Not all liberations are complete. For the Korean peninsula, the end of World War II brought freedom from Japan’s colonial rule, but it also sliced the territory in two, a division made permanent by the subsequent Korean War. This was no Korean’s postcolonial dream: the North, under Soviet backing, went to Kim Il-sung, who’d gained renown as a guerrilla fighter; the South, occupied by the United States, went to Syngman Rhee, an aging expatriate with Ivy League credentials. North Korea’s loyalty oaths and prison camps soon became well known, but South Korea, too, was for decades a democracy only in name. Rhee and his men—who saw themselves as foot soldiers in the global war on communism—ruled with junta-like violence, killing leftist dissidents and unification activists perceived as a threat to the new government.

For much of the postwar period, members of a once large, diverse South Korean left wing espousing Marxist and anarchist views were viewed as North Korean sympathizers and targeted for elimination. In the late 1940s South Korean military forces, with the knowledge of the United States, killed as many as 60,000 civilians on Jeju, a southern island governed “by strong left-wing people’s committees,” according to the historian Bruce Cumings. The repression continued nationwide after the Korean War. But by the 1970s, a democracy movement called minjung (literally, “the people”) began to rise up against Rhee’s eventual successor, General Park Chung-hee. Minjung radicals, concentrated among factory workers and students, pressed for free speech and political representation. Thousands of citizens rallied and marched, through teargas and bullets, and defied curfews and state censors.

They also studied leftist literature, much of it written in English and Japanese. As Han Hong-koo, a minjung veteran and popular historian of modern Korea, told me in Seoul two years ago, reading in those days felt like a matter of life and death—and ideological calisthenics. Of all the books that gave him and his comrades access to a recent, radical past, the most important was Song of Arirang: The Story of a Korean Revolutionary in China, a memoir as told to the journalist Helen Foster Snow.

First published in 1941, the book tells the story of a Korean colonial-era revolutionary named Kim San. Kim was born in 1905, near Pyongyang, in the north of a unified but colonized Korea. As a young man, he grew so enraged by the abuses of the ruling Japanese, and so inspired by the Soviet and Chinese revolutions, that he traveled hundreds of miles on foot to join the Korean resistance in China and Manchuria. As a teacher and organizer, propagandist and soldier, Kim fought simultaneously for Korea’s independence from Japan and for “the rise of the proletariat” against global imperialism. His story was epic but not singular: the book proved to minjung activists who hadn’t known this history that tens of thousands of other young Koreans had made the same journey.

But the version of Arirang they read was not the original. It was a translation from the English, rediscovered and printed in Korean by the left-wing publisher Dongnyok in 1984. The book passed from hand to hand, “among students, workers, white-collar professionals, soldiers in military barracks—whoever could get hold of a copy before the state authority confiscated bookstore copies,” Namhee Lee, a professor at UCLA, writes in The Making of Minjung. The sight of my own copy from 1984, a gift from a friend, has drawn out the nostalgic reveries of more than a few middle-aged South Korean leftists. To them, Kim represented a near-mythical national hero, a sang namja, or “manly man,” and served to connect minjung to a suppressed revolutionary history. Kim’s life story embodied a range of thrilling contradictions: he proved that an intellectual could shoot a gun, that a leftist (a North Korean, no less) could be a patriot, and that a nationalist could defy borders. In Kim San’s world, Korea was not two walled-off islands, but rather a proud peninsula joined to China, Russia, and Eastern Europe.

Minjung intellectuals were also struck by the story behind the book. Song of Arirang was written not in Kim’s native Korean or fluent Japanese or Chinese, but in English, and not by Kim himself but by Helen Foster Snow, an American woman who had been close to Chairman Mao Zedong in his early days as a revolutionary. Had it not been for her, Kim’s journey and all it represented—the thousands of other Kim Sans in pre-independence Korea—might have been lost.

On the 102nd anniversary of the March First Movement of 1919, a turning point in Korean resistance to Japanese rule, Kaya Press will publish a new edition of Song of Arirang in its original English. It also includes, for the first time, an appendix of Kim San’s political writings, translated from Chinese, and extensive annotations by Dongyoun Hwang, a historian of Korean anarchism. To read of Kim’s life today, amid our clanging nationalisms—in the US, Korea, and all over the world—is to feel chastened by an ancestor of borderless vision. Kim was “a true transnational East Asian,” Hwang told me. “He can’t be owned or monopolized. He must be shared.”

Advertisement

Song of Arirang reads like an adventure memoir, though one stuffed with unfamiliar names, dates, locales, and political jargon. It’s written in the first person, and lists two authors: Kim San, whose real name was Jang Ji-rak, and Nym Wales, the pen name of Helen Foster Snow.

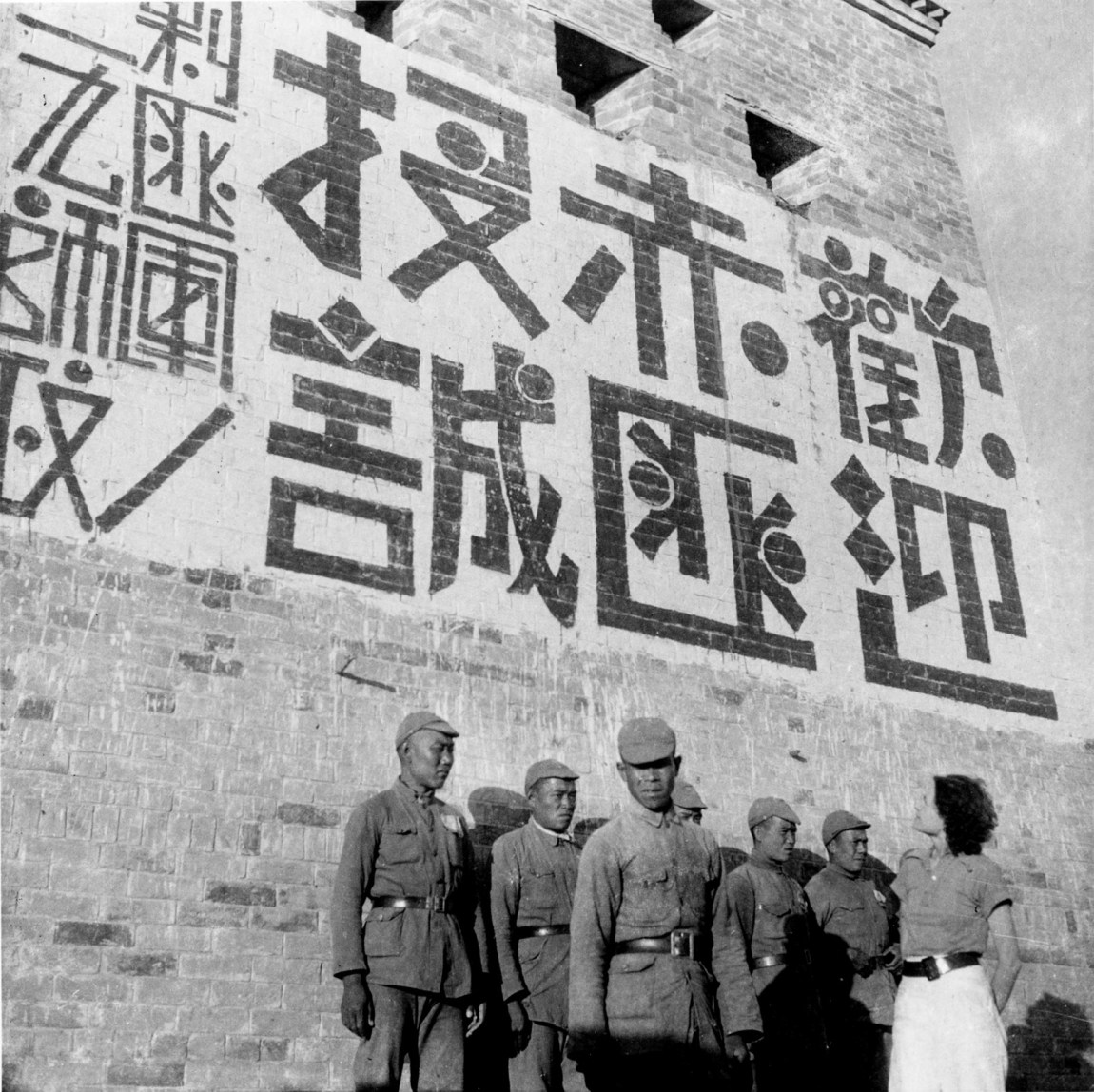

How did Snow, a young woman from Utah, come to write this classic book of the Korean left? She had arrived in Shanghai in 1931, in her early twenties, with dreams of witnessing a revolution in progress and writing a great American novel. She soon began working as a journalist and met and married the reporter Edgar Snow. Their partnership was thrilling but unequal—she often set aside her own work to type her husband’s notes and edit his manuscripts, including for Red Star Over China, the blockbuster first account of Mao and the early Communist Party of China (CPC). In 1937, just before that book was published, the couple had followed Mao to Yan’an, the CPC’s dusty new headquarters in Shaanxi province. During a cease-fire in the civil war between Mao’s Red Army and Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist Kuomintang (KMT), Helen Foster Snow learned of a “Korean delegate to the Chinese Soviets.” She asked the Korean, who called himself Kim San, or “gold mountain,” to sit for an interview.

She was impatient at first, unsure of the project. “I am really afraid I’ll take too much interest in Korea,” she confessed to Kim. “I am always getting involved in lost causes and oppressed minorities.” “Majorities don’t need help,” he responded. “And anyway Korea is not a lost cause.” “He had kept a diary for many years, written in code, and though he had periodically destroyed these notes, it served to fix incidents in his mind,” Snow explains in the introduction to Song of Arirang. They spoke haltingly—he in basic, piecemeal English (e.g., “Guangdong, 1927, defeat, 300 Koreans dead, saltwater”); she in simple questions that imposed story on bare fact. “The breadth of his experiences amazed me,” she writes. “The book was going to cover, not only Korea, Japan, and Manchuria, but the exciting course of the Chinese Revolution as well. Only a wandering Korean revolutionary could have had such broad and differentiated experiences.”

Kim was born during the final months of the Russo-Japanese War, which resulted in Japan’s occupation of the Korean peninsula. At the age of seven, we learn in Song of Arirang, he saw “the dreaded Japanese conquerors” at work: two police officers “came to our house and slapped my mother’s face until blood ran down” because she had not met a deadline to have her children vaccinated. Kim was in middle school when, on March 1, 1919, members of the Korean intelligentsia declared independence from Japan. The following month, expatriate Koreans espousing varied but mostly liberal-democratic views formed a provisional government in Shanghai, as if to ready Korea for independence. And in May, Chinese and Koreans in Beijing led protests against Japan, which had inherited the Shandong Peninsula, in eastern China, from Germany in the Treaty of Versailles.

The Koreans who participated in the March First Movement—including Kim San, who was detained with several classmates for yelling “Man-se! Man-se!,” or “Ten thousand years of independence!”—believed that the West would soon come to Korea’s rescue. President Wilson had promised, after all, in his Fourteen Points, that “the day of conquest and aggrandizement is gone by.” But the US and Europe had no intention of interfering with Japan’s colonial sphere. “Before March First, I had attended church regularly,” Kim says in Song of Arirang. “After this debacle, my faith was broken…. A torment entered my soul and mind. March First was the beginning of my political career.”

Though just a teenager in 1919, Kim resolved to join the nationalist movement in Manchuria, where thousands of Korean soldiers and nearly a million Korean farmers had exiled themselves after the Russo-Japanese War. But first, he explained to Snow, he decided to educate himself—in Tokyo, both an imperial seat and “the Mecca for students all over the Far East and a refuge for revolutionaries of many kinds.” There, Kim studied science and worked odd jobs to survive, theorizing revolution on the side.

Advertisement

He later headed to Moscow, inspired by the work of the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin, but was forced to make a detour on account of warfare in Siberia. He walked some two hundred miles to Manchuria instead, and enrolled in a military school for Korean nationalists. His education there consisted of weapons drills and scrambling up mountains: “What could we not do for freedom? Were there not nearly a million Korean exiles in Manchuria, all eager to recapture their homeland?” In the years to come, while still in his twenties, Kim would join the Communist side of China’s civil war, shuffle between cities (Shanghai and Beijing) and leftist factions (anarchists and Communists), and do whatever else the Chinese and Korean revolutions required. He would study medicine and set up a field hospital, give speeches and write manifestos, form a terrorist cell in an ammunition factory, recruit farmers to the Red Army, and, all too often, have to scavenge for food.

In 1925 Kim arrived in Guangzhou, in southern China, to join the revolution launched by Sun Yat-sen. “All Koreans, right and left, were delighted with this new upsurge in China, considering it the first step in the emancipation of their own country,” Kim says in Song of Arirang. In Guangzhou, he met the British labor leader Tom Mann and Mikhail Borodin, who’d been dispatched by the Comintern, and organized an Oriental League of Oppressed Peoples that included Korean, Indian, Indo-Chinese, and Taiwanese activists. But no sooner did Kim and his fellow revolutionaries begin their march north, aspiring to liberate northern China and Korea, than “the counterrevolution” led by Chiang Kai-shek provoked a full-scale war. Kim stuck with Mao’s CPC, believing that a Communist liberation in China would soon extend to the Korean peninsula.

Chiang’s Nationalists took substantial control of China and established a capital at Nanjing, driving the Reds into hiding. Kim rose to the position of secretary of the local Communist Party in Beijing (no small feat for a foreigner), and assumed responsibility for coordinating “revolutionary activities” among the Koreans and Chinese in northern China and Manchuria. It was dangerous work: “All activities were very secret and underground, as they carried the death penalty,” Kim said.

He was arrested more than once by the KMT police and transferred to Japanese custody in Korea. On one occasion, having barely survived tuberculosis during detention, he tells Snow, he returned to Beijing, where fellow party “members seemed friendly but afraid to meet me.” A Korean rival had spread a rumor that Kim was let out of jail because he was a Japanese spy; Kim was also mistrusted for his ties to a once-prominent CPC leader who had since been ostracized for being too far left, whatever that meant. “I could not avoid feeling that part of my trouble came because I was a Korean among Chinese; even the communists in China had a tendency toward nationalism,” Kim says. He looked back on his ideological journey: he had been a Korean nationalist, then an idealist and anarchist, then a Marxist and—like Frantz Fanon in Algeria or Victor Serge in Russia—a soldier in another country’s revolution. What now?

In 1933 Kim was arrested again, this time by secret agents of the KMT and defectors from the Communist Party. He was imprisoned, then deported to Korea, but returned to China within months. He married a Chinese woman named Zhao Yaping and briefly settled down in Beijing, finding work as a teacher and newspaper editor. But his revolutions called. In the spring of 1935 he went to Shanghai “to renew my contacts with the Korean revolutionaries” and soon established a Korean League for National Liberation under the Korean Communist Party. As a delegate of that league, and with the help of the Red Army, he traveled to Mao’s new headquarters in Yan’an. It was there that he met Helen Foster Snow.

At the end of Song of Arirang, Kim is just thirty-two years old. “Nearly all the friends and comrades of my youth are dead,” he tells Snow, “hundreds of them: nationalist, Christian, anarchist, terrorist, communist. But they are alive to me.” He makes her promise not to publish his story for at least two years, until he is “safely in Manchuria among the Korean partisans.” His wife had informed him of the birth, in April 1937, of their son whom he would not live to see. In October 1938, en route to Manchuria, Kim was reportedly shot to death. The CPC had ordered him killed for being a right-wing Trotskyist and a Japanese spy.

Song of Arirang takes its title from the most popular folk song in Korea—one that predates division by hundreds of years and remains a unifying cultural artifact. It was “Arirang” that played over the stadium loudspeakers as North and South joined forces at the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics. (“Arirang” is a place name with no direct meaning.) Though the tune and lyrics vary by region, they always express a sense of fracture and longing:

Oh, twenty million countrymen—where are you now?

Alive are only three thousand mountains and rivers.

Arirang, Arirang, A-ra-ri-yo!

Crossing the hills of Arirang.

The song appears repeatedly in Kim San’s account to Snow. He recalls singing it on a train while under arrest and surveillance by a Japanese soldier: “I told him the meaning of the song and sang it in a low voice as I looked out over the bare, brown fields.”

Snow lost touch with Kim after their interviews in 1937. She and her husband soon left China, sailing to the resort town of Baguio in the Philippines; they only learned of Kim’s murder years later. In addition to reporting on Mao and the Reds, the Snows had supported a growing student movement in Beijing and helped create a network of industrial worker cooperatives throughout China. As a result, they were in poor health, and Helen suffered from dysentery. In Baguio, she recuperated and completed her manuscript of Song of Arirang, but waited to publish it, keeping her promise to Kim. In the meantime, she published Inside Red China, an account of Mao’s army that she hoped might rival her husband’s Red Star Over China. The book was filled with richly detailed portraits of young leaders, including women, but was dismissed as a mediocre sequel.

In 1941 John Day Company, the New York publishing house run by Pearl S. Buck and her second husband, Richard J. Walsh, released Song of Arirang (as well as a second book by Snow, The Chinese Labor Movement). The reception was positive—the New York Times review called it a “vitally interesting” record of the Korean rebellion, “burning in various strategic points of the Far East”—but the book sold poorly. Buck wrote to reassure Snow that it “was a grand book and I don’t worry at all about the sales.”

Song of Arirang was not translated into Korean until just after World War II, when it appeared in installments in the magazine Shincheonji (New World). Many readers believed that Kim San was a fictional character, and the force of his story receded in staunchly anti-Communist South Korea. It wasn’t until the 1980s that researchers in Korea and Japan verified Kim’s identity. In 1984, when Dongnyok published a new translation of Song of Arirang, the book satisfied a hunger for left-wing historiography. A labor activist named Song Young-in served as the translator, but under a fake name, and for good reason: government censors immediately banned the book, as they did with all things remotely Marxist. (The translation relied on a second English version, printed in 1972 by Ramparts Press; Kaya has incorporated editor George O. Totten’s tireless annotations from that volume.)

Many Koreans have told me how much the book affected them. Jeon Sung-won, a literary critic, called Song of Arirang a “blood-boiling, pep-rallying book” that served to revive “people who were erased.” The historian Han Hong-koo was so taken with Kim San that he wrote a novella about him and tried for years to produce a biopic. Han Sang-gyun, a union leader who was imprisoned for his labor activism between 2015 and 2018, reportedly read and reread the book in his cell.

According to Namhee Lee, Song of Arirang also led to a broader “reevaluation of North Korean literature,” since Kim hailed from Pyongyang. “It was part of lifting the writing by people in North Korea before and after 1945,” she told me. (Another northern writer who contributed to the reevaluation is Kang Kyeong-ae, a pioneering socialist feminist novelist who, like Kim, spent much of her life in Manchuria.) In his memoirs, Kim Il-sung, the founder of North Korea, recognizes Kim San as one of the “tens of thousands of Korean communists and patriots…[who] devoted their lives to the Chinese revolution.”

In 1991 the head of Dongnyok, Lee Geon-bok, contacted Helen Foster Snow. By then she was well into her eighties and living in Connecticut. When he told her that he was planning to reissue the 1984 translation, it was the first she had heard of the Korean version of Song of Arirang and its impact on a generation of leftists. She agreed to contribute a short afterword. In it, she thanks Dongnyok and the Korean people for rescuing the book from obscurity. “This is how I would describe Kim San,” she writes: “he was someone who possessed the spirit and psychology of a true ‘modern.’”

It took a half-century after Kim’s death for Korea to achieve a democracy, at least in the South. And in 2003, following two liberal administrations, the leftist Roh Moo-hyun, who had represented unionists and students caught with contraband books during the minjung era, became president of South Korea. Extended families blackballed as Communists saw a path back into society. Campaigners for the poor and low-wage workers, as well as censored intellectuals, could relax. Dongnyok published a new, glossier edition of Song of Arirang in 2005, for which the translator Song Young-in felt comfortable using his real name.

The person of Kim San has emerged from this larger history in parallel. China had buried Kim as a traitor, so his wife, Zhao Yaping, kept his identity a secret from their son, Gao Yongguang. She gave Gao the last name of her second husband and told him the truth about his birth father only when it seemed safe—toward the end of the Cultural Revolution, when he was in his thirties, he told the Korean press. (The Kaya edition says he was twenty-seven when he learned of his father’s identity.)

“I first read Arirang in 1981, in a Chinese translation from Hong Kong,” Gao told a reporter in 2002, on his first visit to Korea. “Before that, I’d only heard about him from my father’s old comrades and academics.” Gao twice petitioned the CPC to reexamine Kim’s case and, in January 1983, got him cleared of treason. Gao campaigned for his father in South Korea as well. In 2005 the Roh administration designated Kim San an independence-era patriot.

Roh’s protégé, Moon Jae-in, the current president of South Korea, recently praised Kim as a hero of both the Korean and Chinese revolutions. The Korean revolution, though, is all loose ends, tangling up Moon’s time in office. He has tried to lay out a plan for inter-Korean reconciliation, while refereeing a dangerous scrimmage between President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, and fighting former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe over trade policy and reparations for colonial-era forced labor. The US, meanwhile, still maintains nearly 30,000 troops in South Korea. It is hardly the future Kim imagined.

Since 1984 Song of Arirang has sold some 500,000 copies. To Korean readers, it is both an essential history of East Asian radicalism in the early twentieth century and the diary of an unfinished national revolution. Over the past few decades, the South Korean government has officially recognized around 15,000 people as “patriots,” mostly posthumously, for resisting the Japanese occupation. But many descendants of anticolonial leftists, long dismissed as Reds, continue to seek acknowledgment and compensation. In the poem “Mourning Comrade Han Hae,” appended to the new Kaya edition of Song of Arirang, Kim commemorates the fallen of his own time:

…just how many revolutionaries

Lost their lives in this endless

struggle?

The five thousand wretchedly

fallen French Warriors of the

Paris Commune!

The countless sacrificed Russian

Warriors of the October

Revolution!

The Chinese Warriors who

fearlessly fought in the

Guangzhou Uprising!

When I was last in Korea, I visited the palace-like grounds of Independence Hall, in Cheonan, an hour and a half south of Seoul. The museum charts South Korea’s rise out of feudalism and colonialism into the democratic present. There are wax figurines of March First intellectuals and a room-size tribute to American soldiers, as well as a talking hologram of Syngman Rhee. Yet among hundreds of displays, I counted just two devoted to socialists, anarchists, or Communists—with no mention of Kim San. Korea’s fight for independence remains incomplete, and incompletely told.

This Issue

December 17, 2020

An Awful and Beautiful Light

A Well-Ventilated Conscience

The Oldest Forest