In the summer of 1982, as a young oncologist at the University of California at Los Angeles, I developed a hacking cough, fever, and loss of appetite. After a few weeks the symptoms did not abate, and I contacted my internist, who ordered a chest X-ray and blood tests. The X-ray showed a patchy pneumonia, and the blood tests an inflamed liver. I underwent more extensive testing, but no diagnosis could be made. I feared that I had AIDS.

The disorder had been reported to the CDC a year earlier by a UCLA colleague, Dr. Michael Gottlieb. He described five previously healthy homosexual men who had contracted pneumocystis pneumonia. (The pneumocystis carinii microbe was known to afflict severely malnourished children and immune-compromised patients, such as those recovering from organ transplants.) Not long after Gottlieb’s communication, a dermatologist at New York University named Alvin Friedman-Kien reported to the CDC an “outbreak” among gay men in New York City and California of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a skin tumor that had been observed endemically in Central Africa and sporadically among elderly Ashkenazi Jewish and Mediterranean males. Clinicians began to diagnose more and more gay men with aggressive lymphoma—scores, then hundreds of once healthy, mostly young patients with cancers or infections and severely impaired immune defenses.

Because I specialized in oncology and had conducted research on viruses targeting immune cells, I began to care for AIDS patients. No one knew then what caused these patients’ immune deficiency. Although the disorder appeared to be transmitted sexually, the routes of contagion were not fully defined. I did not believe myself to be at risk other than in my role as a physician at the bedside, but there I had ample exposure to patients who coughed, sweated, and even bled; early on, we took scant precautions. I was terrified that I would be the first doctor to contract AIDS in the course of routine care.

My terror was based on what I had seen the disorder do to these young men. With impaired immune defenses, virtually every organ system in the body was attacked and devastated by opportunistic microbes. Patients suffocated from pneumocystis pneumonia. They experienced explosive seizures from fungal infections of the brain, uncontrollable diarrhea from parasitic infections of the bowels, and unrelenting fevers from tuberculosis-like organisms typically carried by birds. Those with Kaposi’s sarcoma developed bulbous red-and-purple tumors that distorted their faces, choked their throats, and swelled their limbs. Lymphoma often grew throughout the central nervous system, causing paralysis. AIDS was a horror.

After several weeks of further testing, a diagnosis was finally made: I had contracted a microbe called mycoplasma that causes pneumonia and, rarely, hepatitis. I was treated with antibiotics and my condition slowly improved. But as I returned to work caring for numerous men, and soon some women, with AIDS, the terror that I myself had the disorder remained. I had nightmares that mycoplasma was a misdiagnosis, that I was writhing in agony in a bed on our AIDS ward, next to the patients I had seen on rounds.

In 1983 the cause of AIDS was identified as a retrovirus ultimately called HIV, and soon thereafter tests were developed to accurately diagnose those infected. I spent an anxious few days waiting for my result, trying to block from my mind the possibility that I carried the virus and that my life would end in a spiral of suffering. The HIV test was negative. It took some time to fully relinquish the haunting fear.

We are now in the midst of the Covid pandemic, and Dr. Ross Slotten’s memoir of caring for AIDS patients in Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s, The Plague Years, could not be more timely. Slotten himself feared that he would succumb to the condition; as a gay man whose first long-term lover fell ill with the disorder and could well have transmitted it to him, he had a clear risk of contracting HIV. In his book he articulates the struggle that all caregivers experience to sustain emotional equilibrium while discharging their duties, all the more so today, with health care workers putting themselves at risk of COV-2. In Boston alone there are more than one thousand such workers—not only doctors, but nurses and EMTs, as well as transport, cleaning, and administrative staff—who have contracted COV-2.

Slotten studied classics at Stanford as an undergraduate, and then medicine at Northwestern, aiming to serve the elderly, homeless, and indigent:

In 1984 I opened a practice with Tom K., who’d completed his training in family medicine at St. Joe’s three years before I did. Our office was in a nondescript building…on the north side of Chicago, on the margins of two historic neighborhoods: Old Town, once the haunt of artists, writers, intellectuals, and other eccentrics; and Cabrini Green, one of the most notorious housing projects in the nation, overrun by gangs but also home to hardworking people who had trouble finding affordable housing because of their race and low income.

With the advent of AIDS, he and Tom K., also a gay man, quickly became leading figures in combatting the epidemic in Chicago, learning as they went along: pneumocystis pneumonia was optimally treated with trimethoprim-sulfa, esophageal candidiasis with ketoconazole, and Kaposi’s sarcoma with interferon-a or low doses of vinblastine, a chemotherapy drug derived from the periwinkle plant.

Advertisement

San Francisco and New York City have long been cast as the epicenters of the AIDS epidemic, but Slotten provides a history of another major urban center coming to grips with an illness that was unexpected and misunderstood. He vividly explores the powerful pull of denial that enabled the virus to spread within Chicago’s gay community. Despite the creeping anxiety, Slotten writes, the back rooms of gay bars still offered venues for anonymous sex performed without precautions, as if in defiance of the reports from the coasts of growing numbers of deaths. Sex was part of the gay community’s emerging self-affirming culture, Slotten notes, so public health measures to protect against the disorder were too often seen as punitive rather than salubrious:

No one wanted to admit that AIDS was transmitted through sex….

But as new cases of AIDS were reported nationwide, public health officials urged gay men everywhere to start using condoms, even when having oral sex…. After struggling so hard to gain acceptance, gay men were being told to give up what they’d been fighting for, the freedom to love whom they desired. Hadn’t many straight people ignored religious dictates to abstain from sex until after marriage?…

Despite the surge in cases reported nationwide, there were still fewer than two thousand at the end of 1982 and only a handful of them were in Illinois, a number that didn’t impress me. Lacking a firm grounding in the mathematics of epidemics, I wasn’t as alarmed as I should have been, especially since it hadn’t been absolutely proved that the cause was infectious. The virus that caused it wasn’t identified for more than another year…. Like many other young gay men, I remained in a state of denial about my risk.

Slotten kept a journal throughout his decades of clinical practice, and in Plague Years he draws on his notes to revisit the time when there were no antiviral medications to combat HIV and restore immune defenses. These only appeared in the 1990s with the development of a succession of agents—first AZT, then DDI, and then the HIV protease inhibitors—that were sufficiently potent to block the virus and allow the body to recover some degree of immunity. The former were based on older cancer drugs, the latter entirely novel agents designed via analysis of the crystal structure of the HIV enzyme.

Slotten does not spare the reader the physical anguish he witnessed at the bedside during AIDS’s early years:

Steve…suffered during the last few months from intractable diarrhea, advancing Kaposi’s sarcoma, CMV retinitis, and neuropathy—one devastating AIDS-related problem after another. His lover Sean confided to me that at home he exploded in fits of rage, which upset Sean and their roommate Heather. On a previous admission he’d groaned all night, his nurse Rita had reported, but he told me that he was “all right.” I knew he wasn’t. Should he give up or go on? he asked at every visit. He wanted to do both but couldn’t decide.

Before becoming ill, he had worked as an artistic director at an advertising firm. He had been a handsome, tall, lanky white man. Now a beaklike nose jutted out from a gaunt face. His eyes sank into their sockets, and when he slept they remained half open like those of a corpse. Patches of hair were all that remained of his once luxuriant mane. When healthy, he had been self-conscious about his psoriasis, which spared his face but erupted in red scaly plaques on his torso, extremities, and penis. As he became more immune suppressed, his psoriasis had all but disappeared, for reasons I couldn’t explain. What replaced the psoriasis was far worse. He had the papery tan skin of a mummy. In fact, his whole lower body was mummified. Kaposi’s sarcoma had turned his legs into purple-brown carapaces and bloated his feet like those of a dead body floating in a river.

Different doctors took different approaches to dealing with the emotional toll of caring for the mostly young and dying. I was trained as a specialist in blood diseases and cancer, and learned not to flee from fatal maladies like leukemia, glioblastoma, and metastatic melanoma. Even so, there were moments I felt overwhelmed by the misery of it all. I was fortunate to be able to leave the bedside for my laboratory, and find respite working to combat HIV away from the people it was killing, testing numerous antiviral agents—some of which succeeded as effective therapies while others did not—and experimental drugs against Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Advertisement

In the 1990s I began writing, not a journal, but a book that memorialized some of the patients I had cared for, seeking to depict their struggle in the face of familial rejection and social stigma.1 Nevertheless, I still felt what Slotten highlights: a sense of uncertainty in my role as an effective physician. As a doctor of family medicine, Slotten, much like the physicians caring for Covid patients today, had not expected to encounter relentless death. He is unflinching in examining his own psychology, the mechanisms he erected to protect himself, articulating his sense of deficiency in a bracing confessional tone:

In 1992…I had the dubious distinction of having signed more death certificates in the city of Chicago—and by inference the entire state of Illinois—than any other physician. How many deaths had I witnessed; how many more could I withstand before breaking down?…

Sometimes I wondered what kept me from throwing myself off the precipice, either literally or figuratively. Perhaps it was my idealistic sense of duty and refusal to abandon my community during its darkest hour; or the adrenaline rush I experienced from being at the forefront of a new field of medicine, which exaggerated my importance in my own eyes and the eyes of my patients and colleagues; or the instinctive drive for self-preservation, which prevented me from having a nervous breakdown or, worse, committing suicide; or simply inertia, because maintaining the status quo, terrible as it was, seemed less frightening to me than change, such as pursuing a different career in medicine. Questioning motives sows doubt; doubt leads to indecision; and indecision to inaction, the worst possible response to a crisis, especially for a doctor. So I simply did not question my motives.

Slotten describes how he retreated into a cold numbness, unable to summon tears even for those he knew well, similar to responses now being reported among frontline Covid caregivers. He was able to sustain his emotional detachment for months, but then he would be overcome with a desire for physical escape. He left Chicago for trips to faraway countries like Namibia, and to places filled with aesthetic treasures like Northern Italy:

Despite the Jewish guilt—a concept my mother didn’t believe in—I could continue practicing medicine only if I interrupted my working life at strategic intervals when my spirit flagged. A cliché like “Life is short” became a mantra of survival. Delaying gratification until some imaginary retirement date seemed absurd to me, when so many men my age were dying decades before their time. I didn’t want to look back on my life with regret, cursing myself for putting off the dreams I could have pursued in my prime. Although I was HIV-negative, I behaved like someone who walked through the valley of the shadow of death, not fearless but fearful that the end was near, that the moments of good health were precious and shouldn’t be wasted.

Only with these periodic escapes from Chicago could he find respite and be able to return to face the daily devastation of AIDS.

No one in modern times was prepared for a pandemic like Covid that has reached across the globe and affected all demographics.2 Not since the great influenza pandemic of 1918 have doctors and nurses faced a contagious disease that so broadly threatens themselves, their families, and their communities, and from which there is currently no physical or psychological escape like Slotten’s, by traveling to safe places. In my own case, sheltering at home and social distancing block the release I once found with extended family and friends, the hypnotic laps at Harvard’s Blodgett pool, and the solace at synagogue when I listened to the Kaddish and whispered the names of the patients I had cared for and lost to AIDS. Houses of worship are now incubators of Covid. Gyms and pools are closed to limit spread of the virus.

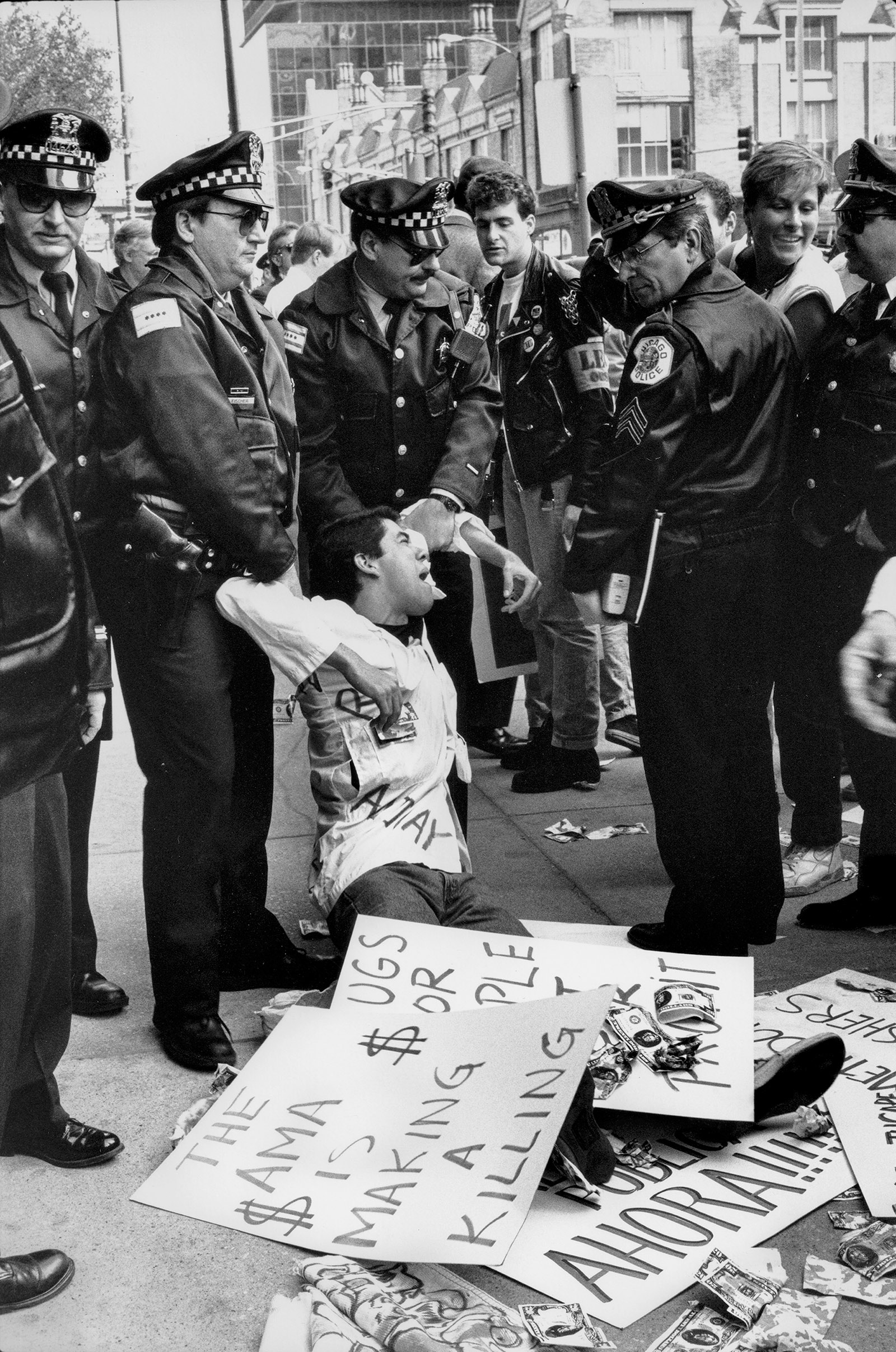

Science ultimately stemmed the AIDS epidemic. Following the discovery of the virus in 1983, each of its genes was characterized, and antiviral drugs were developed to disrupt the pathogen’s inner machinery. At first, as Slotten documents, the gay community was suspicious of the scientific establishment, just as the scientific establishment dismissed the tactics and radicalism of the gay community. But even the most vitriolic and confrontational critics, like Larry Kramer of ACT UP,3 eventually wore down and won over government scientists like Dr. Anthony Fauci; they and their communities became partners in seeking medications that would meaningfully benefit the afflicted with the least side effects. What became known as HAART—highly active antiretroviral therapy, often called the “antiviral cocktail” combining nucleoside inhibitors like AZT and 3TC with protease inhibitors like ritonavir and later integrase inhibitors—now has been formulated as a few, or even a single, pill for many patients, taken once a day. At the end of The Plague Years, Slotten celebrates this considerable change: the death rate among AIDS patients in the US has fallen dramatically. There are still areas of the nation, like the South and minority communities, where rates of HIV infection, along with other sexually transmitted diseases like syphilis, continue to rise. But Slotten, in Chicago, with access to effective therapies, tells a young man who recently was infected with HIV, without hesitation, that there is much life ahead:

It had been almost a decade since I’d cared for someone with advanced HIV infection, and I hadn’t lost a patient to AIDS since 2004. Once a master of the art of HIV medicine in the era before HAART, I’d almost forgotten how to treat opportunistic infections. Now I would need the internet to guide me. In 2016 most of my patients with HIV were vigorous and healthy, their virus kept in check by powerful medications.

Slotten writes insightfully on the pernicious effects of being gay during the AIDS epidemic, of the shame and stigma he internalized. But he notes that AIDS contributed to advancing the civil rights of gay people in the United States and many countries abroad. As Slotten emphasizes, the disease made it impossible for gay men to stay in the closet. They had to seek care, and in many cases reveal their sexuality to their employers and their families.

Yes, there were still those who viciously characterized AIDS as divine punishment for the sin of same-sex love. But these voices were increasingly marginalized by popular Hollywood celebrities and fashion icons, and then charitable organizations that recruited donors from the traditional corridors of the establishment, like banking and retail. Politicians—notably Joe Biden, who influenced Barack Obama—stepped forward to advocate for gay rights, and the military soon became more tolerant. Ultimately, federal and local legislation and Supreme Court rulings made discrimination against gay people illegal:

So much had changed, and not only in how we managed HIV infection. Although 1984 had looked nothing like George Orwell’s dystopia, 2014 looked nothing like 1984, at least in terms of American society’s perceptions of the LGBT community. Even the term LBGT (or later LGBTQ) had no resonance in 1984. At that time we belonged to the caste of untouchables. Thirty years later more than half the country supported same-sex marriage. It’s not a stretch to claim that without AIDS, same-sex marriage might not have come to pass as soon as it did. By bringing so many well-known, talented, and influential people out of the closet, AIDS paradoxically humanized gays and lesbians. AIDS didn’t accomplish this feat alone, but it was an instrumental factor, especially after it ceased to threaten mainstream America and was transformed by the miracle of modern medicine into a chronic and manageable infection.

Slotten married Ted Grady in Chicago in June 2014, six days after Illinois legalized same-sex marriage. The inner turmoil that he carried before coming out to his family was ultimately resolved with the unexpected loving acceptance of his mother.

The marriage, as for many gay couples, followed a civil union some three years earlier, which Slotten’s mother “attended happily.” She confided to her son, “I really like your mother-in-law,” and did simple but unambiguous things to indicate her support, like refusing to eat at Chick-fil-A because its COO was opposed to LGBTQ rights, and sending a birthday card to Ted with an “Equality Forever” stamp on the envelope.

The Plague Years prompts us to draw comparisons between AIDS and the current Covid pandemic. COV-2 contagion is not restricted to sex, blood, and needles like HIV, but is largely spread through the air and via droplets. There is still denial of the severity of the virus, but it is promoted not within the afflicted communities but by conspiracy theorists and those with political agendas. While a productive détente was ultimately forged between activists who realized the grim reality of HIV and dedicated scientists and clinicians, there is scant evidence that such a bold alliance will be seriously and consistently sustained by the Trump administration and its most vocal supporters. Fauci, for one, has become a target not only of vicious conspiracy theorists but of Trump and the White House Office of Communications, and instead of the focused and organized efforts of the federal government that followed the initial laxity of the Reagan administration to address HIV, there is still no coherent nationwide plan of consequence to tackle Covid—rather, there’s chaos and scattershot measures.

What loudly echoes from Slotten’s account is the commitment of caregivers to confront the uncertainty of a contagious disease. The applause at 7 PM in many cities for their efforts against COV-2 has largely waned. What persists across the country is the tragic burden of such dedicated care, as in the case of Lorna Breen, the emergency room physician at NewYork-Presbyterian Allen Hospital who committed suicide, apparently overwhelmed after she herself became infected with COV-2. The longer-term effects on the mental and physical health of these doctors and nurses are yet to be seen.4 Slotten, for one, seems to have lost a part of his psyche needed to mourn:

Over the years death has obsessed me, and increasingly as I grow older and continue to ponder the purposelessness of life. We come, make our brief mark on the world, and vanish—that’s a cliché but a simple truth. So many lives lost to AIDS, I thought, a surfeit of grief that almost negated my ability to experience grief at all.

I hope this is not the long-term outcome of the Covid pandemic, but such emotional hollowing is understandable after years witnessing disease and loss in the clinical trenches.

There is a terrible fear that the toll on health care workers from Covid will have been in vain if Trump’s failure to effectively tackle the pandemic continues, if testing is not ramped up to levels that allow for identification of carriers and contact tracing, if distribution of protective equipment is not done rationally but rather through nepotism and profiteering, if experts are removed from important positions after questioning incompetent political leadership, and if reopening the economy is done haphazardly to fulfill talking points on cable TV in hopes of gaining reelection.

Perhaps the greatest lesson we can take from the AIDS epidemic is one that came after the movie star Rock Hudson died, effectively removing the blinders that President Reagan was wearing. Reagan, a friend of Hudson, at last ceded authority to scientists like Fauci, who knew how to speak to the public about illness and create a sense of common cause, and to mobilize both the public and private sectors to triumph over a virus that had never been seen before and many believed could not be effectively combated. AIDS arrived as a murderer; now it can be shackled. We are nowhere near that point with Covid-19.

This Issue

September 24, 2020

Ball Don’t Lie

A Second Chance

Making Order of the Breakdown

-

1

The Measure of Our Days: New Beginnings at Life’s End (Viking, 1997). ↩

-

2

Covid has affected primarily the elderly, but also many middle-aged and some young people; disproportionally African-American and Hispanic populations in urban areas on the coasts; and now those in red states, including Native American and some Caucasian residents, particularly those with comorbidities like obesity and diabetes. Essential workers often belong to the most vulnerable populations. ↩

-

3

Kramer, a vocal critic of federal corruption and incompetence in confronting Covid, died on May 27, 2020. ↩

-

4

See Jan Hoffman, “I Can’t Turn My Brain Off: PTSD and Burnout Threaten Medical Workers,” The New York Times, May 16, 2020. ↩