On June 29, 1920, the Syrian envoy Habib Lutfallah stood before a committee of French senators in the Luxembourg Palace, that vast, baroque monument to France’s grand siècle. He had come to Paris to make a plea for an autonomous Arab state in the lands of the defeated Ottoman Empire. It was late in the day, and the odds were very long: France’s Army of the Levant was already massing in what is now Lebanon, preparing to march eastward and impose a neocolonial regime on Damascus.

Lutfallah appealed first to the senators’ consciences, arguing that Syria was a civilized country capable of governing itself. But he also had the wisdom to tell them that France would be better served by a whole and independent Syria than a cluster of weak and fractious states. “In Balkanizing Asia Minor,” Lutfallah said, “in multiplying small principalities, dust particles of states, [France] leaves the road open to the anarchy that will create an endemic state of war.”

The senators were not moved. The French conquered Damascus less than a month later in a bizarre and unequal battle that pitted loyalist African conscripts armed with tanks and machine guns against a ragged force of Syrians equipped with sticks and swords. (“We can crush a few negroes” was one of the Syrian battle cries.) The British, meanwhile, imposed their own rule over Iraq, where they strafed and bombed the people of that newly established country into submission.

The Europeans tried to cast themselves as liberators: they had vanquished the Ottoman Empire, which had ruled the Middle East for centuries. But they imposed new borders that cut across some of the region’s ancient trade routes and ethnic enclaves and set up new national governments with their own satraps in charge. Their rhetorical concessions to Arab sovereignty—intended mostly to appease US president Woodrow Wilson, the period’s great champion of national self-determination—were hollow. Even British prime minister David Lloyd George conceded that the mandate system established by the new League of Nations was nothing but “a substitute for the old Imperialism.”

A century later, it is easy to see Lutfallah’s warning as prophetic. The anarchy and endemic war he spoke of are now a daily reality in much of the Middle East. The roots of this ongoing tragedy are not simple, but they can be traced at least in part to Europe’s redrawing of the postwar map in London and Paris and San Remo. To the people of the region, those neocolonial dictates have acquired a mythic status as a kind of original sin. Arab schoolchildren are taught early about the villainy of Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, the British and French officials who outlined the new borders in a secret agreement in 1916. Even ISIS adheres to this interpretation of Arab history: after it captured Mosul in 2014, its fighters bulldozed the earthen berms marking the border between Syria and Iraq and declared (prematurely) that they had achieved “the end of Sykes-Picot.”

Many Westerners familiar with this history may not know that the Arabs did have a brief moment of independence and democratic experimentation in Syria, between the collapse of the Ottomans after World War I and the assertion of French rule in 1920. This period of slightly less than two years is the subject of Elizabeth Thompson’s illuminating new book, How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs, which breaks new ground in its discussion of the efforts of Syria’s short-lived National Congress to fuse liberal constitutionalism and Islam. This synthesis—the creation of an ideological common ground—is immensely important because its absence has wreaked havoc in the Arab countries ever since. One reason for the failure of the 2011 uprisings of the Arab Spring was the unbridgeable divide between Islamists and liberals, a divide that is partly a legacy of the colonial period and has been deftly exploited by the region’s dictators.

Thompson is a historian at American University who has written extensively on evolving conceptions of justice in Middle Eastern societies. Her previous book, Justice Interrupted: The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East (2013), analyzed various reformist movements and figures from the last two centuries. Her new one is aimed at a more general audience, and she has oversimplified the moral contours of her tale a little, likening one French administrator to Iago and playing up the Syrians’ hunger for democracy. But she succeeds in restoring the strangeness, and the lost potential, of this aborted moment of self-rule.

Syria was a shattered country in 1918, its landscape burned and pillaged, its inhabitants emaciated from years of famine. It was also alive with new possibilities, as people slowly recognized that the Ottoman order, with its static hierarchies of pasha and notable and peasant, was dying. One contemporary described Damascus in language that recalls Orwell’s evocation two decades later of revolutionary Barcelona as a place where “servile and even ceremonial forms of speech” fell away during the short-lived Spanish republic:

Advertisement

Freedom in all its aspects ruled—including freedom of association, speech, and publishing—which were envied in other parts of Syria and Egypt. The exaggerated salutations and aggrandizements of officials and notables (that Damascus was famous for) disappeared. People sensed their own honor and dignity.

Beyond Damascus, Syria’s identity was up for grabs, its borders wildly uncertain. Most Arab nationalists considered Bilad al-Sham, or Greater Syria, to include all or most of what is now Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan, as well as part of present-day Turkey. But some influential figures in Aleppo were lobbying for union with the new republic being formed to the north in Turkey. Most of the Christians in Mount Lebanon and the Alawites of the northwest—a downtrodden group who feared the Sunni Muslim majority—sought the protection of France. To the south, the Zionist movement was reshaping the demography and future of Palestine.

Nor was there any unifying political ideology. Arab nationalism, as the Iraqi historian and politician Ali Allawi (now Iraq’s finance minister) writes in his biography of King Faisal I of Iraq, was “an evolving idea and its adherents ranged across the entire spectrum of political opinion.”1 Some justified their break with the Ottomans on religious rather than national grounds, arguing that Turkish rule had been insufficiently Islamic. Many pined for a new caliphate, to be centered in Mecca or perhaps Mosul, and led by an Arab.

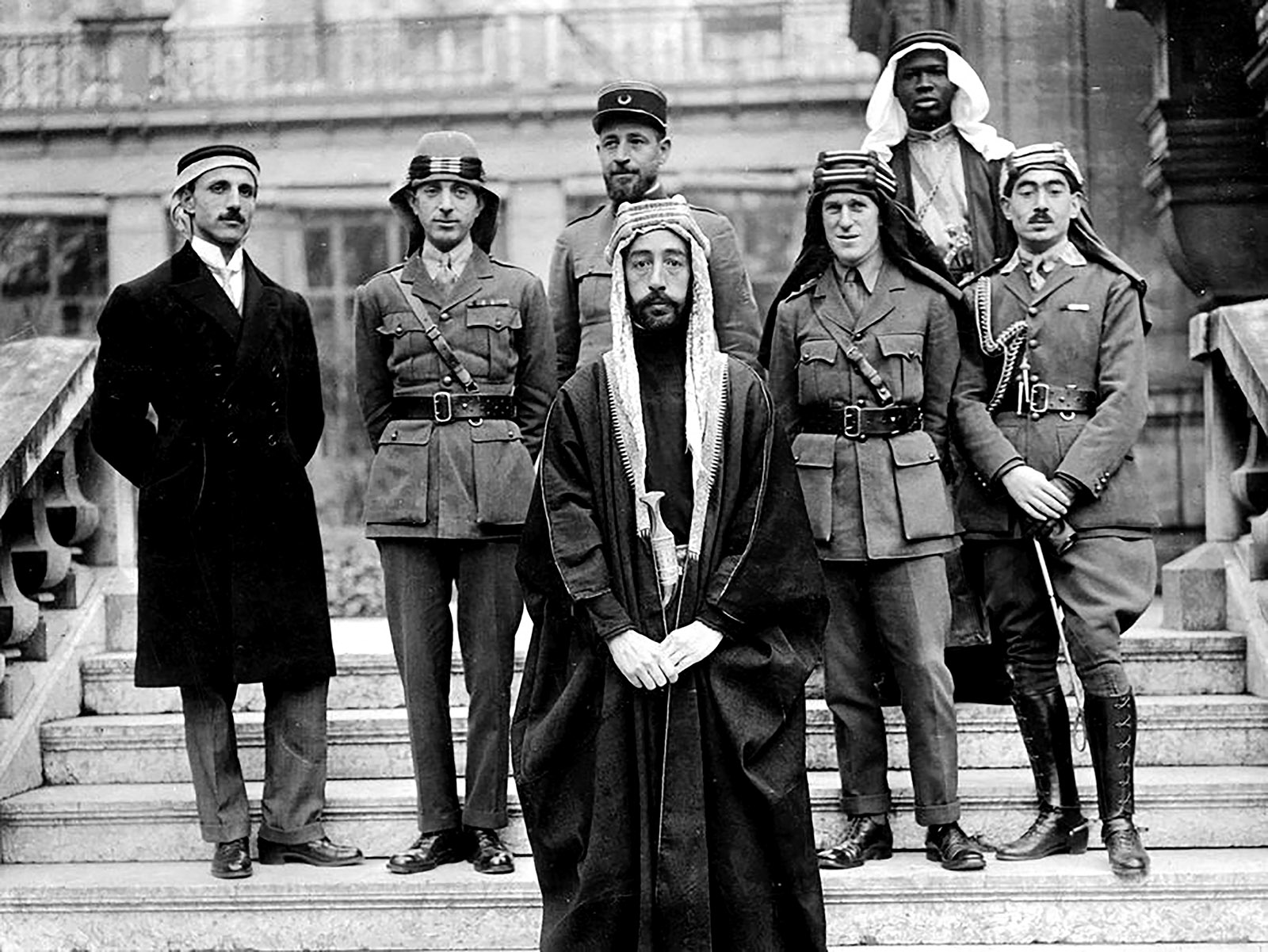

The most obvious candidate to head such a state was the leader of the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans, the man who would become King Faisal. Faisal bin Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi was a war hero and the son of the sharif of Mecca, and that combination gave him immense legitimacy. Many men and women found Faisal irresistible. “His face was one of the most attractive I have ever seen, beautifully shaped, with clear, dark eyes,” wrote one member of an American delegation in 1919. Even the straight-backed British commander, General Edmund Allenby, could not help remarking that Faisal’s “hands are as fine as a woman’s,” though he was “a strong-willed man with upright convictions.”

Faisal’s most important admirer was T.E. Lawrence, the British officer, diplomat, and mythmaker who fought alongside him against the Ottomans and helped him become Syria’s first king when the war ended. Both Thompson and Allawi present Faisal as a man of enormous gifts who found himself in a tragic position, caught between the arrogance of the Europeans and the Syrians’ demands for total independence. Faisal’s instinct was to find a middle ground, but by the end of his time in Syria there was none.

The real hero of Thompson’s story is equally magnetic but less well known in the West. Rashid Rida was an Islamic reformer and intellectual who began dreaming of an independent Syria years before the Ottoman Empire fell. Born just outside the Syrian coastal city of Tripoli (now in Lebanon), Rida moved to British-ruled Egypt in 1897 to escape Ottoman censorship and to study with Muhammad Abduh, an influential Muslim thinker. The following year he founded a reformist journal in Cairo called The Lighthouse and built a global reputation writing for it. He appears to have hedged his bets during World War I; he had no love for the Turks, but he considered the caliphate, based in Istanbul, an essential institution for all Muslims, and he worried that an Allied victory might mean European interference in Arab lands.

In October 1918 Rida heard that Faisal had ridden into Damascus, having vanquished (with considerable help from the British) the Ottoman garrison and its confederated band of German soldiers. With Faisal was a group of exultant young friends and advisers who had been dreaming of an autonomous Arab state for years. They belonged to a secret league called al-Fatat (the Young Arab Society), formed during the twilight years of the Ottomans. They knew that the British and French, who had carved up the Levant between them two years earlier, were an obstacle, but they were giddy and optimistic. So was Rida. He was still stuck in Cairo—the British wouldn’t give him a travel pass—but he was so excited about the new Syrian state that he began drafting a constitution almost immediately.

Rida didn’t get to Damascus until late 1919. He was a portly man of nearly fifty-four, and his cleric’s gown and turban stood out among Faisal’s younger acolytes, who often wore European clothes. He brought a welcome gravitas to the state-building effort, and within a few months he became the president of the new Syrian National Congress. He had thought more deeply than anyone else about the issues the Congress would face. As early as 1915, when the war’s outcome was far from clear, he had sketched an “organic law” for a future Syrian nation that would enshrine popular sovereignty and separate religion from the state.

Advertisement

Four years later Rida became an essential intermediary between secular liberals and religious conservatives in the Congress. They disagreed on a number of fundamental issues, including the political status of Islam, the balance of power between king and Congress, and, perhaps most sensitive of all, the relative influence of the country’s religious and ethnic minorities. Syria still had a sizable Jewish community, as well as large groups of Druze, Christians, and Alawites (who were then widely considered non-Muslims). Many of them were profoundly anxious about their future, and with good reason: the Armenian genocide had just taken place only a few hundred miles to the north.

The compromise Rida oversaw was far ahead of its time. The constitution named Islam as the religion of Syria’s king but said nothing about the religion of its people, and the delegates came close to granting women’s suffrage at a time when women still could not vote in France. The question of sovereignty was difficult, and it came to a head during a confrontation between Rida and Faisal in March 1920: the members of Congress had voted to make the cabinet responsible to them, not to the king. This infuriated Faisal, who saw himself as the Congress’s, and Syria’s, final arbiter. “I am the one who founded it and I don’t give it the right to obstruct the government,” Faisal told Rida when they met in the palace. “No, it is the Congress that appointed you!” Rida replied. In the end, Faisal backed down and conceded the superior authority of the Congress.

Thompson calls this exchange “a legendary moment in Syrian history.” She sees Rida and his associates as betrayed heroes, and her book invites us to imagine an alternative outcome. If not for the French invasion, Syrians might have had a say in setting their own borders and in shaping their first attempts at national identity. The country’s new institutions would not have carried the taint of colonial tutelage, and Syria’s political factions—especially its liberals and Islamists—might have been more willing to find common ground.

There is some reason to believe they could have succeeded. In the final decades of Ottoman rule, an idea of pluralist coexistence had been taking shape, according to the historian Ussama Makdisi, who has called it the “ecumenical frame.”2 It was represented in part by the Ottoman Decentralization Party, which attracted Rashid Rida and other Arabs hoping for more latitude and autonomy. Rida was inspired by the Young Turk revolution of 1908, which restored a more liberal constitution and allowed multiparty politics to thrive. Many Christians also saw promise in the idea of a looser, more tolerant incarnation of the Ottoman Empire. These ideas persisted after the Ottomans fell, and it is tempting to think that Rashid Rida and King Faisal might together have built a Syria that balanced religiosity and tolerance, diversity and order.

Behind this wishful fantasy lurks a political point, and Thompson states it bluntly in her preface. She aims, she writes,

to slay the demons that still misguide our media and our policy by demonstrating that the true cause of dictatorship and the antiliberal Islamist threat lies in the events of a century ago, not in the eternal traits of so-called Oriental culture.

This line brought me up short. I’ve met plenty of Western diplomats and soldiers while reporting in the Middle East over the past two decades, and while some of them had predictably crude ideas about Arab culture and religion, I doubt those ideas had much influence on foreign policy. Perhaps some polemical overstatement is forgivable in a preface aimed at Western readers. It is certainly true that the twenty-year French mandate distorted Syria’s political culture. But Arab democracy faced many other obstacles, some of them generated by the six centuries of Turkish rule.

Even the democratic achievements of the Syrian Congress may be slightly deceptive, because Rida and his fellow constitution-writers were performing for an audience. They believed a display of Western-style self-government just might win them enough international sympathy to stave off a French invasion, and that conviction affected everything they did during their twenty-two-month experiment. Faisal spent much of it in Paris and London, pleading his cause to European statesmen while his country floundered.

He had little choice. Wilson, Lloyd George, and French prime minister Georges Clemenceau’s priorities were in Europe, and it was all Faisal could do to get their attention. He was keenly aware that his every word and gesture would count; even his choice of clothes carried potential political meaning. When he delivered his plea for Arab independence at the Paris Peace Conference in February 1919, Faisal chose to wear his Arab robes and scimitar. But soon afterward he began wearing a tunic and trousers around Paris, with a long overcoat. Emphasizing his native culture, Thompson writes, “had been a gamble. While it had attracted public notice, it had also invited Europeans to regard him as an exotic and medieval Oriental out of the Arabian Nights stories.”

This theatrical aspect of Syria’s struggle for independence may have reached its crescendo in June 1919, when an American delegation arrived with the aim of assessing Syria’s capacity for self-government. The King-Crane Commission had been dispatched to the Middle East from Paris at Wilson’s insistence, flouting the preferences of the British and French. He had told the Europeans that he “had never been able to see by what right France and Great Britain gave this country away to anyone.” He appointed his friend Charles Crane, a well-traveled heir to a plumbing-parts empire and a lover of Arab culture, as the group’s coleader and chief spokesman, along with the scholar Henry King.

Faisal saw the commission’s visit as a crucial audition, as did his Fatat advisers. He feted its members with lavish banquets, and over the following days a series of Syrian delegations presented the Americans with signed petitions and pleas for independence. One group told them that Syria would accept only an American mandate, because “America loves humanity, entered the war on behalf of oppressed nations, will not colonize, and is very rich.” Another was led by Muslim women, who passionately rebutted the condescending stereotypes often heard in the West:

Realizing that all we have suffered has been the result of subjugation…we crave for ourselves not merely independence of existence, but the right and opportunity to a development which will assure us a place among the responsible nations of the world.

Thompson narrates these scenes with great sympathy and appears to believe that something true and authentic is whispering to us across the decades. Other historians have been more skeptical.

There was a deliberate (and successful) campaign to shape the commission’s views, including leaflets in the streets calling for Syrians to maintain intercommunal harmony during the visit. The elite figures who scripted these efforts were, in effect, tailoring themselves to a Western audience, and that may have limited their engagement with their fellow Syrians. In Divided Loyalties (1999), a fascinating study of mass politics in Faisal’s Syria, James L. Gelvin writes that

the nationalist elites who prepared for the commission’s arrival designed their demonstrations and propaganda campaigns for the purpose of presenting to an outside audience an image of a sophisticated nation eager and prepared for independence. But in the process of converting Syria into a large Potemkin village, they failed to integrate the majority of the population into their nationalist project.

Syria’s workers, peasants, and tradesmen had little stake in Faisal’s national ambitions, and some of them later joined their own anticolonial movement, one that was more religious and more violent.

A similar self-consciousness permeated the writing of Syria’s constitution during the spring and summer of 1920. It was an extraordinary achievement, which the French clearly recognized: after imposing the mandate, they did everything they could to stamp out all memory of the constitution and the democratic promise it appeared to suggest. (Thompson spent months trying to find an original copy and was unable to.) But the constitution was written partly as an exercise in public relations, to prove a point to the world.

The message went unheard. By the time the King-Crane Commission returned to the United States, Wilson had had a stroke from which he would never fully recover. The commission’s report, a robust endorsement of Syria’s capacity for self-rule, was filed away and not published for two years. There was a fair amount of American sympathy for the report’s conclusions, but no real willingness to get involved in a Middle Eastern conflict. France’s colonialists bulldozed over all objections.

Faisal made a last-minute effort—against popular resistance—to accept a French mandate, in the hopes of averting war and preserving his government in some form. His commanders had already told him they had so few bullets and trained soldiers that the battle might only last minutes. But his message to the French army command did not arrive until after the troops had left their camps and the call to jihad had gone out from the minarets of Damascus. The battle that took place at Maysalun on July 24, 1920, was a massacre: more than 1,200 Syrians were killed and only forty-two French.

Faisal was allowed to leave the country afterward, and the following year his British friends drafted him to become the first king of Iraq. That venture went much more smoothly. Backed by British guns and airplanes, Faisal held onto his second throne, though the trauma of the country’s violent birth took its toll. When he died in 1933 he was only forty-eight, but looked a dozen years older.

The French colonial administration that succeeded Faisal’s government in Syria made no effort to respect the country’s sovereignty. It embarked on a cynical campaign to separate sectarian communities from one another and cities from rural areas, playing especially to Christian and Alawite fears of Muslim fanaticism. After a revolt broke out in the Druze countryside in 1925, the French crushed it violently, killing thousands of rebels and leveling much of Damascus and other cities with artillery fire.

In Thompson’s account, French colonial policy is personified by Robert de Caix, a manipulative, pointy-bearded aristocrat who derided his opponents as “Wilsonian nitwits.” He is a deliciously odious character, but to focus on him is to eclipse some of this story’s larger setting. France’s conduct in Syria was driven less by a thirst for conquest than by a fatal misalignment. Europe was consumed by its own trauma: a war more destructive than anything humanity had ever known. Britain had suffered almost a million dead; France had lost some 1.7 million. The statesmen who met in Paris could not return to all those war widows without some recompense, some measure of gloire to honor the fallen, even if it came in the form of a Syrian satrapy. They also believed that balancing French and British imperial claims would help secure the peace. The war, after all, had been ignited in part by a failure to maintain equilibrium among Europe’s interlocking empires.

Even so, French opinion on Syria was not uniform. Clemenceau, the grand old man of the French left, was an enemy of colonialism, as was most of the Socialist Party. But the jingoists won out, and most French people were too exhausted by war to care. Only a handful of Europeans knew enough about Syria to see past the crude distortions in the press. At least two French colonial officers in Damascus—Edouard Cousse and Antoine Toulat—sympathized with Faisal and seem to have understood that imposing military rule would lead to disaster. They were overruled, like so many perceptive junior Western diplomats from India to Vietnam to Iraq.

Although Thompson does not speculate about it, it is also possible that Faisal’s kingdom would have collapsed even if the French had left him alone. Syria was desperately poor and had been utterly dependent on British and French subsidies. Syrians were divided along lines of sect, class, region, and ethnicity—and not just because of French manipulations. Many Christians and virtually all Alawites resisted Faisal’s rule. The very idea of a secular government was widely contested. Even Rida conceded that most Syrian Muslims found it unfamiliar and illegitimate, and said “they would overturn it in favor of a religious one at the first opportunity.”

Rida often seems to have felt the same way. For all his relative liberalism on some subjects, he also believed passionately that the Arab world needed a caliphate—an idea that was later taken up by Hasan al-Banna, the Egyptian founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, who considered Rida a mentor. After the new secular government of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk dissolved the Ottoman caliphate in 1924, Rida began hungering for a replacement, and his thought took a more conservative turn. If Syria had been spared by the French, he might eventually have pushed its government in a more Islamic direction.

Religion aside, the idea of equal citizenship faced heavy resistance from Syria’s paternalistic elite and its suspicious communal leaders. These traditional attitudes—engrained by centuries of Ottoman divide-and-rule policy—persisted long after Syria finally gained its formal independence in 1946 (the French had effectively been evicted five years earlier, after the defeat of Vichy French forces by the British). One renowned Syrian diplomat, Adnan al-Atassi, wrote of his dismay after attending the opening session of the new Syrian parliament in 1943, when it became clear that what he called “al za’ama al-shakhsiyya” (“personal leadership,” meaning more or less rule by strongmen) was taking precedence over law and the constitution.

Thompson appears to believe that these postwar struggles reflect a colonial distortion and not the legacy of earlier traditions. Two decades of French rule, she writes, “utterly transformed Syria’s political landscape” and paved the way for the police state that has held the country in its grip since the 1960s. Here again, I find her emphasis on French villainy a little excessive. Syria’s dreaded security services probably owe more to the legacy of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, who starting in the 1950s built the prototype of the modern Arab dictatorship that was imitated across the Middle East. The French legacy was not all bad. The educational and industrial institutions they built helped the country to thrive in the years after World War II, when Syria’s economy grew at 6 to 8 percent a year. Vast cotton and grain farms sprang up in the rural north and east, and the Jazeera region became a breadbasket. The French-designed parliamentary system, for all its flaws, offered a measure of political freedom, and political parties and newspapers flourished.

The French do bear a heavy burden of responsibility for empowering a downtrodden group whose sectarian fears helped to shape modern Syria. It was during their mandate that the colonial authorities, suspicious of Syria’s Sunni Muslim majority, began packing the security services with recruits from the religious minorities. Alawite officers eventually took control of the military, and in 1970 one of them, an air force pilot named Hafez al-Assad, installed himself as dictator. His son, Bashar al-Assad, now presides over a Syria that is in ruins after almost a decade of civil war.

Although the fighting has mostly subsided, the future looks darker in many ways than it did a century ago. Assad has bargained away much of his sovereignty to Iran and Russia. The northeast is a lawless desert, crisscrossed by Kurdish rebels, Turkish-backed militias, and jihadists. Punishing sanctions and the economic collapse of Lebanon—Syria’s financial gateway to Western markets and banks—have brought many people to the brink of starvation. Cities like Aleppo, gutted by years of bombing and shelling, will not be rebuilt soon. Perhaps things would have been different if the Syrians had been left to govern themselves a century ago. It is hard to imagine a bleaker landscape than the one they face today.

This Issue

October 8, 2020

Our Most Vulnerable Election

The Cults of Wagner

Simulating Democracy