Here are some ideas for a social revolution. All schools shall be coeducational, with no fees, plenty of outdoor exercise for pupils, and emphasis placed on both learning a foreign language and treating animals with kindness (in order to reduce in children any disposition toward violent behavior). There shall be equality of partners in cohabiting relationships and equal division of legacies among family heirs. No special favors granted to firstborn sons. Every woman shall aspire to earn her own living (“the true definition of independence”) rather than employing sexual guile and physical appearance to attract a wealthy lover or spouse. Nothing here sounds especially revolutionary (with the possible exception of a petting menagerie). Nothing, that is, until we realize that these suggestions were proposed by an unmarried woman in the final decades of the eighteenth century.

The woman who advocated such an enlightened society was Mary Wollstonecraft, known to the world today primarily—and misleadingly, in the view of Sylvana Tomaselli—as the author of Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792). Tomaselli, a respected Wollstonecraft scholar, seeks to persuade us in Wollstonecraft: Philosophy, Passion, and Politics that her subject’s thinking and personality can be better divined in her other published works. These include the wonderfully fiery Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796), the latter composed of twenty–five letters to her faithless common–law husband, Gilbert Imlay, and published the year before her death. Less helpful to our understanding of an extraordinary woman, Tomaselli argues, is the much–quoted and often lachrymose correspondence between Wollstonecraft and her sisters, which provided a place for her to air private moments of frustration and despair.

Few, if any, mother–daughter pairs compare to the glowing diptych presented by Wollstonecraft and her second daughter, Mary Godwin, better known by her husband Percy’s surname as Mary Shelley. Wollstonecraft, who died in the late summer of 1797 at the age of thirty–eight, just eleven days after giving birth to Mary, offered her dazzled and often enraged contemporaries a vision of liberated womanhood that would help to make her the darling of twentieth–century feminists. Her bold and studious daughter would go on to write Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus at the age of nineteen and to provide, in the Creature that Victor Frankenstein brings to life in his laboratory, what the critic Frances Wilson has aptly described as “the world’s most rewarding metaphor.”

Scholars who see links between Victor Frankenstein’s artificially manufactured progeny and mankind’s persistent attempts at human engineering have bestowed on Mary Shelley the dubious title of wicked stepmother to the science of genetics. Addressing Shelley’s novel and the ethics of current artificial intelligence technology, Eileen Hunt Botting poses provocative questions in Artificial Life After “Frankenstein” about the rights of the man–made robots that now can match humanity in many things but not—so far—consciousness. How, Botting encourages us to ponder, might Wollstonecraft have legislated for the rights of the Creature born to her brilliant daughter—so Shelley would claim in the 1831 preface to her novel—in a state of wakeful reverie? (“I saw the hideous phantasm of a man…show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half–vital motion.”)

And what, the reader of these two books may wonder, might that remarkable mother and daughter have thought about our present pandemic, one against which the plague–stricken and swiftly depopulated world of Shelley’s remarkable novel The Last Man (1826) would have had no redress? Her inspiration was the cholera epidemic that began in Asia in 1817 and spread over the next seven years to Africa and the Middle East, devastating societies that possessed no understanding of a water–borne disease.

Fortitude is a quality that Tomaselli brings to the fore in her study of Mary Wollstonecraft, sensitively created from an informed overview of her subject’s writings. It was a quality for which Wollstonecraft had immense respect, and it proved essential to her own survival. Born in 1759 to a grievously mismatched couple, the enterprising, passionate Wollstonecraft was saddled by her ineffectual parents with two younger sisters to look after. She smarted at the comfortable and secure existence that was deemed to be the right of her tough older brother, Ned, an attorney, who felt no need to assist his impoverished female siblings when their widowed and bankrupt father abandoned them to live with his second son, Charles, at Laugharne, a farm in Wales. (Revealingly, after encouraging her unhappy sister Elizabeth to leave a brutal husband, Wollstonecraft defended herself by saying that such a tyrant as her brother–in–law would have caused even a bully like Ned to “flinch.”)

It was left to Mary—after rescuing Elizabeth from her husband—somehow to raise money to support them. She did it by setting up and running a school in Newington Green, that thrilling London hotbed of well–read radical dissenters led by Richard Price (his admirers included Thomas Paine, David Hume, Thomas Jefferson, and Adam Smith), with the help of her sisters and an adored friend, Fanny Blood. In 1785 she traveled to Portugal to assist the recently married Fanny, after whom she would later name her own first child, through the last stages of pregnancy. Fanny died shortly after giving birth, and Wollstonecraft, acting with characteristic generosity, devoted the handsome advance of £10 (about £1,500 today) for her first and courageously outspoken book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787), to establishing a new life in Ireland for her friend’s destitute parents.

Advertisement

The school, having lost most of its revenue–earning boarders during Mary’s absence abroad, and despite all her efforts to keep it going on borrowed money, was forced to close. Having honorably discharged her debts, and acting against the inclination of her proudly independent spirit, Wollstonecraft took a job as a governess to the children of Lord and Lady Kingsborough in County Cork.

It’s surprising that no writer has yet published any novel of note based on Wollstonecraft’s unhappy year in Ireland. Her young pupils adored her; a married friend of the Kingsboroughs fell swiftly under her spell. Her Anglo–Irish employers showed kind intentions, presenting their governess with a volume of Shakespeare and tickets to a two–day Handel celebration. Tomaselli makes a persuasive case that music, even more than the plays of Shakespeare, became a source of lifelong delight for her. While railing against the pomp and leisured circumstances of a pampered world, Mary never forgot the sensation of having been “raised from the very depth of sorrow, by the sublime harmony of…Handel’s compositions.”

But the spectacle of a careless mother lolling among her lapdogs while ignoring her children (the amiably indolent Lady Bertram in Mansfield Park owes much to Jane Austen’s reading of Wollstonecraft’s writings) provoked her fierce indignation, as did any rash attempt by Lady Kingsborough to flaunt her superior status. There’s never been much doubt that it was at the Kingsboroughs’ elegant house that Wollstonecraft’s enduring detestation of social hierarchies was born.

Armed with a first novel called Mary—it celebrated the life of a strong–willed, self–taught, unconventional woman not unlike its author—Wollstonecraft returned to London in 1787 to work as a commentator, editorial assistant, and freelance translator for Joseph Johnson, a bookseller and the publisher of the well–regarded Analytical Review. The first woman to earn a steady living by her pen—Johnson paid her a monthly retainer—she became one of the best–informed (as well as one of the most opinionated) journalists of her outspoken times. Her trenchant views on a remarkable range of subjects provide Tomaselli with rich pickings, among them Wollstonecraft’s 1790 appreciation of Charles Burney’s four-volume history of music, in which she paid tribute to “this captivating art…the food of devotion.”

Writers on Wollstonecraft have, until very recently, overemphasized her love of reason; Tomaselli does her subject a great service in quietly stressing Wollstonecraft’s persistent wish to be moved not only by what she heard, but by what—as a keen walker and lover of nature—she observed. “My darling Westwood” was how she addressed one of her favorite rambling grounds, while her last essay was titled “On Poetry, and Our Relish for the Beauties of Nature.” She was, in short, a Romantic.

Twenty–five years ago, Tomaselli edited a joint edition of Wollstonecraft’s two volumes of “vindications.” Here, she gives the earlier and far less familiar of them its proper due. Published anonymously in 1790, A Vindication of the Rights of Men was Wollstonecraft’s deliberately “manly” response to Edmund Burke’s extravagantly rhetorical defense, in his Reflections on the Revolution in France, of Marie Antoinette and an entire world of tradition–enshrined aristocracy, which he took that doomed queen to epitomize. Written at white–hot speed to reach readers in the same month as Burke’s book, every page of the Vindication was illuminated by Wollstonecraft’s vigor, wit, and spirit. The injustices of slavery, of primogeniture, of great estates, of titles (“the corner–stone of despotism”), of Burke’s notion that “littleness and weakness” (in a woman, naturally) “are the very essence of beauty”: all were targets for her caustic shafts in the first and most arresting of the volley of denunciations (if not the best known; that honor belongs to Paine’s The Rights of Man) to be hurled at Burke’s exaltation of an exquisitely moribund society.

Anger, impetuousness, passion—none of these characteristics made Wollstonecraft a likely wife for William Godwin, the coldly clever political philosopher whom she met in 1791 at a dinner party held by Johnson to honor Paine. Five years later, Godwin reluctantly married her (he opposed the institution of marriage even more vehemently than she did) solely in order to legitimize their unborn child, whom both of them fondly anticipated would be a son—a second William.

Advertisement

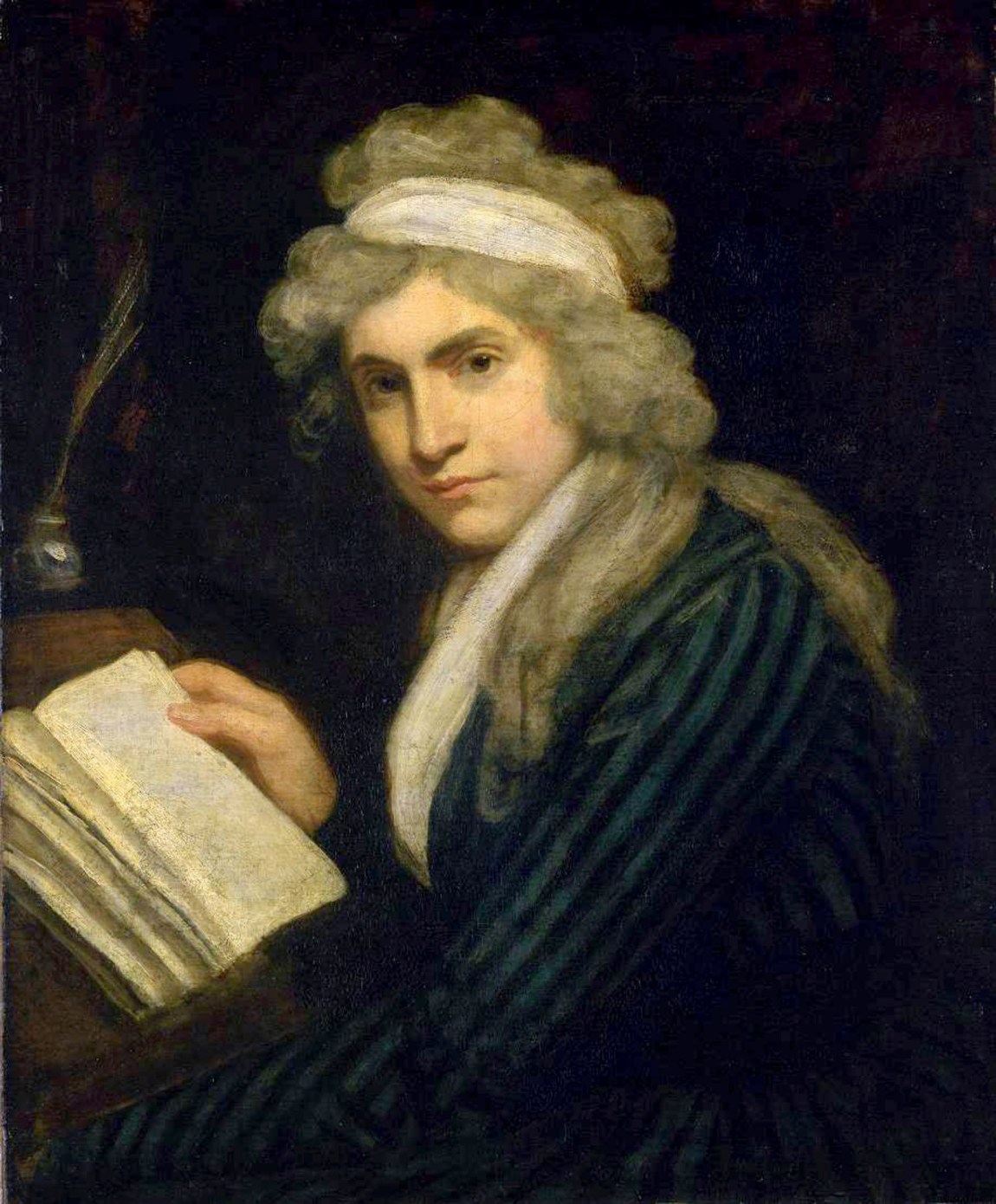

Wollstonecraft’s previous relationship with Gilbert Imlay had been, in Tomaselli’s empathetic words, one of “utter, indeed terrible devotion…and physical need,” which culminated in two attempts to take her own life. With Godwin, by contrast, she at last achieved the honest and equal partnership to which she fervently believed every good marriage should aspire. Tomaselli, while reminding us of her emotional engagement with all the arts, wonders whether it was Wollstonecraft, rather than her husband, who invited their friend the artist John Opie to portray her, happy and expectant, during the last summer of her tragically short life. If so, she chose well: the flushed cheeks and glowing eyes of Opie’s portrait testify to the contentment of a union that Virginia Woolf described more than a century later as the most fruitful of all Wollstonecraft’s bold social experiments.

Mary Godwin never knew her mother, but she grew up with the Opie portrait watching over her in a household that, venerating Wollstonecraft, sought always to follow the tenets of her books. Fanny Imlay (Wollstonecraft’s daughter by Gilbert Imlay) and Claire Clairmont (Mary’s spirited stepsister) were as ardent in their admiration of Wollstonecraft as Mary was. So was Percy Bysshe Shelley. The hotblooded, barely postadolescent author of one long self–published poem, Queen Mab, met Miss Godwin at her father’s house and courted her beside her mother’s grave (with an admiring Miss Clairmont acting as their chaperone). When Shelley left his wife in 1814 to run off to the Continent with Mary and her stepsister, copies of Wollstonecraft’s books accompanied them; the young trio naively supposed that the trip would gratify Mary’s father, a twice married and greatly subdued political firebrand who no longer regarded matrimony as “the most odious of monopolies.”

Godwin’s chilling response was to banish his daughter forever from his house. (She was only—and grumpily—allowed back after marrying the recently widowed Shelley in December 1816.) Those looking for biographical sources of the anguish of the Creature whom Victor Frankenstein impetuously rejects (“Unable to endure the aspect of the being I had created, I rushed out of the room”) might do worse than to consider the unhappiness of the book’s sensitive author, a daughter who remained dutifully attentive until the end of a sour old man’s increasingly shrunken life (Godwin died at the age of eighty in 1836).

David Wootton, the editor of a splendid new edition of Frankenstein that includes a rich variety of relevant texts, prefers to focus on the contribution made to the novel by Mary’s reading of contemporary articles on travel (the book’s first narrator, Robert Walton, is bound for the North Pole, which he describes as “the favourite dream of my early years”). Wootton’s magisterial introduction grants equal significance to the earnest discussions about generating life that took place in 1816 at Lord Byron’s lakeside villa in Switzerland, where Frankenstein was conceived. Wootton’s readers might wish he had looked more closely at Mary Shelley’s past for the novel’s origins. She had been an imaginative and impressionable fifteen–year–old girl when she spent a year away from home in Dundee, a Scottish whaling port from which ships regularly voyaged toward the North Pole. It was there, as she revealed in the 1831 preface to her reissued novel, that “my true compositions, the airy flights of my imagination, were born and fostered.”

While Wootton leads us back to the sources of Frankenstein, Botting alerts readers of Artificial Life After “Frankenstein” to the novel’s lessons for an age in which robots—the insensate descendants of Victor Frankenstein’s painstakingly assembled Creature—occupy an increasingly significant social position.

Previously, in Mary Shelley and the Rights of the Child (2017), Botting plausibly interpreted Frankenstein as Shelley’s examination of the fate of a stateless orphan deprived of every child’s right: a place within the community and the love of a parent or benign surrogate. There—and in Artificial Life—Botting stresses the Creature’s importance as an ill–treated representative of Wollstonecraft’s belief in the right of every sentient being to affection; it was a view of universal benevolence that Mary Shelley shared. Frankenstein, in Botting’s view, is Shelley’s own vindication, a literary one that speaks for “the right of all creatures—no matter the circumstances under which they are made—to share ‘love of another’ and companionship with other ‘sensitive’ beings.”

The plot of Frankenstein—the battle between Creator and Creature that reaches its dramatic conclusion in the frozen wastes where Captain Walton’s ship lies locked in ice—has passed from fiction into myth. (The brief and beautifully constructed novel retains much of its original power to shock and provoke.) Shelley’s narrative of mutually inflicted suffering offers Botting an opportunity to present the book as a vindication that precedes Alan Turing in arguing that we should treat what we create with the same kindness that loving parents would bestow upon their own child.

Along the way to the vexed question at the heart of her book—do machines built and programmed by humans merit a benevolence they can appear to simulate but not feel?—Botting ushers us into the gruesome wonderworld of Frankenstein’s fictional heirs. Pride of place in this unlovely assembly goes to a couple of Victorian writers, Robert Louis Stevenson and H.G. Wells. Stevenson, the creator of Dr. Jekyll and his conscience–free alter ego, Mr. Hyde, was a close friend of Shelley’s son Percy Florence Shelley at the time he wrote his terrifying study of the doppelgänger.

That troubling theme of the double closely connects Stevenson both to Mary Shelley’s skillful entwining of the pursued with the pursuer and to her father’s influential novel, Things as They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams (1794). However, Wells, another of Frankenstein’s heirs, seems more pertinent today. The Island of Doctor Moreau, published in 1896, describes a mad scientist’s attempt to blur the line between the human and the nonhuman, the humane and the inhumane, by creating—from the vivisected bodies of animals—“Beast Men.” The way in which the unfortunate creatures are assembled from random parts appears to be borrowed directly from Frankenstein. Lacking the intelligence and eloquence of Shelley’s magnificently articulate “fiend,” Moreau’s Beast Men are spared the emotional torment of rejection and social isolation to which Victor Frankenstein’s superhuman giant child was condemned by his creator.

In Philip K. Dick’s prophetic novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), one of his characters poses the question: “Do you think androids have souls?” In this novel a dying female android identifies the potential for empathy as being what divides humans from androids (also called “replicants”), her own life having merely “consisted of imitating the human.” Dick’s book forms part of Botting’s brief but excellent survey of the literary and film history of replicants, an entertaining résumé that smoothly leads us toward the most unsettling aspect of her argument for universal compassion.

Empathetic androids remain, at present, theoretical; credible though the androids seem in films like Blade Runner (1982), Ridley Scott’s adaptation of Dick’s novel, or Spike Jonze’s Her (2013), they have no real–world equivalent. The fact that a machine’s algorithm has consistently defeated a human grandmaster of Go (a game that allegedly offers as many configurations of moves as there are atoms in the universe) has not persuaded its crestfallen opponents that it exhibits artificial general intelligence—the power to understand and think like a human being—which seems to remain (should we lament the fact?) in the future.

But if the robots for whose rights Botting seeks to make an ethical case are insensate—no evidence yet suggests that they feel pleasure when they triumph at Go—why should their rights be of concern? There’s a point in her book where she seems ready to invert the argument. Describing a 2016 London conference that was catchily titled “Love and Sex with Robots,” Botting presents the contentious case made by the conference’s cochair Kate Devlin for the use of androids in residential care homes for the purpose of companionship, or even sex. Not such a terrible idea, a few might quip, during the isolation imposed by a pandemic, but then must we also—as Botting pulls back a bit to suggest—grant these obliging machines the right to be treated with kindness by their owners? Consider the world satirized in Jeanette Winterson’s 2019 novel Frankisstein, in which the charismatically odious Ron Lord (a riff on Lord Byron) manufactures robots as sex slaves. What might it do to human consumers to exploit machines in this way? Could an ethical case be made, as Devlin has posited, for providing synthetic children to satisfy the predilections of convicted pedophiles?

Such bold speculation, in Botting’s view, takes us back once again to the original teachings of Wollstonecraft, which her daughter absorbed and poignantly articulated in her greatest novel. While Botting is by no means the first to interpret Frankenstein as primarily a fable about bad parenting, she deepens our sense of the warning it offers. Against the mindless drive for technological progress, Botting attempts to sum up the most important moral lesson that Shelley learned from her mother’s work: “The value of taking a generous and fearless attitude of love toward the whole world.”

And where, precisely, did Shelley first encounter the lesson that she took so to heart? Botting doesn’t specify, but it’s hard to overlook that one of the books Mary carried off from London on her 1814 trip to Europe, two years before she began writing Frankenstein, was her mother’s last novel, Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman. In it Jemima, an attendant working in the asylum where Maria has been unjustly imprisoned, unfolds the story of the cruelties to which she had been subjected by a vicious stepmother. As lonely and rejected by the world as the Creature (“an egg dropped on the sand; a pauper by nature, hunted from family to family, who belonged to nobody”), Jemima attributes the greater part of her misery to a single factor: the absence of parental love.

Reading those words in a book written by the mother she had never known, during the time when her disapproving father had exiled her from his house, how could Shelley not identify with Jemima’s despair and project it onto her own outcast and artificially manufactured creature? If consciousness ushers in suffering, it may well be that the next cyber revolution will prove one of emergent moral choice, and—as Botting’s absorbing book leads us to appreciate—of ethical responsibility both to and by the increasingly sophisticated machines that humankind has begun to create.

This Issue

February 25, 2021

The Trump Inheritance

The Stench of American Neglect

Bildungsonline