Du Fu and Li Bai, widely regarded as the two greatest poets in Chinese history, are still quoted by dictators and businessmen, students and dissidents. Lines from their verses have been embedded in the Chinese language for more than a millennium. Both poets were born during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), at the height of its sophistication and influence. In their middle age both suffered the horrors of the An Lushan Rebellion (755–763), a catastrophic civil war whose warning signs the government had ignored. Within seven years, two thirds of the Chinese population were dead, disappeared, or displaced. The rebellion was put down with the costly military assistance of Uighur troops, but the Tang Dynasty never recovered its former unity.

About a decade before the civil war started, Li Bai and Du Fu met several times in the course of a single year, 744–745, but never again. Both were called to serve, very briefly, in the Tang court; Li Bai was later found guilty of treason and exiled. Both men—Li Bai a hotheaded, ungovernable Daoist; Du Fu, a decade younger, a doting father and upright Confucian—became internal refugees when their country imploded in the rebellion. Du Fu wrote more than a dozen poems about Li Bai, and when the older poet became a pariah, Du Fu was one of the few to defend him. Both Li Bai and Du Fu attempted to understand the political disintegration around them by taking on subjects that normally remained outside Tang poetry. Their work was startling in its artistry and breadth—and still is, in a China that is again changing rapidly. Each died convinced he’d wasted his talent, at the margins of the empire he longed to serve.

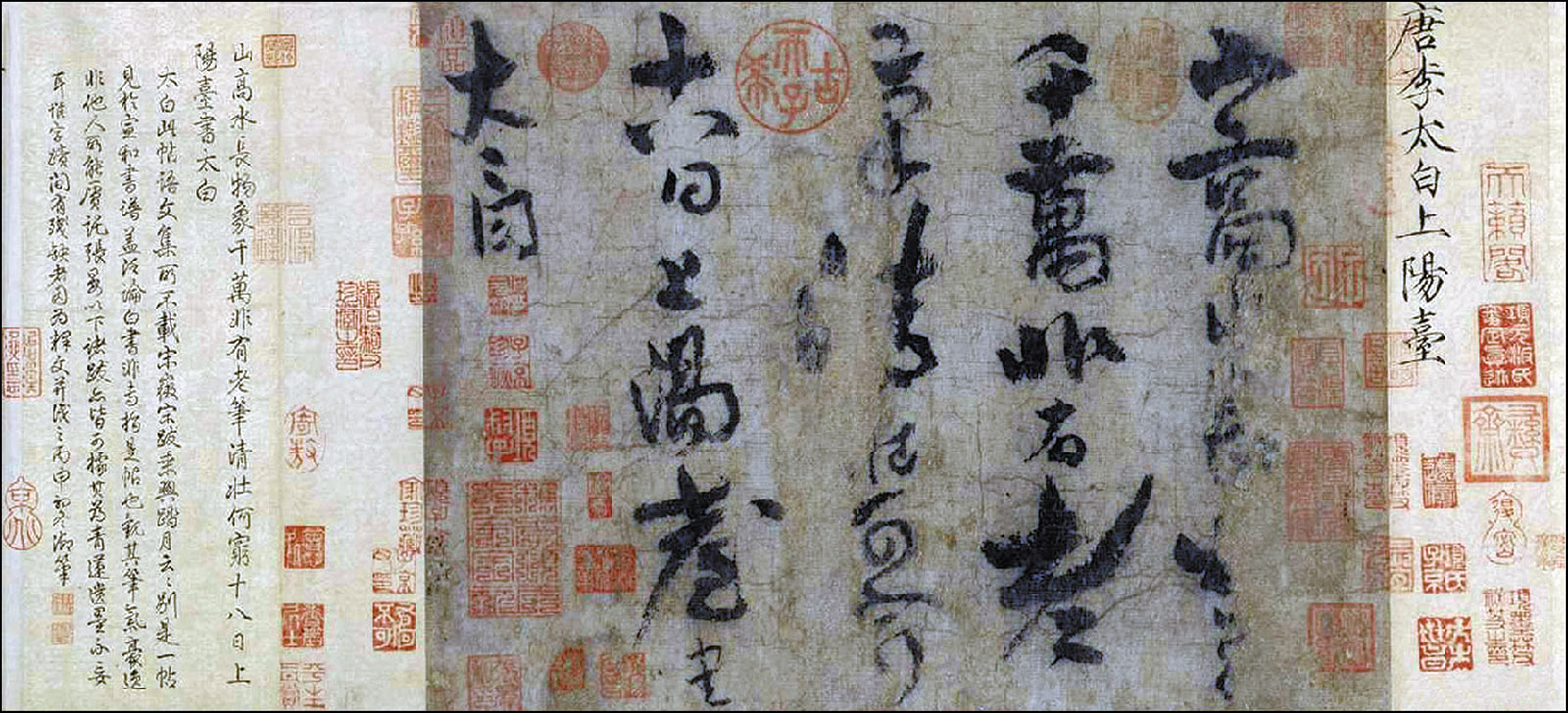

The novelist Ha Jin’s eighteenth book, The Banished Immortal, retrieves Li Bai from the legends that surround him, chronicling the life of this visionary artist in a collapsing political order. It is the first full-length biography of Li Bai in English and comes to us from a writer whose own celebrated works are banned at home. Born in China in 1956, Ha Jin was ten when the Cultural Revolution began. At fourteen, he joined the People’s Liberation Army and was dispatched to the wilderness of the Soviet border. After the death of Mao in 1976, Chinese universities reopened, and Ha Jin studied English. In 1985, at the age of age twenty-nine, he arrived in the United States to study for a degree in American literature at Brandeis University.

The 1989 Tiananmen massacre devastated him; he understood it would be impossible for him to make a life in China, and he began to write in English. Since then he has published eight novels, four collections each of poetry and short fiction, and one book of essays. He has been repeatedly denied visas to return home; he gave up applying when his mother, whom he had not seen for thirty years, died in 2014. When asked how he imagines his audience now that he writes in English, Ha Jin replied by quoting John Berryman: a poet writes “for the dead whom thou didst love.”

Ha Jin evokes the China of Li Bai as a refraction of our own moment; Li Bai’s country before the An Lushan Rebellion was “much more open than the China of our time,” but its economic inequities will be brutally familiar to anyone in today’s Shanghai, Delhi, London, or New York. Li Bai was an egalitarian, which made him beloved in the local taverns but anathema at court.

Born in 701 in what is now Tokmok, Kyrgyzstan, Li Bai was a child of the borderlands. His mother is believed to have been of Turkic origin. His father made his fortune from caravans selling fabrics, paper, and wine. Li Bai was five when the family relocated—or fled—to Sichuan province in southwestern China. This grueling six-month journey through vast deserts, wilderness, and high mountain passes exerted a hold on his imagination for the rest of his life; his description of “the wind, tens of thousands of miles long” blowing through Yumen Pass is part of the Chinese lexicon.

From the start, Li Bai showed an energetic mind, and his father hoped he would enter the civil service. As a merchant, his father belonged to a “dishonorable” part of society, and Li Bai was therefore barred from sitting for the imperial examinations. Then, as now, Ha Jin writes, “the best way to safeguard one’s interests in China has been to affiliate oneself with political power—to befriend high officials and even join their occupation.” For those of Li Bai’s background, government positions could be attained only through zhiju, recommendations made by influential patrons.

Throughout much of China’s history, poems served as calling cards, résumés, thank you notes, political tracts, spiritual meditations; they revealed a man’s erudition, temperament, and genius. At seventeen Li Bai set out to make his mark. In elite salons, his heavy Sichuan accent made him seem like “a country bumpkin in an expensive robe,” yet the ingenuity and spontaneity of his poems brought him immediate acclaim. Ha Jin provides a number of his own translations, including of “Reflection in a Quiet Night,” written when Li Bai was twenty-five (and which, for the last thousand years, “every Chinese with a few years’ schooling has learned by heart”), and the beloved long poem “Please Drink”:

Advertisement

Heaven begot a talent like me and

must put me to good use

And a thousand cash in gold,

squandered, will come again

…Since ancient times saints and

sages have been obscure,

But only drinkers have left behind

their names.

Li Bai crisscrossed the country singing his songs and writing them on walls. It was said that he could drink anyone under the table. His closest friends—barmen, recluses, farmers, aspiring officials—lent him money, gave him shelter, or shared their home brew. Listeners called him zhexian (banished immortal); he called himself “the great roc,” after the giant mythological bird. “The locals were impressed by his words,” writes Ha Jin with some understatement, “especially when he was tipsy and raving with abandon. Never had they met such a loquacious man.” But Li Bai rattled men of influence. A genius, they thought, but a loose cannon. They couldn’t risk association with such intemperance and declined to recommend him for a position—at the time a man like him might expect to be appointed to an influential government post if not directly to court.

He soon began to grasp his predicament: poets were welcome at parties and rewarded with gold and even a good horse, but they were little more than entertainment. The emperor was taxing the populace to bankruptcy and launching vanity wars. One by one, Li Bai’s closest friends retreated from the political life of the capital, and he continued to roam, leaving behind his wife, whose given name is lost to history. Ha Jin writes movingly of how she lived a “lonely married life” and observes that Li Bai’s most celebrated love poems are addressed to other women.

His writings for his wife reveal a different ache; having failed to secure a position, he was ashamed to go home. Usually drunk, he was prone to depression, and his love was “willful and somewhat selfish.” Yet for a brief time, when Li Bai gave up his quest for promotion, he and his wife found comfort together. She died shortly after the birth of their second child, and he married a second time for the sole purpose of finding a mother for his children. Ha Jin observes that his life was essentially one of “endless wanderings…as though he was doomed to remain a guest in this world.” In 727, he composed a farewell to his beloved friend Meng Haoran, and its lines have since been recited by countless Chinese who have endured separation:

My friend is sailing west, away from

Yellow Crane Tower.

Through the March blossoms he is

going down to Yangzhou.

His sail casts a single shadow in the

distance, then disappears,

Nothing but the Yangtze flowing on

the edge of the sky.

In 742, at the age of forty-one, humiliated by his repeated failure to secure a position, Li Bai was presented one day with a large red envelope. Emperor Xuanzong was personally summoning him to the capital. Jubilant, Li Bai set brush to paper: “How can a man/Like myself stay in the weeds for too long?” He became the talk of the country, especially when word spread that the emperor, in front of courtiers, had insisted on personally ladling out Li Bai’s small bowl of soup.

Bored by the “mannered and subdued works” esteemed in literary circles and standardized by court officials, Li Bai sought a new way of speaking. He found in ancient poems, the Songs of Chu anthology, folk songs, and the learned poems known as gufeng—written a thousand years earlier and prized for their incantatory power, exuberance, and raw immediacy—an artistic lineage.

His contemporaries described him reciting verses spontaneously, as if on currents of energy or madness and as intricately as a master swordsman. His admirers, Ha Jin writes, describe Li Bai “pouring out lines without premeditation. Every word, every line, and every rhyme were in place—the poem was perfectly wrought at the very first attempt.”

Li Bai gave full-throated voice to the lives of others: boat pullers, innkeepers, courtesans, weaving women, conscripts, drinkers. In “Midnight Songs,” he speaks in the voice of women whose husbands have been conscripted:

Advertisement

The emissary will start out tomorrow

morning,

So we are busy tonight sewing robes

for our men.

Bony hands are pulling cold needles

And it’s hard to handle scissors for a

whole night.

What we’ve made will travel a long

way

Though we have no idea when they

will reach Lintao.

Li Bai’s folk songs brought into Tang poetry scenes that had previously gone unnoticed: crowded taverns, thousands of men quarrying stones, the lonely aging of a river-merchant’s wife. Daoist cosmology is structured on contact between all forms, appearing and dissolving, in a continuous and self-generating fabric. Therefore, any individual has the capacity to transform the order of things, but all individuals are grist for the endless transformations of the world. Embracing paradox, Li Bai writes, “When I sing, the moon will waver,/When I dance, my shadows will be scattered.”

Such poetry has an analogy in classical Chinese painting: the artist masters a series of elements from nature (rocks, birds, mountains, boats, grasses, etc.) that are composed of formalized strokes. Art begins when the painter organizes the elements into a composition of his own and conveys them on paper in a fluid and uninterrupted session. The painting will not be revised; this art cannot be redone. The painting is a temporal gesture, an action that is born, lives, and dies. The artist must resolve or distill contradictions in the moment of composition. The highly prized quality of presence—execution, timing, skill, artistry—is revealed in the act itself.

Once a celebrity, Li Bai died a pauper in 762. Some 1,100 of his poems have survived. Ha Jin observes that he “produced a masterpiece in every poetic form of his time.” Yet he was not keen on lüshi, eight-line regulated verse, then considered the apex of Chinese poetry. He felt hemmed in by its rules, which seemed to reward technical conformity over expression and spirit.

Lüshi’s greatest practitioner was Du Fu, whom Li Bai met in 744 when the former was thirty-two years old. That year, Li Bai, fearing his enemies, left the emperor’s service at the age of forty-three. To force “a turning point” in his life, and to protect himself (those in religious orders, according to custom, could not be pursued), he chose to undergo Daoist induction rites, a series of physical tests so punishing—including kneeling under the open sky for the greater part of seven days, with hardly any food—they sometimes proved fatal. Du Fu, who had met Li Bai just a few months earlier, stayed with him through his recovery. For nearly two weeks, they “slept in the same bed, sharing a large thin quilt, their feet entangled.” Until his last years, Ha Jin writes, Du Fu “would dream of Li Bai, who had died by then, and would compose poems about him as if the light shed by Bai had never left him.” Yet this friendship seemed to have left little trace on Li Bai.

Du Fu was born into an intellectually elite family, and he seemed destined for greatness. But he failed the civil service examination at least twice. Chroniclers, puzzled for a thousand years by such stumbles, have suspected that others sabotaged him. Perhaps Du Fu was too honest, too critical in his analysis of contemporary problems; no one knows. We know that he never managed to find a position that suited him and that at some point he married, loved his wife, doted on his four children, and grew poor. He was one of the rare Tang poets to make family life the subject of his poetry.

When the An Lushan Rebellion began, he became a prisoner of war. Somehow he escaped. Throughout his life, he managed to carry more than a thousand poems with him, unable to abandon his life’s work even as he and his family were displaced. One of his children died from starvation. The major anthologies of the era ignored him; he died penniless and obscure, worried about his family’s future. Eighty percent of his surviving work was written in the eleven years after the rebellion, and the 1,200 poems that we have from that period are believed to be only a fraction of his late work.

David Hinton’s Awakened Cosmos focuses on the Daoist ontology undetected or unaddressed by most English translations of Du Fu’s poems. The fury of the An Lushan Rebellion revealed the decay of a political order in which he, a scholar-official, felt implicated; Hinton notes that his poems combine the “despair of a Confucian loss of faith” with an “almost metaphysical sense of displacement.” In nineteen essays on Daoism and translation, Hinton formulates a language to articulate “the wild”—a term he uses repeatedly to suggest that all existence is continuously transformed, and the self therein is a transient, open form.

Upright, wistful, sometimes overcome by self-pity, Du Fu wrote about fatherhood, aging, ill health, friendship, the lives of others, and a spiritual consciousness or Daoist awareness that for him was inseparable from the composition of poetry. Du Fu, observes the scholar and translator Stephen Owen in his recent translation of Du Fu’s complete works, rose and fell through more social positions than any other Tang poet: “He often seems to have entirely forgotten what normally lay outside poetry’s sphere of discourse.”1 He still feels immediate, as if he might be living in the next room.

The essential experience of Chinese poetry is all but untranslatable. Eliot Weinberger, Lucas Klein, Burton Watson, Stephen Owen, and David Hinton, among others, have set down superb translations, while noting that, in bringing Chinese poetry into English, more things go missing than in translations from other languages. Word-for-word translations, writes François Cheng in his masterful Chinese Poetic Writing (1977), can give “only the barest caricature.”2 Ha Jin describes a particular Li Bai poem as obtaining a beauty that “can be fully appreciated only in the Chinese.” Hinton observes that a particular line, severed from its radically different philosophical context, “fails absolutely in translation.” But the incommensurability of Chinese (logographic) and English (alphabetic) written systems begins the moment a mark is made. Chinese ideograms are composed of strokes, and each of the brushstrokes references others. Cheng gives this line from Wang Wei as an example, followed by its literal translation:

木 末 芙 蓉 花

branch end magnolia flowers

The character for “branch” 木 begins to transform at its tips 末 and bud into life. In the third character, 艹 (the radical for “grass” 艸 or “flower”) bursts forth from the crown of the words 芙蓉 (magnolia) and ends in 花 (flower). Further, in a simultaneous layer of images, the third character, Cheng writes, “contains the element 天 ‘man,’ which itself contains the element 人 ‘Man’ (homo),” or person. “Face” 容 is visible in the fourth ideogram, and the fifth contains 化 (transformation). Thus the line also records a human trajectory: spiritual metamorphosis and then mortality embedded in nature itself.

Many simple characters can be incorporated into a single ideogram—the word, Cheng writes, “never succeeds in completely repressing other, deeper meanings ever present within the sign”—and ideograms placed beside one another generate further significance. Transference, parallels, metonymy, and correspondences across words and lines generate a radically different poetic realm than lexical meanings produce in English-language poetry (with its own rich universe of etymologies and literary associations). Each of the twenty ideograms in, for instance, a pentasyllabic quatrain, are considered independent “sages” and personalities; words are not only denotative but have their own “reality.”

This is a difficult thing to wrap one’s head around; the dimensionality of the Chinese writing system itself is akin to a forest we walk through (where the trees keep grouping and regrouping as we move among them), rather than a series of twigs arranged on a surface. Cheng observes that the writing system “has refused to be simply a support for the spoken language: its development has been characterized by a constant struggle to assure for itself both autonomy and freedom of combination.” To add to the constellations of meaning within any given poem, the disciplines of poetry, calligraphy, and painting are not considered distinct but rather facets of a single complete art.

Hinton notes that the Chinese language is not constructed around “a center of identity”; each time we see an “I” in a translation of Tang poetry, it was almost certainly not in the original text. Chinese grammar—a genderless and verb-tense-less system in which past, present, and future are inferred by context—allows for a complex blurring of subjectivities, which is not just a side effect but a fundamental aspect of the language. In Chinese poetry, fiction, and philosophy, the “I” is not the nerve center from which thought and knowledge begin.

Hinton’s austerely beautiful translations assume that Chinese classical poetry cannot be severed from philosophy. Guided by each poem, he translates and interprets Daoist concepts, refined over millennia, for which there are no precise English equivalents (just as, for example, Heidegger’s “dasein” carries a web of thinking that cannot be replaced by a conventional English word). We can translate the words, but in doing so, to borrow a phrase of Cheng’s, “nothing is truly translated.”

Du Fu’s “Spring Landscape” appears to non-Chinese readers like a block of ice, outwardly even and unified:

国破山河在

城春草木深

感时花溅泪

恨别鸟惊心

烽火连三月

家书抵万金

白头搔更短

浑欲不胜簪

The poem is an experience; it’s trippy. Meaning is generated across its various planes—across couplets and images, vertically and horizontally. Hinton’s translation maintains the couplets that are the basic unit of Tang poetic forms, and he creates his ice-cube shape by enjambing the lines:

The country in ruins, rivers and mountains

continue. The city grows lush with spring.Blossoms scatter tears for us, and all these

separations in a bird’s cry startle the heart.Beacon-fires three months ablaze: by now

a mere letter’s worth ten thousand in gold,and worry’s thinned my hair to such white

confusion I can’t even keep this hairpin in.

In an essay that follows, Hinton notes that the opening is “possibly the most famous line in Chinese poetry” and that the poem is a sharp and unexpectedly wry observation of man-made tragedies overrun by the endless coming-into-being of the ten thousand things (all that exists, in the idiom of Chinese philosophy). Du Fu tells us that birds seem to cry for us, and blossoms weep. Of course, this is a fairy-tale view, and “in the knowledge of its falsity, heartbreaking.” Du Fu’s discomfiting joke at the end both overturns and accepts his fear and anxiety.

Hinton’s aim is to explore the most complex ideas of Daoism—emptiness 虚 (xū), absence 無 (mó), quiet solitude 幽 (yōu), Dao appearing of itself 自然 (tzu-jan), acting without the metaphysics of self 無為 (wúwéi), and more—as expressed in Du Fu’s work. In essence, he wants us to learn words again, and to momentarily set aside the philosophical assumptions of the English language. Here, for instance, is a couplet from Du Fu’s “Standing Alone,” containing an image of two white gulls. Hinton begins with the Chinese original and a literal translation:

float drift attack strike convenient

laze ease go come wander

This is how he renders that couplet into idiomatic English, describing two gulls that

laze wind-drifted. Fit for an easy kill,

to and fro, they follow contentment.

Here we can glimpse some of the parallelisms visible on the image level: float-laze, drift-ease, attack-strike, and go-come. Lüshi poetry has strict rules governing symmetry and opposition of images and concepts, as well as tonal (the “level” and “deflected” tones of the spoken language) and rhyme patterns within lines and across couplets. Parallelism becomes, as Cheng writes, “a system turning on itself,” a dialectical mode of thought that creates inner tensions subject to resolution or release.

Each of Hinton’s nineteen essays is preceded by a translation of the poems he discusses and a specific philosophical term at work within it. (These translations and many others are available in Hinton’s recently expanded edition of Selected Poems of Tu Fu.) “Standing Alone” ends with an image of frosted grass and hanging spiderwebs as the poet, a refugee fleeing with his family, awakens to the future where a “loom of origins/tangling our human ways” casts him into despair: “I stand/facing sorrow’s ten thousand sources.” That loom—天機 (tiānjī)—writes Hinton, stretches back to our origins, and

to actually dwell there is to inhabit a place prior to thought and language, an inner wilds about which nothing can be said. And that is where this poem ends—a depth of dwelling in which Tu can only say that he is standing alone there. Or is he? “I” seems at first the most obvious way to fill in the empty grammatical space at the beginning of the last line…. But the subject of the penultimate line also carries over as a possible subject for the final line: “loom of origins.”

With the last sentence folded in this way, the loom of origins—which continuously generates existence and into which all things will vanish—becomes the subject standing before sorrow’s ten thousand sources. The “I” exists and dissolves, but not without altering the loom.

Hinton’s translations have always gone against the grain. He has been building, translation by translation, an English language for a Chinese conceptual world. His versions get closest to what makes Du Fu sublime for Chinese readers. He isn’t afraid to baffle us; the gaps remind us that we are only guests here, and that the poems do—indeed should—hover a bit beyond our grasp. In the twentieth century, Chinese poetry was translated into the American idiom by modernists like Ezra Pound and later poets including Kenneth Rexroth and Gary Snyder with a lightness of touch, a beguiling simplicity. Hinton is after the opposite: depth and boundlessness. Here is his translation of “Facing Snow”:

Enough new ghosts to mourn any war,

and a lone old grief-sung man. Broken

clouds at twilight’s ragged edge, wind

buffets a dance of frenzied snow. Ladle

beside my jar drained of emerald wine,

flame-red illusion lingers in the stove.

News comes from nowhere. I sit spirit-

wounded, trace words empty onto sky.

Hinton’s unconventional study of Du Fu privileges the poems themselves, which are all scholars have ever really had to piece together the man. He observes that Du Fu, as his world collapsed, was trying to awaken language itself: “To include all of experience equally, rather than limiting it to privileged moments of lyric beauty or insight,” and thus to express a “relentless realism” synonymous with consciousness itself.

The question of why Du Fu and Li Bai are still so revered is a suggestive one. Both were extremely erudite scholars with a deep respect for the poetic traditions they inherited. They were also reformers. They broke open Tang forms and invested them with more inventiveness, in more poems, than anyone had before. The mystery of their meeting adds to the intrigue. Du Fu had no doubt that Li Bai’s works would last forever, and Li Bai, though less effusive, was kind to the unknown, obscure, and rather earnest Du Fu. They were both poets of genius who crisscrossed the country and experienced debilitating poverty. They were shamed by the ways their rulers abandoned the people, egotistically propelling them to war.

Is this why they’ve lasted? Generation after generation, their words recall the tragedies provoked by corrupted power and testify to the keen clear eye of the poet. To read them is also to live out the belief that daring writing outlasts even emperors.

This Issue

October 8, 2020

Our Most Vulnerable Election

The Cults of Wagner

Simulating Democracy