Although I have not visited the graveyard in the French town of Sète that is the subject of Paul Valéry’s extraordinary poem “Le Cimetière Marin” (“The Cemetery by the Sea”), I know of a counterpart at the opposite end of the Côte d’Azur, on the Italian border, in Menton. Both cemeteries perch above the Mediterranean, their tombs and mausoleums white and gold in the sun, stretched before them the infinite, ever-changing ocean, and above, the vast, eternal sky. To read Valéry’s poem—published in 1920, when he was almost fifty—is to be transported to the landscape of his birth:

This peaceful roof of milling doves

Shimmers between the pines, between the tombs;

Judicious noon composes there, with fire,

The sea, the ever-recommencing sea…

To read it is at the same time to inhabit, with the poem’s narrator, the anguished desire to renounce attempts to transcend death in favor of its acceptance, and to embrace mortal life—“The wind is rising… We must try to live!” The poem’s epigraph, from Pindar—“Do not, O my soul, aspire to immortal life, but exhaust what is possible”—distills its meaning; but the poem itself, exhilarating as the rising wind, evokes both classical echoes and the immediate, visceral experiences of the aging artist in the face of finitude.

“Le Cimetière Marin” remains the most popular and perfect of Valéry’s poems, perhaps because its metaphysical meditations are grounded enough in the natural world for the reader to apprehend them. For bringing this poem alone to a new generation of Anglophone readers, Nathaniel Rudavsky-Brody is to be commended; but with The Idea of Perfection: The Poetry and Prose of Paul Valéry, he has done more. He has made newly available, in assiduously balanced and nuanced translations, all the significant poems of this now overlooked titan of French letters, and along with them, rousing extracts from Valéry’s extraordinary, posthumously published notebooks.

Surely one reason Valéry’s literary reputation has languished among English readers is the near impossibility of successfully translating the work of a poet who strove for what he called “la poésie pure”—his theory, influenced by the Symbolists, of an autonomous poetic language that relies on sound over signification. “Le Cimetière Marin” is atypical in the groundedness of its narrative voice. Valéry elsewhere relied more heavily on inanimate or mythical subjects—goddesses, statues, even plants—frequently deploying them in service to the poems’ formal and musical structures. A stanza from “Palm” illustrates the translator’s predicament:

N’accuse pas d’être avare

Une Sage qui prépare

Tant d’or et d’autorité:

Par la sève solennelle

Une espérance éternelle

Monte à la maturité!

Rudavsky-Brody’s faithful and meticulous translation reads:

Don’t blame for being selfish

A Wisdom that’s preparing

Such gold and authority:

Eternal hope is climbing

Through solemn lines of sap

To reach maturity!

This is, in English at least, almost nonsensical. How can wisdom be selfish? How can sap be solemn? What are the gold and authority here? Though the poem’s meaning in French is not much clearer, the music of the language creates its own sort of sense, and does so in a way that seems almost to wink at the reader. The assonance and end rhymes (all the a’s of “accuse,” “pas,” “avare,” “Sage,” “prépare”) and the alliterations that follow in the second half of the stanza create a linguistic texture that through sound evokes the palm tree that is the poem’s subject: “Tant d’or et d’autorité” seems almost a homonymic pun; “sève solennelle” and “espérance éternelle” give us first a sibilant singsong, and then an echoing whisper that moves from the s of “espérance” to the t of “éternelle.” And this is not to touch upon the scansion; forms were, for Valéry, crucial and complex. In French, many registers operate concurrently to create the poem; in translation it is impossible to capture them all.

One sees this challenge most acutely in Valéry’s celebrated and enigmatic long poem La Jeune Parque. Regarded as the work that marks in French poetry the shift from the nineteenth century to the twentieth, it occupies a position similar to T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land in English. It is layered with allusion and wordplay; in it Valéry compressed various classical myths and recombined them with the work of French literary masters from Corneille to Mallarmé. The poem’s title translates as “The Young Fate” and refers to Clotho, the youngest of the three Fates and the spinner of destiny. The narrator of the poem, she stands at the seashore, bitten by a serpent, and contemplates mortality and immortality, addressing, among many others, her own divided self: “And yet, mysterious ME, you’re still alive!”

Advertisement

The poem is also a meditation upon consciousness and self-consciousness, upon history and language, upon the relation of the subjective mind to the external world. Yet as Edmund Wilson pointed out long ago in Axel’s Castle, themes are never fully clarified: “The picture never quite emerges; the idea is never formulated quite.” This obscurity is deliberate: Jacques Derrida observed that “what Valéry intends to resist is meaning itself.” The poem was begun in 1912 and written during World War I. Valéry later wrote of that time, “I saw myself as a fifth century monk who knows that all is lost, that the monastery will go up in flames, and the barbarians will destroy everything. No one will see his work.” Its hermeticism is almost ironic, just as Valéry’s determination to write in rigid alexandrines (the traditional form of French poetry) seems a commentary on the lost classical traditions from which he and his times were being forcibly ruptured by the war and the dissolution of European culture as he understood it.

Like Eliot’s, Valéry’s vision is one of loss and lamentation: “I am filled with the light of horror, foul harmony!/Each kiss is presage of new deaths…I see,/Floating, fleeing the honors of the flesh,/The bitter millions of the unmanned dead…”; “Will he who finds my footprints in the sand,/Alas, stop thinking of himself for long?” Unlike Eliot, however, whose visions of dissolution and decay are rendered at least partly within the quotidian world that he and his readers inhabited (“Mr. Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant…/Asked me in demotic French/To luncheon at the Cannon Street Hotel/Followed by a weekend at the Metropole”), Valéry situates his statuesque Fate in a landscape that, while nominally of this world, is outside the specificities of place and time, and therefore remains abstracted, limning metaphor in every moment. When “With vibrant wood bent down beneath its height,/The tree united rowing for and against/The gods, a floating forest whose rough trunks/Piously draw to their fantastic brows,/To the sad farewells of splendid archipelagos,/A stream that flows, O Death, under the grasses?,” the reader may be hard pressed to grasp what, exactly, Valéry intends—fact or fantasy? Which, of course, is the point.

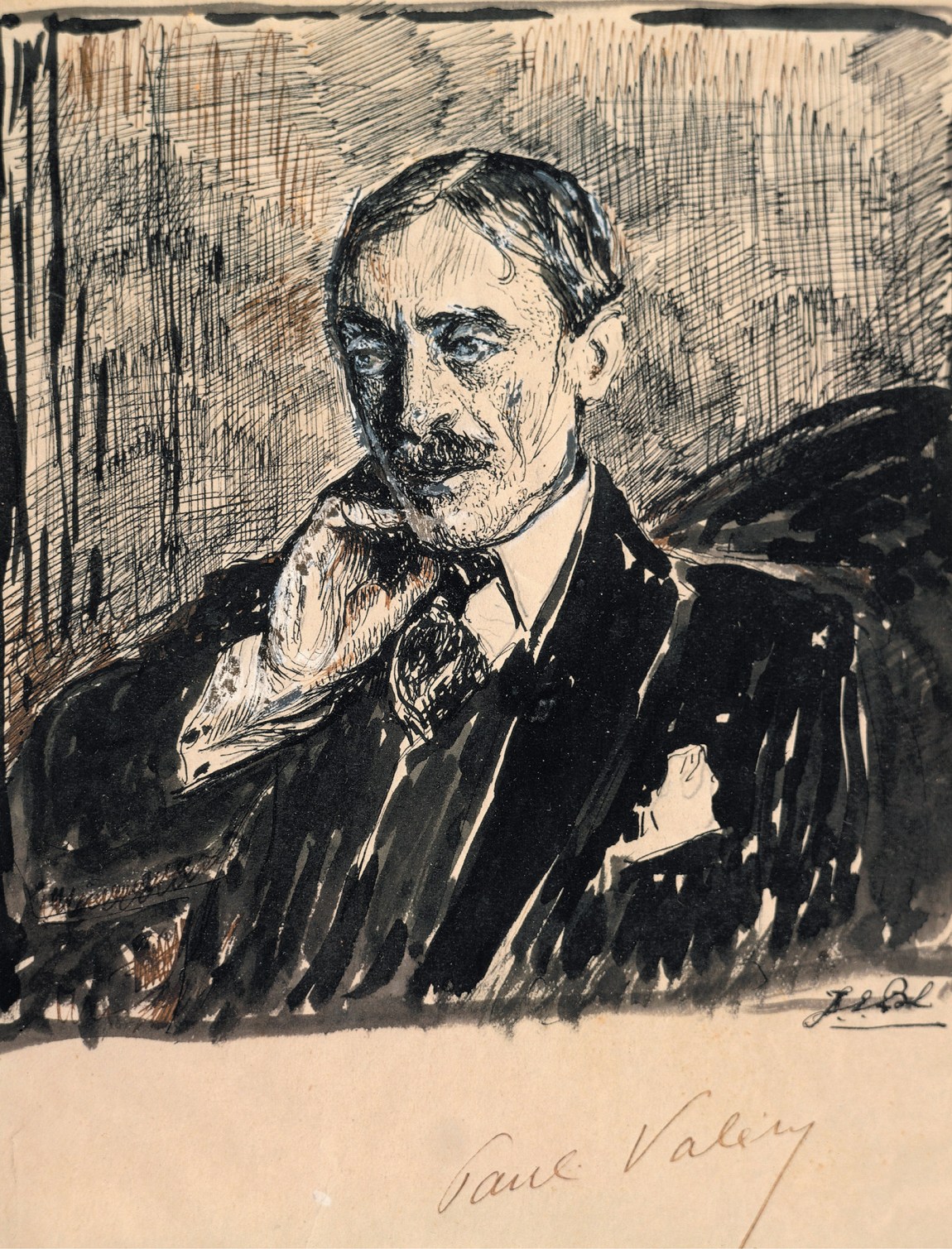

Born in 1871, Paul Valéry grew up in Sète and Montpellier in the south of France. In 1890, when he was a law student in Montpellier, he befriended Pierre Louÿs and, through Louÿs, André Gide. Louÿs also introduced him to the Parisian literary circle of Mallarmé, whose work Valéry revered. Mallarmé was the leading figure of Symbolism, the movement in French poetry—highly metaphorical, deliberately esoteric—that had turned away from traditional French classicism and clarity in favor of indeterminacy, synesthesia, and an emphasis on the musicality of language. With the help of these powerful friends, Valéry published a number of poems over the next two years, making very early his mark on the French literary scene.

But following a spiritual crisis in 1892—what he called his “Nuit de Gênes” (Night in Genoa)—he turned away from poetry and published not a single line for twenty-five years. Fascinated instead by the sciences, he wrote a book on Leonardo da Vinci (1894), and his novel Monsieur Teste (1896), about a pure intellectual who has dispensed with all practicalities in order to live in his head (hence his name, a play on tête). This parodic character has about him aspects of his creator.

Throughout the period of his poetic latency, even as the world around him changed dramatically, Valéry’s aesthetic program—heavily influenced by Edgar Allan Poe, who was important also for Mallarmé—did not fundamentally alter: he wrote in 1939, “In sum I do nothing but redraw what I thought with my first intentions.” He eventually returned to poetry at the urging of Gide; La Jeune Parque, which he described as “an autobiography in form,” was published in 1917. This, along with two subsequent slim volumes, Album of Early Verse (a reworking of his early poems, published in 1920) and Charms (1922), swiftly made him a literary star. As his biographer Benoît Peeters observes, “there are only seven or eight years between the publication of La Jeune Parque and the consecration of Valéry as ‘the greatest living poet’ and a member of the French Academy.” He became “a sort of official poet” (“poète d’État”), which would prove perhaps a trap both for the author himself—Mallarmé, his mentor, firmly resisted the imprimatur of the establishment—and for his readers.

Advertisement

Rudavsky-Brody’s versions of Valéry’s poems are often beautiful and in places inspired. Insofar as is possible, he brings Valéry’s difficult syntax and diction into an English that, if not always familiar, is certainly accessible. Here are the opening lines of La Jeune Parque, followed by his translation:

Qui pleure là, sinon le vent simple, à cette heure

Seule, avec diamants extrêmes?… Mais qui pleure,

Si proche de moi-même au moment de pleurer?

If not the wind, then who is crying there

At this lone hour with farthest diamonds?…Who

Is crying, so near me at the moment of tears?

And here is David Paul’s translation of 1971:

Who is that weeping, if not simply the wind,

At this sole hour, with ultimate diamonds?… But who

Weeps, so close to myself on the brink of tears?

Both require careful parsing, and some leeway with the figurative, but Rudavsky-Brody at least lowers the rhetorical grandeur (from “weeping” to “crying”; from “ultimate” to “farthest”) and brings both diction and syntax closer to contemporary American English.

Even with these fine new translations, it is unlikely that a broad Anglophone readership will flock to Valéry. But Rudavsky-Brody’s undertaking is a testament of faith in Valéry’s importance. Insofar as he endures in the public imagination at all, it is as the bridge, in French letters, between the Symbolists of the late nineteenth century and modernism. Eliot asserted that Valéry would “remain for posterity the representative poet, the symbol of the poet, of the first half of the twentieth century—not Yeats, not Rilke, not anyone else”—an irony, given that Eliot has assumed that position while Valéry has been largely forgotten.

Many of Valéry’s poems—filled with images of glimmering moons, dark woods, and foaming waves; peopled by white-limbed maidens, sibyls, sylphs, nymphs, Fates, Narcissus, and the Pythia—may feel of primarily historical relevance now. But his essays on literature and politics, as well as his vast lifelong private endeavor, the Notebooks—of which there exist almost 27,000 pages, on which he worked daily for much of his life and uninterruptedly during the years in which he did not publish—are as clear and effective as when they were written.

Still, the theoretical expression of his poetic intentions spoke powerfully to Valéry’s peers and successors. His essays, mostly written in the 1930s and collected in The Art of Poetry (1958), had a wide and lasting influence. Eliot wrote, “My intimacy with [Valéry’s] poetry has been largely due to studying what he wrote about poetry”; and Yves Bonnefoy, while qualified in his admiration for the poetry itself, recalled his youthful devotion to Valéry’s lectures at the Collège de France, because

this poet, who was concerned with the obscure regions of the word, was also an essayist, a thinker, whose explicit intention, served by great talents, was to master the problems that poetry poses for the spirit.

Even among poets, Valéry’s primary importance may have been as an essayist.

One classic formulation of la poésie pure appears in his essay “Poetry and Abstract Thought,” given as a lecture at Oxford in 1939 and included in The Art of Poetry. Here, Valéry explains that poetic language “is a language within a language,” and proposes that the difference between prose and poetry is like that between walking and dancing. Prose, he says, is purely utilitarian: it is language serving a function, the way walking serves to move a person from one place to another. In prose, words disappear into their meaning and cease to exist on their own account—the aim of language is to be transparent. Poetry, meanwhile, is like dance, a movement that serves no function beyond itself, and indeed calls attention only to itself. In poetry, sound and music are more important even than what the words signify: in Saussurian terms, poetry attends to the signifier rather than to the signified.

Unlike Eliot, Valéry viewed thought and feeling as distinct, and sought to balance them in his work: “I think as a totally pure rationalist. I feel as a mystic.” He aimed to deploy language without the distortions and mediations of convention or society. In order to attain this elevated state—and more broadly, in order to write genuinely—

one should give up the practice of considering only what habit and the strongest of all habits, language, present for our consideration. One should try pondering other points than those suggested by words, that is to say, by other people.

This might involve seeking to address prelinguistic or extralinguistic experience—whether sensory or abstract—and finding ways to articulate that experience using words while relying, as much as possible, on structural or phonic elements that transcend the conventional meanings of those words. To render experience as purely as possible, in all its complexity, will involve loosening the reductive bonds of conventionally agreed-upon meaning, widening the space between the signifier and the signified.

Valéry was acutely conscious of the ways that time distorts historical expectation and literary convention. In writing about La Fontaine’s Adonis, he acknowledged that “the reader of today is very remote from the reader of 1660…. Let us not imagine that we are reading the very same poem as the author’s contemporaries.” Although only a century has passed since Valéry wrote, the same is true for us: the aspects of his oeuvre that may speak to us now will perforce be different. As for the effect of society, he expresses the paradox thus:

Literature exists first of all as a way of developing our powers of invention and self-stimulation in the utmost freedom…. But this fine prospect is at once clouded by the necessity of influencing an ill-defined public…. However the enterprise may end, it involves us in dependence on others, and the state of mind and the tastes we attribute to them thus insinuate themselves into our own mind…. Without realizing it, we abandon all extremes of severity or perfection, all depth of thought that is not easily communicable, we pursue only what can be brought down, we conceive only what may be printed.

In the poems, he sought to disregard, or transcend, society’s deformations, and perhaps thereby the effects of time as well. But in his commissioned essays, which he disparaged as “forced labor,” he condescended to address his peers and expressed insights that remain fresh and valuable today. Although none are included in Rudavsky-Brody’s anthology, Valéry’s essays on poetry alternately feel historically illuminating and oddly contemporary. He writes, for instance, about how, “since the invention of ‘sincerity’ as valid literary currency,” confession has become “as good as an idea”—a rebuke that anticipates not only the confessional poetry of the later twentieth century but also our more recent preference for memoir and opinion over rigorously developed and substantiated ideas.

The political essays remain relevant: in 1931, almost twenty years before the forerunner of the EU was established, Valéry advocated for a united Europe:

History will never record anything more stupid than European competition in politics and economics, compared, combined, and contrasted as it is with European unity and agreement in matters of science.

In the same essay, he anticipated the later theories of the historian Fernand Braudel, known for his concept of longue durée, writing that “there is nothing easier than to point out the absence, from history books, of major phenomena which were imperceptible owing to the slowness of their evolution.” In his 1935 speech “Le Bilan de L’Intelligence,” we can recognize our present day in Valéry’s account of his:

Interruption, incoherence, surprise are the ordinary conditions of our life. They have even become veritable needs for many, whose spirits are only nourished by brusque variation and endlessly renewed excitements. The words “sensational,” “impressive,” that we use so frequently today, are the words that encapsulate the period. We no longer have any endurance. We no longer know how to be inspired by boredom. Our nature is horrified by emptiness.

This essay in particular, in which he addresses the risks of living ahistorically—that is to say, in the misguided apprehension that the present is “a state without precedent or example” (“un état sans précédent et sans exemple”)—has powerful echoes for us, knowing as we do that it was written only a few years before the start of World War II. That may explain why not long ago it was reprinted in France, where, sadly, as Peeters has lamented, “Valéry’s star has done more than fade. He is no longer read, except in a few university departments. It seems that nobody even thinks of him.”

I’m mystified that we no longer read Valéry’s essays, which are as important as Eliot’s or Orwell’s, and can only attribute this to the reputation for difficulty and obscurity—flowing from his poetry—that has clouded his legacy. Difficulty is unfashionable; so too is Valéry’s hermetic poetic vision, which Eliot acknowledged in 1948 “has gone as far as it can go. I do not believe that this aesthetic can be of any help to later poets.” La Jeune Parque is perhaps to poetry what Finnegans Wake is to fiction: a modernist cul-de-sac.

After 1924 there was no more poetry. Valéry explained:

Nothing so pure could coexist with the conditions of life. We cross the idea of perfection the way a hand, with impunity, crosses a flame; but you cannot live inside the flame, and the homes of the highest serenity are necessarily abandoned.

Yet there is another realm of Valéry’s work that has remained essentially outside public view, the lifelong endeavor that should bring his intense and meditative spirit to a contemporary readership. “Hide your God,” Valéry famously wrote, “for as He is your strength, in that He is your greatest secret, He is your weakness as soon as others know Him”; it is in his Notebooks that an otherwise unseen strength emerges.

In these pages—the enormous project that he described to his friend Paul Souday as “my real oeuvre”—Valéry pursued the aesthetic project of a pure expression, unadulterated by the demands of communication: “The idea of another reader is entirely absent from these moments.” Sometimes he wrote in poetic form, but often in fragments or fully in prose. The extent of these extraordinary documents was not known until after his death.

Valéry’s literary legacy may be like the Roman mosaic recently discovered beneath an Italian vineyard, culturally defining but not presently alive. But the relation of his Notebooks to his published work is more like that of the vineyard’s root system to its vines: they underpin and allow—they create, in fact—everything of which Valéry’s reputation consists. The Notebooks are the record of a sentient body and its experiences in the world; of a mind and its thoughts; and of the rich encounters of the two. Whereas today Valéry the poet seems all too often bound by a classical, even abstruse iconography and syntax, and whereas Valéry the essayist may seem to some readers dry, the Valéry of the Notebooks—or at least of the glimpses from them that Rudavsky-Brody includes in this anthology—is wise and fiercely honest, self-aware and keenly observant of the world.*

Reading these extracts, I kept wanting to share them: this is how a writer lives, sees, thinks; here is the humility, the curiosity, the astonishment that endlessly renews our days. Here are a few examples, each direct, intimate, grounded, and utterly evocative:

Complete Poem

The sky is bare. The smoke wafts up. The wall is bright.

Oh, how I want to think clearly!

All books seem fake to me—, I have an ear that hears the author’s voice,

I hear it distinct from the book—They are never united.

And I saw, above all, the value and the beauty, the great excellence, of everything I have not done.

Here is your oeuvre—said a voice.

And I beheld everything I had not done.

And I saw more clearly than ever that I was not the one who has done what I have done—rather, I was he who has not done what I have not done—What I have not done was therefore perfectly beautiful, in perfect keeping with the impossibility of being done.

And, of the dawn, that daily rebirth of the self of which he wrote frequently:

I feel so strongly at this hour…the depth of appearance (I can’t quite express it) and that is poetry. What speechless wonder that everything is, and that I am! At this moment, what we see takes on the symbolic value of the sum of all things.

These words, addressed to no one but himself, live as fully now as when he wrote them, and even the superabundant formlessness that is the Notebooks’ nominal failing speaks, in these times, to our overwhelmed condition. To cite Eliot, “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.”

-

*

For a larger selection of Valéry’s Notebooks, based on the Pléiade edition of the Cahiers edited by Judith Robinson-Valéry (Paris: Gallimard, 1973–1974), see the five-volume Cahiers/Notebooks, edited and translated by Brian Stimpson, Paul Gifford, Robert Pickering, Norma Rinsler, and others (Peter Lang, 2001–2010). ↩