There were three people at the funeral of Mary Ellen Meredith when she died at the age of forty, in 1861: two women servants and an acquaintance of her second husband, the poet and novelist George Meredith. No one else came. Not her father, the comic writer Thomas Love Peacock, then in his seventies, nor any of his family. Not one member of the family of her first husband, the late Edward Nicolls, nor their daughter, Edith, then in her teens. Not, obviously, the novelist, whom she had left in 1857 after eight years of marriage, nor their young son, Arthur. Not the man for whom she’d left him, the painter Henry Wallis, nor little Felix, who had Meredith’s surname (they had not divorced) but was in fact her illegitimate son by Wallis. Not one of the writers or publishers or public figures or friends whom she’d known during her sociable years as the daughter of a well-known literary figure and administrator in the East India Company, and as the wife of an ambitious and rising young writer. None of them came. The vicar did not mark the location of the grave in the Weybridge church where she was buried, and “in a few years no one [would] be able to find her grave.”

In the first Dictionary of National Biography entry on George Meredith, published in 1912, three years after his death, when his reputation as a major Victorian novelist and literary sage was still high, Mary Ellen is referred to as the “flighty” and attractive widow, several years older than him, who, after their life together of poverty, dependence on relatives, literary struggles, and marital discord, “went off to Capri” with the artist Henry Wallis—who had done a famously romantic painting of the death of the poet Thomas Chatterton with Meredith as his glamorous red-headed model. Other early memoirists and biographers of Meredith presented Mary Ellen as a dashing horse-rider, a clever, seductive, and restless character, who abandoned her young son as well as her husband and whose lover then abandoned her to her wretched and lonely last years. The revised Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry of 2004 describes their marriage as becoming “frayed to breaking-point.” After the “trauma of sexual betrayal,” Meredith “creatively transformed” the experience into fiction and poetry.

To see how he did this, you have only to look at his dark, troubled poem-sequence of a marriage in meltdown, Modern Love (1862), or at the satirical accounts of vain men humiliated by being left by a wife or fiancée in The Ordeal of Richard Feverel (1859) and The Egoist (1879). But, to complicate the story, there are also frequent and mostly sympathetic portrayals in his novels of strong-willed, independent, sexually experienced, attractive, and intelligent women with endangered reputations who are misunderstood or ostracized by English society. In any case, whether Mary Ellen is seen as the flighty adulteress who deservedly dies a sad early death or as the unfortunate source of Meredith’s creative invention, the woman herself, in all her complexity, seems to disappear.

Diane Johnson chanced on, and became fascinated by, this obscure life in the late 1960s. Her interest coincided with the start of the women’s liberation movement, when women who had been “hidden from history” were beginning to be reclaimed by feminist historians and critics. Lesser Lives, as her book was called when it first came out in 1972 (the ironic title has now become its subtitle) was an early example of what became a familiar genre, coming out of second-wave feminism alongside publishing ventures like Virago and the Women’s Press. It deserves its status in the NYRB Classics series for its pioneering influence. From the 1970s onward, there were many examples of such restitutionary life-writing, including Phyllis Rose’s feminist account of five Victorian marriages, Nancy Milford’s life of Zelda Fitzgerald, Brenda Maddox’s biography of Nora Barnacle, and, outstandingly, Jean Strouse’s life of Alice James and Claire Tomalin’s of Dickens’s secret lover, Ellen Ternan. In many of these biographies (a lurid example would be Carole Seymour-Jones’s 2001 life of Vivienne Eliot, Painted Shadow), the famous male writer, from out of whose shadow the woman’s “lesser life” is being released, gets a hostile treatment. That’s probably necessary to the revisionist process—certainly part of Johnson’s intention was to deflate George Meredith’s standing. It gives her book, reissued nearly fifty years on, a period flavor—but that’s interesting in itself.

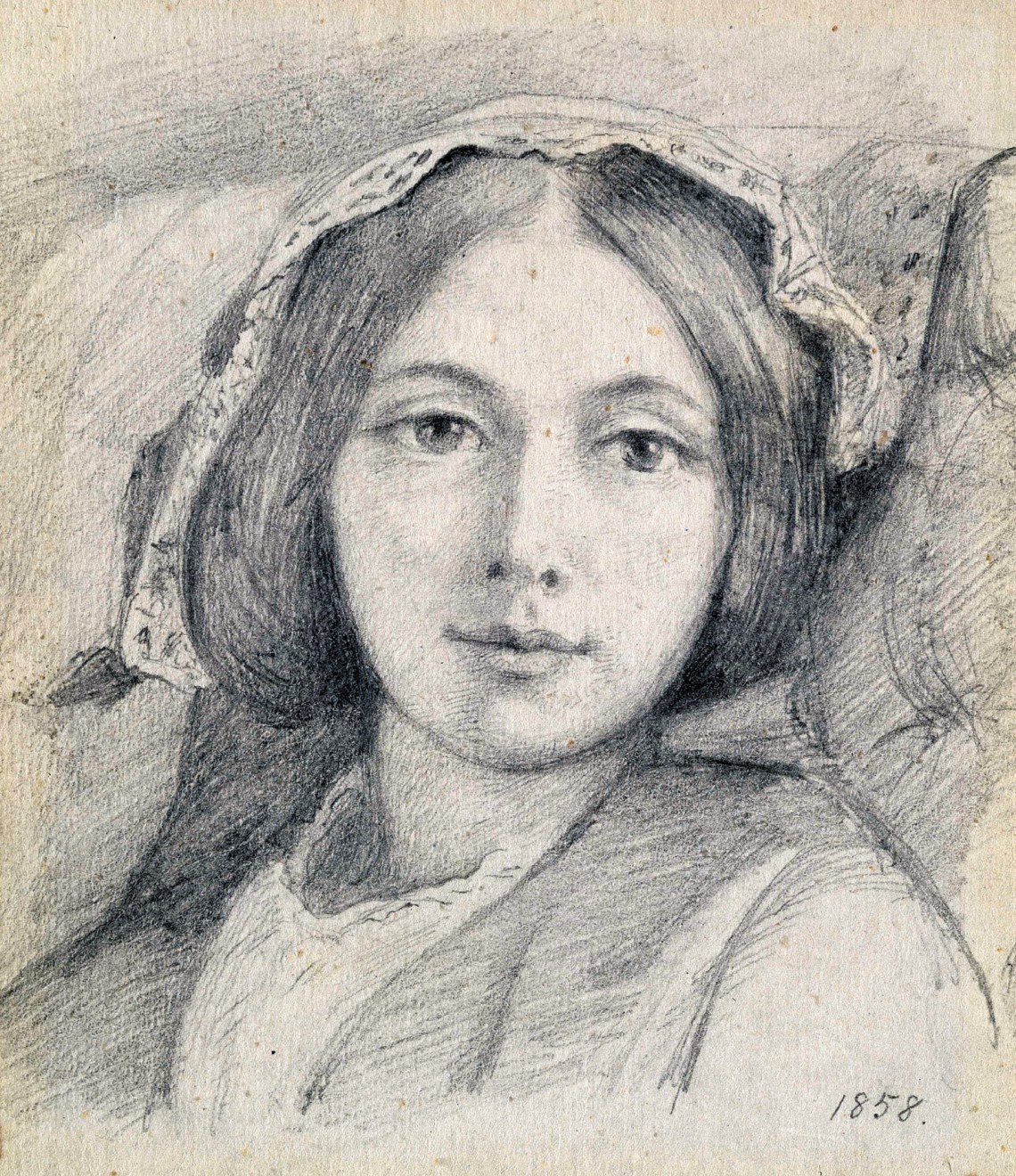

When she started her quest, she had one of those strokes of luck that all biographers dream of. She visited a house in Surrey whose owners had an aunt who had once worked for Felix. They had just moved and had piled all their inherited stuff in a storage room. There, Johnson pulled out from under a bed a box that turned out to contain, on tiny sheets of paper, Mary Ellen’s letters to Henry. From there she began to piece together Mary Ellen’s story. Along the way she found a few other traces: her commonplace book, her earrings, a sketch of her by Wallis, her pink parasol. Coming upon these objects, by luck, she had “an excited sense of certitude” that she would be able to track her subject down.

Advertisement

George Meredith’s first successful novel was The Ordeal of Richard Feverel. Johnson might well have called her story The Ordeal of Mrs. Meredith. She shows us the young Mary Ellen Peacock as the bright, unusually well-educated, favored daughter of Thomas Love Peacock—whose own mother had run away from her husband and brought him up alone. Peacock, talented, attractive, amatory, and a good friend to the bohemian Shelley circle, married, rather surprisingly, a Welsh parson’s daughter, Jane Gryffydh, who was ill at ease in London and developed life-long mental illness after the death of one of her children.

Johnson’s book isn’t only about Mrs. Meredith. Its “lesser lives” also include sad, “mad” Jane Peacock; another is a servant girl named Matilda Bucket with whom George Meredith’s father had an affair (“how one longs to know more about Matilda Bucket”); yet another is a younger sister of Mary Ellen who died at thirty after the deaths of her two children—“but nobody, nobody at all, has kept any track of Rosa Jane.” Johnson hankers after these buried stories—what Virginia Woolf, clearly a strong influence here, called “obscure lives” in A Room of One’s Own. “All these infinitely obscure lives remain to be recorded,” she famously said in that essay in 1929. Diane Johnson sets herself to the task with energy and curiosity.

After Jane Peacock’s breakdown, Mary Ellen, the oldest Peacock daughter, “spirited” and “beautiful,” interested in books and food and a great reader of French novels, became her father’s helper and hostess, and at twenty-two married a young naval officer, son of a famous general known as “Fighting Nicolls.” Johnson fell in love with this dauntless character, who, she said later, in her memoir, Flyover Lives (2014), became a model for her “when times are dark” for his “stamina” and “resolute optimism.” She gives him a surprising amount of space.

Young Nicolls drowned two months after the marriage in an accident in 1844, so Mary Ellen was already widowed when she had their daughter, Edith. Edith Nicolls is another of Johnson’s “lesser lives,” whom “history…has looked right past” but who grew up to be Thomas Love Peacock’s memoirist, head of a cooking school, and writer of cookbooks—an interest she’d inherited from her gourmet grandfather and mother. Johnson provides some of Peacock and Mary Ellen’s lavish recipes, and observes that it wasn’t a good idea for a gourmet to marry a dyspeptic—Meredith always had very bad digestion.

When Meredith fell in love with Mary Ellen, he was twenty and she was twenty-seven. His novels, later on, often featured older women inveigling younger men. The couple were part of a talented literary group centered around Peacock, editing a little magazine, The Monthly Observer, and writing essays and poetry (one or two of Meredith’s early poems may have been hers). In the early 1850s they had no money; Mary Ellen bore “more than one child” between 1850 and 1852 who were either stillborn or died soon after birth. They were dependent on Peacock, who disliked his son-in-law for “his smoking, his finicky diet [and] his literary talk.”

Meredith was struggling for literary recognition. He and Mary Ellen increasingly spent time apart. Like strong meat, she didn’t agree with him: “They had too many debts and miscarriages; their rooms were too dreary and narrow to remain cheerful in. You cannot live on love.” The situation would be painfully dramatized in Modern Love. Wallis, to whom Mary Ellen wrote some wistful, confiding letters before they became lovers in 1856 or 1857, has been presented as an “unscrupulous and cynical” seducer, but Johnson reconstructs him as a “decent fellow,” never a great success as a painter (he ended up as an expert on ceramics) but always devoted to their son.

Johnson deduces Mary Ellen’s state of mind during her marriage and its breakdown from her commonplace book of 1856. This is full of French quotations about love, marriage, adultery, and women’s lives from, among others, Dumas père, George Sand, and the popular Parisian novelist Paul de Kock. Mary Ellen read Dumas fils’s La Dame aux Camélias, Voltaire, Molière, and—like the warring husband and wife in Modern Love—Benjamin Constant’s Adolphe, still in the 1850s a shocking French novel about a young man’s affair with an older married woman, felt by British readers to be “emblematic of worldly cynicism.”

Advertisement

Johnson notes the anti-French sentiments in mid-nineteenth-century Britain: what a relief, say the English matrons, that “the English were not French”! But she doesn’t make as much of this cultural clash as she might have done in her later Paris years—when, in her novel Le Divorce, Constant’s Adolphe is used as an emotional reference point. Nor does she allow for Meredith’s own love of French history, literature, and landscape. He often shows his parochial English chauvinists disparaging all things French, like the “Egoist” Sir Willoughby Patterne who describes French “sham” and “pretension” as “irreconcilable with English sound sense.” The worst term that can be applied to one of his dangerously independent-minded women—Diana Merion in Diana of the Crossways or Margaret Lovell in Rhoda Fleming or Clara Middleton in The Egoist—is a French one: “arrant coquette.” One of Clara Middleton’s admirers calls her “French” in her “disposition” “to challenge authority” and her desire for liberty.

Mary Ellen’s French reading shows her wit and intelligence, but also her guilt and anxiety. Johnson thinks of her as seeking “self-respect and justification.” Inevitably, there are a lot of biographical “perhapses” and “we can only guess” and “must haves” as she tries to put the record straight in her subject’s favor from rather little evidence. She argues that Mary Ellen didn’t abandon Arthur, but that Meredith took the child away and tried to keep him from his errant mother, as Karenin did with Sergei. Later, Johnson shows Meredith as cruelly neglectful of Arthur, who predeceased him at the age of thirty-seven and whose funeral Meredith didn’t attend. Mary Ellen and her lover didn’t recklessly dash “off to Capri,” as legend had it, but went quietly to stay in Wales and only later to the Continent so he could paint there. Wallis didn’t leave her (as has been said): they went to ground for the sake of discretion, while she had their child.

Since Johnson first published her book, some more letters to and from Mrs. Meredith, and a short memoir by her close friend Anne Ramsden Bennett, have been discovered and published. These documents endorse Johnson’s version of Mary Ellen (though casting slight doubt over how poorly attended her funeral was). They also give a few more chances to hear Mary Ellen’s voice, firm and sharp in a letter to some unsatisfactory publishers over a projected cookbook reissue (“You had better make up your mind about the editions and the copyright and let me know”), tender and sweet in a note to four-year-old Arthur, enclosing some primroses and some “little books”: “Good bye my own Goldens. Here are ten kisses xxxxxxxxxx and coozles and cuddles from your own mother.”

Though gossiped about, vilified, and, after Felix’s birth, very unwell with kidney disease, Mary Ellen kept up an “equable and independent” tone in her letters. By her fortieth birthday she knew she was dying. Early on, she had asked in her commonplace book, “Will that young girl be true to herself?” Johnson concludes that she had been. In the list of characters with which she ends her book, she sums up her vividly reconstructed heroine as “an unfortunate but courageous woman.”

Johnson argues that it was “more possible to be a clever, strong-minded woman with beliefs in the eighteenth century than it was in the nineteenth.” She sees Mary Ellen’s true “ancestresses” as Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughter Mary Shelley—who knew the Peacocks well. She presents her unfortunate heroine as an eighteenth-century woman born into the wrong historical moment. And she has it in for “the Victorians,” a term she uses throughout for everything bad: sexism, chauvinism, hypocrisy, conventional conservatism. The Victorians thought that “women were…inferior,” should be kept narrowly educated, and should be “innocent, unlearned,” and “motherly.” Victorian women had to resign themselves after marriage to endless childbearing (and deaths of children), had no rights, and hardly ever left their husbands. She derides the prudish Victorian biographers who endorsed such attitudes and who tell Mary Ellen’s story as though “death were the deserved fate for Victorian wives who broke the rules.”

Johnson enjoys herself with this broad-brush, caricaturing version of the nineteenth century (“Everyone had headaches, and lay about on sofas”) and goes in for lots of ironic “of courses”:

Of course, as every Victorian knew, if you have sinned you cannot, cannot possibly, expect to die surrounded by your family and friends. Victorians knew these things; they rearranged facts to fit with what they knew.

The tone, which feels a bit heavy-handed now, was part of her defense of Mrs. Meredith as a misfit in her time—and unfairly involved burlesquing Meredith himself as a typical Victorian. But that burlesque matches the book’s ebulliently novelistic methods. One of its interesting arguments is over the relation between biography and fiction. These considerations are buried, rather oddly, in long polemical footnotes, as though there are two parallel books being written at the same time, one telling the story and one commenting on its implications, in the manner of Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas. Johnson says of biography, in her footnotes, “In a sense it is fiction…. As far as the reader’s responses are concerned, there is finally very little difference.”

This is a novelist’s biography, and she goes about it boldly and inventively. It’s full of vivid fictional scenes and imagined inner lives. There’s the little girl playing outside her cottage who gets abducted by the “mad” Jane Peacock and whose whole life is entered into for one page before we lose sight of her forever. There’s wise Edith Nicolls, who learns early in life “the way [people] had of running off, and dying, and being sad.” There’s poor Arthur Meredith, repeatedly ordered by his father not to cry and to be a “little man,” sent away to school, replaced by Meredith’s second family, and banished abroad: “He didn’t mind a lonely voyage—he was used to strange places and strange faces.” There’s a made-up scene in which Meredith as the “venerable, testy” grand old man loses his temper with an interviewer who asks about his first wife, then gives his distorted version: “A sad affair. She was mad, you know. Madness on her mother’s side of the family. And she was nine years—nearly a decade!—older than me.” And, throughout, there are the voices of anonymous people talking—onlookers, gossips, prudish commentators: “She just up and went—but it is bad when your wife leaves you; it reflects on a man.” “Fascinating woman; very charming; very brilliant, no doubt—but you’re better off with a nice, old-fashioned girl.”

As a novelist, Johnson knows all about gossip and the pressure of social conventions. She knows, too, about selfishness, bad behavior, failed marriages, illicit desire, and illusions. A worldly French woman novelist (and terrible mother) in Le Mariage (2000), one of Johnson’s dazzling comedies of American-French relations, has “the dim view of human character natural to her and to novelists in general.” Johnson said of herself in Flyover Lives that being a “petite” woman and therefore often treated like a child long after childhood, she developed “judgmental, observant habits of mind.”

Her mature novels are sharp-tongued and sharp-edged, penetrating about small groups of people at odds with one another—often expat West Coast Americans and the French upper classes in Paris. She is an expert on evasions and bad faith. Lulu in Marrakech (2008) begins with the narrator, a “human intelligence” agent, considering “self-deception” and whether Americans are the most prone to it. Johnson is especially good at women talking to themselves, often not very coherently, about their lives and what has gone wrong with them. Here is a middle-aged woman, in a novel set in a hospital:

What was happiness anyway? Could you pursue it, or did you merely have it within you, like a virus that could pop out at any moment or lie dormant?… You heard people talk of finding happiness, but you never heard them talk about how it can be lost.

Here is an unobservant American away from home, with a wobbly marriage and an elusive lover, beginning to realize that she hasn’t been concentrating:

You seldom get to do anything you believe in, for something you believe in, she thought. Life requires no decisions and no actions from a person like her…. She wondered if she ever felt things enough. Too much? What was the appropriate amount of self-concern?

Here is an actress turned châtelaine of a big French house, married to a selfish film director: “She thought of herself as having made a mistake in life. She had no particular name for it, just a mistake.” Often these women aren’t paying quite enough attention to their own lives—and, as they learn in Le Divorce, “the smallest moment of inattention turns out to be the most disastrous.” But Johnson is paying attention, all the time.

And she was very well placed to pay attention to the ordeal of Mrs. Meredith. In her memoir she describes growing up in Moline, Illinois, in the 1930s and 1940s and leaving the Midwest at nineteen, first for New York (where in 1953 she was part of the same cohort of writers talent-spotted by Mademoiselle magazine as Sylvia Plath) and then, after marrying at nineteen, for California. She had written a few light novels of California life by the time she started work on Lesser Lives; her marriage, meanwhile, had ended, much to her relief (it boiled down to “not liking each other”). She went to England to research her book, working in the British Library while bringing up four children on her own. Mrs. Meredith, who had left her husband and who defied convention “to run off with a lover,” felt like an inspiration and a friend.

Then came her long second marriage to a distinguished physician (who died this March of Covid-19), a life split between San Francisco and Paris, and some movie work, including writing the script for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. With Lillian Hellman’s cooperation she wrote a biography of Dashiell Hammett (she loves thriller plots and detective work in her novels, and knew all about Hollywood). From the 1980s to the late 2000s she had a run of successful novels. Her fascination with clashing “customs of the country” (Le Divorce, for instance, is hilarious on every detail of American/French differences, from scarf-wearing, smoking, food-serving, and present-giving to sex, infidelity, politics, and family life) places her in the grand tradition of Henry James and Edith Wharton. And her lifelong interest in women’s choices and social treatment puts her, ironically enough, in a line of fictional descent from George Meredith. When an old feminist novelist in Le Divorce says of women that they are “not usually considered independent moral beings…except where sexual transgressions are concerned,” she sounds just like him.

That’s probably not a connection Johnson would relish. Though she acknowledges Meredith’s brilliance, she presents him as a bitter, vindictive, and ungenerous human being. She identifies him with his “Egoist,” Sir Willoughby, desperately struggling to conceal his “personal humiliation” from the world. She calls Modern Love a “face-saving” exercise. And she doesn’t think much of the way he keeps turning Mary Ellen into the beleaguered “femmes du monde” in his novels, treating this as a punitive, obsessive return to unfinished business rather than as evidence of his “championing of women.” What she wants to point up is the shocking disparity between his personal behavior to Mary Ellen and her son and the “ability to understand and portray women” for which he was so much praised.

But George Meredith, now, is more in need of resuscitating than vilifying. He himself has become a somewhat obscure life. His satirical investigations of what Woolf, in one of several essays on him, called “the extremely complicated comedy of English civilized life” made him famous from the late 1870s onward. For his last thirty years he was an eminent literary grandee. In old age, stone-deaf and immobile, living in Box Hill in Surrey, he became a destination for literary pilgrims, to whom he held forth at length, unable to hear anything they were saying but delighted to be visited. Wharton was taken to the shrine by James in 1908 and was thrilled to find that Meredith was in the middle of reading one of her books. She watched the two distinguished old friends with admiring pleasure as Meredith’s “great bright tide of monologue” poured out.

Virginia Woolf, twenty years younger than Wharton, had a more mixed view of him. Meredith was close to her father, Leslie Stephen—he used Stephen as a model for the mountaineering tutor, Vernon, in The Egoist—and in her youth, when she started reading him, she thought of him as a living classic. In the 1910s she and her Bloomsbury friends read him with avidity: like Samuel Butler or George Bernard Shaw, he seemed to them an anti-Victorian Victorian, challenging the hypocrisies of his time through laughter and irony, and the conventions of the novel with “high emotional excitement” and “flamboyancy.”

“Meredith pays us a supreme compliment,” Woolf wrote. “He imagines us capable of disinterested curiosity in the behaviour of our kind.” Diana Merion, the gallant heroine of Diana of the Crossways, witty, clever, brave, and branded by society (closely based on the Irish playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s granddaughter the novelist Caroline Norton, a famously dazzling talker), was their ideal, with her bold way of speaking for women:

I suppose we women are taken to be the second thoughts of the Creator; human nature’s fringes, mere finishing touches…. [But] give us the means of independence, and we will gain it, and have a turn at judging you, my lords! You shall behold a world reversed.

But by the 1920s Meredith felt to Woolf, E.M. Forster, and other writers of their generation too strident and shallow and insistent. His “flamboyancy” was now an irritation. Tastes had changed, and “the partition between us is too thick for us to hear what he says distinctly.”

When Meredith died in 1909, he was still considered so radical (and un-Christian) in his views that the dean of Westminster wouldn’t allow him to be buried at Westminster Abbey. But there was a memorial service for him there, and many writers (and attendant autograph hunters) went to his funeral in Dorking. Thomas Hardy wrote a poem in his memory and J.M. Barrie an essay, and all the local suffrage societies, which he had supported, sent wreaths. The Times called him “the greatest man of letters of his age.”

And now, who reads George Meredith? In 1997 the critic John Sutherland described him in the TLS as “to all intents and purposes a literary corpse.” There have been attempts to revive him: Virago claimed him as a feminist writer with a reissue of Diana of the Crossways in 1980, Oxford World’s Classics published a new edition of The Egoist in 1992, and his novels and essays crop up regularly in books about the “New Woman” or the Comic Tradition in English Fiction. Modern Love features in courses on Victorian poetry. There may be Meredith fans reading this now, who will passionately leap to his defense. One distinguished Irish historian friend tells me that The Egoist would be his Desert Island Discs book. But I suspect that’s a rather unusual choice.

There stand the fat, fusty, dusty books in their red-and-gold bindings, with their florid titles—The Shaving of Shagpat, One of Our Conquerors, The Amazing Marriage, Lord Ormont and His Aminta. If you take them down and open them, someone is talking at you, at high voltage, in a voice of rococo elaboration and laborious irony: about the Comic Spirit, or the English Yeomanry, or the march of Commerce. There are elephantinely playful first-chapter titles like “I Am a Subject of Contention” or “A Chapter of Which the Last Page Only Is of Any Importance.” There are characters called Diaper Sandoe and Hippias Feverel and Sir Lukin Dunstane and Countess Fanny of Cressett. There are paragraph-long metaphorical sentences that make Proust and late James look simple.

You have to take a deep breath before you plunge in, and it takes a while to get hooked, if you ever do, on the ruthless analysis of hypocritical behavior, social forms, and class prejudice, the bold exposés of cruelty and narcissism, the prickly, tense, insulting dialogue, the sexuality roaring out through thickets of repression, and the intelligent women struggling in anguish for independence and fair treatment. But those stories mostly lie neglected now. Diane Johnson might well feel that justice has been done. The whirligig of literary reputation has brought about its own revenge, true to the Comic Spirit of irony that Meredith so often invoked.