In Britain, as in the rest of Europe and the US, the Black Lives Matter movement and the severe effects of Covid-19 on Black, Asian, and other ethnic communities have sharply awoken many of us to the nation’s historic institutional racism. A report by Public Health England published in June found that nonwhite Britons had up to a 50 percent higher risk of death from the coronavirus than white Britons (for Bangladeshi Britons this rose to twice the risk). Beyond vulnerability to infection at work, explanations for their higher death tolls include living in close-knit urban groups where social distancing is difficult; having to use public transport; the deprivation and poor health of many immigrants; and their reluctance to approach doctors or hospitals, part of a general distrust of authority.

The communities affected include a large proportion of the people who have worked in hospitals and nursing homes throughout the pandemic as doctors, nurses, porters, and cleaners, as well as workers in other essential, low-paid jobs. Yet while the government talks of gratitude and respect, in May the Conservative majority in the House of Commons pushed through an immigration bill that will establish a points system for immigrants like that of Australia, with an earnings threshold aimed specifically at deterring “low-skilled workers.” One concession is the promise of a so-called NHS visa—if we need you in our hospitals, we’ll bend the rules.

At the same time, as Britons have been absorbing the stark Covid-19 disparities and watching the protests after the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the toppling of statues of slave traders and colonialists, the shame of the Windrush scandal has continued. The Windrush Generation, as it is known, includes around half a million people who arrived in the UK between 1948 and 1971, mostly from Caribbean countries (the name comes from the Empire Windrush, the passenger ship that brought some of the first immigrants from the West Indies to the UK). In 1971 they were granted indefinite permission to remain, but thousands were children who had come on their parents’ passports and had no documents of their own. They were thus at a loss in 2012, after changes to immigration law, when they were asked to produce evidence of their status in order to continue working, access public services, and even remain in the country.

This bureaucratic harassment intensified when Theresa May, then home secretary, declared a “hostile environment” strategy on immigration, leading to thousands being deprived of their rights, losing their jobs, and sometimes being deported to countries they’d left decades ago or had never known at all. A devastating independent report released in March this year concluded that the Home Office had shown “ignorance and thoughtlessness” on the issue of race and demanded that it make an unqualified apology. In June the UK’s Equality and Human Rights Commission announced that it was launching an inquiry into the legality of May’s policy.1

To understand this toxic situation and to ensure that horrors like the disproportionate Covid-19 deaths and the Windrush deportations can’t happen in the future requires a ruthless look at the past as well as the present. This means acknowledging and teaching the darker side of Britain’s imperial legacy, but also reading that history from the viewpoint of the postcolonial immigrant communities themselves, which have been woven into British life for centuries. This is the story that Panikos Panayi tells in Migrant City: A New History of London. The book demonstrates a continuing paradox: on the one hand, the great contribution of migrants to the life of the capital, and on the other, their persistent exploitation in vital, low-paid occupations and their battles against embedded racism.

Panayi sees London as a special case among world cities, both in its long history of immigration and in its rapid rise as a mercantile, industrial, and political hub, “the heart of Empire.” Although he considers early waves of immigrants—like the Jewish settlers fleeing pogroms at the time of the First Crusade, the German merchants and Italian financiers and craftsmen of Tudor times, and the refugees from religious wars in the seventeenth century—he concentrates largely on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This is a hugely ambitious enterprise, made manageable by a focus on specific groups—notably the Jewish, Irish, German, Bangladeshi, and Greek Cypriot communities, with a more cursory examination of the West Indian and Chinese experiences.

Panayi is a professor of European history at De Montfort University, in Leicester, and the author of several works on multiculturalism, ethnicity, and racism in Britain. But his own childhood, rather than his academic work, provides the starting point for this story. In the prologue he tells us what it was like growing up with his Greek Cypriot parents in north London, where his father was a pastry cook, in the late 1960s and early 1970s: going to school, speaking no English; being punched by a bully who was eventually subdued by Panayi’s father; making friends with other young immigrants—West Indian, Sri Lankan, Turkish, and Spanish—as well as with white English kids; being taught by two Indian women who wore saris. The early experience of diversity, he notes, “formed the way I think and orientate myself.”

Advertisement

With some exceptions, most of London’s migrants have been driven here by fear. Desperate for a place of safety, they have fled state, religious, or majoritarian persecution, as well as war zones and famine-ravaged countries. London has been both a destination and a starting point for movement across Britain or abroad, particularly to the United States. Offering a promise of freedom, the city has also sheltered revolutionaries in exile and anticolonial campaigners against the empire itself—from “Karl Marx, Lajos Kossuth and Giuseppe Garibaldi through to Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Jomo Kenyatta, Mahatma Gandhi,” Panayi notes—and it has been a base for governments in exile, like the Free French under Charles de Gaulle during World War II.

All that influx has made the city a decidedly polyglot place. Today’s Londoners come from almost every country in the world, and over three hundred languages are spoken there. The most recent census, taken in 2011, showed that one in three Londoners was born outside the United Kingdom, and less than half the city’s inhabitants described themselves as white British.

By the time of that census, people from immigrant backgrounds lived in almost every district of the city, but this was not always the case. In the past, newcomers settled in particular neighborhoods, like the Irish “rookery”—a term that came from associating the crowded slums with noisy colonies of rooks nesting in a copse, and also from the rooks’ alleged habit of stealing—in St. Giles in central London in the eighteenth century. Like many poor immigrant districts, this was damned, according to the historian Dorothy George, as “a centre for beggars and thieves and the headquarters of street sellers and costermongers.”

Other clusters have included the Italian population of Clerkenwell, on the northern fringes of the City of London; the Jewish East End in the late nineteenth century; the so-called colored quarter in South London, especially Brixton, which Panayi calls “the most visible ghetto in post-war London” after World War II; and the Sikh community in Southall, West London. The East End, close to the city’s original docks, has been the first area of settlement for many newcomers. Huguenot refugees of the late seventeenth century were followed by Irish, Germans, and Chinese, and then by Ashkenazi Jews from Central and Northern Europe.

At every stage, even sympathetic observers have seized on these groups as “exotic” and “peculiar.” William Evans-Gordon, describing the Jewish community in 1903, concluded that “clannishness, tradition, a sort of historical fear of separation from their co-religionists, their obligation to observe peculiar ritual ordinances, added to the promptings and difficulties which tend to keep men of the same tongue and habits together in a strange land,” brought the Jews “into the already crammed and congested” East End.

This quarter remained the poorest in London. Housing was cheap and, in the 1880s and later, new arrivals could find work in the immigrant-run garment industry, which was first established in the area by Huguenot weavers. As Jewish families prospered and moved to the suburbs, their places were filled by new arrivals, particularly the Bangladeshi settlers of the late twentieth century, who took their places in the sweatshops of the rag trade. Immigrants did the sort of manual or temporary jobs that the poorest white British disdained. Often this meant a decline in status from their occupations in their country of origin, and the low pay forced them to take more than one job to survive.

The main resort for women was sewing or washing, or going into domestic service—though if the only way to survive was to start your own business, this often meant prostitution. And as late as the 1970s, refugees from totalitarian regimes in Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia—among them many doctors, lawyers, professors, and artists—became “cleaners, kitchen assistants, porters, waiters and waitresses, hotel chambermaids and security guards.” Though not mentioned by Panayi, the trend has continued to this day, with unpaid au pairs and poorly paid cleaners from Poland, Romania, and Ukraine.

For the Irish, the main trade was always building, beginning with the navvies who arrived during the Irish famine of 1845–1849 and laid London’s new sewers and railways. A century later, the Civil Engineering Foundation was still recruiting men at job centers in Ireland, and Irish construction workers were heavily involved in major projects of the 1960s and 1970s, like the South Bank Centre and the Barbican. Aggressive public-sector recruitment also brought nurses from the West Indies and Ireland starting in 1948, when the founding of the NHS created an urgent demand. In 1950 the London Transport Board opened a recruitment office in Dublin, and six years later began hiring in the West Indies, first in Barbados and then in Trinidad and Jamaica. British Rail followed suit.

Advertisement

The welcome for Britain’s black “colonials” was not always warm: about half of the West Indians who arrived on the Empire Windrush spent time in the Clapham Deep Shelter, a web of tunnels below an Underground station in South London that had been built as a wartime bomb shelter and filled with rows of bunk beds. The experience, as one arrival put it, led to much “frustration, loneliness, sadness, regret.” As Panayi points out, many of those who arrived from the Caribbean then and throughout the 1950s would spend their entire lives working on London’s buses, for the Underground, and in the city’s hospitals.

In all periods, however hard people looked for work, often they found none. In 1961 the rate of unemployment among West Indian men was almost double that for men born in England. And in all periods, poverty and homelessness abounded. This is still true today: in 2013 the majority of London’s homeless, whom one constantly sees curled up in doorways and on steps, were not UK nationals, and over 500,000 undocumented migrants are now estimated to be living in London, half of them failed asylum-seekers.

The history is cruel. Many black slaves, brought to Britain by plantation owners and freed after the abolition of the slave trade in the empire in 1807 (although colonial slavery itself was not abolished until 1833), became paupers, sweeping street crossings, knitting nightcaps and socks, or begging. Henry Mayhew’s 1861 survey London Labour and the London Poor includes countless references to “foreign beggars,” “destitute Poles,” “hindoo beggars,” and “negro beggars.” Mayhew estimated that there were, in addition, some 10,000 Irish hawkers, selling fruit, nuts, and oranges—“indeed the orange-season is called the ‘Irishman’s harvest.’” They followed the generations of Jewish street-sellers, the “old-clothes men, who may have counted in the thousands by the end of the eighteenth century,” and who collected the cast-offs of wealthier Londoners and sold them at the Rag Fair near Tower Hill and, in Mayhew’s time, in Petticoat Lane.

The more regular, specialized businesses run by immigrants ranged over time from Huguenot weavers to Italian ice cream makers; German bakers, butchers, and confectioners; Jewish grocers, carpenters, and tailors; Cypriot clothing workshops; Chinese laundries; and, of course, modern Chinese and “Indian” takeout restaurants (many are now Pakistani- or Bangladeshi-owned and run).

It’s hard to imagine life in London—or anywhere in the country—without the Asian corner shop, open early and late and on weekends. Many of these originally opened after thousands of Asians left Kenya in the late 1960s, descendants of settlers and indentured laborers brought from the Indian subcontinent to the British East Africa Protectorate in the 1890s. After Kenyan independence in 1963, many declined to exchange their British passports for Kenyan citizenship and, in 1967, under new immigration laws, were unable to get work permits in Kenya. A similar exodus occurred when Idi Amin expelled all Uganda’s Asians in 1972. Although many of the second and third generations have moved into business or a profession like law or medicine, families with origins in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka still run most of the corner shops.

Panayi shows how some small enterprises became giants, like the Jewish-owned Tesco, which started as a group of market stalls in Hackney, and Lyons, which grew from a tea-shop chain into a catering empire. And he recognizes that not all immigrants are poor. At the other end of the scale from the small shopkeepers are the elite members of the international rich—bankers and stockbrokers, Greek ship owners, Indian billionaires like the steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal, or Russian oligarchs such as Roman Abramovich.

In all commercial initiatives, large and small, social networks proved important. The initial network was usually based simply on the immigrant’s place of origin—astonishingly, London’s first large Italian community mostly came from only four areas in Italy: the Como, Parma, Lucca, and Liri valleys. The family or ethnic group then provided labor for shops or workshops, as well as sources of loans and investment, Panayi explains, “partly because of the fear of rejection based on racism if approaching banks.”

One crucial bond that cemented the closeness of an immigrant group was provided by food—the taste of home. In a fascinating chapter toward the end of the book, he discusses the growth of the London restaurant trade, concluding that migrants “may have had a more profound impact upon eating out than any other aspect of the history of the city.” As well as charting the evolution of chic French and Italian restaurants and the Greek Cypriot coffee and sandwich bars of Soho, Panayi describes the sellers who began by catering to their own ethnic minorities, from the Jewish fish-and-chip shops to the vast range of cafés and pop-up eating places of today.

The most obvious network, however, is that of religion, visible in “the building of churches, synagogues, mosques, mandirs and gurdwaras.” These are also markers of the second-generation migration from the inner-city slums to the outer suburbs. One East End building, on the corner of Brick Lane and Fournier Street in Spitalfields, is emblematic of this. It began as the Huguenot Neuve Église in 1743, then mutated into the Machzike Hadath, the Spitalfields Great Synagogue, and in the late twentieth century became the Bangladeshi Jamme Masjid, finally crowned with its minaret in 2009. The Roman Catholic St. Peter’s church in Clerkenwell was built for Italian immigrants in 1863, while a rash of churches and schools followed the arrival of thousands of Irish Catholics in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as Greek and Russian Orthodox churches, culminating in St. Sophia in Bayswater, which became a cathedral in 1922.

But in Victorian times, as Panayi explains, London also teemed with native English Protestant “missionaries” bent on converting Italian and Irish Catholics, as well as people of other faiths. And while some evangelists like Joseph Salter, who labored from the late 1850s to the early 1890s among the “Asiatics” of the docks, created a safety net for the destitute with handouts and hostels, missionary activities could also, Panayi points out, be described as “a type of internal imperialism, searching out souls for conversion in exactly the same way as their brethren in the British Empire.” The patronizing attitude that persisted within the established Anglican Church drove immigrants away even into the twentieth century, encouraging West Indians and Africans, for example, to establish their own Pentecostal churches.

Migrant City is dense with sources and statistics, and Panayi is good at sorting out patterns, such as the way that varied faiths have so often begun by setting up temporary places of worship in a house, above a shop, or in a shed. This practice among early Sephardic and Ashkenazi communities was renewed in the late nineteenth century, when the new wave of Ashkenazi settlers, alienated by the “imposing grandeur” of the established synagogues, set up their own meeting places, independent hebroth or chevroth in back rooms and attics.

A similar process took place with the “house mosques” of Islamic migrants and the home temples of Hindu settlers and Sikhs, each community moving slowly toward grand statements, culminating in the London central mosque in Regent’s Park; the great Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in Neasden, northwest London; and the Singh Sabha Gurdwara in Southall, the largest Hindu and Sikh temples outside India. Such buildings are assertions of permanence but not necessarily, it turns out, of regular adherence: church and synagogue attendance declines as communities become more secular, intermarry, and turn away from traditional practice. The division between the devout and the lapsed becomes as pronounced as that between the faiths themselves.

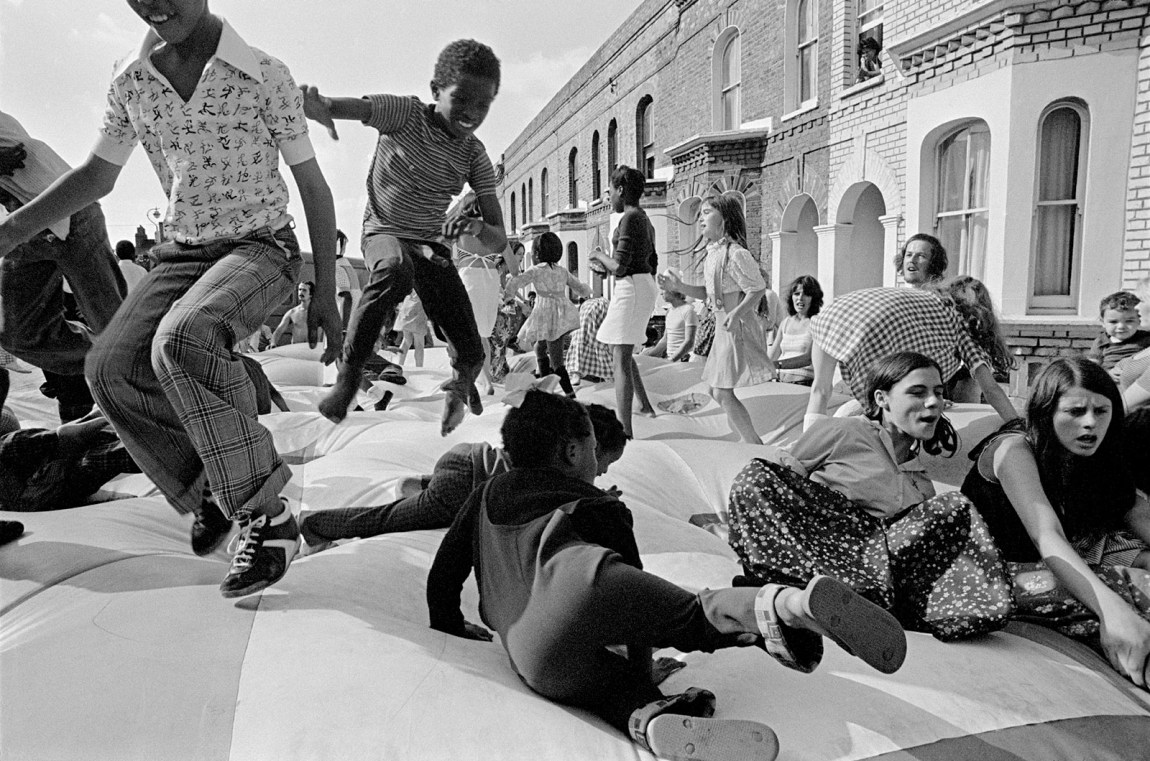

London’s immigrants have striven successfully, often against fierce racist opposition, to become representatives—on councils, in labor unions, in Parliament—a battle embodied today in committed figures like David Lammy, member of Parliament for the North London constituency of Tottenham, and the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan. Underlying this positive account, however, is a saga of hostility. Those on the lower end of the employment ladder already experience discrimination, while “migrants become fair game during times of heightened ethnic tension.” Panayi rightly places at the center of his book a story of prejudice that runs from the riots against the Jews in 1189 as “Christ killers and moneylenders” to the present time. Although first- and second-generation migrants have made friends and found lovers and partners among other ethnic groups, including white Britons, “racism always remains in the background,” he writes. Nativist aggression in parts of the city where people from elsewhere tried to find new homes—in the East End or in Notting Hill in the 1950s, for instance—has, he notes, always gone hand in hand with “highbrow racism,” leading to legislation like the Aliens Act of 1905, which introduced immigration controls for the first time, denying entry to “undesirable immigrants” as defined by the Home Office, and the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962 that ended the automatic right of citizens of the British Commonwealth and colonies to settle in Britain.

As an extreme example of state-supported xenophobia, Panayi invokes the subject of one of his earlier books, London’s large German community, all but invisible in British history books, that was essentially wiped out in 1915 during three days of xenophobic riots.2 In the aftermath, Germans faced internment and deportation, while “the government confiscated any German property which had not faced destruction, whether it belonged to the local baker and butcher or the Deutsche or Dresdner bank.” In this grim chapter, he also tracks the violence toward the Irish Catholics, as well as the “Jew-baiting” of the eighteenth century, a prejudice that never vanished and that surfaced stridently in the 1930s with Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists.

The less visible “everyday antisemitism” of the early twentieth century still crawls not far below the surface. So does the wider prejudice against long-resident ethnic groups and recent asylum-seekers, often exacerbated by the institutional racism of the Metropolitan Police. (The excessive use of “stop and search” and serial deaths in police custody have both been highlighted in the Black Lives Matter demonstrations this year.) “Hundreds of people,” Panayi concludes, “have perished as a result of the actions of thugs over the centuries.” It is horrifying to be confronted with the full litany of the murders of West Indians, the “Paki-bashing” of the 1960s and 1970s, or the experience of black footballers running onto the pitch to be greeted with chants of “you black bastard,” showers of spit, and an onslaught of bananas.

Migrant City is based on years of scrupulous research: the notes and bibliography amount to more than a quarter of the text. But while it rings with passion and commitment and provides invaluable background, it can be frustrating for a general reader. There is a lack of clarity, for example, on legislation, Home Office initiatives, and their impact. And despite the wide use of surveys and interviews, and the quotations that open each chapter, we have little sense of migrants’ own imaginative response to London. There are brief chapters on musicians, boxers, and soccer players, but no consideration of the wealth of novels, films, and poetry of the last hundred years, from Israel Zangwill’s Children of the Ghetto (1892) and Samuel Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners (1956) to the explosion of recent fiction and writing like Jay Bernard’s poetry in Surge (2019), which chronicles black British history against the background of the Windrush scandal and the 2017 Grenfell fire, the deadly blaze in a West London apartment tower in which most of the seventy-two victims were from ethnic minorities.

Above all, one longs for each section to be brought up to date, giving more space to the last twenty years—to encompass the stories of workers from the ten countries added to the European Union in 2004, and of current asylum-seekers from the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, and Afghanistan. Every day I learn new stories. A woman lawyer from Sudan fighting to feed her family; a tradesman and former asylum-seeker from Damascus with four children who makes masks and scrubs for the National Health Service in the pandemic; a young man from Eritrea sleeping in a shopping center. Some succeed, some go under, and the struggle can seem unending. In the words of one participant in the short film Migrant Voices in London, made by the Migrant Research Group at Kings College London, “We’re not there yet. Like, we’ve never arrived, never quite there. Like, we have not completed the journey yet. The goalpost is always further.”

In 2020 thousands of men, women, and children have crossed the English Channel in fragile inflatable boats. They have traveled thousands of miles to get here, and now face detention and hardship. But at some point their journey may take them to the capital. Migration is a living, flowing history—London will be their Migrant City too.