One lazy afternoon a few years ago, a woman my age was giving me acupuncture. We were talking about our childhoods and how America used to represent everything that was good and enviable. “You know, folks around me used to say it doesn’t snow in America,” she said, laughing. She was from Yamagata, part of the famous “snow country” of northern Japan. I joined her in laughing, remembering those innocent days.

When World War II ended, nearly everyone on earth, including Americans themselves, admired America. So did the Japanese. We now know, of course, that the Allied occupation forces meticulously controlled the media so that no criticism saw the light of day; the nation was to repent and welcome its defeat. Cynics say the population was brainwashed, and I find myself often agreeing with that assessment. After all, America dropped the A-bomb; the Tokyo Trial was victor’s justice; and so on. Ultimately, however, I have always concluded—if somewhat grudgingly—that the nation’s admiration was justified. America showed generosity toward the defeated; its people wanted a better world for everyone.

Life soon surprised me with the chance to live in America. When I was twelve, my father’s business took me and my family to New York, where we ended up staying for twenty years, from 1963 to 1983. As uprooted children often do, I refused to adapt to my new environment and turned into an antisocial little Japanese patriot. But even during those years of rebellion, at a time when American soldiers were fighting a senseless war in a faraway land and society was in turmoil, I never doubted that the US as a whole was fundamentally a moral nation. Looking back, it seems to me now that my stay there may have coincided with the country’s last best years.

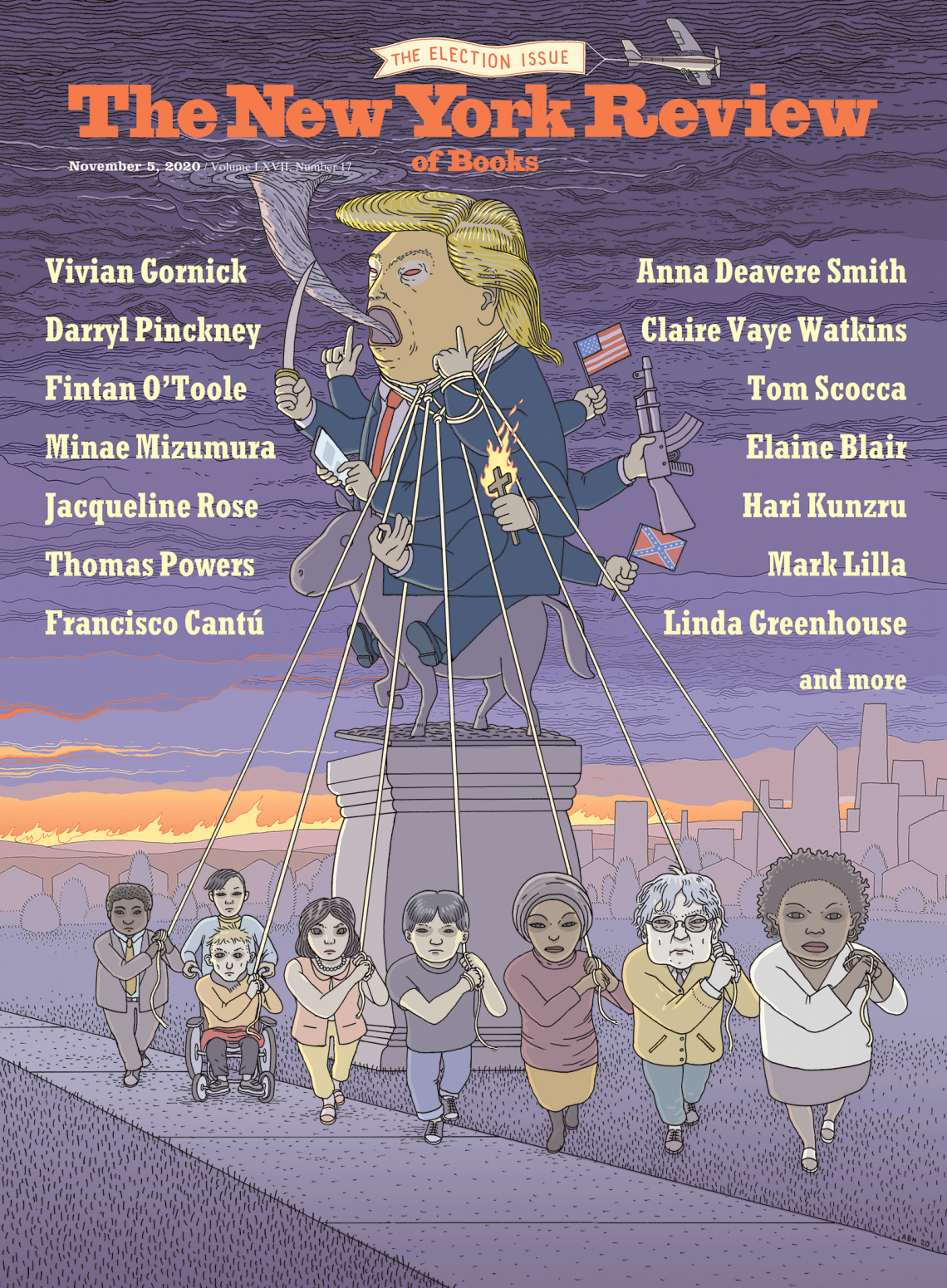

Trust planted in a little girl’s mind stays with her. Yet, following my return to Tokyo, signs kept growing that something was amiss in the US. After a while, those signs began exploding. What? What? I kept saying to myself, bewildered and incredulous. And then came President Trump. I remember the day he was elected. I had to take the bullet train to Kyoto. When I arrived, a newspaper vendor was handing out extras at the station. As I held the sheet in my hand, my mind went numb. Noises around me ceased to exist. My shock was surely no less acute than what my American friends were feeling at that very moment on the other side of the globe, unable to sleep. For the next four years, I felt as if they and I were riding the same roller coaster—a roller coaster that just kept plunging lower and lower. Trump seemed to revel in his amorality. The more he assaulted the human decency that had created America’s praiseworthy institutions and ideals, the more his orange face glowed.

But I am not American. I was not riding the same roller coaster as my American friends. The realization hit me recently when my husband and I were watching a clip of Trump supporters cheering as if possessed. “Poor Americans!” he said. “To think that the whole world is watching this.” I detected something in his voice, and then I knew: what Trump exposed to the rest of the world was not only his unholy self. More to the detriment of the US, what he exposed was the spectacle of Americans making fools of themselves in MAGA rallies, on the streets, and in Congress. Idiotic, hateful, or shamelessly obsequious, they betrayed the image long ingrained in me of America as a nation of big-hearted, fair-minded people. I felt aghast, appalled, even ashamed. Yet I also often felt a bizarre exhilaration—a kind of schadenfreude—on seeing so many Americans brought so low. Ha! Look at you now! I wanted to cry out. And this reaction I could not possibly expect my dear American friends to share.

Yet the gravity of the 2020 US election is such that any schadenfreude of mine is beside the point. Not for one second do I wish Trump to win. Not even for one nanosecond. I believe this is also true of the many people around the world who may harbor, despite themselves, sentiments similar to mine. The world has become so intertwined that we simply cannot afford another four years—or, God forbid, more than that—of Trump wrecking our future, especially now when that future is imperiled by the threat of a renewed arms race and the ever-accelerating warming of our planet—our only planet. I will gladly adore America once again if the country makes a decisive turnabout in November. America doesn’t have to be “great again.” A decent America will be a force to celebrate.