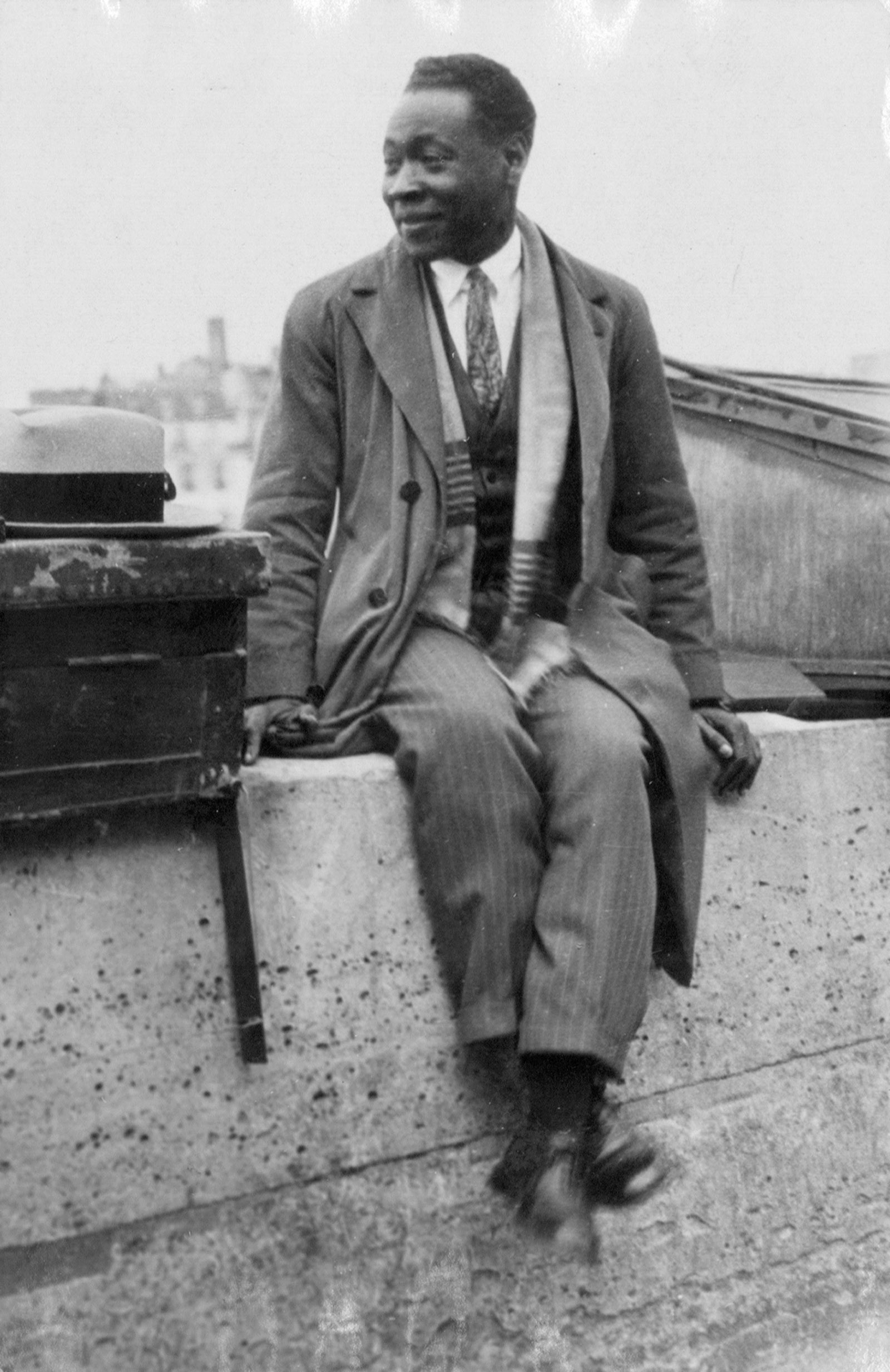

The peripatetic writer Claude McKay was born in Jamaica in 1889 but made in Harlem. As he wrote in his memoir, A Long Way from Home (1937), nothing came close to its “hot syncopated fascination.” His time there was heady and fortuitous. It was a period, recalled Langston Hughes, “when the Negro was in vogue,” and a number of competitors battled for the souls of black folk. They included wealthy, exotic-seeking white voyeurs and Afrophilic benefactors; the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which aimed to marshal the arts into the service of civil rights; the Universal Negro Improvement Association, Marcus Garvey’s pan-Africanist back-to-Africa movement; and the Communists, who, in opposition to Garvey’s “race first” doctrine, argued that the working class, no matter their color, should put “class first.”

These groups prized McKay as someone who might come to personify their ideals. He’d left Jamaica in 1912 to attend the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Shortly afterward he transferred to Kansas State College, then abandoned his studies there, and eventually he made his way to New York in 1914, eking out a living through poorly paid jobs, including as a railroad dining car waiter.

Within a few years of arriving in the “Negro metropolis,” McKay had won many admirers. A sensuous poet and fiery aesthete, he became renowned for “If We Must Die,” his defiant poem written during the violent race riots of 1919, in which whites attacked blacks across the US. Even so, he cast himself as an outsider. Though dismissive of literary politics, he was competitive rather than collegial toward the homegrown luminaries of the inchoate Harlem literary movement. By 1922, the year he published the poetry collection Harlem Shadows, the newly anointed darling of the African-American literati found his fascination with the movement beginning to wane; he felt the need to escape from its vexing limitations, from “the pit of sex and poverty…from the cul-de-sac of self pity…[and] from the suffocating ghetto of color consciousness.”

McKay’s poetic talent had first been spotted when he was a teenager in Jamaica; now he was thirty-two, still dependent on his wits and on patrons whose nurturing hands he’d often threatened to bite. Nevertheless, in the summer of 1922 literary friends passed the hat to provide financing for the notorious ingrate’s next adventure. McKay was bound again for Europe—first to Russia, as a visitor to the Fourth Congress of the Communist International, where he met Leon Trotsky and found himself, to the chagrin of the jealous American delegation, unexpectedly lionized:

The photograph of my black face was everywhere among the highest Soviet rulers…adorning the walls of the city. I was installed in one of the most comfortable and best heated hotels in Moscow.

He spent more than a decade in Europe and Morocco but would not always be so comfortable; his time there was punctuated by ill health and other privations. He was hospitalized and treated for syphilis in Paris. Bordering on penury, he picked up piecemeal work, sometimes as a nude model. He stopped short, though, of debasing himself, rejecting a lucrative offer of a job described in A Long Way from Home as “an occasional attendant in a special bains de vapeur,” or steam bath. He did not spell out what the work might entail but found the thought of it repugnant: “My individual morale was all I possessed. I felt that if I sacrificed it to make a little extra money, I would become personally obscene.” Later, McKay wended his way to Marseille, where he was drawn into a “colored colony” of expat West Indians, African-Americans, and Africans around the Vieux Port. He felt immediately at home:

It was a relief to get to Marseilles, to live among a great gang of black and brown humanity…. [Their] Negroid features and complexions, not exotic, creating curiosity and hostility, but unique and natural to a group. The odors of dark bodies sweating through a day’s hard work, like the odor of stabled horses, were not unpleasant even in a crowded café. It was good to feel the strength and distinction of a group and the assurance of belonging to it.

Marseille was to prove fertile ground for McKay’s creativity. It led, the following year, to his first novel, Home to Harlem. Though it became a best seller, the book caused the revered critic and scholar W.E.B. Du Bois to recoil from its sexual explicitness, writing in The Crisis, “After the dirtier parts of its filth I feel distinctly like taking a bath.”

A decade later McKay’s Marseille sojourn provided models for the characters, and inspired the plot and theme, of what would become Romance in Marseille, a daring work of nostalgia, sex, and violence populated with pimps, prostitutes, and “bistro bandits” (barflies). Had the novel been published in McKay’s lifetime, it would surely have sent the editor of The Crisis back to his bathroom.

Advertisement

Du Bois never had to hold his nose because the manuscript, having undergone several iterations and titles, including The Jungle and the Bottoms and Savage Loving, failed to find a publisher. Even McKay’s agent hesitated to promote a book that he saw would be rejected and considered obscene. McKay reworked, redrafted, and eventually abandoned it in the 1930s. For decades two hand-corrected typescripts languished in archives at Yale University and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. It has now been published by Penguin Classics for the first time, seventy-two years after McKay’s death.

At the start of the novel, in the 1920s, the great drama that will propel the plot and determine the future and fortune of the protagonist has already occurred. In the main ward of a New York hospital, a young African sailor, Lafala, “lay like a sawed-off stump and pondered the loss of his legs.” He’d stowed away on a ship from Marseille to New York; when discovered, he was locked in a freezing water closet; by the time the ship docked, gangrene had set in on his feet. Recovering from the double amputation of his legs, Lafala is resigned to his powerlessness and distracted by welcome dreams of his death, in which he is greeted in heaven by “all the jazz hounds who raised hell in the mighty cities.”

Lafala is something of an enigma. Early on, McKay only offers sketches of the handsome youth, blessed with a “shining blue blackness” and “arresting eyes,” who’d fled Marseille in humiliation after being duped and robbed by a prostitute, Aslima, with whom he’d fallen in love. Other than a reverie of Lafala’s former life in his unnamed African homeland, McKay does not dwell on the psychological trauma visited upon the young stowaway; there are no reflections, for instance, on any post-operative physical discomfort or neurological aftereffects. In the first few short chapters, Lafala is so thinly drawn that McKay risks making him appear merely a cipher for a governing idea of a black everyman subjugated by inhumane and racist corporations. He’s saved from that reductive interpretation through his association with a fellow patient called Black Angel, the only other black man in the hospital.

Black Angel introduces Lafala to the idea of restorative justice, engaging a lawyer to take up Lafala’s case and to sue the shipping company for the inhuman treatment and consequent harm that have left him without his legs. If he can’t walk again, he can at least be compensated sufficiently to purchase a pair of replacement cork limbs. Despite callously suggesting that Lafala must have had some underlying condition that accounted for the gangrene, the shipping company eventually makes an out-of-court settlement. The young African becomes a cause célèbre, and black American newspapers, intrigued by the particularities of his case, boldly lead with the premature headline: “AFRICAN LEGS BRING ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND DOLLARS.”

McKay didn’t have to dig deeply to conjure such a storyline. He needed only to sit and listen to a Nigerian stowaway he met in France, Nelson Simeon Dede, who was similarly abused by a shipping line (the Fabre Company) and suffered frostbite. He, too, successfully sued the company when his legs were amputated below the knee.

Romance in Marseille is a pitiful tale, but McKay said his intention was not to write “a sentimental story.” He succeeded. The shipping line’s amorality is embodied in the official sent to deal with Lafala. His eyes are “full of the contempt of the aristocrat,” and he has a voice that is “cold, smooth and timbreful like tempered old steel.” His maneuvering to deny Lafala’s cunning lawyer his extortionate fee is motivated by financial priorities, not altruism. The corporation’s indifference to the amputee’s suffering is stark, reflecting the attitude of the ship’s captain; a white stowaway would not have been treated so harshly. Lafala was a despised African who crossed the Atlantic locked away in inhuman conditions that echoed those of enslaved Africans during the Middle Passage whose bodies were plundered without fear of censure or demand for reparations.

Lafala, though, notwithstanding the compromises to his mobility, quickly adjusts to the luxuries afforded by the compensation he receives. Buoyed by his new wealth, he decides to return to Marseille, now traveling first class at the shipping line’s expense:

And like all vain humanity who love to revisit the scenes of their sufferings and defeats after they have conquered their world, Lafala (even though his was a Pyrrhic victory) had been hankering all along for the caves and dens of Marseille with the desire to show himself there again as a personage and especially to Aslima.

He’s determined to win over Aslima and thereby to exact his revenge. The previously ridiculed and spurned young sailor returns a new man, propped up on expensive artificial limbs, dressed like an English gentleman, wielding an elegant cane. As might be expected, his newfound riches cast him in a favorable light among the habitués in the drinking dens of the Vieux Port, as well as the prostitutes.

Advertisement

Lafala’s company is coveted immediately both by Aslima (also known as the Tigress) and La Fleur, her popular rival. They’re both formidable but with contrasting physical characteristics. The Tigress, a “burning brown” exhibitionist who’s “stout and full of an abundance of earthly sap,” is portrayed sympathetically; La Fleur less so. She’s a “new-fangled doll done in dark-brown wax” with the heart of a “cold” “tropical green lizard” whose preference, outside of work, is for her female lover. But neither La Fleur nor Aslima is a match for the naked misogyny, only partially veiled, that they encounter in the colony. Misogyny bolts the men together and trumps any competition between them.

The prose becomes more muscular as Lafala pulls into port. Writing and language that had appeared self-conscious and stilted, even a little pedestrian, in the earlier chapters becomes looser and more confident as the novel advances, fired especially by the complexity of Aslima’s character. The monochromatic world of the New York hospital ward gives way to the exuberant Technicolor of Marseille, even if Lafala still seems at times a colorized version of a black-and-white self.

At first he’s dogmatic in his cold stance toward Aslima, having been spurned by her previously, but the Tigress is also a wily temptress, and after withstanding the most perfunctory reprimand from Lafala, she showers him with affection. He attempts to resist her: “He wasn’t going to fall that way like an overripe fruit.” But it’s soon apparent that Lafala’s resolve is shakable.

When aroused by Aslima, his blood is “warm with carnal sweetness.” He’s not alone. Her strange allure among the drifters of the Vieux Port is nearly universal. Though we’re told on one occasion that her impromptu flamenco-inflected dancing approximates a pig squealing in the rain, she transfixes her audience. To shouts of “bravo” and applause from the bar crowd, “she struck an attitude as if she were on all fours and tossing her head from side to side and shaking her hips, like an excited pig flicking and trying to bite its own tail.” Indeed, Aslima later offers her body to Lafala to do anything he’d like with, even descend literally and metaphorically into the gutter with her to luxuriate in mud and filth like pigs.

McKay was determined to write the unfettered truth, as he saw it: “I make my Negro characters yarn and backbite and fuck like people the world over.” In Romance in Marseille he revels in conveying the quayside’s hedonistic and bacchanalian spirit. McKay’s own experiences of the city—“sometimes [I was] approached and offered a considerable remuneration to act as a guide or procurer or [to] do other sordid things”—informed his depiction, especially of the most unsavory characters, the protectors. They’re exemplified by Aslima’s thuggish Corsican pimp, Titin, whose “prematurely caved in” face, “glassy beady eyes and spoonlike mouth” are a physical manifestation of his corruption and the sly intelligence that equips him to understand “the mawkish weaknesses of the hetairai,” or prostitutes.

Marseille’s tough, bawdy, and licentious waterfront is a siren song for Lafala just as it was for the roustabout McKay. It was the kind of world in which he’d been immersed during his time in Harlem and earlier in Jamaica, when he had served briefly as a policeman. He soon realized that he was unsuited to the job, confessing that he turned “a blind eye to what it was my manifest duty to see,” as he recalled in the preface to his poetry collection Constab Ballads (1912):

I had not in me the stuff that goes to the making of a good constable; for I am so constituted that imagination outruns discretion, and it is my misfortune to have a most improper sympathy with wrong-doers.

Lives in the “colored colony” are visceral, and love is the cousin of disgust. McKay captures the tension in the quayside crowd between sexual indulgence and a real, though fragile and hypocritical, code of decency—one that only surfaces rarely, like an archaic law that has long been on the statute books and thought to be outdated. There’s a thin line between what’s considered coarse and what is considered refined, and the temperament of the crowd frequently pivots from bonhomie to sudden violence.

McKay ably depicts the reversals and disappointments that induce a kind of learned helplessness among the seamen, vagabonds, and other formerly itinerant adventurers. They had sufficient energy and chutzpah to leave their homelands but stall on arrival at their destination, never confident enough to move inland from the port, and soon become broken, shipwrecked men awaiting rescue from their stupor through a berth on the next ship.

Late in the novel (here again there are similarities with McKay’s Harlem experience), Lafala is courted by radical left-wing intellectuals. St. Dominique, modeled on McKay’s friend Lamine Senghor, a Senegalese Communist and black nationalist, is a brotherly mentor to the waterfront seamen and a spiritual adviser with ambitions of raising their political consciousness. He detects in Lafala a nascent hunger for a life of meaning beyond endless sexual gratification, which has been evident in Lafala’s intention of marrying Aslima. The idea of marriage is a fantasy that, left unchecked, grows into a grand delusion as the lovers hatch a plan to escape Marseille and return to Africa.

At the same time, there are whispers throughout the colored colony of Aslima’s alleged insincerity—that all along she’s been scheming, embarked on a long con that will culminate in a sting on her lover’s finances. Years of sex work have made her cynical, but McKay also conveys her tenderness as she moves toward the light of her better angels. Who is really being manipulated? Is Aslima actually deceiving her pimp or the amputee? Is Lafala being duplicitous in his promotion of their shared Garveyite back-to-Africa dream? Will he abandon her at the quayside and board the ship alone? McKay keeps us guessing.

Toward the end of Romance in Marseille, the narrator tries to make sense of the magical grip Aslima exerts on Lafala: “Something was always burning, never consuming itself and going out, but always holding him.” It’s a description that also captures the enduring appeal of McKay, the romancer and dreamer who in this novel, unrealized in his lifetime, forges a tender tale, a mounting litany of loss and regret.