The archive can be maddening. Historians encounter interesting people there whose lives appear in mere snippets, spurring curiosity that can never be entirely satiated. Scholars of American slavery are particularly familiar with this phenomenon. The people who could give the best account of day-to-day life before emancipation were the people most directly affected by the institution: the enslaved. Yet the nature of slavery was such that these individuals were, with few exceptions, silenced. The vast majority of them could not write and were thus unable to leave letters; their marriages, unrecognized by law, produced no licenses to be maintained as part of an official record. Owning no property, they produced no deeds, evidence of land transfers, or wills to be probated.

Instead, what can be known of their lives comes from the people who enslaved them—self-interested and unreliable witnesses on the question of the inner lives of the people they held captive. It is those inner lives that many historians would most like to explore and make a part of the historical record. If we could only know and tell those stories, we would learn much about the subtleties of the culture in which they lived. These narratives are the missing pieces of an incomplete puzzle that for too many years historians have treated as solved by focusing on the lives of the people in power who did leave written records.

In fairness to historians, the now decades-long push for a more wide-ranging historiography of slavery has led them to move beyond the methods they normally employ, or may have been trained to employ, in order to piece together what they can to defeat the archives’ silence. The discipline of history is, for the most part, wedded to the documentary record; how scholars engage with it is one way judgments are made about the quality of their work. What did they find? How persuasive are their interpretations of the documents? Is there evidence of moving too far beyond what the record suggests? Most people understand that it is impossible to reproduce the reality of a time passed, no matter how many documents exist about a person or an event. The general aim, however—the expectation—is that the historian will try as hard as he or she can to come as close as possible to reconstructing that reality.

There are, of course, creative ways of knowing about people who did not make written records. Families can keep their ancestors’ histories alive by passing down stories by word of mouth (though oral history is considered most reliable when corroborated by at least some documentary evidence). Archaeology gives insight into material culture that can reveal much about an individual. Excavations at Monticello, for example, have yielded valuable information about Elizabeth Hemings, the matriarch of the Hemings family and the mother of Sally Hemings—not only about the nature of her living space but her possession of consumer goods (including a tea set adorned with Chinese imagery that she most likely bought from traveling peddlers). One instantly imagines the enslaved woman—who knew Thomas Jefferson and all the people most associated with Monticello—in her small cabin at the foot of the mountain drinking tea with her numerous offspring and grandchildren, talking about the strange man who held power over their lives and their strange relationship to him. Though it would be entirely reasonable to assume that such scenes took place, we cannot know for certain. There are limits to how far the historian can go.

What are those limits? Does the lack of certainty mean that no attempt should be made to reconstruct the lives of people who were deliberately forced to the margins in their own time? There is an urgent moral dimension to this question that goes beyond the stories of the enslaved. One can argue that historians have a duty—for the sake of historical writing itself—to look beyond the presentations of people who deliberately forced obscurity upon others and portrayed the oppressed in a way that justified their rule over them. Privileging their documents has historians playing along with a rigged system, producing history that is indelibly marked by prejudice, a form of fantasy written in fact.

Exactly what is to be done, then? How should historians construct a more complete and truthful version of the past? Shall we change our understanding of what constitutes “evidence,” how it is obtained and how it is read? Although literature shows us that there are some persistent themes in human life, we must have a degree of humility when facing the fact that our present-day categories, responses, and feelings cannot be simply grafted onto people of the past. It is the art of history to know which pieces fit and which do not. What threshold of evidence must exist before a valid attempt can be made to rescue individuals from historical erasure?

Advertisement

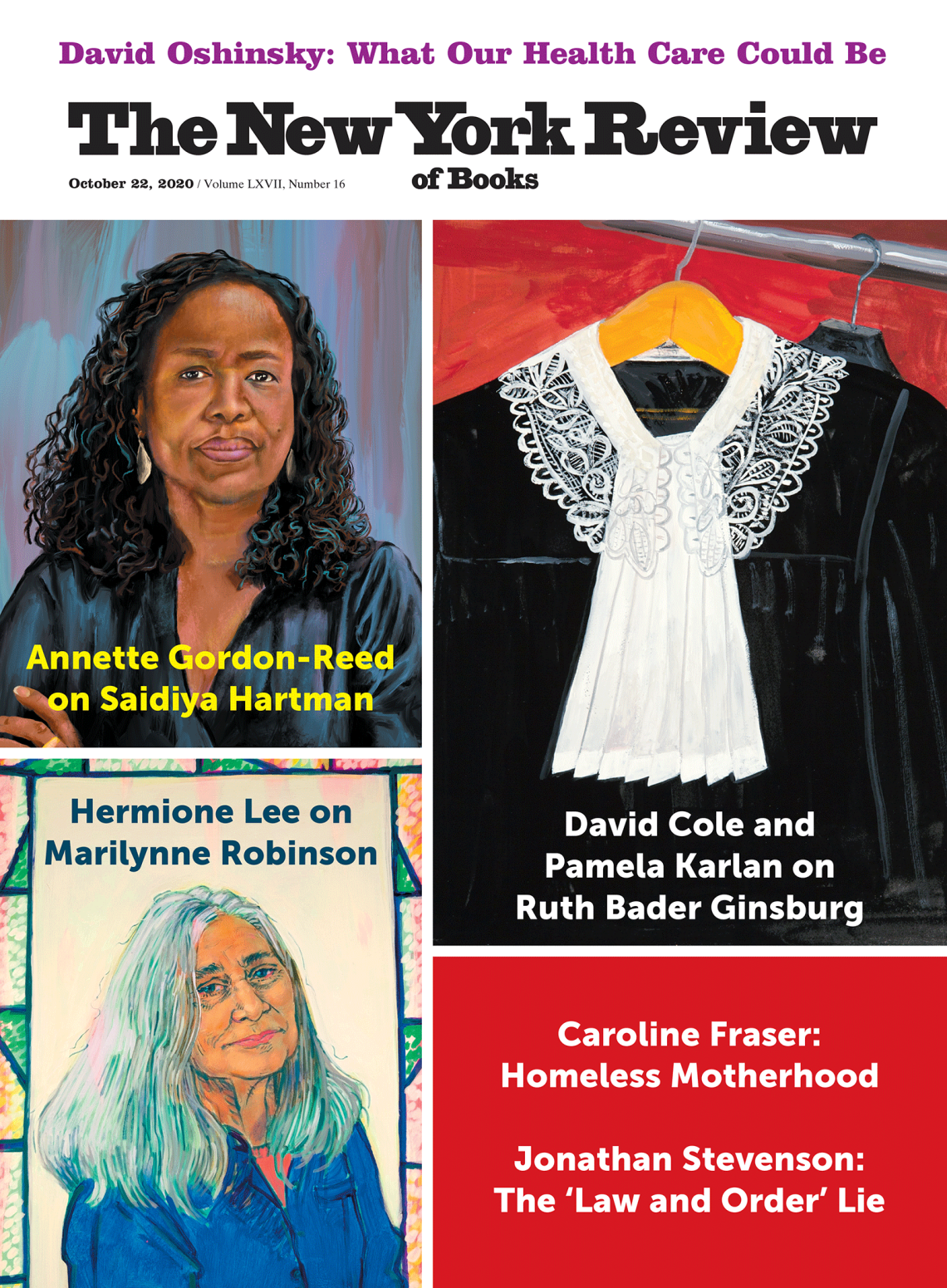

Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments is an attempt to battle erasure, a determined strike against the archives’ purported silence regarding the lives of African-American women living in the direct shadow of slavery. In her “narrative written from nowhere, from the nowhere of the ghetto and the nowhere of utopia,” Hartman seeks to tell stories of young Black women at the turn of the twentieth century who were, she says, in “open rebellion” against the efforts to push them into “new forms of servitude” after Reconstruction. Hartman signals from the very start the extraordinary nature of her project. Opening with “A Note on Method,” she confronts head-on the particular difficulties with what she is attempting to do, and what mechanisms she used to surmount them:

Every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and the authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor. In writing this account of the wayward, I have made use of a vast range of archival materials to represent the everyday experience and restless character of life in the city. I recreate the voices and use the words of these young women when possible and inhabit the intimate dimensions of their lives. The aim is to convey the sensory experience of the city and to capture the rich landscape of black social life. To this end, I employ a mode of close narration, a style which places the voice of narrator and character in inseparable relation, so that the vision, language, and rhythms of the wayward shape and arrange the text. The italicized phrases and lines are utterances from the chorus. The story is told from inside the circle.

By “wayward” Hartman means women who had run afoul of the law or flouted conventional expectations about gender norms and relations. The girls and women whose stories Hartman relates were real people, but she refers to them as “characters,” a choice that further distances the work from what we might called ordinary history, and alerts readers to the fact that more than the usual amount of imagination will be employed in her presentation. In her mind’s eye, the historian tries to see people she doesn’t really know and times in which she is not living. The prompts about how to do this come from the evidence that the historian is able to gather. Hartman’s prompts come from the

journals of rent collectors; surveys and monographs of sociologists; trial transcripts, slum photographs; reports of vice investigators, social workers, and parole officers; interviews with psychiatrists and psychologists; and prison case files.

Although they wielded much less power, the sources who produced the documents upon which Hartman relies can, in some respects, be likened to enslavers viewing the enslaved. Both were self-interested observers, generally heedless of the inner lives of the people over whom they exercised power, and both told stories that justified the power they held. It is not simply that the stories of Hartman’s subjects have been submerged under the weight of their circumstances; it is that, when they do appear in the documentary record, the information found in these sources invariably paints the women and girls in a negative light. They are never portrayed as fully human, as fellow citizens of the republic. Instead, they are presented as mere problems—almost aliens—with which a presumptively fair and just dominant society had to contend. The system that controlled them is seldom cited for how it blighted their lives.

Hartman is, as she says, “obsessed with anonymous figures.” A professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia, she sees her work, which is fueled by justifiably righteous passion, as “redressing the violence of history, crafting a love letter to all those who had been harmed.” That passion fueled her consideration of the Ghanaians caught up in slavery and the institution’s legacies in America in her much-acclaimed 2008 work, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. Hartman’s efforts to tell the history of enslaved and Black Americans seem particularly timely as the United States reckons with the problem of systemic racism and inequality. As many people, historian or not, have asked: How did we get here?

To restore the humanity of her subjects, Hartman tries a different way of handling evidence in order to see their lives. She reimagines their personhood, taking them far away from the hostile judgments of official records that sought to stamp them with one negative assessment after another. I say “reimagine” because the depiction of the women in official records was also a form of imagination, portraits born of contempt for the poor and downtrodden, racist formulations, and repressive attitudes toward women’s work in society.

Advertisement

In Hartman’s “counter-narrative,” her subjects are no longer criminals, bad mothers, or loose women. They are “sexual modernists, free lovers, radicals, and anarchists,” the “ghetto girl[s]” who were the real-life inspiration for white flappers. Hartman characterizes these women as having effected “a revolution before Gatsby.” Wayward Lives, then, is a “chronicle of black radicalism, an aesthetical and riotous history of colored girls and their experiments with freedom.” These “young black women were radical thinkers who tirelessly imagined other ways to live and never failed to consider how the world might be otherwise.”

This is a daring, and often inspiring, way to consider these women’s lives, although one suspects that it applied more to some of the women than others. Using a case file from the New York State Reformatory for Women at Bedford Hills (which remains a women’s prison to this day), Hartman reconstructs the story of Mattie Nelson, who at the age of fifteen traveled from Virginia to New York to escape the depredations of the South. Nelson was sent to Bedford Hills for stealing a neighbor’s underwear from a clothesline. That this minor crime could result in incarceration, such a devastating intervention into a person’s life, grew out of the relentless effort to police the sexuality of Black women. Nelson’s real crime was that she had given birth to two children, by two different men, out of wedlock. Her mother was also living with a man out of wedlock.

The social worker assigned to consider the case determined that Nelson’s home “was a poor environment,” referencing the “immoral conduct” of both Mattie and her mother. Even the neighbor’s decision not to pursue the complaint against Nelson failed to dissuade the social workers from their course. Because neither Nelson nor her mother professed guilt about having sexual relations with men out of wedlock—“I liked doing it,” Nelson was quoted as saying about her relationship with one of her lovers—they were judged depraved. In the officials’ view, sending Nelson to Bedford Hills for three years was decidedly better than letting her stay in her mother’s home. This was far from true. Although the letters Nelson wrote “are missing from the case file,” Hartman uses a letter from her mother to the superintendent of the prison, as well as information from Nelson’s friends among her fellow inmates and from accounts of the notoriously rampant physical abuse of women housed in Bedford, to describe what she may have suffered during her time there.

Just as historians doing conventional history often come to different conclusions about what the material before them is saying, it is possible to have a different take on Mattie Nelson’s story than the one in Wayward Lives. Hartman’s poignant and imaginative depiction of young Mattie’s relationships with Herman Hawkins and Carter Jackson, her two lovers and the fathers of her children, may call to mind not so much a sexual radical out to explode sexual mores as a typical young girl longing for love, stability, and companionship. These things, particularly the last two, had been made difficult for most Black couples since the days of slavery, and Nelson was no exception. In her world, it was the idea of stable and authentic “Black love” that would have been the radical move, a real threat to the notion of white superiority, particularly the cult of white womanhood that had, from the earliest days of African women’s arrival in North America, designated them “un-womanly” and fit for hard work.

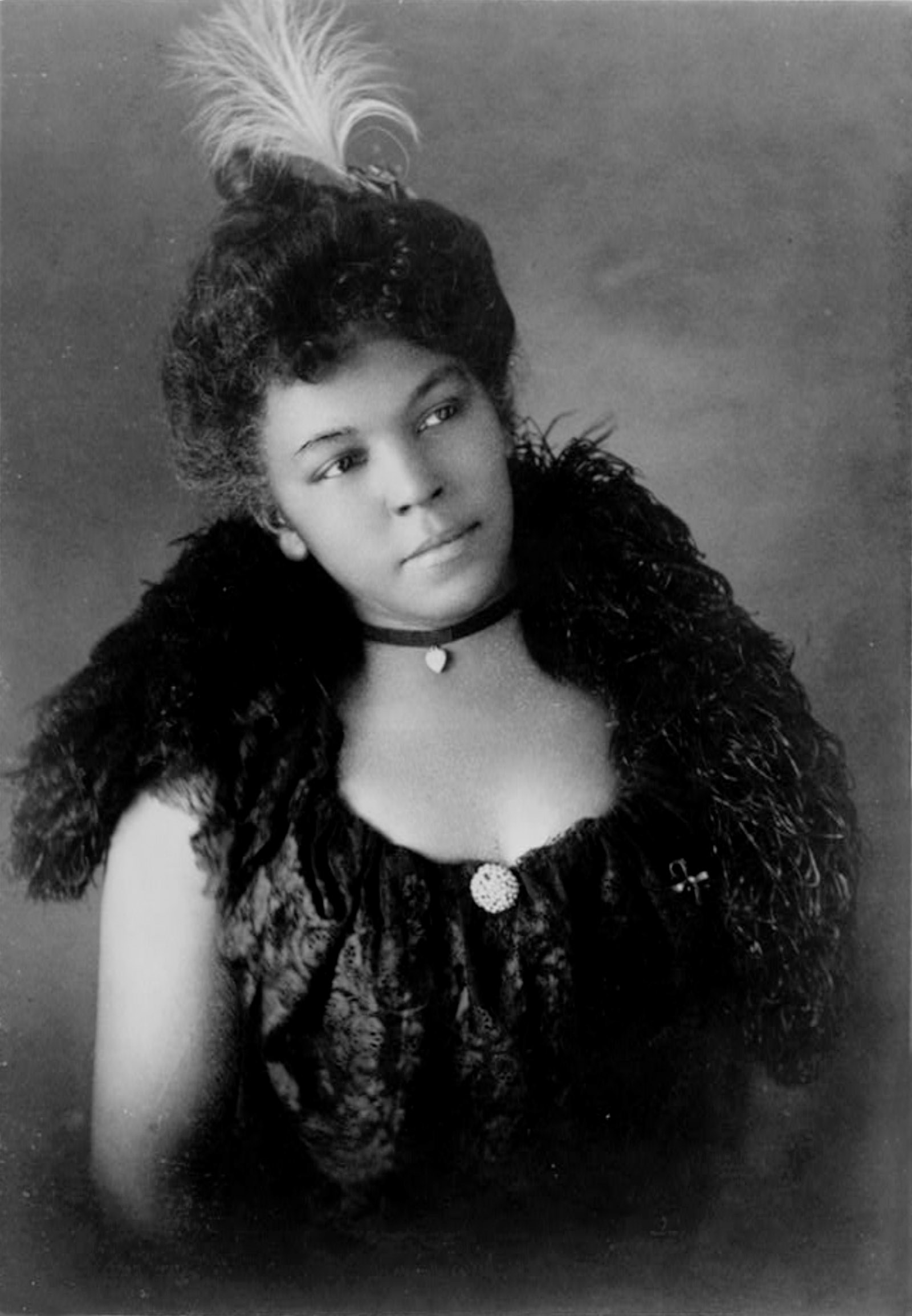

White flappers flouted conventions that, in the guise of protecting them, had limited their horizons. Black women, whether Mattie Nelson or the journalist and activist Ida B. Wells, whose refusal to leave her seat in the ladies’ car of a train on the Chesapeake, Ohio & Southwestern Railroad in 1884 resulted in a physical altercation, had never been “protected” in that way. As Hartman notes, “The very words ‘colored girl’ or ‘Negro woman’ were almost a term of reproach. She was not in vogue. Any homage at the shrine of womanhood drew a line of color, which placed her forever outside its mystic circle.”

What white people thought, however, was not the only thing that mattered. Blacks created their own culture of gender relations that grew out of the circumstances of Black life in the United States. That culture, in the main, accepted that there was a sphere in which men operated and a sphere in which women operated, but made adjustments for the surrounding society’s hostility toward Black men and Black women’s greater participation in work outside the home. The ability to play gender-defined roles within those spheres depended upon one’s access to economic resources.

The country’s decision to put decent employment, respect, and full citizenship beyond the reach of most Black men and women was enormously stressful to Black couples. Nelson, Hawkins, and Jackson had been kept from educational advancement and were forced into a narrow range of employment opportunities, all of them tenuous and, often, detrimental to starting and maintaining marriage and family life. Sex and childbearing outside of marriage, the alleged licentiousness about which the social workers claimed to be shocked, were in part a result of policy choices. Moreover, it was actually what whites expected from Black people. From the days of slavery, Black men and women were said to have merely coupled, as they were moved by lust rather than actual love. Punishing this behavior in the twentieth century, when slavery was no longer legal, was just another means of exercising social control and destabilizing the Black community.

What does all this mean for how we are to imagine Nelson’s inner life? That she had sex with men outside of marriage—and got pregnant in an era of unreliable birth control—does not mean that she necessarily saw herself as a sexual rebel. She was merely acting as a human being in a society that despised people like her and criminalized their behavior. And what of Hawkins and Jackson? Might they have been willing to make real commitments to Nelson if they had steady employment as plumbers, lawyers, or bank managers, or owned successful businesses? If Nelson were given the choice between living a precarious life, depending upon men whom society prevented from realizing their potential, and being a wife and mother under circumstances available to white middle- and upper-class women, there is no reason to assume she would not have opted for the latter. We live after a sustained critique of bourgeois values and lifestyles, decades in the making. Nelson did not. She may have had very different ideas about what it meant to rebel, and what outcome she wished to achieve from rebellion, than we do. We will never know, but Hartman’s sensitive telling of Nelson’s story is illuminating enough without the need to characterize her motives.

Hartman makes clear that American society’s obsession with the sexuality of Black women, again a focus since the days of slavery, set the course of so much of Black life, affecting not just the women themselves, but all who loved and depended upon them. They were constantly at risk of being labeled criminals. “The Tenement House Law,” passed in New York in 1901,

was the chief legal instrument for the surveillance and arrest of young black women as vagrants and prostitutes. The black interior fell squarely within the scope of the police. Plainclothes officers and private investigators monitored private life and domestic space, giving legal force to the notion that the black household was the locus of crime, pathology, and sexual deviance.

Hartman notes that this measure was put in place by “Progressive reformers, official friends of the Negro, and the sons and daughters of abolitionists intent on protecting the poor and lessening the brutal effects of capitalism.” The effort “to protect” people from the “decrepit and uninhabitable conditions” of the tenements was also seen as a crime-fighting measure, as crowded conditions were said to promote criminality and sexual license.

The law did not solve the problem of poor living conditions for many, because building codes were not enforced and landlords were not punished for failing to maintain their properties. It did, however, “consolidate the meaning of prostitution, and suture blackness and criminality, by placing black domestic life under surveillance.” As time wore on it was made even easier to arrest Black women on just the “suspicion of prostitution.” The mere “willingness to have sex or engage in ‘lewdness’ or appearing likely to do so was sufficient for prosecution.”

Naturally, on its face, this law did not just apply to Black women. But the suturing of “blackness and criminality” was a long-standing practice, reaching back into slavery when Blacks were accused of stealing from their enslavers, and after the Civil War when southern whites sought to regain the physical control over Blacks they had had during slavery. The tendency to overpolice Black communities meant that measures like the Tenement House Law had a disparate impact on African-Americans. One doubts that police officers were hanging around wealthy white communities asking young white women if they wanted to have sex, and arresting them for prostitution if they said yes, or engaging in “jump raids,” in which plainclothes police officers,

having identified a suspicious person and place, knocked at the door of a private residence, and when it opened…forced their way across the threshold or…followed behind a woman as she entered her apartment.

These raids were conducted without the protection of warrants, driving home the second-class citizenship rights of those whose homes were invaded by the government.

Not all of Hartman’s subjects in Wayward Lives are unknown. Besides Ida B. Wells, Jackie “Moms” Mabley and Billie Holiday make appearances, as does W.E.B. Du Bois, in one of the most brilliant life reconstructions in the book. Du Bois famously went to Philadelphia in 1896 to study the social conditions of Black people in the Seventh Ward, many of them recent escapees from the South. He had gone there at the behest of administrators at the University of Pennsylvania and concerned philanthropists, who had grown alarmed at the rates of crime in Black neighborhoods, thinking the fault lay with the people rather than the policies that limited the capacity of Blacks to participate in society. Du Bois published The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study in 1899, a work that justifies his designation as the father of American sociology.

Hartman introduces Du Bois by imagining his thoughts while “lingering at the corner of Seventh and Lombard,” taking in “the beautiful anarchy” of the space. We see the newly married young man in his “sparsely furnished one-room flat in the worst section of the Seventh Ward.” In contrast to most of the other subjects in this book, Hartman had a mountain of information—Du Bois’s own voluminous writings (autobiographical and not) and David Levering Lewis’s multivolume, award-winning biography among them—to draw on for an imaginative portrait of the man. There is much less chance, unlike with Mattie Nelson, for misinterpreting his motivations. Hartman’s presentation of Du Bois’s thoughts and feelings rings entirely true.

Du Bois lived to be ninety-five, and his positions changed over the course of his long life. Hartman captures the young, Victorian, patriarchal Du Bois, who though sympathetic could be severely judgmental of the lifestyles of the Seventh Ward’s disproportionately young Black residents, particularly the “wayward” women of Hartman’s formulation. He fought back against that impulse, she writes:

His views wavered, as the heart-quality of fairness, the heartbreak of shared sentiment, overtook the cold statistician. A betrayed girl-mother abandoned by her lover might embody all the ruin and shame of slavery and also represent all that was good and natural about womanhood. Du Bois equivocated regarding sexual freedom and decades later he came close to endorsing free love when it coincided with maternal desire…. In a novel, he possessed the ability to transform a ruined girl who grew up in a brothel into a heroine, but achieving the same in a sociological study proved nearly impossible. Literature was better able to grapple with the role of chance in human action and to illuminate the possibility and the promise of the errant path.

This passage brings us back to Hartman’s book, and the question that lingers over its pages: Why a book of nonfiction and not a novel? Hartman is a tremendously gifted writer with the eye and the lyrical prose of a novelist. A historical novel, using the extensive research she brought to bear in this book, might be just as true and powerful as this work of speculative nonfiction. There would be no need for a note on methodology to justify what she was attempting to do with the work. (Interestingly enough, Wayward Lives won a 2019 National Book Critics Circle Award in the category of “Criticism,” perhaps indicating some difficulty in classifying it.) If her “characters” were approached as fiction, Mattie Nelson could be whatever Hartman wanted her to be, without any nagging concern about whether she had accurately captured the thoughts and feelings of a person who actually lived and had her own story. There is some irony here. Hartman’s method works best with a person about whom much is known, like Du Bois or Wells. The blanks to be filled in about such people’s lives are often just as important, but not so large.

Of course, people should write the books they want to write. Hartman has stated sound reasons for writing Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments in the way she chose. There is the important work of “redressing the violence of history,” and considering the lives of “the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved.” The task of bringing their stories to light is a delicate one, and there is no precise alchemy to it. The talent to do what Hartman does in this book is rare. Fortunately for the women in Wayward Lives, she possesses that talent in abundance, and it is on full display.