The pandemic has not spared books. Booksellers responded to shelter-in-place orders by skateboarding packages to curbsides, organizing Instagram reading groups, branding face masks. None of this saved revenues from plummeting. Before the first month of lockdown was over, one survey showed that 80 percent of independent bookstores had furloughed or laid off workers. Supermarkets and big-box stores that remained open cut book orders; some Walmart branches roped off paperback racks as “nonessential.” Online sales fared better, but not by much. Although printed books are easier to ship than many commodities—books were e-commerce sites’ earliest proof of concept partly because nonperishable rectangles fit in the mail—Jeff Bezos cast his company as a public utility by ostentatiously prioritizing “essential goods” such as lentils and hair dye over Amazon’s signature product. School closings cut demand for textbooks, along with most parents’ time for leisure reading. By early April, bookstore sales were 11 percent lower than they had been the previous spring.

That’s not so bad, compared to the 50 percent drop in sales of clothing. The lockdowns that depressed purchasing power also opened up time soon filled by fiction, traditionally consumed by old or female readers—that is, people stuck at home. By April, even literary preppers stocked with triplicates of Saramago’s Blindness resorted to price-gouged coloring books to stem our children’s 24/7 demands for readalouds. Books categorized as “games, activities and hobbies” sold 25 percent more—a smaller gain than markers, which spiked 81 percent. Board books, those chunky hardbacks laminated to protect against drool (and, more recently, wet wipes) sold 30 percent more in the first full week of April than they had the previous year.

Other genres weathered the crisis in digital form. Audiobook consumption, initially down as cars idled in driveways, rebounded even more spectacularly in libraries than on direct-to-consumer platforms such as the Amazon-owned Audible. In the first week of April, Overdrive, the largest distributor of e-books and audiobooks for US libraries, reported a 30 percent increase in borrowing worldwide. While nationwide statistics are not yet available, one Florida library system saw a 22 percent jump in the use of their primary e-book supplier, and a 68 percent increase for their supplier of children’s and young adult books. Lockdown changed not just how much Americans read, but what. Back in March, sales of Camus’s The Plague followed the upward curve of Covid test results. Couples stuck at home together borrowed Relationship Goals: How to Win at Dating, Marriage, and Sex. Search engines gave Nora Roberts’s 2018 thriller-romance Shelter in Place a new lease on life. The worst of times for travel guides was the best of times for cookbook downloads: What good is panic-bought yeast if you haven’t panic-borrowed books that tell you what to do with it?

Yet reading turned out to be only the beginning of what people do with books during a pandemic. Like T-shirts scissored into masks, printed matter found itself commandeered for new uses. Lacking fellow commuters from whom to screen myself, I needed to requisition my copy of War and Peace to prop my laptop to a less unflattering camera angle. Other Zoom users devised library-themed backgrounds to blot out the dirty dishes; soon, independent bookstores uploaded virtual wallpapers featuring their shelving. Bookcase Credibility, a Twitter account that rates webcam backdrops, deducted points for volumes grouped by color. When Trump brandished a Bible at arms’ length with the spine turned away from him, he was “waghorning,” a verb coined by the founders of Bookcase Credibility to describe journalist Dominic Waghorn’s practice of shelving one book on an otherwise ordinary shelf tantalizingly back to front. A new breed of advice columnists recommended positioning your laptop to make the presence of books visible while leaving their titles illegible to ward off embarrassment.

Books were becoming props, but also bunkers. In May, my Zoom screen introduced me to a “stay safe, read books” T-shirt sold by a Brooklyn bookstore to raise funds for hard-hit industry workers. Variants exhorted me to “keep safe, keep reading” and “stay home, read books.” Reading was becoming a palliative for loneliness and boredom, a virtual substitute for the temptations of hand-to-hand contact.

During earlier epidemics, on the contrary, books themselves posed the danger. Eighteenth-century officials dipped in seawater the Bibles on which shipmasters swore that their cargo had been duly disinfected. Bibliographically transmitted disease started to worry readers in the nineteenth century, once taxpayers began to support public libraries that lacked the social exclusivity of their members-only predecessors. Novels were considered especially likely (accordingly to the late-nineteenth-century novelist Rhoda Broughton) “to have been thumbed and read by convalescent scarlet fevers and mumps.” Librarians responded by inventing “book fumigators” that gassed volumes with sulphurous acid. Life would become safe, one former librarian speculated in 1890, only “when we have foregone [sic] or disinfected our books, boiled our milk, analysed our water, killed our cats, declined to use a cab, adopted respirators, and sternly refused to shake hands with our friends.” A century later, when a nurse at a New York hospital contacted the local branch library to check out books for HIV-positive readers, library volunteers refused, invoking fears for their safety.

Advertisement

The sense through which we usually encounter the page is sight. Recent events have awakened readers’ awareness of touch, nudging us to notice whose hands have touched the pages that we ourselves are turning. In the private sector, the May 1 strikes sparked by Amazon’s withholding of “personal protective equipment, professional cleaning services and hazard pay” called attention to the economic and bodily safety of the workers who packaged and delivered the reading material that whiled away white-collar lockdowns. Libraries, long one of the first places Americans turn to during a disaster, were asked to fill in for the steadily lengthening list of shuttered institutions. Some counties kept reading rooms open even after schools had closed. Others required librarians to clock in to buildings empty of patrons. At the other end of lockdown, libraries became some of the first public institutions to open, even if just for curbside book deliveries. More fundamentally, the assumption that a closed reading room implied “slumbering” workers who could be furloughed (or even, in Minneapolis, reassigned to staff homeless shelters) lent urgency to long-simmering resentment over politicians’ perception of the library as nothing more than a physical space warehousing books.

The ingenuity with which librarians repurposed book drops as mask drops and made Wi-Fi available in the parking lots outside closed branches shouldn’t distract from the remote services libraries had been providing all along. Neither e-book checkout nor online medical reference nor over-the-phone help filling out unemployment forms—all of which spiked during the lockdown—was anything new for librarians. What is new, however, is a tangle of post-lockdown questions about how to reconfigure reading rooms and “quarantine” books in between loans. Some libraries have had to warn patrons against microwaving volumes: their metal radio-frequency ID chips risk combustion.

In shifting from plague-themed novels to lockdown-occasioned reading to germ-infested woodpulp, my focus here has moved from texts to practices to objects—or, mapped onto academic disciplines, from literary criticism to history to bibliography. A homeschooling parent who gives The Plague five stars on Amazon for “Great use of vocabulary” is analyzing the novel’s verbal content; the reviewer whose own boredom is validated by noticing that passages highlighted by other readers cluster in “the first part of the first section, and the last part of the last section” is extrapolating to a history of reading habits; and the reviewer who subtracts three stars because “it may be prime fulfilled and cheap” but “the font used is COMIC SANS!” is focusing on the book as a material thing.

Those three perspectives share equal billing in book history, the discipline cobbled together in the past century out of social and cultural history, textual editing, analytical bibliography, and reception theory. That its methods could transform our understanding not just of peasants’ literacy rates and pulp fiction, but also of where our own scholarly practices come from, is one of Anthony Grafton’s crucial insights. Even in his biographies of scholars like the fifteenth-century architect Leon Battista Alberti, the sixteenth-century astrologer Girolamo Cardano, and the sixteenth-century classicist Joseph Scaliger, Grafton, the Princeton University historian who knows more about Renaissance humanism than any scholar alive and most dead, locates the individual genius within networks, workshops, and households.

Erasmus, Copernicus, and other authors whom you’ll recognize in the pages of Inky Fingers, his latest collection of essays, form the tip of an intellectual pyramid whose base teems with correspondents, protégés, servants, and even children. The great Antwerp printer Christophe Plantin, Grafton shows, trained his five-year-old daughter to read Hebrew, Greek, and Latin texts aloud to the proofreader, without understanding the words. Notes scribbled in the margins of the proofs of one Bible printed by Plantin complain in Hebrew of the girl’s tardiness, for the sake of discretion.

Grafton’s 1997 monograph The Footnote: A Curious History concretized history from below, focusing not on figures whose poverty excluded them from the written record but, more literally, on the lower parts of the printed page. The essays that make up Inky Fingers, too, repopulate the world of high scholarship with participants of all social ranks, dragging the most rarefied ideas down to earth.

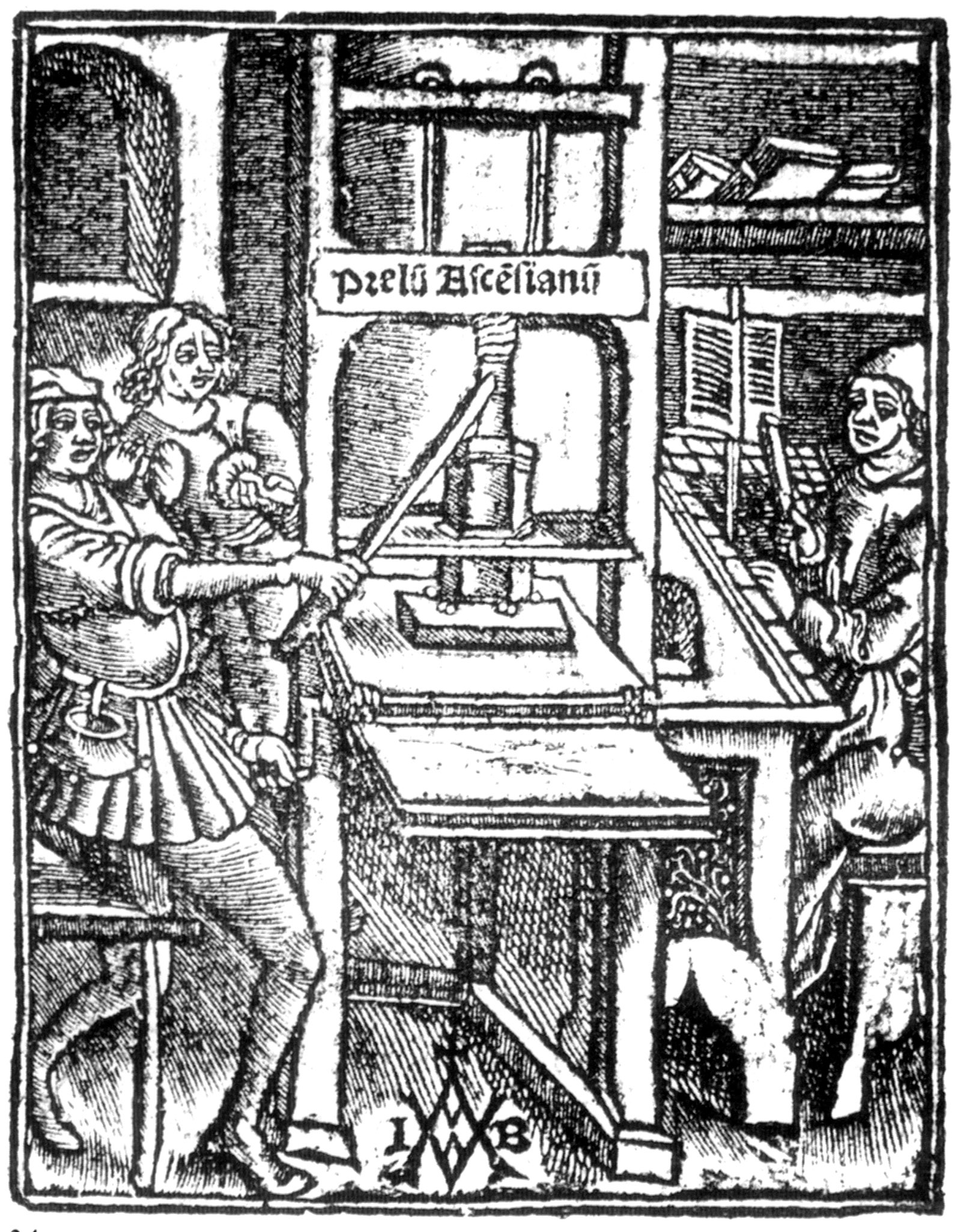

Grafton chips away at early modern scholars’ subordination of “mechanical” workers (such as compositors and pressmen) to “theoretical” workers (such as the “correctors,” usually understood as proofreaders, whose role Grafton shows to have encompassed indexing, updating, and other functions much like those of a modern editor or literary agent). Although university administrators now equate “scholarly collaboration” with public-spiritedness, the workspaces that Grafton reconstructs in such evocative detail provide a bracing reminder that teamwork doesn’t preclude inequality. On the contrary, his excavations of early modern humanists’ working methods emphasize a testily renegotiated division of labor among more or less visible actors, with the degree of acknowledgment rarely proportional to the hours put in.

Advertisement

For all his own intellectual daring, Grafton’s sympathies lie with gruntwork. Originality is upstaged by transmission, inspiration by logistics. Ideas, in this vivid telling, emerge not just from minds but from hands, not to mention the biceps that crank a press or heft a ream of paper. (The inky fingerprints left on a manuscript by the great printer Aldus Manutius, for example, make it possible to identify which base texts he worked from.) Reconstructing artisanal processes from printed products, Grafton’s omnivorous erudition lends drama to the dowdy subject that high-school teachers call “study skills”: how information is broken into manageable chunks for future retrieval.

The most striking instance of the “paper tools” analyzed in his book is the collection of excerpts hand-copied by Francis Daniel Pastorius, a seventeenth-century German immigrant to Pennsylvania. Far from a mere bucket in which derivative information was stored, this commonplace book emerges from Grafton’s analysis as a powerful “artificial memory” that shaped surprisingly radical arguments about race and slavery. Other “epistemic machines” include seventeenth-century precursors of tracing paper, made from cow embryos coated with pork fat and preserved by storage in urine. The logic underlying such low-tech duplication methods will feel uncannily familiar to any Internet user who remixes—no matter how hygienically—the words and images compiled by anonymous content providers.

The questions formulated by Grafton are recognizably bookish: Who should be credited for the production of knowledge? What traces do ideas bear of the labor that transmits them? In When Novels Were Books, the Fordham University English professor Jordan Stein uses bibliographical methods to solve a puzzle that might look purely textual: Where do genres come from? The origins of the novel, in particular, form one of the longest-running riddles of literary criticism. In 1957 Ian Watt’s Rise of the Novel sharply distinguished the realist novels that emerged in eighteenth-century Britain—secular in their ethos, empiricist in their epistemology, bourgeois in their allegiances—from the kinds of long prose narratives that were distant in time (Hellenistic and medieval romance) or in space (the more shapely, less true-to-life world of the French novel). Drawing on the social sciences as much as on literary criticism, Watt explained the messy miscellaneity of the eighteenth-century novel by the individualism of the society that it expressed.

In the decades that followed, Watt’s thesis inspired challenges from feminist critics (Nancy Armstrong’s Desire and Domestic Fiction and Margaret Anne Doody’s True Story of the Novel), Marxist critics (Michael McKeon’s Origins of the English Novel), and debates about the origins of the very idea of fictionality (Lennard Davis’s Factual Fictions, Catherine Gallagher’s Nobody’s Story). Watt’s title ramified into “Rape and the Rise of the Novel” by Frances Ferguson (1987), The Colonial Rise of the Novel by Firdous Azim (1993), Women and the Rise of the Novel by Josephine Donovan (1998), “Race and the Rise of the Novel” (the subtitle of a 2007 study by Laura Doyle), and more.

For all their disagreement, these arguments took “novel” to designate a string of words. Stein’s revisionist account of eighteenth-century print culture starts instead from objects. Granting publishers equal billing with authors and paying as much attention to buying habits as to reading practices, he coordinates the history of the novel with “the development of the book as a media platform.” One effect is to reveal an unfamiliar set of eighteenth-century generic taxonomies, which defined Robinson Crusoe and Tom Jones not as fictional prose narratives but as gatherings of printed paper in octavo or duodecimo format—by comparison, bigger than a smartphone, smaller than a laptop. Publishers’ catalogs lumped pocket-sized devotional works with similarly scaled fictions rather than with hefty, lectern-ready collections of sermons. The textual features that we usually associate with the novel—narrative mode, fictional status, density of detail—dwindle here to one element in a bundle that also enfolds characteristic material attributes, distribution channels, and reading practices.

Dipping in and out of novels as twitchily as they browsed and searched books of piety, the readers described by Stein sound more like the pen-in-hand scholars described by Grafton than the page-turning fantasists that we think of when we picture novel-lovers. Looking at the ways in which novels were used challenges the exceptionality of the genre. Watt placed the novel within a longer history of narrative, but When Novels Were Books places it instead with contemporaneous prose on both sides of the Anglophone Atlantic. Stein pairs Richardson’s pseudo-autobiographical fiction Pamela (London, 1740), for example, with the decidedly nonfictional Life of David Brainerd, a now-forgotten missionary document published a few years later in Philadelphia.

The juxtaposition isn’t in itself surprising: the New Historicists who came to dominate English departments in the 1980s invented the tactic of pairing each literary text, sommelier-like, with a more obscure nonfictional counterpart in order to show the broader cultural concerns that made both works possible. Those critics might have stopped, though, where Stein begins: by noting the vulnerable first-person speaker that narrates Pamela and Brainerd. Stein, in contrast, zooms out to the way eighteenth-century booksellers categorized the two texts. Advertised and shelved cheek-by-jowl and priced alike, one narrative that would later be relegated to the dusty categories of Religion or Biography originally sent the same commercial cues as another that would later be reprinted with the retroactive subtitle “A Novel.”

Like Grafton, Stein understands publication as a process rather than an event, and he shares Grafton’s fascination with the afterlives of texts repurposed by successive generations. It was only at the end of the eighteenth century that booksellers began to rebrand books like Pamela as novels, a category carved out by contradistinction to the equally new category of “books of piety.” The next generation of publishers went on to repackage Pilgrim’s Progress—previously treated as a religious text—as a secular novel. Watt himself acknowledged that the term “novel” emerged after the fact, as a label for books published earlier with subtitles like “history” or “life and adventures.”

While Watt celebrated a genre bursting free from the stale conventions of epic and romance, Stein casts the novel itself as the fixed point against which modern devotional genres began to emerge. He locates the latter’s innovation less in their ideas (conservative if not reactionary) than in the infrastructures that created them. The same Christian publishers who recycled worn-out content devoted all their ingenuity to identifying cheaper sites outside of London to produce books and noncommercial channels through which to distribute them: voluntary associations, philanthropic giveaways, religious factions. Novels triumphed, in Stein’s nuts-and-bolts account, less because they found exciting new conventions in which to express secular modernity than because the departure of more enterprising competitors left them the last ones standing in the sleepy world of for-profit London publishing.

That literary works are shaped by their social and economic circumstances may have startled Watt’s colleagues, but for the past few decades a sometimes naive acceptance of the findings of social historians has been the default position in English departments. The “go-it-alone literary formalism” against which Stein polemicizes, therefore, feels like a straw man standing in for historicist literary critics who focus on textual content to the exclusion of textual form. The New Historicists interpret the story in the text; book historians like Stein tell the story of how the text reached its readers.

Like Defoe describing Robinson Crusoe’s adventures as “strange” and “suprizing” in the title of that novel, scholarly monographs have every incentive to overstate their shock value. “Tilting my argument away from form may seem like an unwonted move,” Stein declares, “insofar as the long-standing dominance of formalist interpretation has not staunched the field-wide flow of new attention to novelistic formalism.” Yet book history is by now entrenched enough that many of the scholars whom Stein tags as “interdisciplinary” inhabit English departments like his.

Stein does stand apart, however, in practicing what he preaches. The prose of this monograph might have been less lively if its author hadn’t played the full media field, from nonacademic intellectual publications such as Commonplace and the Los Angeles Review of Books to the food-and-wine magazine Saveur. In the early 2000s, the former two publications had the audacious idea of bringing literary-critical and even literary-theoretical ideas to a (slightly) wider readership online than the market for university press books like Inky Fingers and When Novels Were Books. Priced higher than most books but lower than most university press releases, measuring at around six-by-nine inches, both dust-jacket-encased hardbacks ground lofty ideas in everyday things.

This Issue

September 24, 2020

Ball Don’t Lie

A Second Chance

Making Order of the Breakdown