Once a week in the spring of 1994 I would bicycle over to a brownstone on West 16th Street to see a man named Sam Chwat in his ground-floor office. He called himself a speech coach, and a large part of his business was to train actors who had been cast as Prospero, say, or Creon, so that they did not sound as if they came from the Bronx or Akron, Ohio. But I was not an actor seeking help with a role. I was seeing Sam for something else, something a bit apart from the other speech-related services he offered. A friend who had sought him out for help with public speaking had recommended him to a lawyer who was representing me in a lawsuit. Ten years earlier I had published a two-part article in The New Yorker about a disturbance in an obscure corner of the psychoanalytic world whose chief subject, a man named Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, hadn’t liked his portrayal and claimed that I had libeled him by inventing the quotations on which it was largely based. So he sued me and the magazine and the Knopf publishing company, which had brought out the article as a book called In the Freud Archives.

In an afterword to a subsequent book, The Journalist and the Murderer (1990), I wrote about the lawsuit, taking a very high tone. I put myself above the fray; I looked at things from a glacial distance. My aim wasn’t to persuade anyone of my innocence. It was to show off what a good writer I was. Reading the piece now, I am full of admiration for its irony and detachment—and appalled by the stupidity of the approach. Of course I should have tried to prove my innocence. But I was part of the culture of The New Yorker of the old days—the days of William Shawn’s editorship—when the world outside the wonderful academy we happy few inhabited existed only for us to delight and instruct, never to stoop to persuade or influence in our favor. As the Masson case wound its way through the courts—dismissed at first, then reinstated, and eventually brought to trial—the press-watching public became increasingly pleased by the spectacle of the arrogant magazine brought low by the behavior of one of its staff writers. While Masson gave over two hundred accusatory interviews, I—in dogged accord with the magazine’s stance of unrelenting hauteur—said nothing in my defense. Nothing at all. Nothing of course produces nothing, except further confirmation of guilt.

But it was at trial that the influence of The New Yorker proved to be most dire. There was a style of self-presentation cultivated at the magazine that most if not all staff writers had adopted and found congenial. The idea was to be reticent, self-deprecating, and, maybe, here and there, funny, but to always keep a low profile, in contrast to the rather high one of the persona in which we wrote. I remember my shock at meeting A.J. Liebling for the first time. I had been reading him for years and imagined him as the suave, handsome, brilliantly articulate man of the world that the “I” of the pieces portrayed. The short, fat, boorishly silent man I met was his opposite. I came to know Liebling and to love him. But it took a while to penetrate the disguise of innate and magazine-induced unpretentiousness in which he made his way through the world as he wrote his wonderful pieces narrated by an impossibly cool narrator.

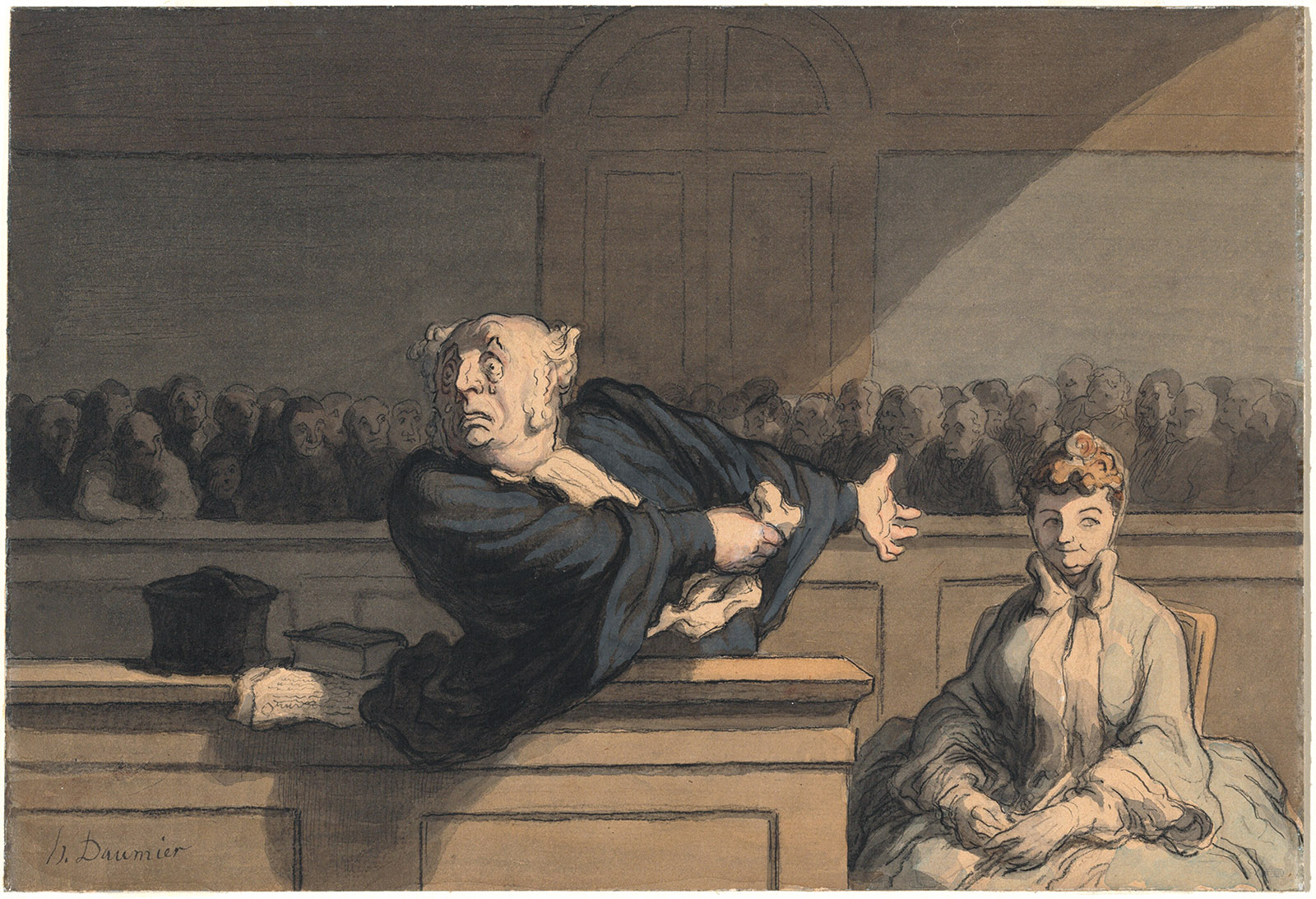

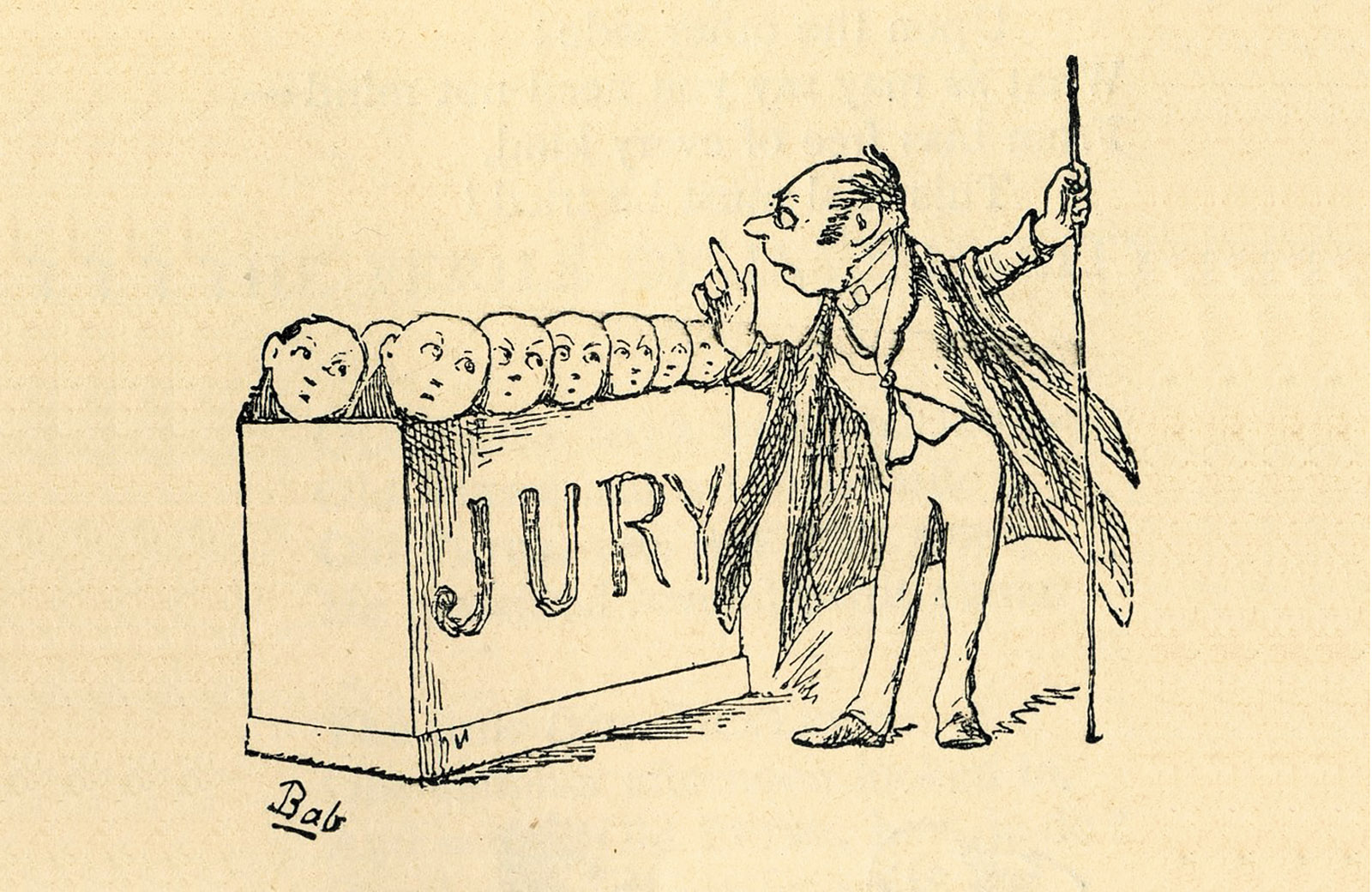

When I took the stand at the trial in San Francisco in 1993 I could not have done worse than to present myself in the accustomed New Yorker manner. Reticence, self-deprecation, and wit are the last things a jury wants to see in a witness. Charles Morgan, Masson’s clever and experienced lawyer, could hardly believe his good fortune. He made mincemeat of me. I fell into every one of his traps. I came across as arrogant, truculent, and incompetent. I was at once above it all and utterly crushed by it. My lawyer, Gary Bostwick, succeeded in inflicting some damage on Masson—he portrayed him as boastful and sex-crazed—but it was not enough to offset the damage I had helped Morgan inflict on me. The jury agreed with the plaintiff’s accusation that five quotations in my article were false and libelous. A jubilant Masson had only to wait for the jury’s final determination of how many millions of dollars in damages he would collect from me.* (The New Yorker itself was cleared of the charge of “reckless disregard” required for a finding of libel; Knopf had extricated itself from the case years earlier.)

Advertisement

Then the gods played one of their little reversal-of-fortune pranks. The jurors came back from their deliberations with the news that they were deadlocked. They could not agree on the amount of damages. Some thought Masson should be awarded millions of dollars. Others thought he should collect nothing. One juror thought he should collect one dollar. The judge could not move them and was obliged to declare a mistrial and to schedule a new trial. I had suffered an ignominious defeat, but I had been given a second chance to prove my innocence. Whew!

Not many of us get second chances. When we blow it, our fantasies of how we could have done it right remain fantasies. But the fantasy had become a reality for me, and I was determined not to waste the incredible good fortune that had come my way. My visits to Sam Chwat were part of the half-year of preparation for the second trial, almost like a military campaign, to which Bostwick and I devoted ourselves. Sam was the Professor Higgins who would transform me from the defensive loser I had been in the first trial to the serene winner I would be (and was!) in the second one.

The transformation had two parts. The first was the erasure of the New Yorker image of the writer as a person who does not go around showing off how great and special he or she is. No! A trial jury is like an audience at a play that wants to be entertained. Witnesses, like stage actors, have to play to that audience if their performances are to be convincing. At the first trial I had been scarcely aware of the jury. When Morgan questioned me, I responded to him alone. Sam Chwat immediately corrected my misconception of whom to address: the jury, only the jury. As Morgan had been using me to communicate to the jury, I would need to learn how to use him to do the same.

There were some minor but not unimportant particulars Sam inserted into this new concept of myself as a guileful performer. I would need to dress differently. At the first trial I wore what I normally did when out of my work uniform of blue jeans, namely skirts or trousers and jackets in black or subdued colors, clothes that looked nice but didn’t draw attention to themselves. The idea was to be tasteful. Another No! The idea was to give the jurors the feeling that I wanted to please them, the way you want to please your hosts at a dinner party by dressing up. This would be achieved by a “menu,” as Sam called it, of pastel-colored dresses and suits, silk stockings and high heels, and an array of pretty scarves. The jurors would feel respected as well as aesthetically refreshed, the way they do by women commentators on TV who wear colorful clothes of endless variety. I did as Sam advised, and after the announcement of the verdict, when Bostwick and I went to speak with the jurors, they made a point of commenting on my clothes. They said that each day they looked forward to seeing what I would wear next, especially which scarf I would wear.

There was a seemingly small but all-important technical problem that, for a while, neither Sam nor I could solve. The witness stand was located midway between the interrogating attorney’s lectern on my right and the jury stand on my left. How was I supposed to perform for the jurors when I had to turn my back on them while being questioned? The answer came to me one day in a flash. I would position my chair so that it partially faced the jury. Thus, when Morgan questioned me I could reply over my shoulder, while remaining frontally connected to the jurors.

The second and most crucial part of the second-chance work was to make me faster on my feet under cross-examination, in fulfillment of the fantasy of saying what I should have said in the first trial instead of what I did say. Bostwick assumed that Morgan would repeat the questions that had served him so well, and he and I devised answers to them that brought l’esprit de l’escalier to a new level. At trial, Morgan did not disappoint us. He confidently asked the old questions and didn’t know what hit him when I produced my nimble new formulations. I remember one of the most satisfying moments. At the first trial Morgan had repeatedly tortured and humiliated me with the question: “He didn’t say that at Chez Panisse, did he?” I had wiggled and squirmed. Now I could answer him with crushing confidence.

I need to give the reader some history here. In the early months of the (ten-year-long) lawsuit, Masson claimed that he had said almost none of the things he was quoted as saying in the article. When a transcript of my tape-recorded interviews was made, it showed that he had said just about all the things he denied saying. But five quotations remained that were not on tape. They were:

Advertisement

(1) “Maresfield Gardens would have been a center of scholarship, but it would also have been a place of sex, women, fun.”

(2) “I was like an intellectual gigolo—you get your pleasure from him, but you don’t take him out in public.”

(3) “[Analysts] will want me back, they will say that Masson is a great scholar, a major analyst—after Freud, he’s the greatest analyst who ever lived.”

(4) “I don’t know why I put it in.”

(5) “Well, he had the wrong man.”

I had lost the handwritten notes that would have been enough to prove the genuineness of the first three—the most incendiary—quotations; I had only typewritten versions, which did not meet the standard of proof. Thus, under our nervously accommodating legal system, Masson had the right to a trial by jury. As it turned out, two years after the second trial, the lost notes were found at my country house, in a notebook that my two-year-old granddaughter pulled out of a bookcase, attracted by its bright color. It had all been for nothing.

Meanwhile, however, as Masson’s day in court approached, he and Morgan had a problem to solve: how to fill the time of the trial. The five quotations—fatuous as they may have made Masson appear—were surely not compelling enough to justify making eight men and women sit on hard chairs for four weeks and decide whether or not to award him millions of dollars. A portrait of me as a malevolent woman out to destroy the reputation of a naively trusting man needed to be fleshed out by other crimes than the one of five lines of misquotation. They hit on the crime of “compression” as a leading one.

Their opportunity arose from an incident in 1984, when an article appeared on the front page of The Wall Street Journal written by a young woman named Joanne Lipman, who had graduated from Yale the year before and was hired by the Journal a few months later. The article was about the liberties that the writer Alastair Reid took in reportage from abroad he had been publishing in The New Yorker since 1951. Reid, born in Scotland, was primarily a poet and translator, notably of Jorge Luis Borges, and also known for having seriously irked Robert Graves by stealing one of his White Goddess girlfriends. Lipman first encountered Reid in her student days at Yale, where she heard him speak at an extracurricular seminar and was struck by the unconventional way he said he practiced journalism. After starting at the Journal, she called Reid and conducted a series of interviews with him in which he unrepentantly elaborated on these practices, which the newspaper considered horrible enough to put on its front page as evidence of the fraud The New Yorker had been perpetrating on readers of its “prestigious pages.”

Reid happily babbled to Lipman about the things he had made up in his reports from Spain. He had pieced together several people he knew into a composite character. He had set a scene in a bar that had closed years earlier. He had invented conversations. As an unacknowledged legislator, he felt bound to go beyond what the non-poet journalists among us do. Lipman wrote, “‘The implication that fact is precious isn’t important,’ Mr. Reid says. ‘Some people (at the New Yorker) write very factually. I don’t write that way…. Facts are only a part of reality.’” Lipman also interviewed Shawn, who tried to say that of course The New Yorker is as factual as it is possible to be while not saying that Reid ought to be drawn and quartered.

Lipman’s story created a scandal in the journalistic world, one that was deeply enjoyable for those who did not work at The New Yorker and mortifying for those who did. I remember feeling mad at Reid for opening his big mouth and talking about what we do in our workshops. I assumed that he strayed further from factuality than the rest of us ever imagined or were even capable of doing, but I also knew that some New Yorker writers—the great Joseph Mitchell, for example—quietly used techniques that resembled some of those that Reid preened himself on using. Mitchell had suffered some embarrassment when a character he called Mr. Flood was outed as a composite.

The Alastair Reid affair fell neatly into Morgan’s hands as a solution to the problem of how to fill the time at his disposal to make me look bad. Although I hardly shared Reid’s contempt for factuality, I had unapologetically, almost unthinkingly, used a literary device in In the Freud Archives that was commonplace at The New Yorker but that outside journalists—in the accusatory atmosphere following the Lipman article—saw as another violation of the reader’s good faith. The device was the uninterrupted monologue in which characters made preposterously long speeches in impossibly good English. Anyone could see that the speech had never taken place as such but was a compilation of what the character had said to the reporter over a period of time. Not everyone liked the convention, but no one thought it was deceptive, since its artificiality was so blatant.

I set my long monologue with Masson at the restaurant Chez Panisse in Berkeley, where he and I ate lunch on the first day of my interviews with him. During the lunch he excitedly spoke of the events that had catapulted him from an impressive and well-paid position as director of the Freud Archives to his present condition of jobless humiliation and indignation. He spoke wildly and not always coherently. Over the next six months I spoke with him dozens of times on the phone and a few times in person, and was able to fill in the gaps of his account and, further, to inspire formulations that ever more imaginatively expressed his sense of having been wronged. I then wrote my monologue. It was like making a collage. It never occurred to me that I was doing anything wrong by using scraps that had been acquired at different times.

But Morgan’s “He didn’t say that at Chez Panisse, did he?” question, with its implication that the reader was being deceived, was hard to answer. During our period of preparation for the second trial, Bostwick, Chwat, and I spent a great deal of time on it. Finally, an answer evolved from our efforts that I still recall the pleasure of delivering on the stand. It took the form of a long speech about the monologue technique that Morgan kept interrupting but was unable to stop. I went relentlessly on and on. I talked about the difference between the full and compelling account of his rise and fall in the Freud Archives that Masson gives in the article and his wandering incomplete speech in the restaurant. I spoke of the months of interviews out of which, bit by bit, the monologue was formed. I concluded by saying, “I have taken this round-about way of answering your question, Mr. Morgan, because I wanted the jury to know how I work, and what we’re talking about here in talking about this monologue.” “Mrs. Malcolm, you will be given all the chances in the world to tell this jury how you work, so don’t worry about it” was Morgan’s lame riposte. I didn’t worry. I had already gleefully seized my opportunity. When Bostwick and I interviewed the jury after its verdict and asked them what they thought of the monologue technique, they said they saw nothing wrong with it. They said they understood that writers had artistic obligations.

At the second trial Bostwick improved his own performance as Masson’s antagonist. In his best moments, he played him like a matador playing a bull. Under Bostwick’s punishing interrogation, Masson seemed pathetic, as he never was in my article. I almost felt sorry for him.

Sam Chwat died of lymphoma in 2011 at the age of fifty-seven. I was shocked and saddened by the news. I remember my sessions with him with undiminished gratitude and pleasure. He was a straightforward, modest, kind person, with a fine, interesting mind. His unspoken but evident distaste for the New Yorker posture of indifference to what others think and his gentle correction of my self-presentation at trial from unprepossessing sullenness to appealing persuasiveness took me to unexpected places of self-knowledge and knowledge of life. After the trial, I had no further occasion to appear in public and did not seek any. I relapsed into my usual habits of solitary work and private intimacy. Looking back on my life as a writer I don’t regret the trade-off of the openly performative for the less obvious way writers draw attention to themselves. My memories of the time in my life when I went on stage and performed like a trouper seem somewhat unreal now. But my rehearsals with the man who had briefly made me into one remain wonderfully vivid.

This Issue

September 24, 2020

Ball Don’t Lie

Making Order of the Breakdown

-

*

I say “me,” but it would have been The New Yorker’s insurance company that made the actual payment. All my legal fees, travel expenses, hotels, and meals were paid by this open-handed company. Sam Chwat’s services were included. ↩