Translations of Beowulf are often judged by their first word. “Hwæt,” that enigmatic monosyllable, became a stately “behold” or “lo” in older versions of the epic. Modern poets have used their choice here as a calling card, announcing their intentions with more or less boldness. They have transformed “hwæt” into a firm “listen,” a laid-back “hey,” or a cheery “right!” A little over twenty years ago, Seamus Heaney gave the Old English tale an Irish lilt by beginning it with “so.” In her new rendering of the poem, Maria Dahvana Headley goes him one better and lobs the poem into contemporary slang like a ping pong ball into a red Solo cup: “Bro.”

It is odd that we should spend so much ink on the kickoff. Beowulf is a poem that teaches us not to place too much faith in beginnings. Its own origin is hazy: the author is unknown, and so is its date of composition. Two centuries of often rancorous scholarly debate have managed to pin the poem to the period between 700 and 1000 AD, which is rather like saying that Moby-Dick could have been written by anyone from Alexander Pope to Zadie Smith. Likewise, Beowulf’s heroes tend to emerge from the mists of the past—their formation in myth, folklore, and early chronicles is up for endless discussion. What is certain in Beowulf is how things end.

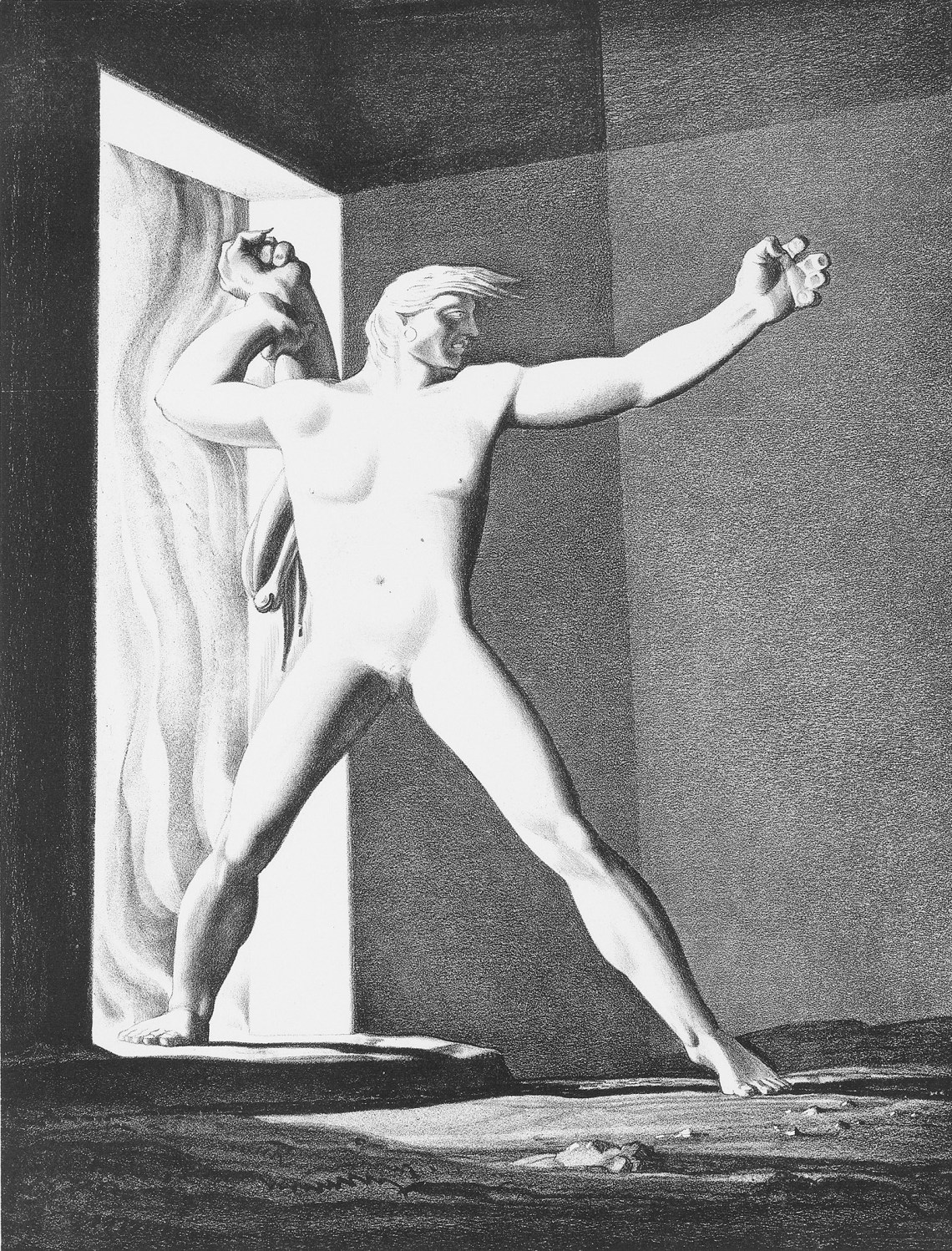

At the start of the poem, the narrator describes the career of Scyld Scefing, a foundling who establishes a kingdom in Denmark and is given a splendid burial at sea. His great-grandson Hrothgar consolidates his power by raising a great hall, Heorot, a place for mead-drinking and gift-giving. The sound of its festivities disturbs Grendel, a monstrous descendant of Cain and prowler of the fens, who launches a series of deadly nighttime attacks on the men sleeping in the hall. Having heard of his depredations, Beowulf sets off with his men from Geatland, in the south of what is now Sweden. An orphan with something to prove, Beowulf kills Grendel, and after a revenge attack by Grendel’s mother, he vanquishes her too in her underwater cave.

Beowulf’s time at Hrothgar’s court lets him observe its politics: an old and impotent king, young men hungering to rule, a queen protecting her sons’ inheritance, and a princess doomed to be a failed peace bride. But fifty years later, in his old age, he no longer remembers how quickly things fall apart. Now king of the Geats, he rashly decides to enter into single combat with the dragon currently scorching his populace and to win the treasure it guards. The encounter proves fatal, and while he dies like a hero, the Geatish people know the score. Beowulf has left no heir to protect them, and their enemies the Swedes are raring for revenge.

As the flames consume Beowulf’s corpse, a nameless woman sings a dirge about the humiliations and captivity to come. Beowulf’s thanes then ride around his burial mound, lamenting their lost leader. They praise him for being the gentlest, kindest, most gracious of kings. It is an unexpected encomium when we think of Beowulf’s brawny reputation, but understandable from the perspective of his subjects. A ruler is judged not only by the wars he wins but by the peace he brings. Yet the final detail in this eulogy—the last word in the poem is lofgeornost, meaning “most eager for praise”—is ambiguous: Beowulf’s desire for glory is what led to his people’s destruction.

Headley’s translation of these closing lines heightens their violence. The mourning woman keens with horror at the “reaping, raping, feasts of blood, iron fortunes/marching across her country, claiming her body.” Nor is Headley’s Beowulf the mild, elder king of the Old English; his thanes mourn him with a song better fit for a lost fraternity brother:

He was our man, but every man dies.

Here he is now! Here our best boy lies!

He rode hard! He stayed thirsty! He was the man!

He was the man.

Headley flattens Beowulf into the mold of twenty-first-century American masculinity in one of its crudest forms. He swaggers into the poem sporting his burnished helmet like a backward baseball hat, and leaves it in a blazing trail of clichés.

For a poem that exists in a single modest manuscript, one that barely escaped a library fire in 1731, Beowulf has done well for itself. The scholar Marijane Osborn counted over three hundred translations and adaptations made between 1805 to 2003, including a Spanish book for children, an Italian comic strip, and about ten versions in Japanese, as well as movies, screenplays, and musical scores. (My favorite of these is the 1974 rock opera by Victor Davies and Betty Jane Wylie, mainly for its song “Armless, Charmless, Harmless Grendel.”)

Advertisement

Headley’s Beowulf is not the first by a woman; at least two dozen others have tried their hand at telling this story of ancient men in modern English. The translator’s gender has not always meant much for the end result. The earliest versions by women, generally for use in schools, gave female characters less power than they had in Old English, or erased them altogether. Most translations simply read like others of their time. Meghan Purvis’s 2013 Beowulf took a new direction, however, giving a long speech to the tragic peace bride Hildeburh (who is silent in the original) and expanding the stories of other women in the poem.

Headley’s career has spanned an unusually wide range of genres, with early science fiction and fantasy stories, a memoir about accepting all invitations to go on dates, an alternative history of Cleopatra, and a young-adult novel set in a mythical cloud realm once described by a Carolingian bishop. She has spoken about her enduring fascination with Grendel’s mother, sparked by reading the Beowulf story in a children’s version around age ten. Her obsession resulted in a 2018 novel, The Mere Wife, loosely based on the Old English epic, and then the project to translate the poem itself.

The protagonist of The Mere Wife is Dana Mills, a war veteran who survives kidnapping and possibly rape in an unspecified Middle Eastern country. She takes refuge in a cave near Herot Hall, a white American suburb filled with terrified Stepford wives and their cheating husbands. Beowulf is transformed into Ben Woolf, a cop who tries to distract from his mediocrity with senseless violence against Dana’s mixed-race child, Gren. This dreamy, lyrical novel hinges on an insight long available to readers of Beowulf: its monsters are more human than they seem at first sight, and its people more monstrous. Dana and Gren appear inhuman to wealthy suburbanites because of their trauma, skin color, and poverty. But a status-obsessed housewife turns out to be the real dragon.

Headley pursues a similar line of thought in her Beowulf translation, elevating Grendel’s nameless mother from the aberrant creature of disgust that many other translations make her out to be. In her introduction Headley writes, “My own experiences as a woman tell me it’s very possible to be mistaken for monstrous when one is only doing as men do: providing for and defending oneself.” She turns the much-maligned revenger into a “warrior woman” and “reclusive night-queen” who rules over an otherworldly kingdom. This is in line with the Old English text, which presents the mother as more heroic and human than modern readers tend to expect. Headley makes her a notch fiercer and slows down her quick and brutal death to allow her a cinematic final bow: “The house of her head/raided…. She bent as though praying,/and was spent, sinking to the stones.”

Surprisingly, Headley is restrained with the poem’s other women, mostly queens and princesses struggling to save themselves and their children as their clans wage war. Subtle choices of diction tease out their powerlessness in a culture shaped by men’s feuds, but beyond this they resemble their Old English counterparts closely. Headley allows herself greater liberty with Beowulf’s beasts and inanimate objects, turning them into an unexpected female supporting cast. In the royal funeral of Scyld Scefing that opens the poem, the dead king is placed in the bearm of a ship. It is a word that can mean “bosom” or “lap,” and is mostly used in Old English to express the protection and comfort men offer: a father’s lap, Jesus’s chest. We tend to think of ships as feminine now, but the Old English words used for “ship” here are either masculine or neuter. Headley turns Scyld’s burial ship into “an ice maiden built to bear/the weight of a prince,” hinting at a destined, perhaps painful, wedding night. In transforming Beowulf into an allegory of twenty-first-century American toxic masculinity, Headley suppresses some of the complexity of early medieval manhood.

The result is a story of men’s violence that runs like groundwater through the poem. After Beowulf kills Grendel’s mother, the Old English poem describes his sword melting “just like ice/when the Father loosens the frost’s fetters” (in Roy Liuzza’s close to literal translation). In Headley’s version, God “releases/hostage heat, uses sway over seasons to uncage/His prisoner, Spring, and let her stumble into the sun.” The thaw of winter becomes a moment of shocking violence in the natural world. In a flashback much later in the poem, when the last survivor of a civilization ruined by strife buries its useless riches, he imagines the earth as a woman:

Advertisement

Hold these, Mother Earth. Men have lost

their grip. We mined this metal from you,

forged it for fighting, ruined ourselves warring

Against one another.

Where the Old English sketches the sparse outlines of the story—people take gold from the ground, they die in war, and the treasure returns to the soil—Headley paints a picture of reckless, callow men caught in a cycle of ecological self-destruction.

By making so much of what is nonhuman feminine, Headley implies that men’s only way of loving the world is by fighting or plundering it. A dragon finds the last survivor’s hoard and watches over it jealously, only to react violently when a thief steals one cup from its lair. Headley cannot resist making the dragon female too, and although the thief is pitiful, he “invade[s] her bedchamber” and glimpses her “secret dreaming-place.” It is a strangely intimate encounter with a dragon, who reacts accordingly: “Up she rose, raging, grieving, though to cry out/was to confess she’d been stripped while sleeping.” Nor does death save her from further violation. When the Geats heave her corpse into the sea, they are “brine-bedding that beast-bride.” Finally, when Beowulf’s men try to gather the loot from the dead dragon’s cave, they discover that “the curse on that stony womb had been set by men/who’d impregnated it with treasure.”

It must be frustrating that there is so little sex in Beowulf. At times, Headley seems desperate to put it in. This leads to awkward moments. When Beowulf arrives home in Geatland, his (also female) ship “sang out for the final/push, thrusting herself at the shore,” then is moored to prevent “the waves from seducing her again.” Why is the boat having an orgasm, one wonders, and is it the shore or the water that does it for her? Readers may find it refreshing to hear Beowulf acknowledge that Hrothgar’s royal marriage diplomacy amounts to “sending his precious daughter to fuck his foe’s son.” But the line appears in Beowulf’s formal report to his lord about the situation in Denmark, and is nestled among stately phrases that, in Headley’s translation, recall the courtly rhetoric of the Old English. Is Beowulf a politician or a locker-room blowhard? There was a difference, once.

Headley hits her mark, however, when she turns her attention to what is missing from her characters’ sex lives: reproduction. Early in the epic, when Beowulf arrives at Heorot, his boasts are challenged by Hrothgar’s adviser Unferth. Headley allows Beowulf a biting comeback: “Your sword’s soft, son.” It’s a clever addition, foreshadowing a scene in which Unferth’s sword really will fail, and hinting at the larger irony of the poem. Beowulf is in fact the man always left holding a useless sword, in more ways than one. When he dies in combat with the dragon after years of ruling well, his people are doomed because he left no son to inherit the throne.

The world depicted in this Beowulf is sterile because it forgets women. While Beowulf busily makes a name for himself fighting, nobody remembers the woman who birthed him: “His mother, I forget who she is—is she still alive?” Women bring men forth and work to keep them alive, but their labors are wiped away in war: “These men who’d been tended/by those who loved them were carcasses now.” To bring the point home, Headley lightly recasts a scene in which the Geatish warriors spear a serpent in Grendel’s mere, showing how barren this thoughtless killing is: “They cornered it, clubbed it, tugged it onto the rocks,/stillbirthed it from its mere-mother…made of it a miscarriage.” Women make the world, and men make their legends by destroying it.

To pull those legends into the twenty-first century, Headley treats American vernaculars like an all-you-can-eat buffet. At times, her Beowulf croons like a country song, as when the men in Hrothgar’s hall sing of their boyhoods, “silvered heart aching/for the good old golden days.” Elsewhere, manhood comes across as curt and colloquial: while preparing to fight Grendel’s mother, “Beowulf gave zero shits.” For a moment, Beowulf even sounds like Barack Obama, the medieval hero’s “lemme be clear” borrowing the rhythm of a modern stump speech while maintaining the resonant terseness of Old English heroic verse.

At its best, Headley’s verse channels the energy and formal sophistication of hip-hop. Her young Beowulf approaches the Danes with anapestic braggadocio: “I’m the strongest and the boldest, and the bravest and the best.” It’s an old-school sound, reminiscent of LL Cool J’s “I’m a tower full of power with rain and hail.” The face-off between Beowulf and Unferth plays out like a rap battle, with end-rhymes, slant rhymes, and over-the-top assonance springing the words off the page. Some of Headley’s choices in this register are exquisitely witty, as when Beowulf retorts, “Let me drop some truth/into your tangent.” He sounds like an MC, but his taunt also foreshadows the lengthy historical digressions that will dominate the second part of the epic. These narrative tangents—on Beowulf’s rise to power, the Danes’ doomed alliances, and the Swedish–Geatish wars—complicate the audience’s understanding of truth and communal memory. And one aural technique can convey different tones. In his prime, Beowulf gloats about bringing home “sea-booty, gore-loot,/no big whoop.” Fifty years later, when the dragon sets his hall aflame, such insistent assonance sounds menacing: “He’d been ghost-throned by the skyborn gold-holder.”

Headley fills the poem with deliberate anachronisms, few of which do more than give the poem a modern finish. After Grendel devastates Hrothgar’s hall, we learn that the “news went global.” Beowulf at his best is praised for “never punching down,” which must be why Hrothgar’s man “unexpectedly stanned” for him. A dragon “tagging the sky with flaming sigils” is sublime. But it is unsettling to move from a gorgeous Homeric simile in which Grendel hunts men like “an owl/mist-diving for mice, grist-grinding their tails/in his teeth” to Internet lingo like “sidebar” and “Hashtag: blessed.” This is a translation of its moment, and will age accordingly.

It is meant to. “With this text, perfection is impossible,” writes Headley, a fair warning to anyone expecting the steady and smooth lyricism of Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf. A better point of comparison for Headley’s undertaking is Bernardine Evaristo’s The Emperor’s Babe, a verse novel that combines contemporary dialects and modernized Latin to convey the hubbub of multicultural London in the year 211 AD. Evaristo’s book is just as irreverent as Headley’s, but she manages her linguistic mix with greater control by keeping the characters’ voices consistent and dividing the story into sections, each with its own mood and tempo.

Indeed, Headley does much the same in The Mere Wife, allowing the reader to become engrossed in the story. In her Beowulf translation she changes register with whiplash speed inside individual speeches, even lines. Take the faithful thane Wiglaf’s heartfelt appeal to Beowulf’s men to stand by their king in his last battle, which moves from casual to heroic in a few beats: “Bro! Listen! Remember in the mead-hall,/we swore to our lord we’d stand by him.” The first “bro” in this Beowulf is a kick. By the twentieth, it starts to feel like a gimmick.

Then again, in veering blithely between high and low, Headley strikes a surprisingly medieval note. Medieval artists did not share our standards of subdued decorum, and many a poem of the time shocks modern readers with its inconsistent tone. In one of her playful moments, Headley describes Grendel’s impending attack on Beowulf and his sleeping men, who are “roosting like roasting chickens.” Grendel is a “fox that stalks the night” who does not know his “goose would be cooked, his funeral/banquet bruised and blue.” These heaped-up culinary metaphors interrupt the scene’s rising tension and deflate the heroism of the encounter. It seems like a mistranslation, and yet it is precisely what another early medieval author did to Beowulf. The poet of Andreas, an anonymous Old English poem about the apostle Andrew’s visit to a land of cannibals, combined ironic borrowings from Beowulf with grotesque gastronomic puns in a way that made the older epic’s heroes look ridiculous. He (or she) would have approved of Headley’s wordplay.

And, stylistically, Headley’s Beowulf is sometimes more medieval than the original. Old English poetry takes its shape from its metrical patterns and the alliteration of stressed syllables. Each line has two or three alliterating words, though sometimes the repeated sound runs across several lines, possibly to raise the emotional pitch of a passage. Early English poets liked alliteration so much that they used it when writing Latin too. The seventh-century churchman Aldhelm was particularly good at this—he began one letter with fifteen words that start with the letter “p.” Some translators of Old English keep their alliteration minimal, abandoning it where it might sound too artificial to the modern ear. But Headley leans into the medieval sound, having Beowulf describe his killing of a sea-monster with a sibilant cascade not in the original poem: “I made it a sleeper as it leapt,/severed its spine, spiked its skull, and split it into smithereens.”

Old English poets rarely used rhyme. When they did, it was an additional flourish to give a passage greater intensity. Headley employs rhyme often, effectively fusing medieval ornament and the sound of modern rap and spoken-word poetry. When she has Grendel flee “from hall door/to mere shore” and leave “a river of gore,” she gives a sense of how ornate Old English poetry could sound when the poet was showing off. Another rhetorical figure beloved among medieval poets was polyptoton, etymologically connected words in close company. Grendel’s “joints unjoined,” and the death of the dragon, “melted, smelting/dark intention into the metal,” reveal how pleasing the effect can be. Kennings, compressed metaphors such as “battle-sweat” for blood or “whale-road” for sea, also find new counterparts here. When Beowulf tries to speak after the dragon fight, “the knife-tip of a sentence stabbed from his locked/lung-vault.” Burdened with neo-medieval metaphor, the phrase is hard to grasp and harder to say—as halting as a parched hero’s dying words.

The Old English Beowulf explores the tragic failure of peace-making among rival groups, the way old grudges bring down good rulers. The poem is haunted by the inevitability of violence; it is not in love with violence. Headley’s Beowulf rings with an altogether modern jingoism. Hrothgar’s Danish kingdom expands into a vast territory for men to conquer: “There was a lot of country/between the coasts, a lot of open air beneath the sky.” Hrothgar does not fight for strategic reasons, but because “war was the wife [he] wed first,” suggesting the emotional, nearly fetishistic attachment of Americans to their military. After Beowulf dispatches his first two monsters, Hrothgar lectures him on how to be a good “homeland healer,” explaining how to avoid turning into the evil king Heremod, whose “heart/was not a hawk but a drone.” It could be fatherly advice from Bush Sr. to Bush Jr.

As in The Mere Wife, Headley uses the skeleton of a medieval epic to tell a story about how the love of power corrupts even those human communities that seem most comfortable, most civilized. One might think Grendel’s attacks bad enough. Hrothgar’s court is scarier. Its formal celebrations consist of men drinking “the love of country in each draft,” and processions of “white men on white horses,” an eerie visual evocation of the Ku Klux Klan. In order to complete the inversion between the monsters and heroes of the Old English poem, Headley makes Grendel into a working-class hero, “living rough for years” and “bringing pain to the privileged.”

After Beowulf tears Grendel’s arm off, it is hung from the rafters for all the Danes to see. With its steel-like claws it horrifies the nobles, and Headley suggests this is another case of the rich being unable to see the humanity of the laborers who serve them. In an interpolation she describes Grendel’s hand as “callused as a carpenter’s, weathered/by work and warring.” Headley’s downtrodden, proletarian Grendel might have been believable if she had not insisted on his mother being a magnificent queen elsewhere in the poem. As it is, her translation feels as though she is checking ideological boxes to make each monster more sympathetic. The Old English poem is more consistent here; in it, Grendel’s gargantuan hand belongs to a hilderinc, or warrior, as befits the son of a noble, powerful woman.

Headley falters when she tries too hard to make Beowulf modern, whether it’s by turning it into an allegory of class struggle or by figuratively putting its hero in a polo shirt. She is astute, however, in recognizing that the medieval epic tells a story about men’s violence that never really ended. This is a poem about fathers: their burdensome legacies, their failures to protect their children, their unaccountable absences. “Grendel will never have a single son/to brag on his daddy’s battles,” boasts Beowulf—but neither will he. The only thing the men of Beowulf succeed in leaving behind is war. Its poet knew this, knew that kings grow old and foolish, that splendid civilizations go up in flames, and that every victory is hollow and provisional. As Wiglaf puts it in his account of a calamitous battle that saw the Geats briefly still their feud with the Swedes: “Now they were custodians of the bloody mud.”

This Issue

December 3, 2020

Bolivia’s Tarnished Savior

Democracy’s Afterlife