Sitting at home this summer, quarantined with my paper, my pen, and my anxieties, I dipped into Lynda Barry’s latest you-can-do-it-too book, Making Comics. It seemed the perfect tonic—part doodle, part manual, part therapy. Trouble was, Barry’s exercises soon awakened a couple of my latent anxieties—Devwahrphobia (fear of homework) and Atelodemiourgiopapyrophobia (fear of imperfect creative activity on paper)—which almost made me shut the book. But then it dawned on me that Barry’s genius—yes, she is certified, having gotten a MacArthur Fellowship earlier this year—is tightly bound to her ability to confront her demons and make them get up and dance for her. Barry has even drawn a book about them: One! Hundred! Demons!, based on a sixteenth-century Zen scroll.

Almost all of Barry’s comics feature gawky, uncertain youths (mis)handling the anguish of childhood and early adulthood. She was one of the first female cartoonists—decades before Alison Bechdel (Fun Home) or Marjane Satrapi (Persepolis)—to plumb the terrors and textures of her own childhood and adolescence, spurring a trend, still going strong, of autobiographically inflected comics. In fact, the impetus for Barry’s first published work was her boyfriend’s leaving her for someone else. “I couldn’t sleep after that, and I started making comic strips about men and women,” Barry told The Comics Journal in 1989. “The men were cactuses and the women were women, and the cactuses were trying to convince the women to go to bed with them, and the women were constantly thinking it over but finally deciding it wouldn’t be a good idea.”

That comic, Ernie Pook’s Comeek—starring a wispy, hapless daydreamer named Ernie Pook and a series of prickly dogs—launched her career. In 1977 Barry’s friend and fellow student at Evergreen State College Matt Groening (creator of Life in Hell and The Simpsons) and John Keister, who worked at the University of Washington’s newspaper, both started publishing Ernie Pook’s Comeek in their respective school papers without telling Barry. Soon her strip was picked up by The Chicago Reader, and then by alternative newspapers all over the US. It became a cult favorite.

Now Barry has more than a dozen books to her name, all done in her inimitable raw, crazed, leave-no-space-unfilled style. They include compilations of her strips and two illustrated novels—The Good Times Are Killing Me (1988), the tale of an interracial friendship between two girls (based on her childhood), and Cruddy (1999), featuring Roberta Rohbeson, who lives in “the cruddy top bedroom of a cruddy rental house on a very cruddy mud road” and goes on a killing spree with her father, who runs a meat-packing business. (In Barry’s words, “It’s, like, you know, it’s a murder fiesta, and lots of knives and killing.”)

Most of Barry’s comics are, to use her own term, “autobifictionalography.” Her trademark characters, who first appeared in her comic strips in the mid-1980s—Marlys, Maybonne, Freddie, Arna, and Arnold—are fictional kids. But, as Barry has said, “I picture it; I see it happening on the streets where I grew up.” The family lived in a working-class neighborhood in Seattle; her father, of Irish and Norwegian descent, was a meat-cutter and her mother, of Irish and Filipino descent, was a hospital housekeeper. Barry herself worked as a night janitor at a hospital starting at age sixteen.

Although Barry is still best known for her comics about gritty, insecure kids dealing with sadistic parents and rejection, her work over the last decade has taken a sharp turn. Barry, who now teaches at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, has created four inspirational-instructional comics in which she plays the role of uninhibited professor: What It Is (2008), Picture This: The Near-Sighted Monkey Book (2010), Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor (2014), and Making Comics (2019). They focus on what she has learned about the drawing process—“big realizations and small ones,” as she told The Comics Journal. “The biggest one was…that the back of the mind can be relied on to create natural story order. It’s not something I have to try to do…it seems to begin to form itself if I keep moving my hands.”

Barry isn’t the first cartoonist to make comics about making comics or drawings about making drawings. There is Ad Reinhardt’s How to Look; Will Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art; Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics; Ivan Brunetti’s Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice; and Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik’s How to Read Nancy. But hers are nothing like those others, which are designed, for the most part, to teach readers about what makes comics tick. Eisner’s book, based on a course he taught at the School of Visual Arts in New York, is an analysis of graphic storytelling techniques—framing, timing, thought balloons, gesture, the relationship between words and pictures. McCloud’s wildly popular instructional volume is about the peculiar grammar of graphic storytelling. These books are unlikely to make anyone who does not already draw cartoons feel that they could do so.

Advertisement

Barry’s books could not be more different. They have a democratic, do-it-yourself feel. For the most part, they are indifferent to technique and the nuts and bolts of comics. They don’t explain thought balloons or timing or framing. Instead, they are meant to bring one’s cartooning id to the surface. Barry’s books demand that you, the reader, come along with her—calling up your own demons, stirring your own memories, and prodding yourself to make the kinds of marks only you can make. They are comics meant to get you psyched, and they are fun and funny. They are perfect for our lonely Covid moment.

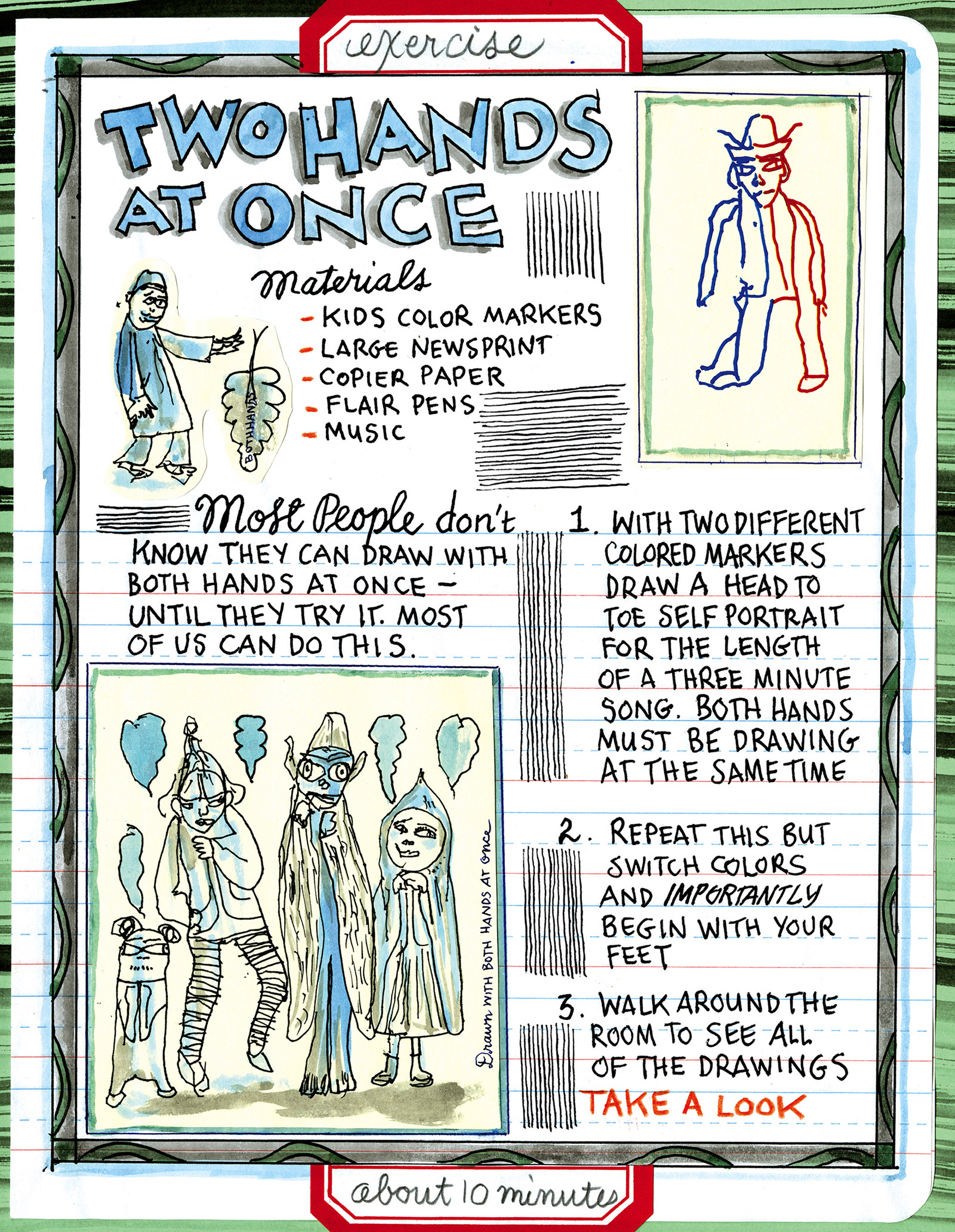

Making Comics is a book pitched to adults who want to draw but think they can’t. It has the look and feel of a school composition book, the kind with black-and-white marbleized covers, and is jam-packed with Barry’s drawings, decorations, monsters, demons, self-caricatures, lists, ideas, exercises, tricks, and prompts. It offers tons of advice: Relax! Keep your pen moving! Listen to music! Work hard! Don’t think about your drawings while making them. Don’t judge them! And whatever you do, don’t throw them away! Give them to Lynda and she will put them in her next book.

Barry wants all her students—and that includes you—to get back to the time in childhood “when drawing and writing were not separated,” when they were conjoined parts of an emotionally expressive language. Her many aliases in the book—Professor Sasquatch, Professor Peanut, Professor Skeletor, Professor Mandrake Root, and Professor Hot Dog—all want you to find your own language, your “line-voice,” or, rather, to make sure it finds you.

Come to think of it, the closest cousin to Making Comics is not a book about drawing comics at all but the 1979 classic by Betty Edwards, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. Both books demand participation. Both have a messianic spirit. Both demand you silence certain parts of your judgmental self. But Edwards’s book, which teaches you how to draw from life, relies on the intelligence of the eye; Barry’s, which teaches you how to draw from your unconscious, relies on the intelligence of the hand. Edwards’s is about “the art of realistically portraying actual things seen ‘out there’ in the world.” Barry is into another kind of “realness”: finding your expressive core. This requires letting your hand take the lead. She wants you to rediscover the pictorial fluency you once had, the kind that “moves up through your hand and into your head.”

The first step is getting you to not despise your spontaneous drawings. As she notes, “There is an energy on the first day of class—dread and hope combined.” She loves that energy and wants you to love it too. On page 4 of Making Comics Barry displays a drawing by one of her adult students, Alex. It shows a figure—I can’t tell whether it’s a boy or girl, man or woman—standing aslant on four lines that are meant to represent two legs. One foot is missing; one arm has stubby fingers, the other arm is hidden behind his or her back; the figure has short curly hair, a triangle nose, and the eyes are irregular shapes; the irises are scribbled black circles. It’s probably not the way you would want your drawings to look. In fact, it’s a dead ringer for the kinds of untutored student drawings Edwards uses as her bad “before” examples.

What does Professor Barry say about it? “There is a certain kind of drawing that I adore…. The line is unpracticed, even a little timid. It’s the line of someone who quit drawing a while ago. It’s impossible to fake.” The goal is to get beyond the self-loathing that attends such drawings, to get back to the fearlessness one had as a child of nine or ten. This age, by Barry’s reckoning (and also by Edwards’s), is when many people stop drawing because that’s when they develop standards of what things should look like, when they become disgusted by their limitations. As Barry has said, this is when, for the first time, “If you’re trying to draw a chair, you can see that it doesn’t look like a chair.” And this terrible realization is a killer for most people. It’s why they stop drawing.

Advertisement

But how to silence the judgmental part of one’s mind? First off, she tells her students to use a nonthreatening, cartoony style that has no relation whatever to reality. This is her way of tuning out that part of the mind that thinks it knows how things should appear. She recommends using a style developed by her friend the cartoonist Ivan Brunetti: For the head you draw a circle and for the body a rounded-off trapezoid. You make lively spaghetti-like legs and arms and you form snowball hands. (Everyone fears drawing real hands. so why bother with them?) You use dots and ovals for eyes and lines for mouths. That way, you won’t even be trying for reality. Dots and ovals, after all, are clearly not eyes, lines are not mouths, and snowballs are not hands.

Barry advises you to use this shorthand to draw quick full-body self-portraits on index cards with Flair pens (the supply list is simple but nonnegotiable). Three-minute songs serve as timers. Then come variations:

Draw yourself as

• an astronaut in space

• turning into an animal

• turning into a fruit or vegetable (no bananas)

• turning into a monster.

If you line up your four drawings, “we see something we could call a drawing style,” or “line-voice.”

Sadly, most people don’t ever get to see (or hear) their “line-voice” because they are cruel to their drawings: they find their spontaneous productions “intolerable,” Barry writes. “It’s more than just feeling ashamed…It’s fear. There is an urge to destroy the drawing—to snatch it and ball it up, and toss it.” For such people, Barry has a plea: “Have mercy on the unspeakable monster who has no other way to tell you it’s you.”

Barry treats such primitive drawings as if they were rescue animals—misunderstood, maltreated, poor creatures in need of protection from their original owners. To save them from harm, she takes “the drawing away from its maker as soon as it comes into being.” She has her students pass their drawings to their neighbors or to her. And then what? “Sometimes I copy them. Sometimes I draw on them, color them, cut them out.” As she notes, many of the illustrations in Making Comics are “rescued images.” Some students will be puzzled by why Professor Barry likes these “messed-up” drawings. Her response: “There is a realness in them that is hard to come by.”

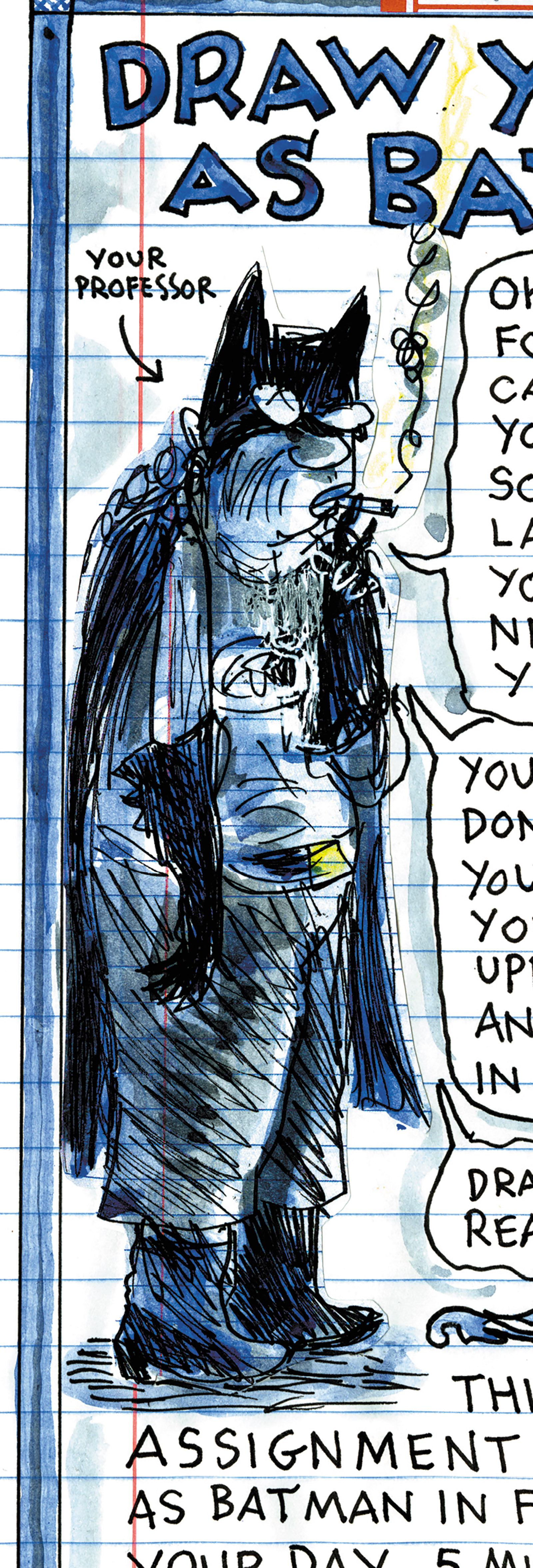

The point of her class is to build on that “messed-up” stage, to recognize the line-voice and develop it. For this, Barry has various techniques: Draw with your eyes closed. Draw in tandem with a partner. Draw with two hands rather than one. And always “keep your pen moving.” Another exercise (based on Brunetti’s teaching) requires drawing the same thing faster and faster—say, a cat, Batman, or Betty Boop: in sixty seconds, thirty seconds, twenty seconds, ten seconds, five seconds.

One of Barry’s best tricks is making “scribble monsters.” You scribble something random, then make a monster from it. “An unintended character seems to arrive whole from a scribble. It has a mood and a way of moving and a disposition toward the world around it.”

Of course scribble monsters and inner demons are not comics characters. They don’t move or talk or have histories. And tolerating your monstrous drawings is not the same as making comics. On a page titled “Make Something Happen,” Barry teaches her students to study their own drawn characters and guess how they might act: “Look at how your character is standing. What are they up to? Where are they? What’s going on?” Here you look at your scribbles as beings with desires and tastes and plans. This stage of drawing is all about empathy. (It reminds me of a certain Ernie Pook listening to his foot talking.)

In another exercise, students assign random bits of language (a line from a poem or song, an item from a to-do list) to their monsters. Writing and drawing in this way isn’t always smooth, but Barry has a cure for getting past mental blocks: “If you get stuck, just write ‘tick, tick, tick’ until the story starts up again.” The point is to lose control: “When you are lost, there draw monsters.”

This is all fantastic and fantastically encouraging, but about halfway through Making Comics I started yawning uncontrollably. I wasn’t tired or bored. I simply could not stop yawning. Maybe I was anxious. After all, I had already fallen behind the class (by buying zero percent of the supplies and doing zero percent of the exercises). Clearly, I was resisting the things Barry was asking me and the rest of her remote classroom to do. Also, I don’t like Flair pens or index cards.

Nonetheless, I found some printer paper (also required for class) and bravely dove into some of the exercises—“Scribble Monster Jam,” “Monster, Draw Near,” and “Draw Yourself as Batman.” After doing these (with a ballpoint pen, not a Flair), I was positive there was more to my yawning fit than my truancy. Looking at Barry’s students’ drawings of Batman and then at my own drawings, I saw that just about everyone (including me) can draw some kind of a Batman that possesses a certain vibe, a “line-voice.” But when I laid eyes on Barry’s own fantastic Batman, which she had drawn as a self-portrait—sucking on a cigarette, slouching a bit, with a slight paunch—I saw just how much of Barry’s method may depend on her being Barry. And I discovered a new anxiety: I’m not Lynda Barry.

She has a frenzied energy that is impossible to match. She spins crazy pictures and words. She tells us that she makes deck upon deck of index cards with ideas—people she knows, funny memories, odd places. She never gets tired of filling space with lines and colors and words. It’s infectious. There’s something about her very prompts—“draw yourself as Batman a. screaming, b. depressed, c. vomiting, d. passed out”—that is just so very much her. Even her stuck moments are ineluctably her. As she writes in her book Syllabus: Notes of an Accidental Professor, “When I start feeling too concerned that all the words I write be very smart and about something worthwhile, I find my urge to write replaced with an urge to draw monkeys.” Her monkeys have kerchiefs, glasses, and cigarettes. They are hilarious and look just like her.

I love the spirit of this book and its raucous energy; it almost makes me feel as if I could draw like Barry. But my demons are not demonic like hers, and my Batmans are not batty like hers. They look tentative, worried. I don’t know how to draw anyone passed out, much less how to draw Batman passed out. I really think I need to read Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain to even begin to see what Batman looks like in full regalia.

I’m not sure whether Making Comics will make you, or me, a better cartoonist, or a cartoonist at all. But that’s not the point. The point is just to make you a more you-cartoonist. And that’s ideal for the anxious moment we are in now. As Robert Henri said in The Art Spirit (1923), “Don’t worry about your originality. You could not get rid of it even if you wanted to. It will stick to you and show you up for better or worse in spite of all you or anyone else can do.”

This Issue

September 24, 2020

Ball Don’t Lie

A Second Chance

Making Order of the Breakdown