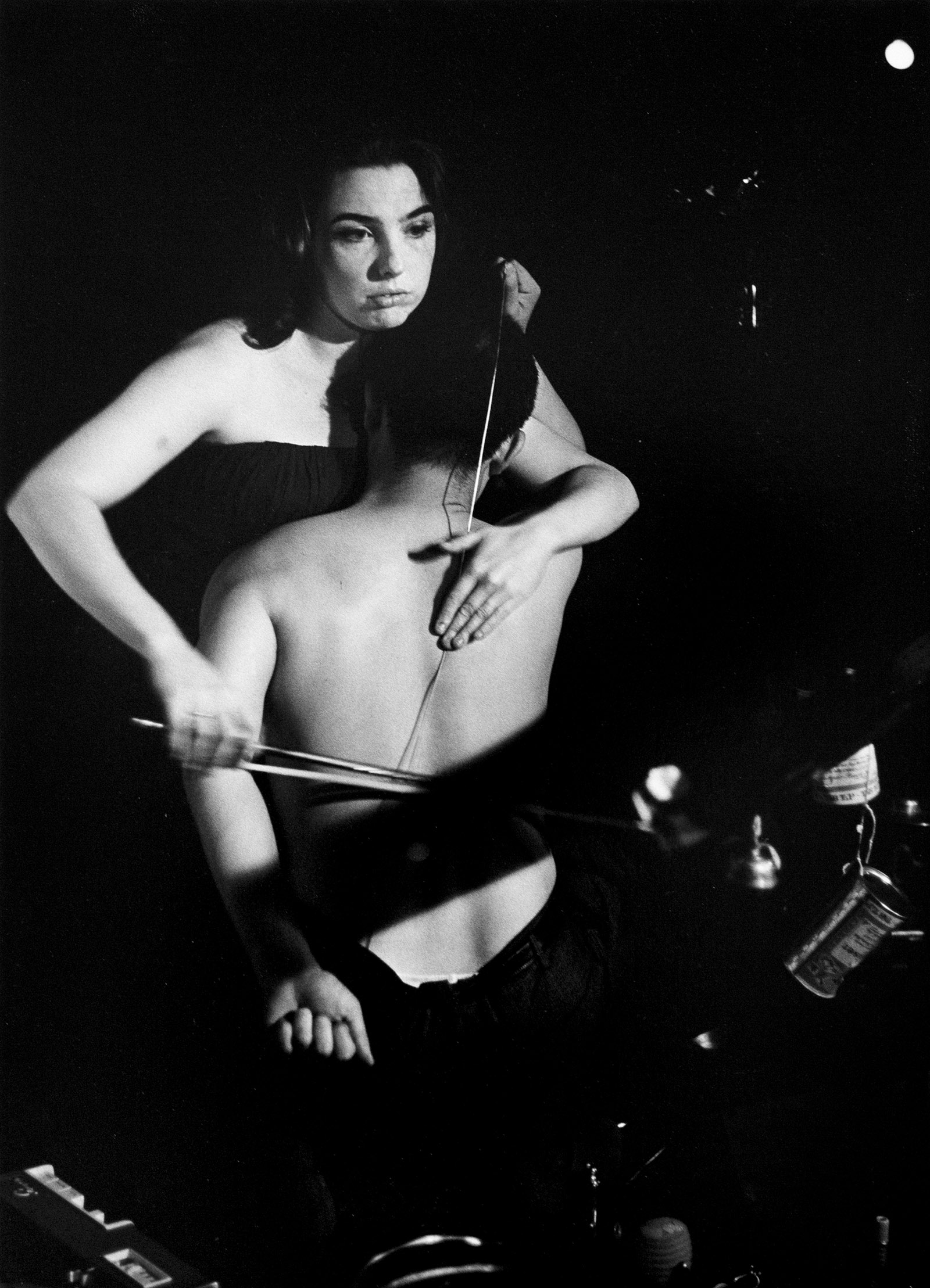

On a freezing night in February 1967, the cellist Charlotte Moorman and the artist-composer Nam June Paik performed Paik’s Opera Sextronique for the first time at the Film-Maker’s Cinematheque, beneath the Wurlitzer Building on West 41st Street in New York City. Undercover cops had lurked at rehearsals, eager for evidence of obscenity. Moorman and Paik delivered: Moorman was often naked (or nearly) during their collaborations. (Paik later said, “It was such a logical and sure-fire idea, that I still wonder why nobody did it before us.”) For the first movement, Opera Sextronique involved Moorman wearing a bra with flashing electric lights, and playing her cello with a violin and a bunch of flowers in place of a bow. For the second movement, Moorman took her top off, and Paik attached toy propellers to her nipples. Before the third movement could start—it was to feature Moorman in a football helmet and jersey but nothing from the waist down—the police rushed the stage, and bundled her and Paik through the snow to jail, where they spent the night. At her trial the judge, Milton Shalleck, declared that the performance was not art, but designed merely to arouse “the vernacular sucker.”

Paik and Moorman had met in 1964, when the Korean-born Paik moved from Germany to New York. Moorman was running the annual New York Avant Garde Festival, as she did most years until 1980. In the early 1960s Paik began making works that involved performers’ bodies. In Amsterdam in 1962 the artist Alison Knowles was instructed by Paik’s score for Serenade for Alison to “take off a pair of violet panties, and pull them over the head of a snob”—Knowles performed the piece twice, before deciding such objectifying antics were not for her. By all accounts, Moorman was a more enthusiastic accomplice. A cello player and former beauty queen from Little Rock whose classical career had not panned out, she became instead an interpreter and champion of the new experimental music. Moorman was collaborator, prop, and medium in Paik’s antic art: she strapped small monitors to her breasts for his TV Bra and played “cellos” made of full-size TVs or ice. In some works, she “played” a large replica bomb. At the Philadelphia premiere of Paik’s Variations on a Theme by Saint-Saëns, Moorman accidentally hit her head on a water-filled oil drum, which she climbed in and out of as part of the performance, and carried on playing, with blood pouring down her face.

To what degree did such performances exploit Paik’s female collaborators? This is surely a pressing question for viewers coming to the work today, though it is not one that seriously troubles the interpretative material in the comprehensive Paik exhibition currently at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam or the accompanying catalog. (I saw the show late last year, in its first version at Tate Modern in London.) In the latter’s most substantial treatment of Moorman, we’re told by the curator Rachel Jans, Paik in 1964 “was searching for a female musical collaborator.” It seems clear that he thought it important to work with a woman at a time when neither the classical nor the avant-garde musical worlds were open or equal. It is worth noting that Paik sometimes visited physical indignities on himself and on other men in performance.

But when it comes to Moorman’s nudity, and all the rest (the bras, the sexually performative histrionics), his motivations and attitudes seem unreflective: he hoped, he said, to “stimulate” the audience, including sexually. As Jans points out, when it came to the forms such stimulation might take, Moorman “shouldered the burden of their consequences” in the form of scandal and notoriety. Opinions differ as to how knowingly she did so. Knowles was happy to work with Paik in other performances, but also said of her friend Moorman:

She was always this girl from Arkansas, this wonderful child in a dress, holding flowers—so when someone tells her to take off her clothes, she takes off her clothes, and when someone tells her to go naked into the water, she’ll do it.

Carolee Schneeman, also a friend, saw the nude performances of the decade as a precursor of her own more obviously feminist art of the 1970s: “I completely identify with her use of the body because it was absolutely playing against the anticipated eroticism of the time,” she said. Schneeman even regarded Moorman as a performer who at times eclipsed Paik: “He was almost like her acolyte.”

Moorman died of breast cancer in 1991, and Paik devoted an installation, Charlotte Moorman Room, to her memory. There is a version of it, hung with clothes she wore onstage and off, in the exhibition. Nearby are other artworks and artifacts from the Paik-Moorman nexus, and this is perhaps the point in the exhibition where you get the keenest sense of what an impish (perhaps exhausting) presence Paik could be. In a video of Moorman playing his Variations, she is wearing a bra made of green-screen discs, on which are superimposed images of the performance itself as it is happening. When Moorman emerges from the oil drum, dripping wet, Paik fusses about, adjusting the bra, then vanishes out of the frame. Moorman is a laconic delight in this and other videos: exactingly devoted to the rigors of her role (keeping the cello dry is a feat) and at the same time quite aware of its absurdities and dangers: “We’ll all get put in the goddamn jail, you know. It’s true, we will!”

Advertisement

The serious games of Moorman and Paik did not always endear them to their colleagues in the avant-garde, who, if not more austerely minded, at least liked to be in control of the wilder elements in their work. The artist and the cellist were enthusiastic interpreters of John Cage, who sometimes objected to the extramusical, near-slapstick movements and materials they added to his compositions. “I was determined to think twice before attending another performance by Nam June Paik,” Cage recalled of a 1960 performance, during which Paik jumped into the audience and cut off Cage’s necktie. Jasper Johns wrote to Cage in 1964, “C. Moorman should be kept off the stage.” For Paik, however, his collaboration with “the topless cellist” (as Moorman predictably and unhappily became known) was essential, whatever its trials: “We are like a mythical Greek bird who walked on the ground and if she encountered a largehole [sic] she took wing and flew over it.”

I mention Moorman both because until recently she was a neglected figure—notwithstanding a biography by Joan Rothfuss that was published in 2014—and also because the Moorman room in the current exhibition brings together so many aspects of Paik’s art. He was a musical acolyte of Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen; a presence in the neo-Dada provocations and happenings (Paik always rejected that word) of Fluxus; an artist who considered television to be the object, medium, image, and pure texture of modern life. If Moorman was not exactly instrumental in all of that, she was there for much of it.

Their artistic relationship waned after the 1960s, but among the surprises in the exhibition is Guadalcanal Requiem, a half-hour video piece they made together in 1977. On the island of Guadalcanal in the South Pacific, Paik filmed Moorman, dressed in a GI’s uniform, dragging her cello along the beach and playing it beside the wreckage of an aircraft from World War II. The piece features interviews with American and Japanese veterans who fought between 1942 and 1945, and with Solomon Islanders. In spite of its distorted image, Guadalcanal Requiem is a remarkably direct piece among Paik’s otherwise hyperactive, prankish art—and a rare historical perspective from an artist whose work was more often about the future, extravagantly imagined.

Nam June Paik was born in Seoul in 1932, while Korea was still occupied by Japan, to a family of wealthy merchants. They fled to Tokyo in 1950, in the middle of the Korean War. At university in Japan, Paik majored in aesthetics; he studied music, literature, and art, and wrote a dissertation on Schoenberg. In 1956 he moved to Munich, where he studied art history and musicology, and was introduced to the work of Cage and Stockhausen through the Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music. Chance (or was it chaos?) and electronics became his main interests; he wrote about Cage for a music journal back in Tokyo. His first notable performance took place the following year, in Düsseldorf. A review of the work, called Hommage à John Cage: Music for Audiotapes and Piano, described the scene: “Paik ran about like a madman, sawed through the piano strings with a kitchen knife and then overturned the whole thing. Pianoforte est morte. The applause was never-ending.”

In his early musical inventions, Paik followed Cage in his use of the prepared piano; there are reconstructions of some of these maimed and amended instruments in the exhibition. While Cage’s additions to, or interventions in, the piano tended to be minimal, sufficient to transform it into a noise-making machine, Paik’s approach was more of the kitchen-sink variety, and a good deal more spectacular. As the critic David Toop recounts in the exhibition catalog, Paik’s assistant Tomas Schmit recalled that Paik was apt to attach to his piano “a doll’s head, a hand siren, a cow horn, a bunch of feathers, barbed wire, spoons, a little tower of pfennig coins stuck together, all sorts of toys, photos, a bra, an accordion, a tin with an aphrodisiac, a record player arm.” Individual keys could be set to turn on a transistor radio, a hot-air fan, a film projector, another siren, or a light switch for the room where the performance was taking place.

Advertisement

Composition, performance, sculpture, environment—it is hard to know, in Paik’s early work, where each of these categories might begin or end. It is this tendency that drew him to the Fluxus movement: at a Fluxus festival in Wiesbaden in 1962, Paik performed Zen for Head, a variation on a composition by La Monte Young that instructed the performer to draw a straight line and follow it. A photograph of Paik’s interpretation shows the artist dressed in a suit and lying face down on a roll of paper, on which he has just traced, with the top of his head, a wavy line of black paint.

Already Paik’s musical experiments had begun to turn into visual experiments. Once again Cage is the model, but also a foil for Paik. The eight-minute Zen for Film (1964) is a cinematic equivalent of Cage’s 4'33''. Whereas the notoriously “silent” composition was in fact filled with environmental sounds and audience noises, Paik’s “blank” film, consisting of nothing but white leader, invites the viewer to sully the empty screen with his or her shadow. (The crowds at Tate Modern obliged, adding also the arms-length shadows of their phones.) Zen for Film manages to be both more austere than 4'33''—it lacks the theatricality of a nonperforming performer—and also emptier, more “boring,” than Andy Warhol’s most vacant films of the mid-1960s: the dreamy, forensic Sleep, the slow plunge into night, and out again, of Empire. But Paik’s film is also sillier than anything by Cage or Warhol, less monumental and more purely, endearingly mischievous.

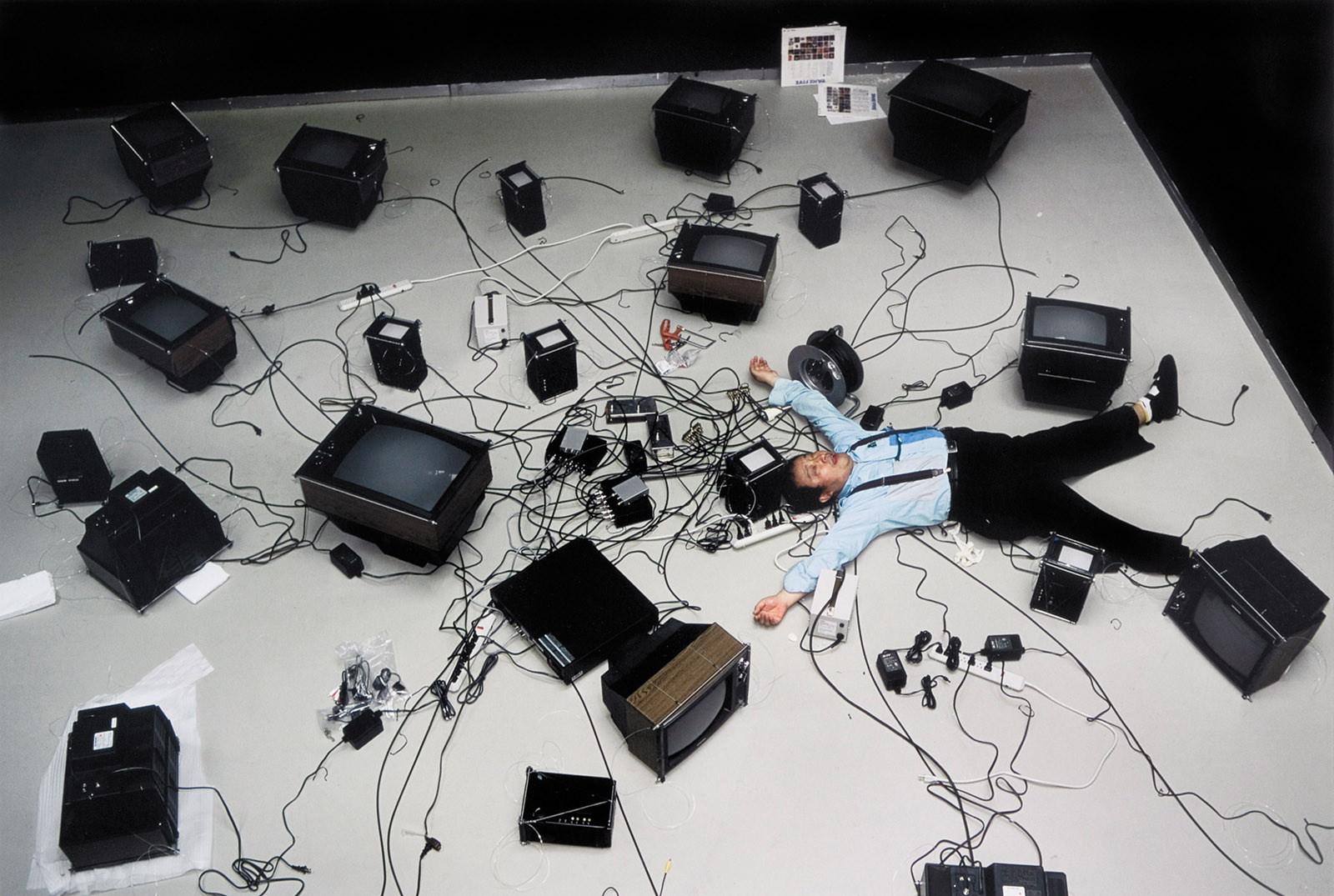

One could say the same about Paik’s works with or for television, which he believed was the artistic medium of the future: “Someday artists will work with capacitors, resistors, & semi-conductors as they work today with brushes, violins, & junk.” His first solo exhibition was in Wuppertal in 1963—Joseph Beuys staged an unauthorized collaboration by smashing up one of Paik’s prepared pianos—and it included thirteen television sets, manipulated to varying extents. Among these is the one featured in Zen for TV, which might be the most elegant work he made in a certain minimal (not yet Minimalist) vein. It seems that two of the televisions delivered to Paik in Wuppertal were defective. One of them he placed face-down on the gallery floor and titled after its brand and model: Rembrandt Automatic. The other set had an interrupted circuit in its cathode-ray tube, resulting in a single horizontal white line on the otherwise dark screen. Paik simply turned the set on its side, so that the line, an electronic horizon, moved from landscape to portrait, from accident or glitch to instant monument. Paik reconstructed this work several times: in the present exhibition, a version from 1990 replaces the original mid-century TV with a subtle black nineteen-inch Samsung that barely distracts from the image. Zen for TV now looks more than ever like a parody of Barnett Newman’s vertical painted “zips.”

Paik is frequently referred to as the first video artist, though the historical details are as fuzzy as the black-and-white image from a Sony Portapak, the (relatively) lightweight camera and recorder that allowed him and other artists of the era to bypass the technical and time commitments of film. Paik is said to have acquired a Portapak the day the system first arrived in the US, and on October 4, 1965, to have recorded the visit of Pope Paul VI to New York, showing his footage to a select audience at the Café au Go Go later the same day. That recording, however, is lost—assuming it ever existed. Warhol is the other major candidate for the slightly meaningless title of first video pioneer: in August 1965 Tape Recording magazine lent him a Norelco camera, recorder, and monitor, the last of which features in Warhol’s portrait of Edie Sedgwick, Outer and Inner Space, filmed in 16 mm the same month. The precise origin or exact definition of video art hardly matters. What does matter is that something had changed, and that Paik had a rather more impure and unruly idea of what such an art might involve than most of his contemporaries, at least in the early days of the medium.

His most celebrated video work is probably TV Buddha, of which there are numerous versions. In a closed loop, a statue of Buddha faces both a video camera and its monitor, so that the figure contemplates its own image, though the pristine reflexivity of the piece is easily interrupted by playful viewers positioning themselves behind the Buddha. With Paik, no matter how neatly recursive the technical array or futuristic the image, there was always in (and around) his video works an element of interference, dirt, and disorder, and a kind of embarrassing eagerness, which slipped easily into comedy. The current exhibition shows a version of TV Buddha from 1974, in which a squat, wooden eighteenth-century sculpture faces a JVC Videosphere TV set, shaped like a space helmet. As with Zen for Film, it is a work that even now, in an age of ubiquitous video, invites a lot of interaction.

Paik seems to have been excited first by the capacity of video to make something attention-getting or wry out of boredom and banality. Among his earlier, Cagean video works is Button Happening (1965), in which for a minute and forty seconds the artist buttons and unbuttons his jacket. But very quickly it was the ability to produce and manipulate visual distortion that proved most thrilling for him. It’s already evident in Magnet TV, also from 1965: a large horseshoe-shaped magnet on top of a television produces a variety of tortured on-screen abstractions. In the same year, Paik conceived the first version of Nixon, a two-screen work in which magnetic coils attached to TVs or monitors make the face of a speechifying Richard Nixon stretch and roil and grimace. The exhibition includes a 2002 version of this work: from inauguration to resignation, the president is a cartoon monster with intermittent phases of normality.

The magnetic coils and switching mechanisms for Nixon were made by the Japanese engineer Shuya Abe, with whom in 1969 Paik devised the Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer. The machine allowed an artist or filmmaker to manipulate seven image sources, overlaying live footage with colors and effects, all of which were ephemeral, difficult if not impossible to repeat precisely. A version of the synthesizer is in the exhibition—a hulking, scuffed metal cabinet with switches, dials, and knotted patch cables—as well as examples of its warping, solarizing effects. “Is sloppy machine, like me,” Paik said in a 1975 profile in The New Yorker by Calvin Tomkins. By contrast, Paik’s experiments with computer animation, undertaken at Bell Labs in 1966–1967, produced images and textures that were just too clean. Analogue video, with all its irregularities, remained his favored medium.

In time, the video signal or recorded footage was incorporated into more elaborate environments and spectacles. TV Garden (1974) is the best known: a variably scaled installation of lush plants and color monitors showing a disparate program of imagery, including a Stockhausen performance, Nixon again, the Andrews sisters, and a Nigerian dance troupe. The curator Andrea Nische-Krupp writes in the catalog, “We must engage with the space, move around the garden”—which was impossible at Tate Modern, where the room devoted to TV Garden was roped off and only a handful of visitors could view it at a time. Still, it was sufficient to get the impression that for Paik, TV was an ambient presence, nearly decorative in its color and glow. TV Garden is an attempt, Paik said, “to destroy national television”: by reducing its hyperactive messaging to a light source for immersive artworks.

But the more dominant trend in Paik’s work is toward a bristling global vision of imagery and information, a pre-Internet fantasy of pleasurably disrupted connection, a “global groove,” as one of his titles of the early 1970s had it. In a 1974 report for the Rockefeller Foundation titled “Media Planning for the Post Industrial Age,” he lamented that cinema, for all its visual richness, had failed to record great thinkers and artists of its time: Husserl, Freud, Proust, Debussy, Ravel, Joyce, Kandinsky. “Future generations might think that the 30’s was the age of only W.C. Fields and the Marx brothers.” In the face of the commercial vacuity of (American) television, there still remained the potential for TV and video to capture the real cultural energies of what remained of the twentieth century.

Much of Paik’s gallery-based work after TV Garden continues his efforts to immerse viewers in a partially simulated space, but in a cruder register. His later installations are increasingly frenzied (and loud) environments that embody the energetic image overload he felt, or knew, was coming. In time, Paik left the TV screen behind and substituted for it successive generations of video projectors, arranged in complex batteries like wartime searchlights. In 1993, for the German pavilion at the Venice Biennale, he made Sistine Chapel, in which, on the walls and ceiling, an assemblage of forty projected images encloses the viewer, including footage of Moorman, Cage, and Beuys—also Janis Joplin, David Bowie, and the synth-pop pioneer Ryuichi Sakamoto. Sistine Chapel shared the pavilion with Hans Haacke’s installation Germania, for which he had turned the marble floor into rubble that invoked the wreckage of German history. The current reconstruction of Paik’s work, with modern projectors, is less brutal in its physical presence and exhibition setting. Its frenzy of images seems also more obvious in form and effect, and less attuned to the direction that the moving image was headed in the last years of the century, on, for instance, our cell phones.

Among the ambiguous pleasures of Paik’s work of the 1980s and 1990s is a reminder that video and television were still the media to which predictions and fantasies about the teeming future of images were attached—until, abruptly, they were not. The most sheerly engaging of his late works were all made for broadcast TV: a succession of live international collaborations, by satellite, that attempted to embody Paik’s faith in a coming “electronic super highway.” He had first used the phrase in 1974, in “Media Planning for the Post Industrial Society.” “Suppose we connect New York and Los Angeles with a multi-layer of broadband communication networks,” he wrote, “such as domestic satellites, bundles of co-ax cables, and later, the fiber-optics laser beam. The expenses would be as high as a moon landing, but the spinoffs would be more numerous.” Telephone communication would become practically free, access to knowledge would suddenly expand for minorities, commuting would swiftly decline, and the capacity of TV to educate and inform would be released with extraordinary consequences for the arts, entertainment, and the nature of work.

Global Groove (1973) was Paik’s precursor to all this, a video compendium shown on New York’s WNET–TV that began with an excited prediction: “This is a glimpse of a new world when you will be able to switch on every TV channel in the world and TV guides will be as thick as the Manhattan telephone book.”

A limitlessly varied channel-surfing that would somehow also remain endlessly interesting: this is the fantasy Paik tried to enact a decade later with Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, broadcast on New Year’s Day, 1984. Switching between WNET–TV’s New York studio and the Pompidou Center in Paris, Good Morning, Mr. Orwell included performances by Cage, Beuys, Moorman, and Merce Cunningham. It was followed two years later by Bye Bye Kipling, a satellite linkup between New York, Seoul, and Tokyo, featuring Lou Reed, Philip Glass, Keith Haring, and Issey Miyake. There were clumsy international handovers, ill-timed jokes between presenters, and occasional technical glitches, but also some truly affecting performances. In 1988, Paik’s final satellite project, Wrap Around the World, connected twelve countries and included Brazilian carnival dancers, Paik himself in Korean costume, and Bowie performing a glorious, raging version of his song “Look Back in Anger” with the Canadian dance group La La La Human Steps.

The abiding impression, watching these satellite TV works in the current exhibition, is of an endearing innocence, a certain avant-garde jollity that eclipses the techno-utopian tenor of Paik’s own writings and the account of his “visionary” ideas given in the exhibition catalog. As an expression of the texture of media saturation and ubiquity, Paik’s global groove was already rather dated. The 1980s fantasy of watching all TV, all over the world, all the time was a visual conceit of TV channels like CNN and shows like Max Headroom that, trying to look futuristic and frantic, were actually still stuck in the sluggish and territorial pre-Internet present.

Some nostalgia aside—as when Bowie is seen chatting to Sakamoto—the aspect of Paik’s satellite spectacles that seems of a piece with his earlier work is instead their convening of a familiar experimental community, and their subjecting these figures and their images, as he had always done, to various playful antics and distortions. The mood on-screen in 1988 was surely similar to the one in Düsseldorf in 1957, or at a performance of Opera Sextronique a decade later: Paik and his associates pursuing a giddy sense of what might be gotten away with.