Carson McCullers, who once loomed large in the mid-twentieth-century literature of the South, now seems the smallest bird on the branch that holds William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Welty, Truman Capote, Richard Wright, and McCullers’s close friend Tennessee Williams. Her precocious talent survived her turbulent marriage, her fragile health, and her drinking (she carried a thermos of spiked tea to her desk each morning), but her pace slowed. Two disabling strokes when she was thirty almost ended her career. Many surgeries followed. It took McCullers over ten years to complete her final novel, Clock Without Hands (1961). She died six years later at fifty. “She was a tragic figure in a way,” recalled Edward Albee, “but she was very, very good at being a tragic figure. I think that amused her, too, in part.”

Loneliness, isolation, and obsessive love: McCullers never buried her central themes. “Certainly I have always felt alone,” she wrote in a preface to one of her plays. A connoisseur of yearning, attuned to its quirks and variations, she realized that love itself—the subjective experience of love—is so transporting that, for some, the longed-for mutual connection can be almost beside the point. Her own great loves—always women—tended not to return her devotion: “I live with the people I create and it has always made my essential loneliness less keen,” she added.

The passionate oddballs in her fiction fasten almost randomly on others. In her debut, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (1940), four Georgia townspeople cling to a polite deaf-mute jewelry repairman named John Singer, about whom they know almost nothing. One at a time, they visit his boarding house room and talk at him for hours, resenting the occasional overlap in visitors. His silence is no impediment; in fact, it helps. Their sense of intimacy with Singer sustains their private dreams. The town’s black physician, Doctor Copeland, for instance, burns with purpose—his mission is no less than the moral and intellectual awakening of his race in the South—while thirteen-year-old Mick, whose family struggles for every dime, listens outside her neighbors’ windows at night until their radios go silent, plotting her career as a composer. Singer’s visitors consider him their one friend—the ideal listener—while Singer himself pines for his deaf-mute companion, Antonapoulos, who cannot sign or read:

Sometimes he thought of Antonapoulos with awe and self- abasement, sometimes with pride—always with love unchecked by criticism, freed of will. When he dreamed at night the face of his friend was always before him, massive and gentle. And in his waking thoughts they were eternally united.

If Antonapoulos loved him back, this would not be a Carson McCullers novel. Severely limited emotionally and intellectually (McCullers never spells out his disabilities), Antonapoulos has eyes only for booze and sweets.

When The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter appeared in June 1940, McCullers, just twenty-three, was hailed as the new Steinbeck, among other accolades—a superficial comparison, but the first at hand, since The Grapes of Wrath (1939) had just won the Pulitzer Prize. The compassion Steinbeck brought to poor, exploited farmworkers McCullers brought to small-town southerners of limited prospects, white and black. Her characters build castles in the air but end up behind the costume-jewelry counter at Woolworth’s. The methodical shutting down of dreams at the close of a McCullers novel reinforces the constraints her characters face—they are bound by convention, by poverty, by race and gender, by illness or deformity, by the closet. When Mick drops out of school on impulse to work full-time, she feels “mad all the time…. But the store hadn’t asked her to take the job. So there was nothing to be mad at. It was like she was cheated. Only nobody had cheated her.”

Southern writers shared an “approach to life and suffering” with the Russian realists, McCullers argued in a 1941 essay. “In both old Russia and the South up to the present time a dominant characteristic was the cheapness of human life.” Hence her “cruelty” in delivering these harsh reckonings for characters she has invited us to love. But her overriding attribute is her empathy. There is no Other in her best work, no one beyond the reach of her affection or her playful jabs. Richard Wright gave The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter the review of a lifetime in The New Republic, remarking on the “astonishing humanity that enables a white writer, for the first time in Southern fiction, to handle Negro characters with as much ease and justice as those of her own race.”

Although her position in the canon has slipped, McCullers still attracts devotees. The acceptance she offers the freaks and misfits in her novels, her lovelorn loners, can be consoling. “Reading her was a sort of literary déjà vu,” recalls Carlos Dews, the doyen of McCullers studies, who edited her memoir, Illumination and Night Glare (1999) and is now working on an edition of her letters. Dews discovered her novels as an undergraduate in Texas:

Advertisement

I felt a common sense of experience—growing up queer in the South, feeling from my earliest moments of consciousness a sense of isolation from those around me, a sense of antipathy to the place I was born…and perhaps strongest of all, a profound sense of loneliness.

The latest votary is Jenn Shapland, whose spare but impassioned memoir, My Autobiography of Carson McCullers, traces her archival discoveries about McCullers and her growing identification with the author—in light of Shapland’s hard-won self-acceptance of her own lesbianism and of her chronic disability due to a congenital heart condition. Her stimulating book is part fan letter, part detective story, and part steely corrective to the influence of the guardians of McCullers’s estate and others who wanted to normalize her, the “retroactive closeting by peers and biographers.”

Quoting Janet Malcolm’s famous analogy of the biographer to a “professional burglar…triumphantly bearing his loot away,” Shapland posits memoir as “a voyeurism of the self”:

I am perched outside my own windows as I try to see into Carson’s. Her house has been broken into, ransacked by looters. What am I looking for? What do they—the other biographers, critics, contemporaries—obscure from view?

In 2012, during a graduate internship at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, Shapland came across eight letters to McCullers from Annemarie Clarac-Schwarzenbach, a Swiss writer and photographer. Although known to McCullers scholars and biographers for decades, these documents from 1941–1942 had not trickled into the literary mainstream. When Shapland opened folder 29.1, she realized she was reading love letters—or letters that seemed to allude to past love, to a relationship that Clarac-Schwarzenbach had ended by returning to Europe from New York. She described her wartime travels in Congo as a journalist for the Free French, her warm memories of McCullers, her idea of translating McCullers’s second novel, Reflections in a Golden Eye (which McCullers had dedicated to her), into German; but McCullers’s replies were missing. “Immediately, without articulating a reason,” Shapland writes, “I wanted to know everything about them both.”

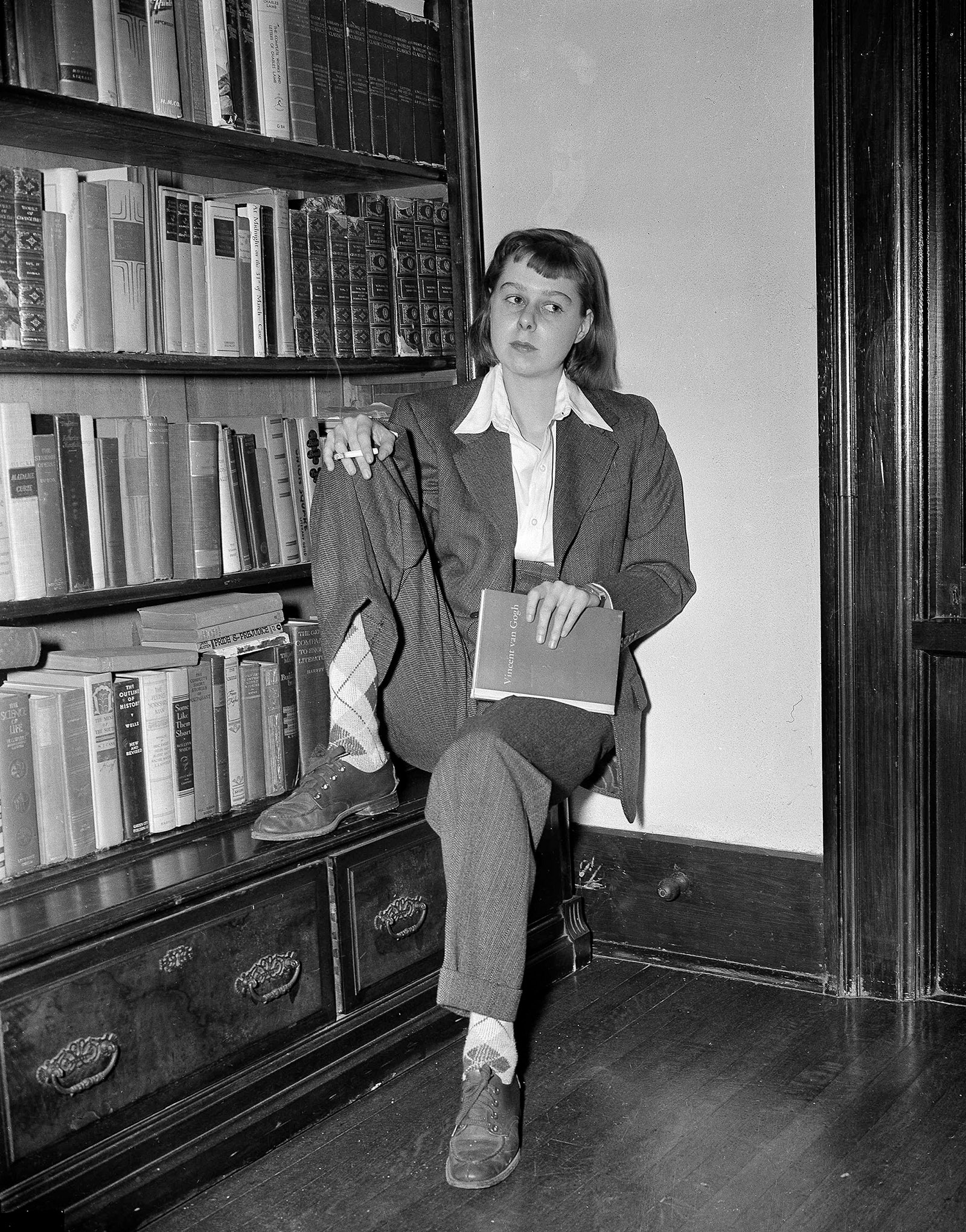

Lula Carson Smith was born in Columbus, Georgia, in 1917, the adored eldest child of a watch repairman, Lamar Smith, and his dreamy, idealistic wife, Marguerite Waters Smith, who declared her child a genius while she was still in utero. By age six, Lula Carson’s gift for the piano emerged. Soon after, she began to write plays for her siblings. At thirteen, she dropped “Lula” from her name.

Carson’s piano studies set her apart, when she might otherwise have been only a tall, unpopular tomboy with a jarring fashion sense. (Decades later, classmates remembered her over-long skirts and her “ugly white knee socks…when the rest of us wore stockings or short crew socks.”) Her mother indulged her. They smoked together on the porch when she was just fourteen. She was clearly resisting the march toward southern womanhood. At fifteen she suffered her first serious illness—undiagnosed rheumatic fever, which led to a lifetime of frailty and strokes. But during her long convalescence, she discovered books.

Her family later thought that, of all McCullers’s fictional characters, she most resembled Frankie Addams, “the vulnerable, exasperating, and endearing” adolescent in The Member of the Wedding (1946),1 who fell in love with her brother’s bride and with a dream of belonging—“you are the we of me,” Frankie longed to tell the couple. Her masterpiece—and her most subtle treatment of race in the South—The Member of the Wedding shows McCullers in full control of her lavish, sometimes unwieldy gifts, including her humor, her sympathetic understanding of children, and her unusual evenhandedness. (The reader wants to throttle Frankie for her selfishness and monomania, while identifying with her every impulse.) When she was thirteen, her world revolved around her new piano teacher, Mary Tucker, a concert pianist whose husband was assigned to command the Infantry School at nearby Fort Benning. She spent her weekends with the Tuckers, and their eventual move away felt like a heartless abandonment. But through Mary Tucker, Carson met Edwin Peacock, a young gay man besotted with music and ideas, who was also stationed at the fort in the Civilian Conservation Corps. “My only friend,” she called him. They remained close for life. From that point on, as Shapland notes, she was most comfortable with queer friendships.

Carson fled the South for New York after high school—supporting herself with odd jobs and eventually taking night classes at Columbia and studying creative writing at New York University—but she was isolated and ill and came home often to recuperate. On one of these visits, Peacock introduced a new friend, Reeves McCullers, an army clerk from Fort Benning who joined their musical parties and political arguments, and wanted to be a famous writer. “It was a shock, the shock of pure beauty, when I first saw him; he was the best looking man I had ever seen,” she wrote in her memoir. “I was eighteen years old, and this was my first love.” The couple married two years later, in September 1937, and moved to North Carolina. They would both write, they decided, trading off years: one at the typewriter, the other at a paying job.

Advertisement

That this young love went disastrously wrong is among the first things one is likely to learn about Carson McCullers. They both drank recklessly, and the marriage was already strained when they moved back to New York in June 1940, shortly after The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter appeared. Reeves’s literary ambitions collapsed in front of a typewriter—no evidence survives of anything he may have written, beyond letters—while McCullers basked in her brilliant reviews.

Suddenly famous, she found herself among new friends, including wartime refugees from Europe like Klaus and Erika Mann. She stayed out late, leaving Reeves alone in their fifth-floor Greenwich Village walkup, and through Erika Mann she met the bewitching, drug-addicted Annemarie Clarac-Schwarzenbach, who was soon all she could think about. That fall, she accepted her friend George Davis’s invitation to move (without Reeves) to a sort of artists’ collective in a large Victorian house in Brooklyn, where she lived with W.H. Auden, Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Paul Bowles, among others, pooling expenses and sharing meals.2 Auden collected the money and kept order, as best he could. But the McCullerses kept rekindling their bad romance until 1953, when Reeves killed himself in France with an overdose of sleeping pills, having failed to convince (or coerce) Carson to commit suicide together.

“To tell another person’s story, a writer must make that person some version of herself, must find a way to inhabit her,” Shapland writes. Her book is not about McCullers’s writing or even, strictly speaking, about McCullers herself as she can be reconstructed in the historical record. Rather, it “takes place in the fluid distance between the writer and her subject, in the fashioning of a self, in all its permutations, on the page.”3 McCullers serves as a mirror for Shapland, who even begins to perceive physical resemblances between them. Ultimately, “I wanted…a rendering of my own becoming. A love story I could believe.” That love story was not Carson and Reeves.

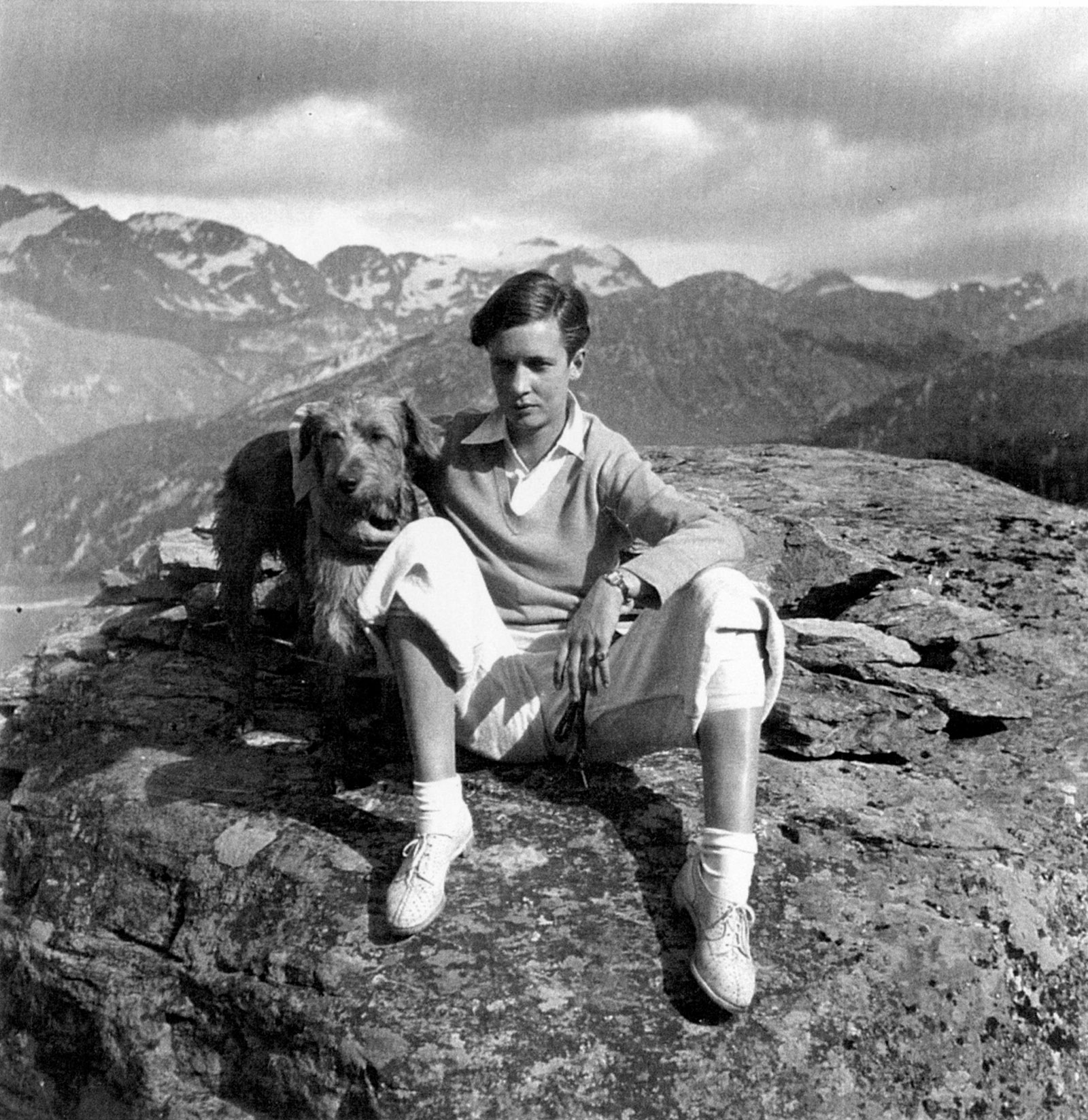

In some ways, Annemarie Clarac-Schwarzenbach resembled the young Reeves McCullers—androgynous good looks, volatility, heavy boozing, and a penchant for dramatic scenes. Thomas Mann called her a “ravaged angel.” The blue-eyed, cropped-haired Clarac-Schwarzenbach, a silk heiress on the outs with her abusive, Nazi-sympathizing mother, was “a known lady-killer,” as Shapland puts it. She was also an adventurer; in 1939, with Europe on the brink of war, she traveled from Geneva to Kabul in an open car with another woman writer. She wrote over three hundred articles before her accidental death in late 1942 from an act of bravado: riding her bicycle without hands over steep, stony ground. McCullers wrote in her memoir, “She had a face that I knew would haunt me to the end of my life.”

When they met in June 1940—the same month Carson and Reeves returned to New York—Annemarie confided that she had just quit drugs. “You don’t know what it means to be cured of this terrible habit,” she told Carson. “I asked her how long it had been since she’d given up morphine and she answered, ‘today.’”4 Despite intense talks, their attraction did not develop along the lines Carson had hoped. Instead, she became another of Annemarie’s helpers, and once considered supplying her drugs.

The Ransom Center holds forty-eight boxes of papers purchased from the McCullers estate after her death. (McCullers had at one time promised she would donate them to her hometown public library in Columbus if it desegregated, but the administration refused.) With these documents came a sometimes puzzling assortment of personal effects that remained boxed and more or less neglected until Shapland photographed and cataloged them. Here was the vest McCullers wore for a portrait session with Cecil Beaton and the pastel-colored nightgowns she eventually wore all day at her last home, in Nyack, New York, and also a pair of cream wool cable-knit socks, lightly soiled. These items can now be viewed on the Ransom Center’s website; a close-up of the sock stains is offered.

Archivists call such items “realia,” a term drawn from education, where it means objects from everyday life brought into a classroom to help students grasp another culture or the past. Touching an adored writer’s belongings offers a heady illusion of intimacy and a shared sensory experience. Each sign of wear, Shapland writes, is “a communication from its wearer in a previous life”: “The clothes are a kind of hinge or portal to the author’s body, to her self and her self-representation.”

What these clothes cannot describe is the closet they came from. McCullers did not exactly hide behind her marriage—many writers who knew her at Bread Loaf or Yaddo in the early 1940s remembered her obsession with Annemarie—but she was selective in disclosure, and her estate has remained so, presumably out of discomfort with her same-sex desires and liaisons. McCullers also suffered a professional setback in 1941 with her radically frank and fairly explicit gay-themed second novel. Having courted readers with the tenderness of her debut, she flung the dark, unfunny Reflections in a Golden Eye at them only a year later. Here, her lonely characters also fail to connect, but the outcome is savage. So were reviews. Although she continued to explore gender and same-sex attraction in her fiction, she never returned to the icy narrative voice of Reflections or to that degree of sexual detail.

In the mid-1960s, McCullers’s first (and authorized) biographer, Oliver Evans, published a sanitized version of her life, based in part on interviews at her Nyack home, where she had moved permanently in 1953. Annemarie comes up twice in the book, as her “favourite of them all” from the old days. This is as candid as McCullers could be, given the period and her need to protect those close to her.5 A decade later, after her death, Virginia Spencer Carr’s The Lonely Hunter revealed the train wreck of the McCullerses’ marriage in salacious detail, including Carson’s pursuit of women. The McCullers estate, getting wind of Carr’s ingenuity as a researcher, had begged people not to talk to her. They also barred her from citing any unpublished material from the Ransom archive.

The third and most recent full-length biography was Josyane Savigneau’s Carson McCullers: A Life (2001), translated from the French by Joan E. Howard, and essentially a remix of the Carr biography—warmer, as Savigneau intended, but much, much straighter. As Terry Castle wrote in The Apparitional Lesbian (1993), her classic study of lesbianism in modern culture, “Virtually every distinguished woman suspected of homosexuality has had her biography sanitized at one point or another in the interest of order and public safety.” Protective of “her Carson” (to borrow Shapland’s concept), Savigneau would sooner see McCullers with no mature sex drive at all than as a lesbian or bisexual. McCullers’s crushes on women were “adolescent and quite bothersome…. Her romantic obsessions show little or no evidence of sexual desire. Rather, they reveal a wish to love in a kind of troubadourish manner.” Indignant at the “partisans of homosexuality” trying to queer McCullers, as she saw it, Savigneau stands on a lonely battlement, firing at an absurd preponderance of evidence.

Savigneau offers a hetero-corrective to Carr, while Shapland rebukes them both for “trying to explain away the obvious.” But Shapland has slightly oversold her thesis about the closeting of McCullers. Scholars and critics have been exploring the queer elements of McCullers’s work and even referring to her as lesbian or bisexual or trans or gender nonconforming for decades—often with less “evidence” than is now available. Only in her bibliography does Shapland mention Sarah Schulman, for instance, a prominent lesbian writer whose multigenre exploration of McCullers—essays, a play, a projected novel, and an as yet unrealized film—spans twenty years.6 Similarly, although Shapland visited McCullers’s childhood home in Georgia, fondling her possessions and breathing her air, she avoided meeting anyone who had known her and who might offer competing impressions: “None of these is my Carson.”

In 1958 McCullers began treatment for depression with Dr. Mary Mercer, a Nyack child psychiatrist. At crucial points in Shapland’s memoir, she paraphrases typed transcripts of Dictaphone recordings made by mutual agreement during these therapeutic sessions, before McCullers and Mercer ended their professional relationship and became the most important people in each other’s lives. These transcripts became available to scholars in 2014, when Mercer’s executor shipped her personal McCullers archive in two filing cabinets to the Carson McCullers Center at Columbus State University in Georgia. Before that, Mercer had insisted the transcripts were part of McCullers’s confidential psychiatric records and fought McCullers’s siblings successfully for their return from the Ransom archive.

Patchy and occasionally hard to follow, the transcripts cover much the same territory as McCullers’s later essay “The Flowering Dream: Notes on Writing,” and the unfinished autobiography she dictated shortly before her death. But unlike these statements, they bring McCullers’s sexuality into sharp focus. In the transcripts, McCullers recounts the full misery of loving Annemarie, who was in love with someone else and suffering mental breakdowns, complicated by cycles of addiction and withdrawal.

In November 1940, five months after they met, Carson heard that Annemarie had escaped from a psychiatric hospital. She leapt from her sickbed in Columbus (Carson had gone South, as usual, to recuperate from a winter illness) and rushed to New York, where she found Annemarie holed up at a mutual friend’s apartment in Manhattan, knocking back gin. Finally, under these fraught conditions, Annemarie invited Carson to undress and began to touch her: “And I felt this flowering jazz passion, you know, and I felt I had her. I thought at last, I had Annemarie, at last, at last.” But drug-sick and on the verge of psychosis, Annemarie abruptly kicked Carson out of bed for being too thin and insisted she bring her Gypsy Rose Lee instead.7

Shapland’s memoir includes an author’s note on the copyright constraints that compelled her to paraphrase important passages like the one above (I have quoted from another source) rather than quoting from the transcripts directly. Her publisher, Tin House, declined to expand on these conditions when asked about them. One is left to assume that the McCullers estate—which allowed Carlos Dews to quote at length from the therapy transcript in a 2016 essay8—took against Shapland’s project. Sadly, these limitations mar the book and contribute, at times, to an airless quality, a sense that we are rattling around in Shapland’s head with “her Carson.”

In her will, McCullers divided her estate equally among her two siblings and Mary Mercer. After McCullers’s death, her sister, Margarita, sorted and sold most of McCullers’s papers to the highest bidder, the Ransom Center, where Shapland read them.

“What is placed in or left out of the archives is a political act,” the writer Carmen Maria Machado has remarked on the documenting of queer lives.9 It can also be an emotional one, as it clearly was for Mary Mercer, who died in 2013. In the late 1960s she had fought the McCullers Estate for the return of many papers besides the transcripts that she considered private, and she consistently declined to help biographers, except for one brief meeting with Josyane Savigneau, who described Mercer as “elegant—and intimidating.” Mercer would not allow Savigneau to record their conversation or even take notes. “All [Carson] had was a mad desire to stay alive,” Mercer told her. “To live and to write. To live in order to write.” After McCullers’s death, Mercer bought her Nyack home at 131 South Broadway from the other executors and rented the rooms to artists.

The love Mercer would not discuss in her lifetime—“withholding is a means of possession,” as Shapland astutely observes—she allows scholars to discover and interpret now: all the cards, for instance, from over fifty bouquets of flowers McCullers sent her.

Shapland may not have read Mercer’s book, The Art of Becoming Human (1997), which is another way to know this lovely, guarded woman. A fairly conventional psychoanalytic account of child development (complete with penis envy), it opens into a commentary on the stages of adult life, leading toward a peroration on ideal, unselfish love. Mercer quotes McCullers heavily throughout—alongside Shakespeare and Goethe—and echoes several of her main themes. She clearly lived inside McCullers’s imaginative world after the writer’s death and kept talking with her. She urges readers not to broadcast their good fortune in love: “It is best to guard the source of private joy from thievish ears.” In a section on divorce, she includes an excerpt from one of her own unfinished poems, spinning off from McCullers’s formulation of the “we of me” in The Member of the Wedding. The poem, however, also speaks to a different grief:

There comes an end to passion

When the shadow of our death drifts off into space.

Oh, take back me from we

Oh, take back me from we

There has to be a me to ever love again.

-

1

The description is from Margarita Smith’s introduction to The Mortgaged Heart: Selected Writings. ↩

-

2

The house, 7 Middagh Street (torn down in 1945 to make way for the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway), became known as “February House” after Anaïs Nin noticed on a visit how many residents had been born in that month. See Sherill Tippins, February House (Houghton Mifflin, 2005). ↩

-

3

Compare McCullers’s remark in “The Flowering Dream: Notes on Writing” (Esquire, December 1959) that she became the characters she wrote about: “When I write about Captain Penderton, I become a homosexual man; when I write about a deaf mute, I become dumb during the time of the story. I become the characters I write about and I bless the Latin poet Terence who said, ‘Nothing human is alien to me.’” ↩

-

4

Soon after they met, Clarac-Schwarzenbach wrote a piece on McCullers, translated by Padraig Rooney and published in Agni, No. 84 (2016). See also Rooney, The Gilded Chalet: Off-piste in Literary Switzerland (Nicolas Brealey, 2016). ↩

-

5

In 1960 McCullers’s close friend Newton Arvin (Truman Capote’s former partner) had been forced out of a thirty-eight-year teaching career at Smith College for getting muscle magazines in the mail. This likely served as an example, close to home, of the cost of exposure. ↩

-

6

Films about McCullers have been oddly difficult to complete. The late music producer Dan Griffin, a McCullers fan, filmed several priceless interviews with friends and family, including Edward Albee and John Ziegler, Edwin Peacock’s long-term partner, and with related figures like Virginia Spencer Carr, in the hope of making a documentary. He posted clips on YouTube, where they can still be seen. ↩

-

7

In the chronology of Dews’s edition of the Library of America volume of McCullers’s Stories, Plays, and Other Writings (2017), he quotes a 1940 letter from Clarac-Schwarzenbach to Klaus Mann while McCullers was away at Bread Loaf: “I thought I had acted with all due caution and had treated her gently, but she is waiting for me to arrive from one day to the next, convinced that I am her destiny.” ↩

-

8

Carlos Dews, “‘Impromptu Journal of My Heart’: Carson McCullers’s Therapeutic Recordings, April–May 1958,” in Carson McCullers in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Alison Graham-Bertolini and Casey Kayser (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). ↩

-

9

Carmen Maria Machado, In the Dream House (Graywolf, 2019). ↩