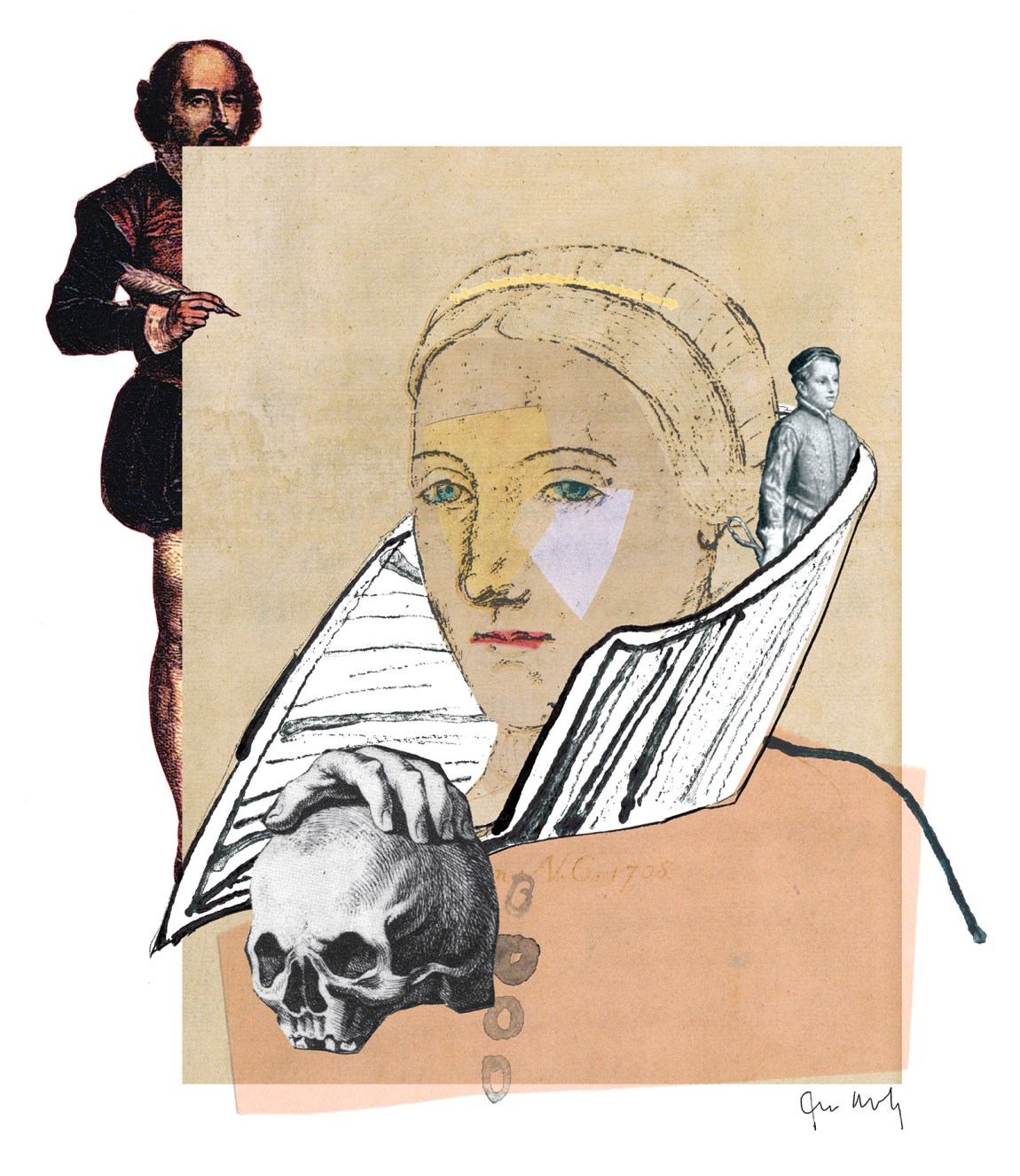

Maggie O’Farrell’s moving historical novel Hamnet is a story of deep loss—the death of a child, struck down by an incomprehensibly virulent epidemic—and its impact upon a marriage that was already buckling under almost intolerable strain. The story’s surprise turn is that, though the grief-stricken wife succumbs for years to crippling depression and though the husband absconds and disappears into his work, the marriage miraculously survives, recovers, and becomes stronger. The wife and husband in question are Anne Hathaway (or Agnes, as she was named in her father’s will and as O’Farrell calls her) and William Shakespeare.

The novel begins in the provincial market town Stratford-upon-Avon, where the eleven-year-old Hamnet, the Shakespeares’ only son, is alarmed by the sudden eruption of strange symptoms on the body of his twin sister, Judith: “He stares at them. A pair of quail’s eggs, under Judith’s skin. Pale, ovoid, nestled there, as if waiting to hatch. One at her neck, one at her shoulder.” The swollen lymph nodes, or buboes—the dread signs of bubonic plague—seem to have come from nowhere, but in a tour de force of contact-tracing O’Farrell reconstructs the chain of random events and haphazard encounters that could have led the fatal bacterium Yersinia pestis to the Shakespeare house on Henley Street:

The flea that came from the Alexandrian monkey—which has, for the last week or so, been living on a rat, and before that the cook, who died near Aleppo—leaps from the boy [in Murano] to the sleeve of the master glassmaker, whereupon it makes its way up to his left ear, and it bites him there, behind the lobe.

And so it goes, on and on along trade routes by land and by sea, until it reaches Warwickshire in 1596.

To readers living in the shadow of a virus that made its way from a wet market in Hubei province to the nursing home around the corner, the story has a ghastly timeliness, though it is some consolation to note that the bubonic plague that struck Europe repeatedly from the fourteenth century onward was far more lethal than what we have been experiencing, and that, unlike Covid-19, it attacked the young and the old with equal ferocity.

O’Farrell brilliantly conveys the horror and devastation the plague brought to individual households—such as Shakespeare’s, as she imagines it—and to entire communities. There is no evidence of what actually killed Shakespeare’s son in 1596, but plague is a reasonable hypothesis. An outbreak in Stratford in 1564, the year of Shakespeare’s birth, took the lives of around a fifth of the population, and the disease recurred throughout the century with nightmarish frequency.

The surviving records of Shakespeare’s life are scanty; those of his wife still scantier. At the age of eighteen he married a woman eight years older than he, and by the time he reached twenty-one, he had fathered three children. This much is clear. And then he evidently abandoned them, leaving them in Stratford, where he was born, and heading off to the capital to write or to act or to do whatever it was that he imagined he was going to do. True, as the years passed, he returned from London from time to time, presumably to visit his wife; his eldest daughter, Susanna; the twins Judith and Hamnet; and his aging parents. And, as his wealth increased, he sent money back to Stratford, resettled his family in a very large brick-and-timber house, and made a succession of local real estate and commodity investments.

To that extent he remained connected. But it is telling that there were no more children born to Agnes and Will, and there is no evidence that the busy playwright shared his rich inner world with his wife or that he involved himself in the daily lives of his offspring.

Archival records suggest that actors who came from the provinces more typically brought their families to London and settled them there. And if the sonnets have any autobiographical truth to them, his most intense emotional and sexual interests lay outside the bounds of his marriage. Between the family in the house on Henley Street in Stratford and the poet in his rented rooms on Silver Street in London, there seems to have been an almost unbridgeable distance.

Biographers presume that Shakespeare must have rushed home in 1596 when his eleven-year-old son Hamnet fell gravely ill from unknown causes, but even that is by no means certain. The boy died in August and Stratford was a two-day ride from London, so it is possible that when word reached the playwright it was already too late. Had there been any warning signs? Did he get the news by letter? Or did someone speak some such words as are heard in a brief exchange in The Winter’s Tale: “Your son…is gone.” “How, ‘gone’?” “Is dead.”

Advertisement

If these words from a late play are somehow linked to what Shakespeare actually experienced in 1596, they are displaced from autobiography and absorbed into someone else’s story; this is how the terrible news reaches a character named Leontes. There was no general inhibition in this period from writing directly from personal experience; quite the contrary. When an outbreak of bubonic plague took his seven-year-old son Benjamin, Shakespeare’s friend and rival Ben Jonson gave voice in an exquisite twelve-line poem to his bitterly painful leave-taking:

Farewell, thou child of my right hand, and joy;

My sin was too much hope of thee, loved boy.

Seven years thou wert lent to me, and I thee pay,

Exacted by thy fate, on the just day.

O, could I lose all father now! For why

Will man lament the state he should envy?

To have so soon ’scaped world’s and flesh’s rage,

And if no other misery, yet age?

Rest in soft peace, and, asked, say, “Here doth lie

Ben Jonson his best piece of poetry.”

For whose sake henceforth all his vows be such,

As what he loves may never like too much.

It is striking that Shakespeare, as far as we know, left nothing comparable to so direct an expression of parental grief. Though this is the same author who wrote startlingly intimate poems to the young man and the dark lady and, in the words of a contemporary, circulated these “sugared sonnets among his private friends,” Shakespeare seems to have drawn an impenetrable curtain around his feelings, whatever they were, for his family.

In 1616, as he lay dying at the age of fifty-two, Shakespeare signed, in a shaky hand, a will that made many bequests, sentimental and otherwise. To his younger sister Joan he bequeathed £20 “and all my wearing apparrell,” along with the right to live in part of the house on Henley Street—the house in which she and her brother had grown up—for a nominal rent. To John Heminges, Henry Condell, and Richard Burbage, fellow actors and shareholders in the Globe Theater, he bequeathed twenty-six shillings and eightpence each to buy mourning rings, and he gave the same sum to his lifelong friend Hamnet Sadler “to buy him a ringe.” To Thomas Combe, the twenty-seven-year-old relative of a business associate, he left the sword that likely would have gone to his son Hamnet, had he lived.

These provisions—including the sum of £10 to “the poore of Stratford”—are the record of a thoughtful man who has accumulated a great deal of property to dispose of, from the “broad silver gilt” bowl in his grand house to the “barnes, stables, orchardes, gardens, landes, tenementes” that he owned throughout Stratford-upon-Avon and its surrounding villages. He was explicitly concerned to keep Thomas Quiney, the husband of his daughter Judith, from getting his hands on the money she would inherit. And he was equally explicitly concerned to settle most of his substantial estate on his elder daughter, Susanna, married to Dr. John Hall, and on her male heirs.

What is famously notable is the apparent absence of any significant bequest to his wife of thirty-four years. Various explanations have been offered, most plausibly that by custom and perhaps by law she would, as his widow, have been entitled during her lifetime to enjoy a portion of his estate. Still, a glance at comparable wills drawn up by people in Shakespeare’s milieu calls attention to what seems to be missing. From the will of his friend Henry Condell: “I give devise and bequeath all & singuler my freehold Messuages landes Tenementes and hereditamentes whatsoever…unto Elizabeth my welbeloved wife.” From the great actor Richard Burbage: “He the said Richard, did nominate and appoint his welbeloved wife Winifride Burbage, to be his sole Executrix of all his goodes and Chattelles whatsoever.” Likewise the theatrical entrepreneur Philip Henslowe: “I give and bequeath unto Agnes Henslow my loving wife, all and singuler my Landes, Tenementes, hereditamentes and Leases whatsoever.” William Bird, the lead actor in the Earl of Pembroke’s Men: “All other of my goods and chattells whatsoever…I give and bequeath unto my dearly beloved wiefe Marie Bird.” And the actor Thomas Downton, also of Pembroke’s Men: “I do make & Constitvte Iayne my welbeloved & Constant wife my sole Exectatrixe of all my personall Estate.” The list could go on.

The sense of something missing is heightened rather than relieved by a single line evidently inserted, after the document was already drawn up, into Shakespeare’s will: “I gyve unto my wief my second best bed with the furniture.” That’s it. No “loving,” no “dearly beloved,” no “well-beloved and constant,” let alone any hint of the sentiment that led his friend John Heminges to direct that he be buried as near as possible “to my loueinge wife Rebecca.” When Shakespeare contemplated his final resting place, he wanted only to lie undisturbed: “Blessed be the man that spares these stones, And cursed be he that moves my bones.”

Advertisement

Maggie O’Farrell constructs a very different story from the unhappy marriage suggested, to me at least, by these scattered archival traces. To be sure, in her telling, the absent father does not return to Stratford in time to witness the terminal illness of Hamnet. He arrives in time only for the laying out of the corpse and the bleak funeral. Then, to the intense distress of his wife and muttering something inadequate about his theater company, his season, and his preparation, he soon leaves again for London. But that apparent abandonment is folded into what O’Farrell imagines as a story of deep, enduring love.

Though she is in a distinct minority, O’Farrell is not the first to imagine it so. Already in the nineteenth century some biographers suggested that the best bed would have been reserved for visitors and that the second-best bed must have had sentimental value. Hence, in Hamnet, Susanna takes over some of the household tasks from her grieving mother and, at her father’s bidding, buys new furniture for the house, but Agnes “refuses to give up her bed, saying it was the bed she was married in and she will not have another, so the new, grander bed is put in the room for guests.”

As for the absence from the will of terms of endearment, these are mere conventions, and the most eloquent writer the world has ever known would hardly have needed or welcomed recourse to such trite phrases. The deepest emotional bonds may be precisely those that are literally inexpressible. Within his own family O’Farrell’s Shakespeare—who is never referred to in the novel by name but only as “he” or “her husband” or “the father” and the like—is a man of conspicuously few words. Even his courtship of Agnes, as O’Farrell depicts it, is a string of monosyllables and silences: “‘I…’ he begins, without any idea where that sentence will go, what he wants to say. ‘Do you…’”

As O’Farrell acknowledges, her vision of the Shakespeare marriage is indebted to a 2007 book by Germaine Greer, Shakespeare’s Wife. In Greer’s account Agnes Hathaway Shakespeare was an impressive person who has been dismissed, belittled, and slandered by centuries of misogynistic male historians and critics. “The Shakespeare wallahs”—among whom, I regret to say, I prominently figure for Greer—

have succeeded in creating a Bard in their own likeness, that is to say, incapable of relating to women, and have then vilified the one woman who remained true to him all his life, in order to exonerate him.

Speaking for myself, I never thought that Shakespeare was “incapable of relating to women,” only that he seems to have been incapable of relating to his wife. And I have never been inclined to vilify Agnes or to blame her in any way for her husband’s neglect or aversion.

With considerable energy and resourcefulness, Greer combs the surviving records for signs that Agnes was an accomplished and steadfastly loyal wife. Shakespeare scholars have not, so far as I know, embraced her suggestion that Agnes was responsible for the creation of the First Folio or that she may have written a still-undiscovered will leaving money “in trust to be spent on further publishing of her husband’s work,” but O’Farrell, for one, has been inspired by Greer’s effort to imagine a wife more substantial than the one James Joyce described as a “boldfaced Stratford wench who tumbles in a cornfield a lover younger than herself.” And the result is a satisfying and engaging novel that conjures up the life of a strong, vulnerable, lonely, and fiercely independent woman.

O’Farrell does Greer one better by depicting Agnes as what the Renaissance would have called a “wisewoman,” that is, a healer with special powers. Those powers derive for the most part from a deep understanding of the medicinal properties of plants, but there is something uncanny about what she can do. The first time Agnes and Shakespeare meet—at the country farm where the teenage Shakespeare is tutoring her stepbrothers in Latin—Agnes takes his hand and, gripping the flesh between his thumb and forefinger, mysteriously divines his inner nature. She discovers

something she would never have expected to find in the hand of a clean-booted grammar-school boy from town…. It had layers and strata, like a landscape. There were spaces and vacancies, dense patches, underground caves, rises and descents…. She knew there was more of it than she could grasp, that it was bigger than both of them.

It is easy to forgive O’Farrell the shopworn phrase “bigger than both of them” since it gestures toward what must have seemed, to anyone capable of perceiving it, indescribably strange about Shakespeare’s inner landscape.

The magnitude of that landscape, in O’Farrell’s account, is what drew Shakespeare to Agnes but what also drove him to leave her and their three children and the rest of his family, including his parents, and head off on his own to London. As the novel depicts them, Shakespeare’s mother was narrowly conventional and his father, a glover, was a drunken, irascible brute. To escape from them was a necessity. But the budding playwright wanted his beloved Agnes to join him. It was she, in O’Farrell’s reckoning, who always found a reason to delay: “Until spring comes. Until the heat of summer is over. When the winds of autumn are past. When the snow has melted.” Her motive was to preserve the lives of their precious children, to guard them from the hazards of the disease-ridden city. To this end she was willing to subordinate her deep love for her husband. And it is here, in her predominating maternal solicitude, that the novel finds its real life.

For disease and death haunted not only the crowded cities of Tudor England but also its country towns and leafy rural settlements. Given the general state of Renaissance medical knowledge, a sick person stood a better chance with the plant-based cures of a wisewoman such as O’Farrell’s Agnes than with the hideous cuppings and purges of the best Padua-trained physician. Little Hamnet, frightened by the sudden illness of his twin sister, is right to be desperately seeking his mother. But she is out in the fields, more than a mile away, collecting herbs for her healing practice. By the time she returns home, the symptoms on the little girl’s body of bubonic plague are unmistakable, and with every passing moment they are getting worse.

Narrating severe illness is for O’Farrell a personal specialty. In her 2017 memoir I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death, she describes a childhood illness that left her bedridden for a year and from which she was not expected to recover, and, still more harrowing, she depicts in excruciating, searing detail her infant daughter’s immune-system disorder:

Her skin is bubbling and blistering, each breath a struggling symphony of whistles and wheezes. Her face, under the scarlet hives, under the grotesque swelling, is ghastly white.

I think: she cannot die, not now, not here. I think: how could I have let this happen?

O’Farrell brings this direct personal experience to bear as she imagines all of Agnes’s frantic efforts to save her daughter and her irrational but unbearable feelings of responsibility. Ultimately, as we know, it was not Judith who died but her twin brother. (Judith in historical fact lived to the age of seventy-seven, dying in 1662.) Here the novel has recourse to the occult forces that had earlier accounted for Agnes’s prescient reading of her young suitor’s hand. Hamnet silently and mysteriously wills himself to take his sister’s place in the clutches of death, leaving Judith to recover as if her mother’s herbal remedies had saved her.

The recovery only intensifies Agnes’s tormenting guilt, for she feels that she somehow failed to focus her attention adequately upon the boy, and she plunges into a grief that is not unmixed with anger at her husband for not being there when she most needed him. Her anger intensifies when, having laid his son in the ground, Shakespeare announces his intention to return to London. But even in the midst of her anger, Agnes, as O’Farrell suggests, must have understood what was impelling him to leave. “You are caught by that place, like a hooked fish,” she tells him:

“What place? You mean London?”

“No, the place in your head. I saw it once, a long time ago, a whole country in there, a landscape. You have gone to that place and it is now more real to you than anywhere else. Nothing can keep you from it. Not even the death of your own child.”

After her husband leaves, Agnes succumbs to what we would now call clinical depression. And lest we think that such depression is a novelist’s historical anachronism—that parents in the early modern period must have been hardened to the death of children, since it was so terribly common—we might consider the diary of Richard Napier, a seventeenth-century Buckinghamshire astrological physician. The historian Michael MacDonald, who deciphered Napier’s voluminous notes and analyzed them in a remarkable 1981 book called Mystical Bedlam: Madness, Anxiety, and Healing in Seventeenth-Century England, found that the physician treated numerous parents, and especially mothers, who were “ever leaden with grief” after a child’s death. As William Paulet, the Marquis of Winchester, had written in 1586, “The love of the mother is so strong, though the child be dead and laid in the grave, yet always she hath him quick in her heart.”

Such is the burden, brilliantly depicted, of O’Farrell’s Agnes. Her depression lasts for years, and, though it feels as if it could never get worse, it is intensified when she learns, to her horror, that her husband has written a play that bears her son’s name. (The names Hamnet and Hamlet in this period were interchangeable.) How, she asks herself, could he have been so callous as to exploit for mass entertainment his family’s intimate tragedy?

In the novel’s climactic scene, Agnes travels to London to confront her husband. There, in the midst of the general urban filth and confusion, she has two revelations. Her first comes when she rushes to his rooms. She does not find him there, but, crucially, she finds no sign that anyone besides the playwright has been there. This is the room of a solitary writer—no trace of a lover, male or female. On his desk there is a letter to her that he has begun but left unfinished. The second and still greater revelation comes when she pays her penny, thrusts herself amid the heaving crowd, and enters the wooden O of the Globe. There on the raised stage she sees her husband, his face made up in ghastly white, playing the part of a ghost, the ghost, as the characters around him say and the crowd repeats, of Hamlet:

To hear that name, out of the mouths of people she has never known and will never know, and used for an old dead king: Agnes cannot understand this. Why would her husband have done it?

Thoroughly disgusted, she is readying herself to leave when she is transfixed by the appearance on stage of another character, a boy, or rather a young man, with the precise mannerisms of the dead Hamnet—“walking with her son’s gait, talking in her son’s voice”—and at just the age he would have been, had he lived. For a moment she is utterly baffled, and then the meaning of it all comes over her: “Hamlet, here, on this stage, is two people, the young man, alive, and the father, dead. He is both alive and dead. Her husband has brought him back to life, in the only way he can.”

To perform this extraordinary feat, she suddenly understands, her husband, in taking on the role of the ghost, has taken his child’s death and made it his own: “He has put himself in death’s clutches, resurrecting the boy in his place.” The reader of the novel also knows, as Agnes cannot, that in offering himself in place of the other, Shakespeare has in effect done for his son what his son did for his gravely ill sister. What Agnes can and does know is that through the power of art her husband has redeemed himself and saved whatever he could of his lost son.

Did it actually happen this way? Almost certainly not. Was the moribund marriage saved? I doubt it. But I too am convinced that Shakespeare drew upon his grief and mourning to write the astonishing, transformative play that bears his son’s name. With her touching fiction O’Farrell has not only painted a vivid portrait of the shadowy Agnes Hathaway Shakespeare but also found a way to suggest that Hamnet was William Shakespeare’s best piece of poetry.