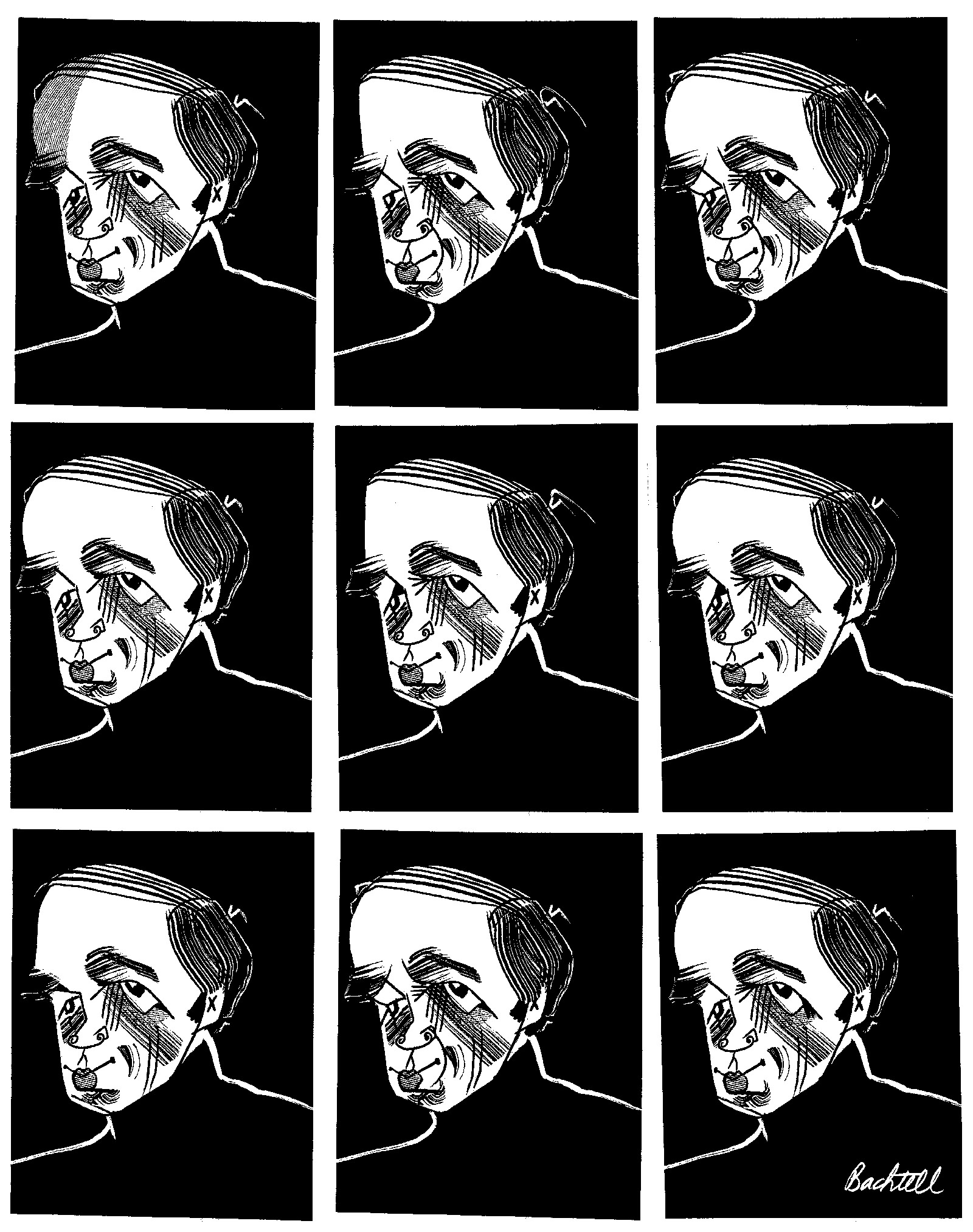

In 2014, when I was an apprentice conductor with the Chicago Symphony, I first conducted that ensemble in public with an enormous projection of Pierre Boulez looming over me. Boulez, the revered and widely influential French composer and conductor, was nearly ninety at the time. He had originally been slated to lead two weeks of programs in Chicago, but his declining health prevented him from traveling; as a result, his conducting duties were apportioned among three young conductors, myself included.

The orchestra’s administration compensated for the disappointment of Boulez’s physical absence through video interviews with the maestro about the music on the program (a colorful medley of works for orchestra and chamber ensemble by Igor Stravinsky and Maurice Ravel), which were projected onto a screen behind the musicians. In between each piece we performed, there was Boulez, fittingly larger than life, reminiscing about the political obstacles to performing German composers’ work in France during World War II or loftily expressing his reservations about the music that the audience was about to hear. This, I remember thinking as his magnified Cheshire-cat smirk hovered above me in the hall’s semi-darkness, is exactly how many composers have felt for the past sixty years.

When conductors manage to continue performing into their eighties, their colleagues tend to soften their views, even of maestros who were once feared and despised. A shock of white hair and a newly tremulous tone of voice in rehearsals has helped many former tyrants come to be seen as benevolent fountains of wisdom. I can think of no other artist for whom this transformation was as complete, or improbable, as Pierre Boulez. When he was a young composer and polemicist in Paris in the 1940s and 1950s (he did not seriously take up conducting until later), he seemed intent on burning down the entire music world, raging even against his former idols and teachers—Arnold Schoenberg, Olivier Messiaen—for their pitiful failure to be absolument moderne. The sheer force of his fury, the bloodthirstiness of his crusades, convinced many of his colleagues that he must surely have been obeying a deep inner logic.

Later in life, Boulez spoke more softly, if not necessarily more kindly. And as he became an ever more respected conductor, a narrative took hold: he had mellowed; he was actually very nice. Given his lingering reputation for Rimbaudian savagery, he was capable of creating a favorable impression simply by walking into a room without biting anyone’s head off.

Music Lessons, the translation of the lectures he gave at the Collège de France between 1976 and 1995, provides English-language readers with the fullest document yet of the mature Boulez’s musical thought: his approach to composition, his analysis of his predecessors’ work, and his attitudes toward many sectors of twentieth-century musical activity. It is an important publication, especially because I believe it casts doubt on the notion that Boulez grew wiser or more generous with age. This book embodies his every paradox: he is both discerning and myopic, clever and needlessly cruel, capable of moments of thrilling clarity as well as long stretches full of bland, arid tautologies. His contradictions are the contradictions of the late-twentieth-century European avant-garde; his narrowness became the narrowness of a generation. As his era recedes, it feels newly possible to take stock of both his strengths and his limitations.

When it comes to Boulez’s music, rather than his rhetoric, I prefer him at his most brutal. His early piece Le Marteau sans maître (1955), a setting of the poetry of René Char, is a scorching, cathartic embodiment of the predicament in which midcentury European modernism found itself tangled. Like the “masterless hammer” of the piece’s title, serial music—that is, music whose harmonic content consists of permutations of a fixed sequence of notes, such as the twelve tones of the chromatic scale—had developed into a practically autonomous mechanism that was capable of leading composers around by the nose. In the piece’s instrumental second movement, the alto flute wanders like a weary nomad above a bone-dry texture consisting of xylorimba, drums, and pizzicato viola, which play a lazily hypnotic groove. It is a sparse, desert-like landscape, with no bass-register cushion for the ear to rest on.

Midway through the movement, the pulse peters out, and the alto flute, with a long exhale of a trill, gives up altogether. In response, the percussion and viola snap to life with a vicious, violent dance that seems to mock the alto flute for its feebleness. This is viscerally thrilling stuff, music that hisses and stings like a cornered scorpion, which is surely how it felt to be a composer in Boulez’s position at the time. I wish I could write a piece as blunt, as pitiless as this one.

Advertisement

Compared to the concentrated fury of Le Marteau, much of Boulez’s later music seems to have softened without sweetening. His forms grew ever more diffuse and his sonic palette more sophisticated, but his harmonic language did not evolve accordingly: though he would not admit it, the “hammer” of the twelve-tone system remained his master to the end. Though there is much to admire in his later pieces, especially their scintillating textural juxtapositions, the music’s apparent complexity often amounts to a supersaturated sameness. Every explosion, every would-be violent gesture, confirms only the inherent lack of dynamism in Boulez’s harmonic materials, their inability to organically grow or change. The result is a paradoxical smoothness: nothing Boulez does can break this music’s abstractedly sophisticated veneer. I enjoy these later pieces, but for a reason that I doubt Boulez would appreciate: I find them relaxing, because I know that nothing will happen in them. Within so blandly undifferentiated a harmonic language, nothing can happen.

One doesn’t have to be a master psychologist to suggest that Boulez’s seething rage against so many of his fellow artists might have been a redirected creative frustration, an inadmissible fear of creative infertility. This frustration, and the many defensive maneuvers it engendered, are on full display in Music Lessons.

In his introduction, the scholar Jean-Jacques Nattiez notes that Boulez, in editing the book’s manuscript, “deliberately excluded…as too specific a whole series of references to particular works and composers.” This may have been a mistake: the book’s strongest sections are those with the most specific subjects, especially those in which Boulez interrogates and celebrates the work of his musical influences. The composers who emerge as his touchstones, the select few whose influence he fundamentally embraces, are the three leading exponents of the so-called Second Viennese School—Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern—as well as one composer who refused enrollment in any “school”: Claude Debussy. Boulez also offers enlightening meditations on Richard Wagner and Gustav Mahler. His writing about these six artists, much like his performances of their music as a conductor, shows him at his best: lucid, incisive, full of a deep-burning intellectual passion.

The two composers with whom Boulez most deeply identifies, for widely divergent reasons, are Webern and Debussy. He admires the ascetically rigorous Webern because he precipitated a necessary crisis. Webern’s music manifests an extreme expressive compression; he felt for a while that “when all twelve notes”—the twelve notes of the chromatic scale—“have gone by, the piece is over.” Each note seems to be an unwriting of the previous one: Webern writes not with a pen but with an eraser. This “absolute desire for non-repetition,” Boulez notes, “leads to a complete impasse.” Yet Webern’s compositional zero hour was also productive: the fundamental conflict between his desire to employ traditional forms (sonata, rondo, etc.) and the nontraditional nature of his harmonic materials led him, in Boulez’s terms, to a “thematic virtuality.” Webern’s music is based not on perceptible themes but on virtual ones, on a Mallarméan “Idea,” such as symmetry, which “can be perceived only through its metamorphoses,” the ghostly elaborations of an absent center.

If there is a tinge of envy to Boulez’s admiration for Webern—as a composer, Boulez lacked Webern’s pithiness—his appreciation of Debussy shows a profound methodological sympathy. He admires Debussy’s rejection of preexisting forms, of pieces whose constituent elements are “taken apart and put back together…like an appliance demonstrated by a traveling salesperson.” Many of Debussy’s works conclude by fading “into the uncertainty from which they were born.” In passages like this, Boulez’s defense of the salient features of Debussy’s music—a sense of constant transition, a “mobile” hierarchy in which secondary material can become primary and vice versa—sounds distinctly like a defense of his own later work.

Boulez is equally illuminating about Wagner and Mahler, two composers whose heart-on-sleeve expressionism might seem at odds with the feline aloofness of the Boulezian demeanor. Boulez’s essential insight about Mahler is structural: Mahler’s themes, by their basic nature (their “source in folklore,” their “triviality”), are inherently unsuitable to conventional symphonic development, and as a result such themes “would slowly go on to bankrupt the formal economy of the symphony.” They are subversive by their very banality.

Boulez also highlights the way that Wagner’s patient, luminous treatment of individual chords influenced twentieth-century thinking about acoustics: the shining A major chord that opens the Lohengrin prelude, and to a still greater extent the E-flat major arpeggios that open Das Rheingold, are revolutionary defamiliarizations of basic harmonic objects. The absence of melody or harmonic development allows us to hear these chords not as prefabricated elements in a vocabulary, but as singular acoustical entities; as Rheingold’s arpeggios accumulate, “one cannot decide whether to focus on the horizontal dimension that generates them or the vertical dimension which is the result of these multiple superimpositions.”

Advertisement

Boulez’s take on Stravinsky, on the other hand, strikes me as a weak misreading. In his eyes, Stravinsky was “highly original” in his earlier pieces, which did not have obvious models—or at least not models that Boulez was familiar with—but his later experiments with extant European idioms, and especially his overtly neoclassical pieces, constitute an unforgivable regression. To my ears, the miracle of Stravinsky is precisely that he is equally inventive in every “style” he tries; he is capable, like Picasso, of liberating and setting alight any material he touches.

But Boulez cannot hear past his knee-jerk aversion to anything resembling functional tonality in the work of a twentieth-century composer. In the spirit of experimentation, Stravinsky was willing to run the risk of sounding innocent or even sentimental—a risk Boulez would never have admitted to his oeuvre’s steel fortress. This reductive attitude, this refusal to listen past Stravinsky’s surfaces and meet the music on its own terms, is a harbinger of the bullying narrow-mindedness that Boulez brings to his analyses of more recent music.

Over the course of Music Lessons, Boulez trains the automatic weapon of his disdain on practically every school of twentieth-century musical thought. He does not reserve his ire, as I expected he might, for composers whom he considers backward-looking; he is equally intolerant of artists who dare to make music using new sound sources (often electronic ones), who experiment with improvisatory practices, or who use unconventional notation. Given the ferocity of these broadsides, it is perhaps merciful that Boulez almost never specifies who or what he’s attacking, but this also makes it impossible to take his criticisms seriously. There is nothing more boring than the spittle-spewing invective of a demagogue railing against ill-defined, possibly illusory enemies, and unfortunately this book seethes with such denunciations. Demoralizing as it is to read Boulez’s bursts of vitriol, it feels important to enumerate them so as to define their scope, which is so vast as to amount to an aesthetic boxing-in. By dismissing past and future alike, Boulez backs himself into a suffocatingly tight corner.

Here he is on the first wave of composers to explore electronic means of sound production:

Rather than asking the fundamental questions…they yielded to the dangerous temptation of the superficial and simple one: is this material capable of meeting my immediate needs? Such spur-of-the-moment and frankly servile choices could not, of course, take us very far.

More recent electronic music, in Boulez’s opinion, seems “amateurish or even incompetent when evaluated as a composition”; such music arises from “a simplistic reflex that precludes the creation of masterpieces,” a “banal and facile exoticism.” As for “recent incarnations of improvisation” (which are not specified), “it is difficult to see any value in them except as individual psychological case studies, or indeed a collective ritual participated in by practitioners of a particular cult.” If improvisation is a dead end, how about music that draws on Classical models? “In this case, procedures are adopted not for their deeper meaning, but as a kind of prosthesis”; the work of neoclassicists amounts to mere “pleasurable dabbling.” And don’t get him started on neo-Romanticism, which “doggedly settled for isolated, bulimic medleys, without any kind of critical distancing.”

What about new methods that seem, on the surface, respectably avant-garde? Pieces that use microtones “clearly do not indicate exceptional imagination” and display a “lack of originality…this new material failed to stimulate genuine reflection on the very compositional practice it posited.” The creation of graphic scores “involved some fetishes of which we can say only that they represented either great naivety or useless cunning.” American Minimalism? Don’t even ask! “One quickly wearies” of their phasing techniques “as soon as one senses how they function.” The use of sonic objets trouvés is a manifestation of “narcissistic cultural play.” If music is inspired by a “chart, graphic, set of instructions or poetic or para-musical text,” then “vanity is its main feature.” Stockhausen-inspired “intuitive music” is of no worth either: “It was soon clear that the musical ideas suggested in this way were clichés.”

Elsewhere, Boulez decries the irresponsibility of certain unspecified reforms to musical notation: “Wanting to change notation without reflecting on the why and wherefore easily turned into a leap in the dark, and attempts at reform were soon forgotten because they were impracticable.” At times, the object of his fury is so vague that it can’t be named; the practitioners of some form of rhythmic experimentation—the use of motor rhythms?—are dismissed as follows:

Even a strong, coherent language, such as that of the best Stravinsky, quickly degenerated into a catalogue of mannerisms…. These rhythmic processes were not integrated into the language in any way, but tacked on as very superficial decoration.

Nowhere in these scorched-earth rhetorical campaigns does Boulez name specific pieces or practitioners, and nowhere does he acknowledge the possibility that he might be trafficking in unhelpful generalizations—or, worse, stomping on a nascent mode of experimentation before it has time to bloom. Like Groucho Marx in Duck Soup, he works himself into a lather over perceived offenses, the origins of which are usually invisible to the reader. Picture all the young composers who attended these lectures over the decades at the Collège de France: How else could they react but by clamming up, doubting their basic impulses, inwardly closing off access to new modes of perception?

An unintentionally comical aspect of the book is that, after pages of rabid assaults on enemies real and imagined, Boulez’s essays tend to conclude anticlimactically, with a kind of shrug. In the last paragraph of “Language, Material and Structure,” he declares that, in the end, “we can but trust our instincts” to perceive the difference between the “musical and the non-musical.” Elsewhere, he says that “between order and chaos”—quite a wide region—“there is room for the most unstable, volatile and rich zones of both imagination and perception.”

Such conclusions, taken in isolation, might strike the reader as broad-minded. In context, however, they are hilariously incongruous: Boulez sounds like a victorious general, standing on a battlefield strewn with the bodies of his enemies, proclaiming the need for peace and reconciliation. Indeed, this pattern—shoot first, shrug later—resembles the larger trajectory of Boulez’s career. In his early years, he was prone to claiming that “all the art of the past must be destroyed”; a couple of decades later, he had blithely cashed in, and spent much of his time conducting cycles of Wagner operas and Mahler symphonies.

This brings us to Boulez’s understanding of “memory”; in his universe, there is no concept more fraught. His writings on memory encompass both “dynamic, creative memory,” employed by individual artists in the acts of composition and performance; and collective, cultural memory, which in his view perpetually risks becoming “static.” One might locate the central struggle of Boulez’s career in the tense negotiation between these two modes of memory. He finds himself continuously drawn, seemingly against his will, to engage with the past (“I do not see how history can be avoided unless by blind fate”), but he exhorts us to stay vigilant, to be sure that if we must engage with our cultural heritage, we do so actively and critically.

Boulez’s examination of the faculty of active memory—the antennae that we all possess but that, for musicians, must be hypersensitive—is among the book’s strongest passages. He defines active memory as a faculty not only of recall, but of presence and prediction: a performer must achieve a “global memory,” which consists of “recall-memory,” “monitoring-memory” (engagement with the present moment), and “prediction-memory.” Boulez compares this multidirectional memory to peripheral vision, without which we could not gain an accurate sense of an object’s position in space. The performer is like an Olympic skier, entirely alive to the present instant, yet also reliant on the momentum of past actions, and constantly scanning for obstacles ahead. Once a musician has fully absorbed a score, “a whole emerges in which memory can roam at will.” The score’s unidirectional temporal canvas becomes, in the hands of a master interpreter, a landscape within which the performer is free to rove, to discover.

If Boulez is at his most penetrating in his analysis of individual memory, he is at his most dishearteningly myopic in his dire warnings against the perils of complacent collective memory. What good does it do, exactly, to shame the nonprofessional music lover for buying multiple recordings of the same piece? Does the act of record collecting really “show in fact a disturbing loss of mental acuity,” and do music aficionados really benefit from being told that their “totemic worship” of recordings “hides an overly superficial grasp of the meaning of a musical text”? To my mind, listeners who are not professional musicians, but whose dedication and inquisitiveness lead them to seek out multiple recordings of a single piece, are an essential part of the musical ecosystem. But Boulez has nothing but scorn for such listeners, and here, as throughout his career, he is notably effective in driving them away.

The book’s baldest self-contradiction lies in Boulez’s contemptuous dismissal of the contemporary phenomenon of “historicism”—a broad term that, in his hands, refers to a sterile or servile fixation on musical history, on precedent and tradition—which is immediately followed by a detailed historical account of past composers’ attitudes toward the past. “Going back a generation,” he says earnestly, “I can already see very different attitudes.” Schoenberg saw himself as part of a continuous tradition; he wouldn’t have given in to mere adoration of the past. Neither would Wagner or Berlioz. Back in the good old days, people lived in the present!

This section’s striking lack of self-awareness made me notice a broader pattern: for all Boulez’s horror of nostalgia, he expends most of his analytical energy on three composers from one historical moment. “Shall I once again sing the praises of amnesia?” he asks grandly at the beginning of his chapter on memory and creativity. Not in this book, he won’t: here he’ll mostly sing the praises of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, whom he refers to—jokingly, but revealingly—as the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Apart from passing nods to Elliott Carter, Luciano Berio, and György Ligeti, the only contemporary composer he regularly references is himself. Where are the celebrations, or interrogations, of his contemporaries—György Kurtág, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Harrison Birtwistle, Sofia Gubaidulina, Luigi Nono, Galina Ustvolskaya, Iannis Xenakis, to say nothing of artists outside the circle of the European avant-garde? Poor Boulez: he contradicts himself, but does not contain multitudes.

The oases that are Boulez’s flashes of insight hardly suffice to combat the pervasive badness of his writing; this collection contains a deadening, stultifying crush of unreadable sentences. There is Boulez as Silicon Valley CEO: “What matters above all is the absolute necessity of global, generally applicable solutions.” There are the sentences that stubbornly resist every effort to follow them:

With respect to material itself, we have seen that the non-musical can either become musical or not, that the salience of the work to this material plays a significant role but is nevertheless not a sufficient condition, and that despite their striking, if passing, qualities, some kinds of material will never be foundational for their musical language, and we are never sure why natural selection yields such-and-such an outcome.

And then there are entire passages that manifest a bottomless, immaculate emptiness:

We can now say that musical forms should be determined according to precise references to an idea exactly determined in all its components, in comparison to much vaguer references to general schemas relating to a common and less individualised background. While certain aspects correspond to relatively anonymous formulas, others very precisely reflect highly individualised characteristics. This depends on the chosen form, and at its heart, those moments that it implies.

I read such passages breathlessly, wondering if Boulez might, God forbid, let some speck of meaning in, but no: their lubricity is total. It’s just like listening to his music.

In a book as long as this one, it is worth considering what is absent. The word “beauty” barely features at all. Boulez typically renders judgment according to the spectra of interest/boredom and order/chaos—two valid but painfully limited frameworks that ignore many of the reasons human beings make music in the first place. Nowhere in the book does he seriously consider other, more organic modes of composition: modes based, for instance, on listening, or on the possibility that the musical materials one works with are not merely dead matter to be manipulated. When I read Thomas Adès’s writings on music, or Morton Feldman’s, I am moved and humbled by the sense that these composers, in their basic practice, are engaging with an otherness that they do not pretend to understand. The goal of Boulez’s engagement with music, by contrast, seems to be pure domination.

Boulez’s universe is also an exclusively male one: each of the more than 110 musicians, scholars, poets, and painters cited in this volume is a man. Only three women’s names appear in the book’s six hundred–plus pages: Cosima Wagner, whose diary is a source for quotations of her husband; the seventeenth-century actress Marie Champmeslé, who makes a cameo when Boulez wonders how Racine might have been declaimed in his own time; and the abstract painter Maria Helena Vieira da Silva. For an artist writing in the last decades of the twentieth century, this is an impressive feat of chauvinism.

As I read, I found myself frequently wondering how Boulez managed to compose at all, given that his basic, unchecked impulse is for impatient dismissal. I can hardly imagine a less receptive, less creative frame of mind. In the end, having blocked access to so many pathways of musical thought, including many that had barely begun to be explored, what does Boulez leave himself with? He traps himself in the historical moment of the Second Viennese School. He works only with the twelve tones of the chromatic scale but refuses to acknowledge the possibility of stability or messy, “unequal” relations among those twelve tones. He builds himself an exquisitely empty glass box and insists on living there. These lectures sometimes feel, as his music sometimes does, like ever more elaborate arabesques around the same arid source: in the Boulezian hall of mirrors, everything sounds like everything else.

In spite of his brilliance and the breadth of his expertise, I cannot help but feel that Boulez was, in the end, more a repressive force than a progressive one. I won’t repeat the crude opening fanfare of Boulez’s famous non-obituary of Schoenberg (“Schoenberg est mort”), but I will say that there is, in this book, precious little that feels really alive.