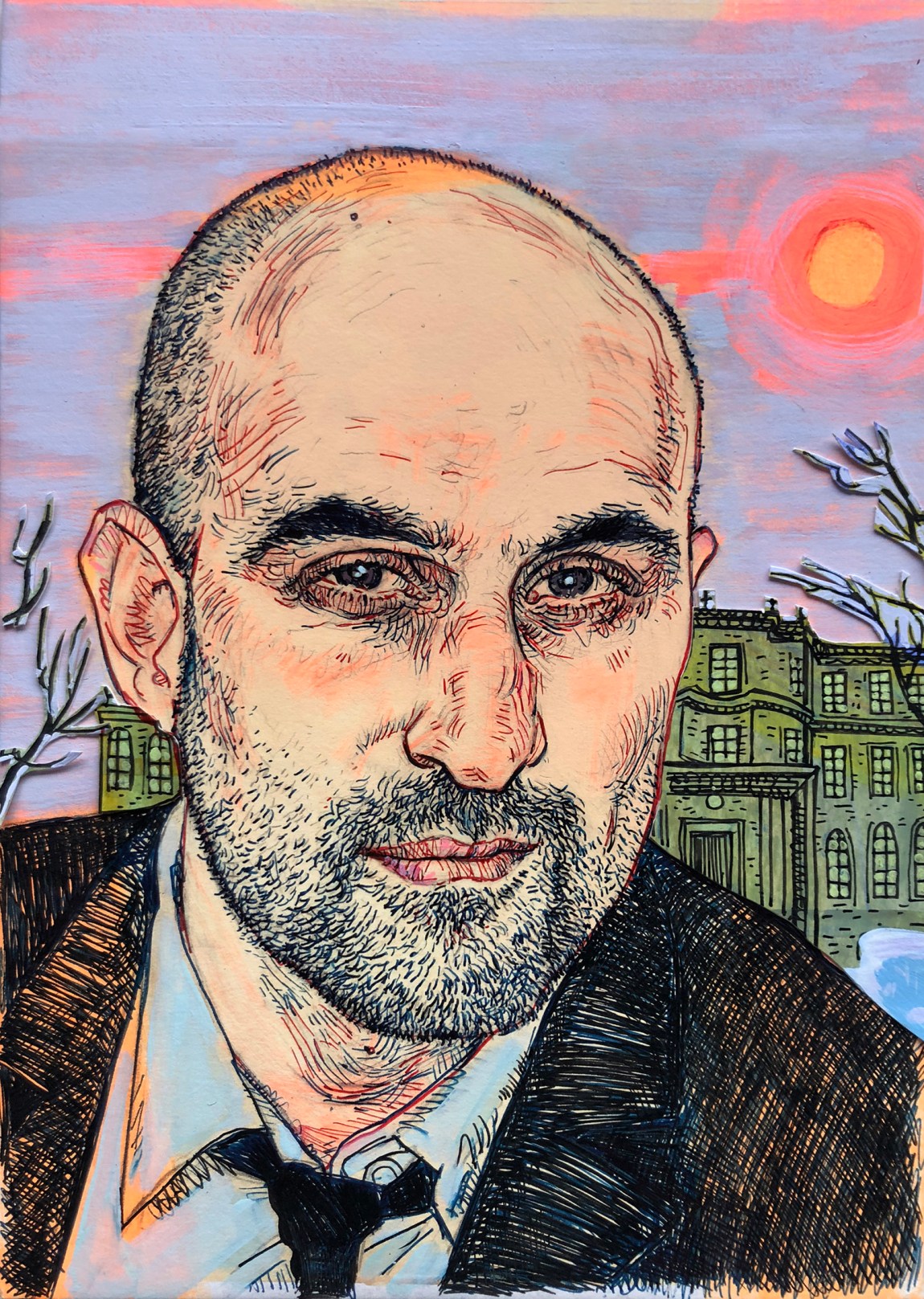

Not long ago, Hari Kunzru was asked in an interview, “What is the worst-case scenario for the future?” He answered with brutal lucidity:

The US becomes an autocracy, and devolves into a weak and fractious patchwork of jurisdictions run by more or less rapacious oligarchs who conduct a losing war with China, first cold then hot. Human rights become a quaint idea. The environment collapses, and the resulting massive migrations of people lead to vicious authoritarian regimes taking control in richer countries. Genocidal wars are fought over water. The Tibetan plateau is a global flashpoint. New pathogens emerge out of the melting permafrost, killing millions. Life becomes hellish for all but the very wealthy. For the masses, the future looks like an insect world of starvation or highly-surveilled shock work; for the few, a melancholy decadence conducted behind high walls. I always thought the shit would go down when I was young and strong. These days I’m just hoping I won’t spend my old age picking through the ruins of my city looking for expired canned food.

As someone who has lingered too long in the doomier corners of the Internet, I felt a strange sense of relief in seeing this dizzying array of potential catastrophes carefully described and cataloged. I was tempted to copy Kunzru’s answer down word for word and keep it in my wallet to be whipped out the next time I heard someone say, “Everything will be OK; all we have to do is get people to the polls!”

The interview turned out to be a fitting preview of the style and concerns that animate Kunzru’s haunting and timely new novel, Red Pill. It takes its title from the film The Matrix, in which a young hacker, known as Neo, expresses his fear that something is amiss in his comfortable world, something he can’t quite put his finger on. He turns to Morpheus, a mysterious figure who has just come into his life, and is offered the choice of two pills, one red and one blue. In Morpheus’s words:

You take the blue pill: the story ends, you wake in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill: you stay in Wonderland, and I show you how deep the rabbit-hole goes. Remember—all I’m offering is the truth, nothing more.

Neo takes the red pill and is shown a much harsher reality than the one he thought he was living in. The only consolation is that he now knows the truth. His eyes have been opened.

“Red-pilling” has become shorthand among neo-Nazis and the far right for the radicalization process. In their conception, taking the red pill means giving up the reassuring illusions of the liberal mindset and embracing the “true nature of reality,” which is ancient and savage. In this world, driven by a supposed struggle for dwindling resources among competing groups, the radicalized scheme to throw everyone who does not belong to their race or religion off the lifeboat. They justify such ruthlessness by claiming they are merely realists.

Kunzru has written extensively about various Internet subcultures in his work as a journalist, including in these pages.* No doubt he could trace the history of red-pilling from its early use as a meme in the creepy Manosphere of pickup artists through its more recent adoption by emboldened neo-Nazis who use it to signal who they think has woken up to the need for a race war. But by choosing it as the title for his novel, he has subtly reclaimed the term. He retains the idea of waking up from a false sense of security into a more conscious understanding of the world, but he refuses to locate this epiphany solely in the domain of right-wing radicalization. The question of what exactly our unhinging narrator is waking up to is the fundamental question of the book and one that supplies its considerable narrative momentum.

Kunzru is not the first to write about the free-floating dread and creeping paranoia brought on by the accelerated technologies and fluid social structures of modern life, but his innovation lies in having grafted a taut psychological thriller onto an old-fashioned systems novel of the sort Don DeLillo or Thomas Pynchon used to write. The effect is dizzying, and also delightful, as he riffs on everything from the early-nineteenth-century German writer Heinrich von Kleist to surveillance culture to the Counter-Enlightenment to the history of schnitzel, while somehow still clocking in at under three hundred pages.

As the novel opens, the unnamed narrator struggles to describe the nature of the midlife crisis that has overtaken him. He lives in a lovely Brooklyn neighborhood with his strikingly competent wife, Rei—a human rights lawyer—and their young daughter, Nina. Like other men his age, he laments his declining strength and power, but not because he fears it will make him less attractive. Instead, his concern is that his decline will make him unable to care for the people he loves. Haunted by pictures of refugees attempting to escape to safer places, he asks himself:

Advertisement

If the world changed, would I be able to protect my family? Could I scale the fence with my little girl on my shoulders? Would I be able to keep hold of my wife’s hand as the rubber boat overturned?

This existential uneasiness is already coursing through him as he sets off for a three-month writing fellowship in Germany, where he hopes to finish a book exploring the construction of the self in lyric poetry, and to find some peace and solitude for himself. It is January 2016 and it still seems possible to escape the steady drumbeat of bad news for a spell. But when he arrives at the Deuter Center in Wannsee, a suburb of Berlin, he quickly realizes that he has miscalculated. There will be no privacy or peace in this place, which turns out to be dedicated to a radical ethos of “openness and transparency” that requires its fellows to work in an open-plan office and have every keystroke they make logged by the center’s system, so that their scholarly productivity (or lack thereof) can be recorded and quantified.

In a series of darkly comic scenes, Kunzru sketches out a dystopia bound to drive an introverted, privacy-conscious writer mad. Besides being monitored for productivity, the narrator is harangued during the communal meals by a pompous neurophilosopher named Edgar, who makes fun of the narrator’s project. Edgar is the sort of hard-nosed philosopher, sometimes known as a physicalist, who argues that consciousness must be explained only as a material phenomenon and that any other explanation is mystical nonsense. He challenges the narrator: Doesn’t he know that consciousness is “essentially epiphenomenal”? (Or, as Gertrude Stein might say, doesn’t he know “there’s no there there”?) The narrator tries to dodge these questions, but Edgar will not relent: “The self! Where is it? Where is it located?”

The narrator, whose own sense of self is becoming increasingly unmoored in this strange place, comes across as less and less reliable as the weeks pass. He manages to escape his dinner interrogations only by withdrawing as much as he can from life at the center. He eats in his room and loses himself in hours of binge-watching a grim police procedural called Blue Lives. The show is about a group of rogue cops who have become as violent and unfeeling as the murderers and drug dealers they chase. Having spent his nights back in Brooklyn doom-scrolling through pictures of refugee children, he finds himself once again drawn into a hopeless and bloody realm, but this time one with no clear morality. He is filled with queasy dread as he watches a scene in which a sadistic cop named Carson, who masquerades off-duty as a sober family man, tortures a man with an electric drill:

Usually I could watch dramatized violence, even convincingly shot and acted, without feeling much beyond a sort of defensive boredom and a mild interest in the plot, but something about this was different. I felt—there is no other way to put it—at risk, as if I were present in the room and there would be consequences for watching. It seemed to me that unless I did something to prevent the torture, I would be mentally and spiritually violated by it, by its imprint, its presence in my memory.

The writing of the show strikes him as informed by a particularly vicious strain of Social Darwinism, and as he whiles away his time watching episodes, its language starts to seep into his own thought. One night after he finally turns it off, he reflects on what he has seen:

People never talk about the insanity of the decision to start a family with everything an adult knows about the world, or about the terrible sensation of risk that descends on a man, I mean a man in particular, a creature used to relative speed and strength and power, when he has children. All at once, you are vulnerable in ways you may never have been before. Before I was a father I’d felt safe. Now I had a child, everything had changed and it seemed to me that safety in the past was no predictor of safety in the future. I was getting older, weaker. Eventually I would fall behind, find myself separated from the pack.

Soon these questions of vulnerability and weakness begin to overtake him. He spends his time going on long walks alone around the lake near the center, not far from the villa where the Nazis once met to plan the Final Solution. In his travels, he crosses paths repeatedly with a refugee father and his young daughter, and wishes he could find a way to help them. Their plight gets muddled in his mind with fears for the safety of his own child, and on calls home to Rei he rants unnervingly about how they must prepare for the unexpected lest they get caught off guard by the dark tides of history. He brings up Walter Benjamin, who waited too long to escape Germany and committed suicide at the Spanish border, believing he would be returned to the Nazi-occupied side. In the narrator’s telling, Benjamin met his fate because he tried to stay home in his study with his beloved books and hoped that the Nazis wouldn’t come for him:

Advertisement

Have you been online lately? I think this is what Weimar Germany must have felt like. The sense that something was coming. We have to expect the unexpected. A Black Swan event. We don’t want to be the ones who hesitated…. Ask yourself honestly, what will happen to people like us if they come to power?

But his unflappable wife is not one for such speculation. She says that she’s headed to a Democratic fundraiser the next night, and polls about the coming presidential election are reassuring. She seems alarmed by the tinge of paranoia that has crept into her husband’s voice, but she does not give in to his mood. “We’re smart people,” she says. “If it comes, we’ll see it coming.”

This conversation, which takes place early in the novel, feels like a skeleton key to everything that happens after it. And an enormous amount happens after it. Yet at this moment, as the narrator talks to Rei on the phone, we are still in the land of the reasonable. It can be hard to remember that land, but Kunzru locates it precisely with the now laughable idea that “smart people” will not be caught off-guard. The narrator, however, has already started to swallow the red pill. The world is not as it seems. He thinks to himself:

The shift was bigger than one candidate, one country. The rising tide of gangsterism felt global. I saw nothing reasonable about what was coming. Nothing reasonable at all.

Rei yawned. I tried to put it as straightforwardly as I could. “I just—I don’t want to spend my last years scavenging for canned goods in the ruins of some large city.”

And here the door slams shut on that moment in time. “Would you listen to yourself?” Rei says.

In the weeks that follow, the narrator’s unraveling picks up speed. He fixates on Monika, the mysteriously furtive housekeeper who cleans his room, and tries to get her to admit that the Deuter Center conducts more sinister forms of surveillance than it says. When she finally agrees to talk to him, he gets much more than he bargained for, a standalone story of how her life as an East German punk and radical was destroyed by the Stasi’s determination to turn her into an informer. Monika’s riveting tale is contained in the second section of Kunzru’s book, aptly titled “Zersetzung (Undermining).”

This word—alternately translated as “attrition” or “corrosion”—describes a series of harassment tactics used by the Stasi, in which the aim was to destabilize and demoralize people opposed to the Communist regime so that they would cease their activism. Techniques could be anything from subtly moving objects inside a person’s home to spreading slanderous rumors to sowing suspicion among their fellow activists that they were secret informants, isolating the target through lies and blackmail until the person felt so alienated and despondent that he or she stopped working for their cause. This retreat was called “shutting off” by the Stasi, and they did not care if it came about because of ideological disillusionment, ill health, mental breakdown, or suicide, all of which were common outcomes of the undermining process.

Monika’s account of how she constantly questioned her own perceptions during those years feels like confirmation to the narrator that he is not paranoid and may in fact be under surveillance by shadowy figures connected to the Deuter Center. Soon he is seeing signs and symbols in everything, menace in every exchange. His premonitions about a black swan event, his rising fears of being watched, his rapidly disintegrating purchase on the idea of an autonomous self—all gather astonishing speed and culminate in a spectacular crack-up in the second half of the novel.

His vertiginous descent gathers force when he meets the creator of Blue Lives, a man called Anton, at a party in Berlin and questions him about the show’s nihilistic vision. Where is it coming from? What are his influences? Why in one of the episodes did he use the words of the eighteenth-century diplomat Joseph-Marie, Comte de Maistre, known primarily for his opposition to the French Revolution and the Enlightenment? The narrator quotes a bit of the chilling passage and wants to know why Anton put these words into the mouth of his character Carson during a graphic torture scene:

You left out the last lines. In the Soirées, Maistre talks about the earth being a sort of sacrificial altar, with every living thing being butchered forever, on and on, until what he calls the consummation of things. That’s where you cut.

Anton deflects the narrator’s questions at first, but by the end of the night it becomes apparent that the narrator was right about the racist undertones in Blue Lives. When he makes his accusation, Anton responds with the equivalent of a smirk and a shrug:

“Your weakness,” he added, turning back to me, “is that you’re always surrounded by people who think just like you. When you meet someone who your silly shame tactics don’t work on, you don’t know how to act. I’m a racist because I want to be with my own kind and you’re a saint because you have a sentimental wish to help other people far away, nice abstract refugees who save you from having to commit to anybody or anything real.”

“I feel sorry for you,” I said. It did not feel like a strong comeback.

The traditional liberal stance, its damning mildness, its toothless threats, proves no match for the virulence of the xenophobia that has launched a thousand wars. The narrator storms out, but Anton’s words get under his skin.

Soon after this moment of destabilization, the novel takes a strange, comic-book swerve. Anton becomes the narrator’s nemesis, the narrator an everyman who must save the world. He obsessively tracks and pursues Anton (aka the self-proclaimed “Magus of the North”) from Berlin to Paris to the moors of Scotland, hoping to secure proof of his neo-Nazi loyalties. He notes the seeming absurdity of his quest while also describing his growing sense that Anton is toying with him, controlling his actions, that he is “living and moving in a matrix entirely designed by him, following a chain of hints and nudges intended to lead me to that place.”

This all feels remarkably prescient at a time when conspiracy theories are swirling through the air. Kunzru cleverly keeps the question of the narrator’s reliability unresolved throughout the whole chase. As his dread and fear reach a fever pitch, we are uneasily forced to choose sides. Is he a madman or a seer? Should we ignore his frantic warnings and be “reasonable” like his wife, or is reason no longer a guiding principle of this world? Where then can we take shelter?

The classic red-pill awakening, whether in art or in life, is one that reveals the supposedly cutthroat, Hobbesian nature of the world. It’s the kind that leads to men in khakis and polo shirts marching through the streets carrying tiki torches and shouting “Blood and Soil” and “You Will Not Replace Us!” It’s the kind that calls for “Don’t Tread on Me” flags and garages full of guns. In the course of this novel, Kunzru’s red-pilled narrator arrives at a clear-eyed but infinitely more generous vision:

It’s not much, but I can say that the most precious part of me isn’t my individuality, my luxurious personhood, but the web of reciprocity in which I live my life…. Alone, we are food for the wolves. That’s how they want us. Isolated. Prey. So we must find each other. We must remember that we do not exist alone.

-

*

See, for example, “For the Lulz,” his review in these pages of Dale Beran’s It Came from Something Awful: How a Toxic Troll Army Accidentally Memed Donald Trump into Office (All Points, 2019), March 26, 2020. ↩