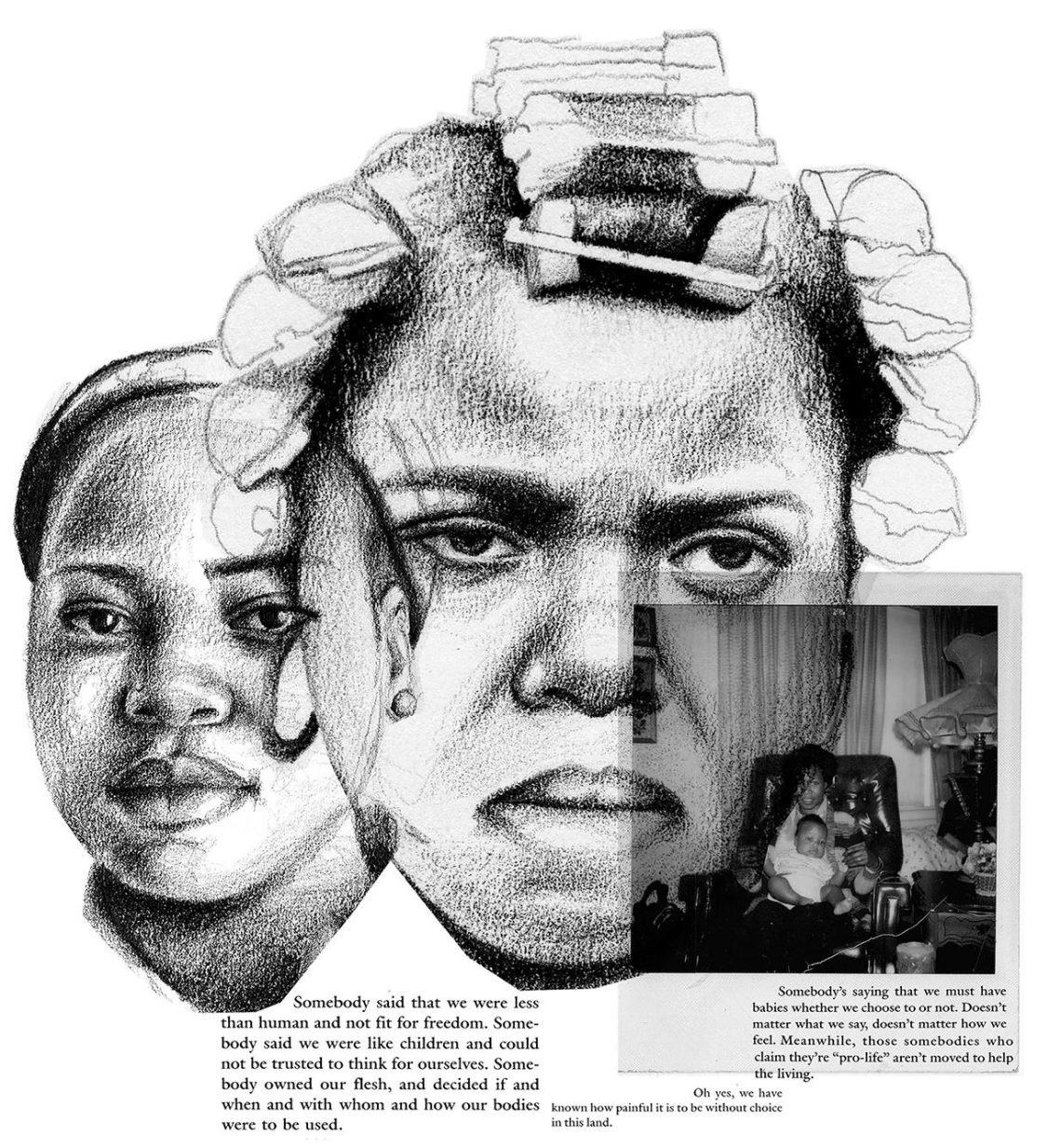

National discussions of abortion—of any services that might end a pregnancy, make contraception available, or provide other means of regulating one’s capacity to bear children—usually focus on the Supreme Court. But for many Americans, Roe v. Wade might as well have been overturned already. Whether RBG or ACB, five conservative justices or six, many American women live in counties without clinics, or cannot afford to pay for an abortion, or do not know how to slip under the limbo bars to get one. Many Americans cannot access basic medical care no matter what decisions they make, but state-level legislation makes abortion in particular nearly impossible to procure in much of the country. Almost four hundred state-level restrictions were proposed in the first half of 2019 alone. This week in Louisiana, voters amended the state constitution to make clear that there is no right to abortion or to abortion funding.

These restrictions have led to clinic closures. At least 275 clinics providing abortion services have shut down since 2013, according to The New York Times. Abortions are not performed in many hospitals and cannot be paid for by federal Medicaid in most cases, further imperiling clinics. An abortion clinic is a money-losing venture. And anti-abortion forces have money on their side.

Four years ago, in what was widely seen as a victory for the abortion rights movement, the Supreme Court in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt overturned a law that made running a clinic in Texas prohibitively expensive by requiring clinics to make costly and unnecessary updates. Yet a year later, Amy Hagstrom Miller, who runs Whole Woman’s Health, had to shut down her clinic in Austin. An anti-abortion organization outbid her for its offices and set up a crisis pregnancy center in its stead. (She was later able to reopen it.) Since then, states have introduced new laws that impose additional restrictions on access to abortion; narrow Supreme Court victories are unlikely to lead to expanded care.

Most troubling of all is a wider criminalization of women’s choices regarding their reproductive health. Our country’s approach to women’s health is marked by a lack of support and an appetite for punishment; jail time over medical care, prosecution over diagnosis. According to Michele Goodwin’s masterful recent study, Policing the Womb: Invisible Women and the Criminalization of Motherhood:

Robust legislating that chips away at reproductive rights and encroaches on women’s reproductive healthcare is about more than abortion. Rather, it is about…the humanity, dignity, and citizenship of girls and women.*

The National Advocates for Pregnant Women (NAPW), a small nonprofit that has led the research and defense of such cases, tabulates that some eight hundred “arrests and equivalent deprivations of liberty” of pregnant women have been made since 2005, for crimes including murder, manslaughter, and feticide. This, they note, is likely a gross underestimate. (In Alabama alone almost five hundred women have been prosecuted for fetal endangerment since 2006, according to an investigation by ProPublica.)

What do such cases look like? For some months now, I’ve been tracking these stories. Take, for example, the case of Anne Bynum, in Monticello, Arkansas. In 2015 Bynum was a single mother with a four-year-old-son. She was arrested upon bringing a stillborn baby to the hospital, after attempting to induce labor at about thirty-three weeks, which she believed would be safe, for a child she hoped to put up for adoption. The local press covered the case extensively. The sheriff suggested the possibility of murder charges.

The timing of the trial is what caught my interest. In the summer of 2016, I had taken a three-week break from working as an assistant at this magazine to fly to El Salvador and report on its mistreatment of women who had had miscarriages. El Salvador is one of six countries in the world where abortion is outlawed. But the country had become so aggressive in what it called the protection of life that much of its legal energy was spent on going after women: either those who had broken the law by aborting their pregnancies or those who had simply, for reasons beyond their control, had miscarriages or stillbirths.

I now realize I could have stayed home: the United States goes after women, too. Our legal system is more and more predisposed against them. As maternal deaths have increased, often due to a combination of poverty and a broken health system—and already maternal mortality here is much higher than in most developed countries, especially among Black women—politicians have enshrined legal protections for fetuses. Nearly a dozen such laws are put forth every year. In Washington State, legislation proposed providing “to unborn children the equal protection of the laws of this state”; in Iowa, bill SF 259 would amend the “definition of person from the moment of conception until natural death under the criminal code.” The government is more and more zealous in its prosecution of women—for having or facilitating access to abortions or simply having a pregnancy loss that deviates from how prosecutors imagine pregnancy to be.

Advertisement

In Anne Bynum’s case, the police became involved after she arrived at the hospital with her stillborn daughter. One nurse testified that alarm bells rang for her because Bynum did not seem emotional, at least not in the way the nurse would have expected. Bynum was questioned at the hospital by a lieutenant from the sheriff’s office and arrested five days later. Two months later, felony charges were filed against her for “concealing a birth” and “abuse of a corpse”—because she had hidden her pregnancy from her mother, who had threatened to kick her and her son out of the trailer in which they lived if she got pregnant and because, in the confusion and exhaustion after delivery, she put her stillborn daughter in a bag and had fallen asleep before getting her son to school and going to the hospital. (The charge of “abuse of a corpse” was dropped after the indictment.) She was tried in the state courthouse in Drew County, Arkansas.

Based on the abstract of the trial submitted to the appellate court, the rules for evidence seemed oddly relaxed; in one instance a Wikipedia page was cited. Expertise seemed politicized: one witness was recognized as having become “a doctor without an ounce of taxpayer money…a doctor with five children in tow.”

Then there was the fact that both the lawyer for the prosecution and the lawyer for the defense regularly mentioned that Bynum had had prior abortions. Bynum’s defense lawyer said, according to an abstract of the trial, that he had vetted his jurors to find out who was “pro-life.” He told them, “That’s the kind of jurors I want cause I think they’re the best. People that value life take the time to determine, look into things, make judgments.”

The jury retired to deliberate at 6:01 PM. At 6:04 PM, they found Bynum guilty and then sentenced her to up to six years in jail. Two years later, represented by NAPW lawyers, her case was overturned on appeal. By that time she had lost custody of her son. She was charged with the cost of his foster care. When she could not pay, her driver’s license was revoked, meaning that she could no longer drive to work.

For many women who are pregnant, any problem or loss that occurs is potentially a criminal act. The targets of fetal endangerment laws were, for decades, Black and brown women; these cases received relatively little press attention. Now, according to Lynn Paltrow, NAPW’s founder and lead lawyer, it is white women who have used drugs who are more likely to be arrested. “Since 2005, the majority arrested have been low-income women, rural white women,” she says, though she adds that Black and brown mothers remain disproportionately targeted in the overall criminal law system.

The standards for these cases often seem subjective and odd, as is the scientific evidence on which they are based. In the case of Latice Fisher, a Black, thirty-two-year-old mother of three who was arrested in Mississippi after having a stillbirth at home in 2017, an autopsy report determined that her baby had been born alive and had died of asphyxiation. The examiner came to this conclusion thanks to a test in which a piece of lung tissue is dropped into water and seen to float or not. If the baby had breathed outside the womb, the tissue would weigh less than that of an unborn child, whose lungs are not yet full of oxygen.

The idea of using floating lungs to test oxygen levels was described in 140 AD by the Roman physician Galen and first used in the United States in 1881 in Texas against a Black woman named Sallie Wallace, who was charged with strangling her son. Even then, as the Northeastern law professor Aziza Ahmed has shown, it was seen as unreliable. In Fisher’s case, the autopsy was delayed for eighty-one hours, possibly changing the structure of the tissue being tested.

State prosecutors charged Fisher with murder—in the words of one court document, with “killing her infant child while in the commission of an act eminently dangerous and evincing a depraved heart.” During the arrest, her cell phone had been taken from her. Prosecutors found that she had researched abortion pills (“Buy abortion pills, mifepristone online, misoprostol online”).

Advertisement

The crux of the case centered on whether the baby had been born alive or not. The case was dismissed last year, and earlier this year a new grand jury voted not to reindict her, but by then Fisher’s face had appeared repeatedly on the local news in connection with the murder charge. She lost her job as a police dispatcher, and with it, her health insurance.

State prosecutors take cues from one another. Currently, a twenty-six-year-old woman named Chelsea Becker is in jail in California. Last September, Becker experienced a stillbirth. The state of California charged her with murder because she had used methamphetamine at some point during her pregnancy. Her defense attorneys made the argument that citing drug use alone ignores all the other reasons why a pregnancy might not come to term. “Increasingly,” wrote Dr. Mishka Terplan of the Friends Research Institute in Baltimore and Dr. Tricia Wright, a practitioner affiliated with the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, in material submitted to the court,

research shows that pregnancy outcomes have far more to do with economic, social and environmental conditions experienced in the course of one’s life, rather than anything one does or does not do while pregnant.

Drug use can cause birth defects, but so can alcohol use (which is not criminally prosecuted in the same way), and so can poverty. So can living in a country that allots so few of its resources to ensuring healthy pregnancies. It does not seem a coincidence that so many of these cases involve women who might not appear “sympathetic” in the eyes of the general public, who might easily be painted as bad mothers, and who lack the resources—both of money and of education—to defend themselves in a legal system predisposed to finding them guilty. “The road to arresting women for having abortions is being paved by the cases involving pregnant women and drug use,” says Paltrow.

Prosecutors cited California penal code 187: “Murder is the unlawful killing of a human being, or a fetus, with malice aforethought.” But Paltrow points out that subsection 3 specifically says that the law “may not be used against the mother of the fetus for anything she solicits or consents to.” The prosecutors in Becker’s case argued, she explained, that this law only applies for those “consenting to a legal abortion.” The implication is that Becker, who took drugs, is a murderer, and so would be any woman in California who had a self-abortion.

Becker’s bail was originally set at $5 million and later reduced to $2 million. (By way of comparison, the bail for Derek Chauvin, the police officer accused of fatally choking George Floyd, was set at $1 million.) She has been held in jail throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. When I talked with her in July, she had just gotten out of “the hole,” as she called it, the solitary cell she was moved to when her case hit the news. The guards, she said, were not wearing masks. She had only a vague sense of the pandemic. “They’ve done a pretty good job of keeping all of that secret.” She is one of the first two women to face murder charges in Kings County, California, for the stillbirths of their fetuses. (The other, Adora Perez, a twenty-nine-year-old woman in Hanford, California, is currently serving eleven years in prison.)

Why California, that liberal paradise? The prosecutor’s brief seems to suggest that one reason to prosecute women is that other states are doing so. It cites South Carolina’s history of criminalizing the use of drugs and notes that “the United States Supreme Court declined to review the South Carolina Supreme Court’s decision.” The implication is that California could do the same. (The California attorney general recently filed an amicus brief supporting Becker’s appeal, claiming that the law was misapplied and misrepresented.)

The last eight months of contagion, illness, and death have forced a public reckoning about the inequalities of health care in this country. Anyone who has spent any time looking at women’s health in the United States would not be surprised. The men who make the laws—and in the cases described, the prosecutors and judges are primarily male—seem to see punishment as their profession and purpose. Punishment for women who have taken control of their bodies, I almost wrote. But were any of these women really in full control of their situations?

In the absence of clinics, or in view of the cost of the procedure, more and more women administer their abortions themselves. Calculating the exact number of women who do so is difficult, but researchers have tracked both an increase in the number of women who say they have induced their own abortions and an uptick in Google searches for abortion pills. The right to abortion is legally protected, but in much of the country pursuing this right on one’s own is not allowed by law. As of 2019, six states have criminalized self-induced abortions; there are nine states in which fetal harm laws “fail to adequately protect pregnant people from criminalization,” according to the abortion-rights advocacy group If/When/How. Fourteen more have laws that can be applied to women who induce their own abortions. Most of these laws are initiated at the state level with majority-Republican legislatures. While Republican lawmakers may say their aim is not to punish women, court records prove the opposite. If/When/How calculates that there have been at least twenty-one arrests of individuals for ending a pregnancy or helping a loved one do so since 2000.

One such woman is Ursula Wing, a Web developer living in New York City. In 2012 Wing described taking an abortion pill. She wrote about it on her blog, “The Macrobiotic Stoner.” In more normal circumstances, she wrote, someone could follow “the typical, recommended, approved, tested, documented blahblahblah method of chemical abortion in the United States”: go to a clinic, get two drugs, and pay $500 for the experience. “$500,” she wrote. “Are you NUTS? I’ve got a mortgage and a kid to take care of.”

“It seems to me that the FDA is making what COULD be an easy, private, inexpensive process, a royal pain in the neck,” she continued. “A woman knows when it’s a good time to have a baby, and when it’s not. And this is of greatest consequence to the ultimate health and happiness of our society, and planet.”

From about 2016, according to an indictment, she started to provide pills to others. “I believe in action, and civil disobedience,” she wrote in a blog post. She set up a site called “My Secret Bodega.” She pretended she was selling jewelry. “Gold electroplate twisted multi-rope collar necklace” was code for “MTP Kit of 1 mifepristone 200 mg pill and 4 misoprostol 200 mg pills.” She imported the drugs from India and sent them around the world, disguising the packages as shipments of jewelry. The pills were hidden in a small panel taped inside a larger envelope. In 2018 a man named Jeffrey Smith in Wisconsin slipped two abortion pills—ordered by him from Wing’s website—into the drink of a woman he had impregnated. He was charged with an attempted first-degree intentional homicide of an unborn child and delivery of unprescribed prescription drugs in Wisconsin.

In February 2019 Wing posted on her blog that FDA agents wearing bullet-proof vests came to the apartment where she lived with her young daughter, her roommate, and her roommate’s son. “I got up and walked through the kids’ room to see a beige and black clad man with a crewcut coming down the stairs,” she continued. “In the movies, people scream at the monsters,” she continued, “but in real life, we get quiet in the face of terror.” As described in the blog post, her roommate took her daughter to school. Wing went to her workplace and told her colleagues she would need to take the rest of the day off. When she returned, she noted that the officers had found “everything they were looking for…the boxes of medication under my desk, and the priority mail envelopes ready to go out, sitting in a tote bag hanging off an open drawer.”

She wondered what her neighbors would think. The FDA agents said they’d been told they were there to investigate a rat infestation. Her daughter asked if she was going to jail. “Agent P told me he didn’t think I was the ‘kingpin,’” she later wrote. “What the hell is that supposed to mean?” She continued:

It’s nearly 2am as I write this, and I’m getting 5-10 emails per day from pregnant women begging me for help. Is this the First World?… What happens when the demands of the few eclipse the needs of the many, in a system that damns more than it saves? Such a system requires lots of enforcement. Surveillance requires enormous manpower, and a police state in which the majority are not in agreement with the rule of law that a few privileged beneficiaries hold dear, consumes too many resources to be sustainable. Can you believe they flew these assholes out from Wisconsin to raid little old me? And put them up in the finest Manhattan hotels, I’m sure.

In March Wing pled guilty to “conspiracy to defraud the United States,” a charge that carries a fine of up to $250,000 and imprisonment of up to five years. She was sentenced in July to two years of probation, a $10,000 fine, as well as $61,753, the sum of the proceeds found to have been illegally obtained, in civil forfeiture. (My reporting on her case comes from court documents. She declined to be interviewed for this article.)

It’s no stretch to imagine a future in which access to abortion is even more limited, and maternal health care so scarce that any miscarriage would invite suspicion of actions made newly criminal. Yet the hardships already affecting American women are disturbing enough, and increasingly commonplace. For every person unjustly arrested in connection with childbirth, there are countless numbers who see their lives otherwise ruined or stolen from them by a legal system that favors the potential of the unborn over the reality of life. As recently as this summer, as states tried to further restrict access to abortion by pointing to the pandemic as a pretext to restrict care, women were still asking for help on Ursula Wing’s eight-year-old blog post about abortion pills:

Can someone email me If they information [sic] on how to get the pill from the states. I Already ordered from a website…however covid might mean I’ll never receive the package in time.

Or as another said, “Does anyone have any extra?? Please I’m desperate!!!!”

—November 4, 2020

-

*

Cambridge University Press, 2020. ↩