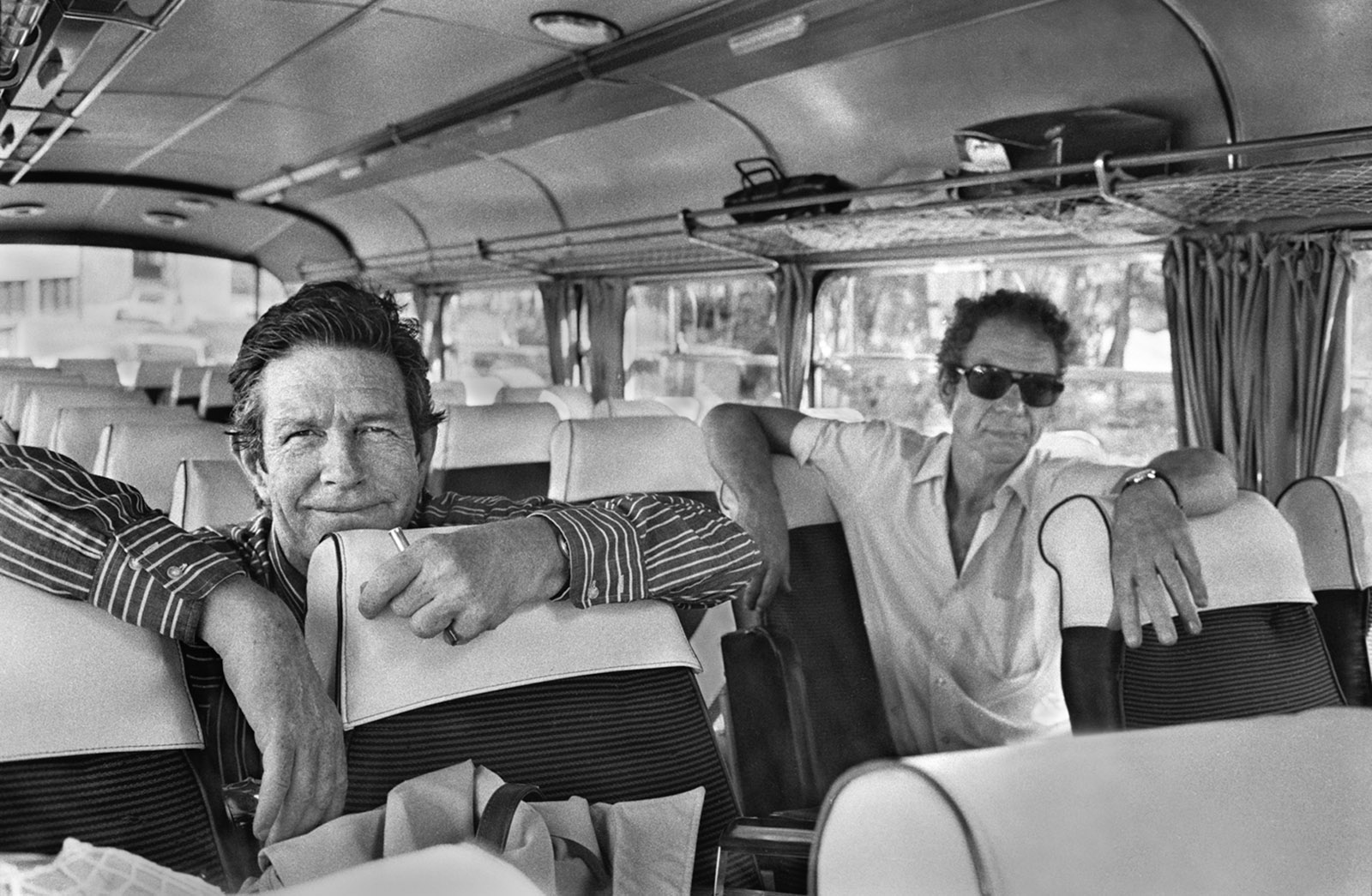

During the mid-1950s and early 1960s, Merce Cunningham, the most inventive and influential American choreographer of the second half of the twentieth century, took his dance company, founded in 1953 at the legendary Black Mountain College in rural North Carolina, on the road. They traveled in the maverick composer John Cage’s Volkswagen Microbus, that iconic conveyance of the counterculture. Cunningham was once asked why his company consisted of only nine people, including Cage, his artistic collaborator and life partner, and the painter Robert Rauschenberg, a former student of Cunningham’s at Black Mountain, who designed the sets and costumes. Cunningham responded that nine was the maximum number of people who could squeeze into the bus. On one occasion, stopping at a gas station in Ohio, the dancers, according to Cage, “all piled out to go to the toilets and exercise around the pumps.” Curious about the peculiar movements on display, the attendant asked if the dancers were a band of comedians. “No,” Cage answered, “we’re from New York.”

Encountering this anecdote in Cunningham, the exuberant recent film timed to coincide with the hundredth anniversary of Cunningham’s birth in 1919, you might find yourself wondering whether the gas station attendant was entirely wrong. There is a great deal of laughter in Cunningham, both on the screen and, during the two showings I attended, in the movie theater. Archival footage from the vaudevillian Antic Meet (1958) is laugh-out-loud funny. In the section titled “Room for Two,” a man with a Thonet chair strapped to his back courts a demure woman in an antique dressing gown, who appears from a door that rolls, seemingly on its own ghostly power, onto the stage. When the man kneels, she sits matter-of-factly on the chair. Everything in the pas de deux is performed deadpan, with an occasional discordant gesture, as when the man, in profile, lunges forward and opens his mouth wide, while the woman assumes a graceful arabesque.1 The score, one of Cage’s mashups of prepared piano and recorded noise, sounds like a machine shop, or a slowly moving freight train. Cunningham said Antic Meet was inspired by a line from Dostoevsky’s Ivan Karamazov: “Let me tell you that the absurd is only too necessary on earth.” It has a clearer lineage from Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton.

More a dance film than a traditional documentary, Cunningham showcases the choreographer’s work, in extended dance sequences, with minimal attention to chronology or biographical detail. Directed by the Boston-based documentarian Alla Kovgan, the film was available in some theaters in 3D, and opens with a swooping aerial view of Manhattan, which zooms in on an uncanny shot of seemingly tiny dancers in multicolored leotards slowly assuming balletic poses on a rooftop. Kovgan filmed, in vivid color, outdoor reenactments of classic Cunningham dances—in a forest, by a pond, in front of a castle—as though the dancers had escaped the confines of the theater altogether. These elegant, reverential sequences lack the urgency of the grainy, archival 2D footage of Cunningham himself, a stupendous dancer and magnetic stage presence, rehearsing his dancers or performing his own dances in his loose-limbed and seemingly improvisatory way.

Kovgan glosses over Cunningham’s early years: his upbringing in Centralia, Washington, in a family of lawyers, and his first meeting with Cage, another Westerner, at Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle, where Cunningham was an eager young actor, performing Shakespeare and Chekhov, as well as a dancer. Cage, seven years older, accompanied the dance classes with compositions partly indebted to the twelve-tone system of his teacher, Arnold Schoenberg, and partly to his own radical experiments with percussion. Cage would come to believe that Western music had taken a wrong turn with Beethoven, into expressiveness and heightened emotion; Beethoven’s “lamentable” influence, he felt, had been “deadening to the art of music.” Cage was married at the time, to an Alaskan artist of Russian background named Xenia. It isn’t clear when precisely the oddball composer and the preternaturally gifted dancer became romantically involved; Alastair Macaulay, dance critic for The New York Times, says they “became an item” in 1943. Cunningham remembered Cage, years later, as a formidable presence for the students, who referred to him as “the handsome new man in the red sweater.”

The pioneering choreographer Martha Graham, one of the founding figures of what came to be known, with its bare feet and bent torsos, as modern dance, saw Cunningham perform at a summer dance festival in California in 1939. She wasted no time in inviting the dazzling twenty-year-old to join her troupe. Kovgan’s film is oddly silent about Cunningham’s crucial years as a soloist in Graham’s company, from 1939 to 1945, in which he premiered roles like the revivalist preacher in Appalachian Spring, lording it over the cowering women of the congregation, or (as recorded in Barbara Morgan’s famous photograph) flying in from the wings as the spirit of March to inspire Emily Dickinson in Letter to the World.

Advertisement

For Kovgan, the real story begins with the formation of Cunningham’s company and the partnership with Cage and Rauschenberg. There is much hilarity in the film regarding the heroic early years, when the company seemed willing to try anything and audiences were predictably shocked. Dancers, who frequently donned their costumes and heard the musical score for the first time at dress rehearsal, or even opening night, were often surprised as well. But there’s a darker undertow, for much of the film, of privation: serious artists making do with no money, little food, no regular work, and scant understanding from audiences of what they were up to. “We only have two things in common,” Rauschenberg told Cunningham, “our ideas and our poverty.” When a tomato was thrown at the dancers, Cunningham ruefully remarked that he wished it had been an apple. “I was hungry.”

During the VW years, as Cunningham’s lead dancer Carolyn Brown referred to them in her vivid 2007 memoir, Chance and Circumstance, the company made a virtue of scarcity. Rauschenberg, who had driven the trash truck at Black Mountain, scavenged discarded furniture and distressed old clothes for sets and costumes. With no funds to rent theaters, Cunningham dispensed with the proscenium stage, developing a radically decentered choreography. The most extreme version, generously showcased in Cunningham, is Summerspace (1958), in which dancers twirl across the stage in ever more inventive and disorienting ways, encountering one another against Rauschenberg’s dizzyingly pointillistic backdrop. Random sounds foraged via tape recorder (a typical list from Cage: “The sound of a truck at fifty miles per hour. Static between stations. Rain.”) replaced paid accompanists. Even Cage’s famous “prepared piano” was the result of space constraints; with insufficient room for his beloved percussion instruments, he inserted stray objects among the piano strings to strike off unusual sounds.

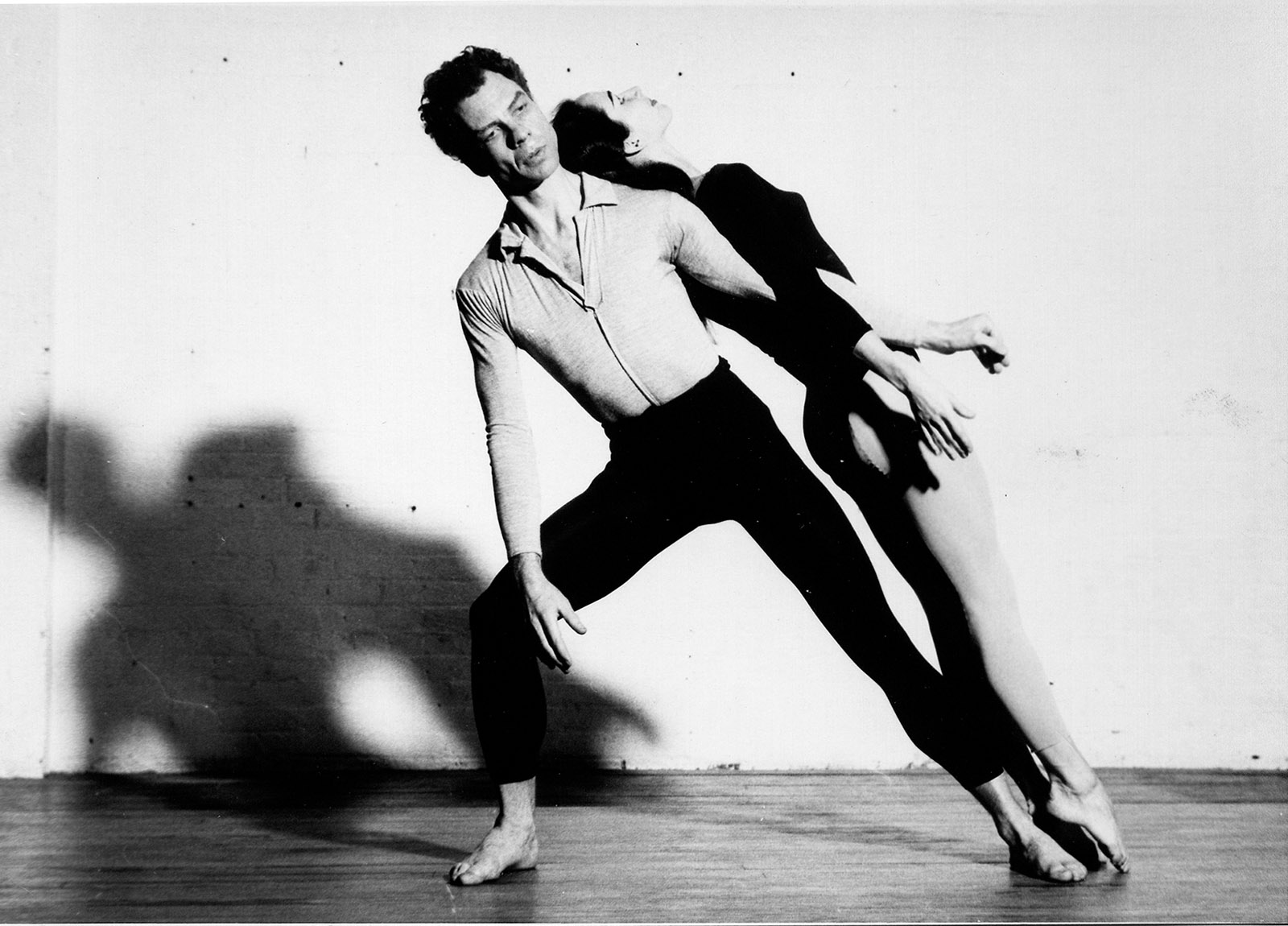

It is tempting to think that Cage’s love affair with noise found an analogue in Cunningham’s embrace of ordinary, everyday movement: walking (with feet parallel, not turned out as in ballet), running, crawling, clapping. But there is nothing ordinary about Cunningham in motion. Brown described her first impression of him dancing as “a strange, disturbing mixture of Greek god, panther, and madman.” We can see what she meant in 16mm film footage, which Kovgan discovered languishing in a German archive, of the astonishing seven-minute solo Changeling (1957).2 Roaming the stage in a ragged leotard and tight-fitting skullcap designed by Rauschenberg, Cunningham is a hybrid man-beast, with spasmodically twitching feet and flapping hands, discovering what his body can do. No one watching the dance, a ferocious update of Nijinsky’s L’Après-midi d’un faune, could think that its movements are borrowed from daily life—unless it’s the daily life of a wolf.

Modern dance was invented by women: Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis, Doris Humphrey, Martha Graham. But Merce Cunningham and Dance Company, as the troupe was known into the 1970s, was distinctly male influenced, not only by Cunningham and Cage, but also by a succession of artists—Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol—who collaborated with them. During the early years of the company, Cunningham gave himself the wilder, more jagged roles, as in Antic Meet and Changeling, while reserving tamer, more supportive parts for his female dancers. Even as late as the 1980s, the dance critic Arlene Croce thought the women in Cunningham’s company had “a quaintly well-bred collegiate look,” while the men, modeling themselves on Cunningham, were “untamed, impulsive, even feral.”

If Cunningham’s female dancers sometimes felt frustrated in being relegated to the more conventional roles, his refusal to explain what puzzling movements meant exacerbated their sense of exclusion. The dancer Marilyn Wood once had the temerity to ask, during a rehearsal of Antic Meet, whether Cunningham had “something particular in mind in these dances.” It was as though a taboo had been breached, as Brown recounts:

In the awful stillness that followed, the same thought raced through all our minds: had she really asked? We didn’t know whether to giggle or groan. As badly as we, too, might have wanted to know what he had in mind, we would never have presumed. The silence was excruciating. Merce sat motionless. After what seemed an interminable length of time (which was probably only a few seconds), Merce merely smiled benignly and said, “Yes.” Not another word.

There may have been an erotic element to these tensions. “Many of us dancers were somewhat in love with him,” company member Marianne Preger-Simon notes in her affecting new memoir, Dancing with Merce Cunningham, adding that they had “little comprehension of homosexuality.” Cunningham and Cage didn’t flout their intimacy; there were few same-sex duets in the dances, and the precise nature of their relationship wasn’t revealed until 1989. Recent critics have wondered whether Cunningham’s hermetic choreography reflected, in part, “a need to mask strong emotions in a homophobic environment,” as the scholar Carrie Noland puts it in Merce Cunningham: After the Arbitrary. But there also seems to have been an element of sexism depressingly familiar from other narratives of 1960s liberation, in which everyone was in on the joke except the women.

Advertisement

Readers expecting intimate revelations from John Cage’s Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) will be disappointed. The text, which Cage began writing in 1965, is very much a public document, parts of which Cage performed as lectures, with margins and section lengths determined by his beloved chance operations. As such, the diary can be seen as something of a sequel to his 1961 Silence, a compilation of idiosyncratic prose pieces that established Cage as an avant-garde writer as well as a composer. He had a cult following during the 1960s, when his fusion of Gertrude Stein and Zen Buddhism (both major influences) spoke to a generation impatient with the bromides of the Eisenhower years. Cage became known for enigmatic pronouncements such as “There is nothing to say and I am saying it.” During the Q&A following his original “Lecture on Nothing,” he insisted on giving “one of six previously prepared answers regardless of the question asked,” adding, “this was a reflection of my engagement in Zen.”3

The tone of the Diary is by turns hectoring and gnomic, with Cage’s gurus—Buckminster Fuller, Marshall McLuhan, and Marcel Duchamp—invoked on almost every page. Cage wants you to know that he and his enlightened friends have figured things out, if people would only listen to them. Some of his remarks seem startlingly prophetic. “We need for instance,” he proclaims in 1965, “an utterly wireless technology.” He worries, again presciently, that global communication won’t solve our problems. “Relevant information’s hard to come by,” he muses. “Soon it’ll be everywhere, unnoticed.” In 1967 he pictures people “getting home, plug[ging] in car: unused, it gets recharged.” We are reminded, several times, that Cage’s father was an inventor, concerned, among other things, with ecological degradation: “Dad’s dehydrator that worked electrostatically, separating refuse oil into dry chemicals, water that could be drunk, oil of the highest grade.”

Cage presents himself as something of an inventor as well, a tinkerer with ideas and attitudes. The chaotic layout of the book, and Cage’s insistent proclamation that “money is the root of all evil,” recall Ezra Pound, another relentless explainer. Cage can be funny on financial topics: “We ought either to get rid of God or to find Another Who doesn’t permit mention of trust in Him on pieces of money.” Or he can be merely opaque: “Fusing politics with economics prepared disappearance of both.” But there are also unsettling moments when a crude scorn for the clueless interrupts the anarchic frolic: “Utopia? Self-knowledge. Some will make it, with or without LSD. The others? Pray for acts of God, crises, power failures, no water to drink.”

For someone who insisted on the significance of ordinary experience, the urgency of “waking up to the very life we’re living,” Cage has surprisingly little to say in the diary about his own daily life, other than the joys of hunting mushrooms. Cunningham, with whom he shared that life, is barely mentioned. Again, one may feel that Cage and Cunningham, during the years before Stonewall, had every good reason to shroud their relationship. A cache of Cage’s letters, dating from 1942 to 1946, found among Cunningham’s belongings at the time of his death in 2009 and now published as Love, Icebox, would seem to promise what is missing from the Diary—namely, access to the most intimate regions of Cage’s emotional life. In these letters, Cage woos Cunningham by attacking his critics: “Nobody recognizes Nijinsky when they see him.” He lets down his emotional guard, with perhaps a whiff of Zen: “I say I’m unsentimental but I’m sitting at one of our tables and looking in a mirror where you often were.” The rain, “alternately terrific and gentle,” reminds Cage of his lover.

When Cage’s wife, Xenia, leaves him, in 1944, evidently aware of the growing intimacy between the two men, her departure prompts what Cage calls some “soul-searching.” “I did it once before,” he adds, “about 12 years ago. I’m not very good at it.” And when Cunningham, two years later, threatens to follow Xenia out the door, Cage panics. “I am worried that maybe you don’t love me and that you will love other misters,” he confesses.

I know you love me as artist friend and spirit but I am afraid that it is I who always forces sex; I am in erotic doubt—I know you love freedom. I don’t know how much I mean to you as sex or whether you simply tolerate me.

Scrawled across the bottom of the typewritten letter, Cage concludes, desperately, “I don’t know what else to say.”

It is tempting to think that here at last, in these impassioned, sexually explicit, and sometimes agonizing letters, is the real content, the sublimated Sturm und Drang, concealed beneath the emotionally cool surfaces of Cage’s music and Cunningham’s dances. “Love, Icebox,” the signoff of a playful letter from Cage adopting the persona of his refrigerator, would seem the perfect title for their passion under wraps. But the belief that raw emotion constitutes the real life while art is merely the disguise is a biographical fallacy. Fraught with sexual jealousy and fears of abandonment, Cage’s artless love letters could be anyone’s: generic, repetitious, and—it should be said—clearly not meant for us.

Besides, one could argue that hackneyed emotion was precisely what these two artists were trying to escape. The nature of that escape has been poorly understood, however. A generation of dance critics, following Cunningham’s lead, has asserted that his dances refer to nothing outside themselves, express nothing, mean nothing, are about nothing. “His dances are all about movement,” Jill Johnston wrote in The Village Voice in 1963, “and what you see in them that relates to your common experience is your own business and not his.” For critics raised on Frank Stella’s Cagean quip that “what you see is what you see,” this view of Cunningham has seemed, for half a century, final, inarguable. At the outset of Cunningham, the choreographer tells us, slowly and emphatically, that his dances do not “refer.”

And yet it has been perfectly obvious to discerning critics, to audiences, and to his own dancers that Cunningham was a marvelously expressive dancer, and that his dances are full of dramatic interest and incident. “From the start,” as the great dance critic Edwin Denby wrote in 1968, “Merce was an extraordinary dramatic dancer with a very special and very large dramatic imagination.” What had counted as dramatic in modern dance was what Cunningham had experienced in Martha Graham’s company for six long years: the grand emotional turmoil of her heroines, with their stereotyped gestures of “contraction and release.”4 In one of his letters, Cage writes with distaste of Graham’s “heights of frustration greatness.”

What a relief to escape from all that. Still, the release wasn’t into some region of “pure movement” but into a different, less stereotyped realm of emotion. As Denby put it with his usual precision, “I have felt that by avoiding the drama out of which Martha Graham made her pieces, [Cunningham] discovered lyric aspects of dance that were much lighter than any that were discovered by people who were closer to Martha.” In Merce Cunningham: After the Arbitrary, Noland explores how Cunningham’s dances do, after all, engage human emotion. His various practices, worked out with Cage—composing music and choreography separately, determining the order of sequences by chance, eliminating clear narratives—might seem to be aimed at suppressing meaning, an explicit goal of Cage’s aesthetics. According to Noland, however, Cunningham sought “not to deny relationality but to extend it; he does so by interrupting the momentum of our habitual trajectory so that other, less prescribed encounters might occur.” The reason Cunningham resisted Graham’s “emotional explanations” for dances was not because he wanted to dispense with emotion, but because he felt that her directives tended to “stiffen” movement, as the dancers sought to reproduce her feelings rather than honoring their own.

Dancers are not tubes of paint or cello strings. They are not windup toys. They have distinctive character traits and physical oddities. Cunningham particularly relished what company member Viola Farber refers to, in Kovgan’s film, as “our flaws.” According to Preger-Simon, Cunningham “would deliberately let us find our own way of replicating his combinations,” a process that “allowed our individual way of moving to emerge.” When he was commissioned to teach Summerspace to members of the New York City Ballet in 1966, he realized, working with George Balanchine’s impeccably trained corps, how much his own choreography depended on idiosyncratic dancers interacting fully and freely with one another, as fellow human beings, and not as mere precision instruments of the choreographer’s vision. “I asked them,” he said of the City Ballet dancers, “to look at people, not ‘stage right.’”

-

1

In Merce Cunningham: After the Arbitrary, Carrie Noland traces the pose to the Odious Warrior figure of classical Hindu drama, one of Cunningham’s unacknowledged sources. ↩

-

2

Hilarie M. Sheets, “Long-Lost Merce Cunningham Work Is Reconstructed in Boston,” The New York Times, June 18, 2015. The footage from Changeling was a centerpiece of the 2015 traveling exhibition on the arts at Black Mountain College, “Leap Before You Look.” See my review in these pages, “A Wonderfully Ephemeral College,” May 26, 2016. ↩

-

3

It was also a reflection of his engagement with Stein. “At Pomona College, in response to questions about the Lake Poets, I wrote in the manner of Gertrude Stein, irrelevantly and repetitiously. I got an A. The second time I did it I was failed.” See Silence (Wesleyan University Press, 1961), p. ix. ↩

-

4

When I studied at the American Dance Festival at Connecticut College, during the summer of 1972, Graham technique was still dominant while Graham herself, confined to a wheelchair, was a regal presence. ↩