Before he ascended into the heaven of Mar-a-Lago, Donald Trump promised, “We will be back in some form.” Perhaps, in a final flourish of one-upmanship, he was stealing the catchphrase of his reviled successor as host of Celebrity Apprentice, Arnold Schwarzenegger: I’ll be back. In The Terminator, Schwarzenegger fulfills his promise by smashing his car through the door of a police station and massacring all the cops. But that odd appendage, “in some form,” suggests a different genre. It belongs at the end of a shlock horror movie, when the supernatural ghoul, vanquished for now by the forces of light, sets up the expectation of a sequel. Trump presented himself as a shapeshifter, a man of many and mysterious forms. In doing so, he brought to mind another kind of movie—not the as-yet-unwritten sequel, but the prequel that bombed at the box office.

In this movie, it is January 2005 and Oprah Winfrey is being sworn in as the first African-American and first female president of the United States. Beaming proudly on the platform behind her is the man she has spent the previous four years serving as vice-president, Donald Trump. The Trump-Winfrey ticket, representing the Reform Party founded by Ross Perot, had narrowly beaten George W. Bush and Al Gore in a tight race in November 2000. Trump had honored his pledge that “I would enter office on the understanding that four years hence I would be back in New York doing the job I love.”

When Trump had announced Winfrey as his running mate, he had pointed out that “the political elites” failed to “understand how many Americans respect and admire Oprah for her intelligence and caring.” Especially after the attacks of September 11, 2001, when she brought comfort and reassurance to a traumatized country, those qualities had shone through so brightly that she won handsomely in November 2004. Donald Trump had opened the way to a new American future in which a Black woman from the Old South embodied a nation that had transcended civil war, the legacy of slavery, racism, misogyny, and the divisions of tribal politics.

This scenario is just a tad counterfactual, but it is not pure invention. At the beginning of this century, Trump was testing the market for a run at the presidency. This was the product he thought Americans would buy: Oprah on his ticket, a guarantee to serve one term only, and an insistence that “one of our next president’s most important goals must be to induce a greater tolerance for diversity.” In his manifesto The America We Deserve (2000), Trump claimed that his friendships with the rapper Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs and baseball outfielder Sammy Sosa had left him with “little appetite for those who hate or preach intolerance.” The horrible murder in Wyoming of a young gay man, Matthew Shepard, had convinced him of the need to “work towards an America where these kinds of hate crimes are unthinkable.” He would, as president, seek to free businesses of tax and regulation, but equally to lift from citizens the burdens of “racism, discrimination against women, or discrimination against people based on sexual orientation.”

This beta version of Trumpism would have sought to create a centrist consensus by uniting conservative economics to liberal social policies (including “a woman’s right to choose”). His fantasy cabinet would have included, for example, both his friend Rudy Giuliani and the “smart and resilient” outgoing first lady, Hillary Clinton (“She was very nice to my sons, Donny and Eric, when she visited New York”). Most strikingly, Trump’s analysis in 2000 was that his putative rival for the Reform Party nomination, a right-wing populist, could never be elected because he had spent too long as a professional loudmouth: “Simply put, Pat Buchanan has written too many inflammatory, outrageous, and controversial things to ever be elected president.”

This kindly, tolerant, politically correct President Trump is like Google Glass, the DeLorean sports car, Sony Betamax, New Coke, or, indeed, Trump Steaks—a product that never found a market. Trump soon realized that it wouldn’t fly. He dropped it and eventually worked his way toward the presentation of a very different commodity. He realized that overindulgence in the “inflammatory, outrageous and controversial” was not an obstacle but a springboard to the presidency.

The phantom Trump presidency of twenty years ago is worth recalling in part as a reminder, at a time when the United States seems to be at a crossroads, that there are few inevitabilities in history. But it also raises a fundamental and urgent question about the nature of the polity that Joe Biden has now inherited. Who created Trumpism? If the answer is simply that Donald Trump did, then one could imagine it as a transient phenomenon, like the coronavirus in his predictions a year ago: “One day—it’s like a miracle—it will disappear.”

Advertisement

As Biden claimed in his inaugural address, “democracy has prevailed” against its enemies. But what if Trumpism was always there, waiting merely to be named? The complete failure of Trump’s first test-run at the presidency suggests that his was a product shaped by the market. The demand existed—Trump had to work hard to come up with the right supply. Nobody much bought Trumpism in its original package. Tens of millions of voters were, and remain, completely sold on the radically reformulated offering. Trump didn’t create his people; his people created Trump.

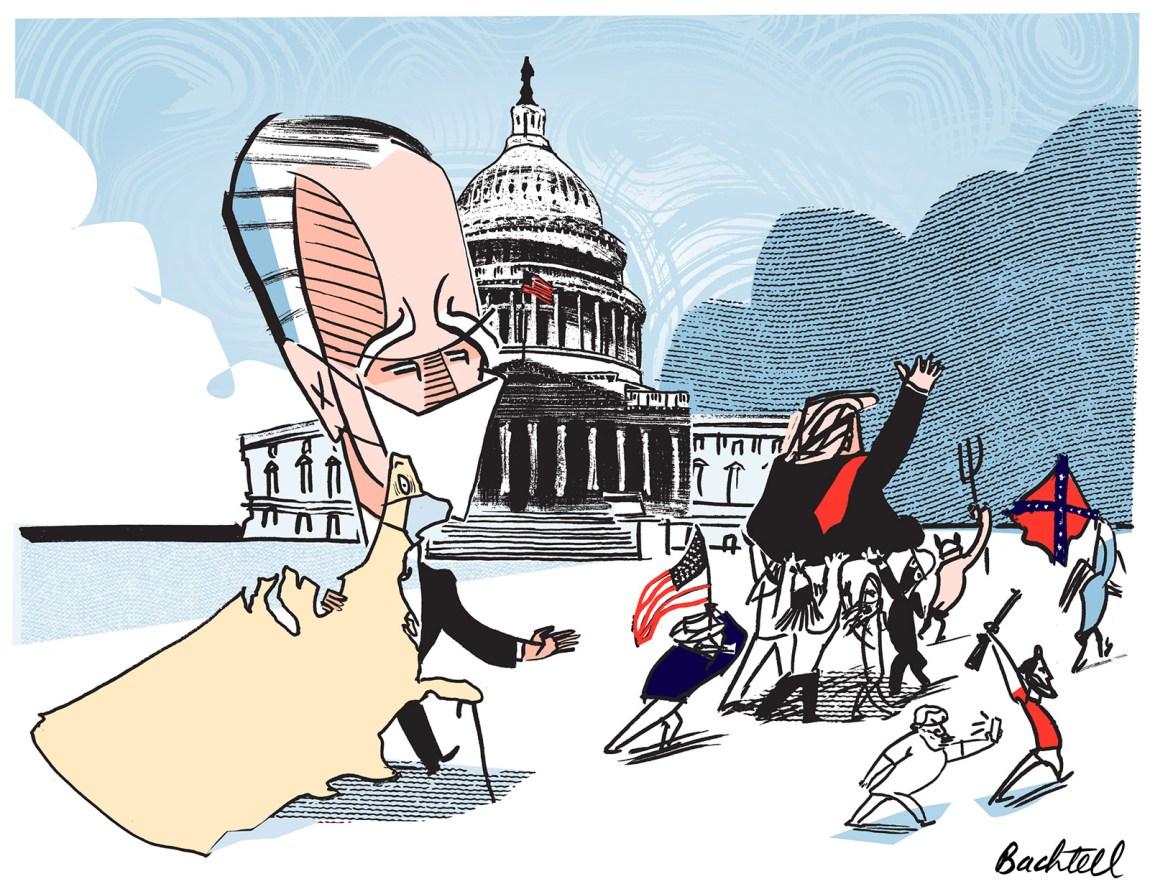

We can frame this question more concretely if we think about the events of January 6, when the vanguard of that people stormed the Capitol in Washington: Did Trump summon the mob or did the mob summon up Trump? This is the nub of the indictment on which Trump was impeached, for the second time, by the House of Representatives and must now be tried by the Senate: How much agency had the mob? Were its “violent, deadly, destructive, and seditious acts,” as the indictment has it, a direct manifestation of the leader’s will? Was there a simple working-through of cause and effect?

Notably, the indictment does not quite say so. It alleges that Trump “willfully made statements” in his address to the rally outside the White House that morning that “encouraged—and foreseeably resulted in—lawless action at the Capitol.” This is a fair description of what happened, and it does not fully amount to a claim that the crowd was obeying anything as clear as an instruction from its leader. The clamorous soundtrack of that day was antiphonal. It was call-and-response. Both Trump and his fans were finding their way by echolocation, signals sent out in one form and returned in another. This is possible only when the relationship between the leader and the led is cooperative and mutual.

Watching those events unfold, I thought of the fourth act of Hamlet, when the mob bursts through the doors of Elsinore:

They cry, “Choose we! Laertes shall be king!”

Caps, hands, and tongues applaud it to the clouds:

“Laertes shall be king, Laertes king!”

Choose we—we get to decide who will be king. These are not mere followers; they see themselves as kingmakers. So did the Capitol invaders: Choose we! Trump shall be president! This is not a docile flock or a robotically mindless mass. It is a crowd that is both making a choice and defining the nature of political choice itself. It is to be decision not by election but by assertion, made not by the mere numerical majority but by “we,” the patriots, the real Americans. Trump was at once the symbol of this power to choose and the vehicle for its enforcement.

This is what old-style conservatives, recoiling from the reality of January 6, managed to evade. Bret Stephens, in a passionate and eloquent op-ed in The New York Times, wrote of “this Visigothic sacking of the Capitol,” and later of “the barbarians…inside the gate” and “the Capitol Hill barbarians.” But as Mark Danner reported in these pages, the invaders thought of themselves as the true Romans, even as the legionaries of Julius Caesar. He saw “women wearing red, white, and blue sweatshirts and draped in red ‘Make America Great Again’ flags like Roman togas.” He spoke to a guy whose homemade flag read “Lead Us Across the Rubicon!”1 Alec MacGillis of ProPublica spotted, inside the Capitol, a “man dressed as a Roman centurion, complete with sandals.” In their own eyes, they were the senators and the legionaries. They were not the wild outlanders from the fringes of empire. They were the empire. The city, they believed, belonged to them—it is they who decide who gets to be hailed as imperator. “Hail Emperor Trump,” the Proud Boys wrote on their private Telegram messages. They came not to bury their American Caesar, but to praise and crown him again.

It nonetheless suits what remains of the former Republican Party to think of themselves as Ciceronian senators and Trump’s mob as vile Visigoths. The imagery of rampaging savages desecrating the neo-Roman Capitol is, in that sense, as reassuring as it is shocking. But it raises the question asked at the end of C.P. Cavafy’s great poem “Waiting for the Barbarians” (in Edmund Keeley’s translation):

Now what’s going to happen to us without barbarians?

Those people were a kind of solution.

They were indeed. The problem they kind of solved was the basic contradiction of the conservatism that came into the ascendant with Ronald Reagan: How do you, on the one hand, denigrate government and, on the other, insist that you are best placed to run it? A large part of the answer always lay in social conservatism, in the maintenance of the power of the state to regulate private behavior and, in particular, to control what women did with their bodies. Another part lay in violence, turned inward against Black communities and out toward foreign enemies. Government could be validated in “law and order” and in war, even as it was being degraded in economics and in welfare.

Advertisement

These solutions have become steadily more difficult. Religious-based social conservatism has a huge popular base, but it cannot sustain the illusion that it is a democratic majority. (Gallup polling suggests that the proportion of voters who accept the gold-standard proposition of the religious right, that abortion should be illegal in all circumstances, is now, at 20 percent, broadly the same as it was in 1975.) Violence against Black communities has become more visible with the ubiquity of cameras and recording devices, and therefore more contested within the political and media mainstream. And the appeal of war has drained into the sands of Iraq and the dust of Afghanistan.

The Tea Party movement of 2009 and 2010 was a trial run for a different kind of solution—the paradox of an insurrectionary conservatism that turned violent hatred of government into a governmental agenda. The movement’s name, after all, evoked at once a riotous revolt against governmental authority and the mythic foundational act of the American state. Its initial demands were those of classic, respectable small-government conservatism: stop President Obama’s health care law; cut the national debt, and prevent the government from interfering in the private economy by rescuing the car industry and protecting some mortgage holders from default.

But you don’t have to dig very far in the archives to find pictures of white men with guns turning up outside Obama’s public meetings on his health care plan. They carried everything from handguns to AR-15 assault rifles and toted signs that called for violent uprising: “It Is Time to Water the Tree of Liberty,” a reference to Thomas Jefferson’s assertion that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” (The Oklahoma bomber Timothy McVeigh was wearing a T-shirt imprinted with the slogan when he was arrested.) A demonstrator at a rally in Maryland hanged a member of Congress in effigy. Sarah Palin, who had been the Republican vice-presidential candidate, used the refrain “Don’t retreat, reload!,” not just at Tea Party rallies but, to hollers of approval, at the Southern Republican Leadership Conference in April 2010. She denied that this was a call to violence, but even she was hardly stupid enough not to know how it sounded to much of her intended audience.

The great gamble of the Republican Party was that this coalition of respectability and riot could hold together, that the rage could be absorbed, exploited, and institutionalized. The GOP became a political lap-dance club: the lust for insurrection would be incited but not consummated. Implicit in this deal was a belief that the party and its professional politicians could still control entry into the arena of legitimate politics. Trump destroyed that smug self-assurance—though it might be more accurate to say that the antigovernment crowd used Trump to destroy the illusion on its behalf.

It is worth recalling that “mob” is, in its original usage, simply an abbreviation of “mobile.” The great crowd that chose Trump as its king is a restless and dynamic force. In the Tea Party years, it latched onto the rather unlikely cause of fiscal conservatism and the rights of billionaires. But ultimately it didn’t really care about balanced budgets, and perhaps not very much about health care—issues that evaporated midway through Trump’s presidency without any loss of enthusiasm among his supporters. It also turned out not to care all that much about the actual building of Trump’s wall or “draining the swamp.” Trump could fail to do the first and make a mockery of the second by flagrant corruption and self-dealing without diminishing the zeal of his fanbase. This is because the mob’s core demand is more fundamental. It wants the power to say who is real and who is not.

The phrase that echoed throughout the invasion of the Capitol was “This is our house.” It is a double claim of belonging—both “we belong here” and “this belongs to us.” It is an assertion of title. This is what Trump came to understand—that the market he was seeking lay above all in the sense of unequal entitlement. His original political project failed because it rested on a vague notion of the universality of the American Dream. His initial appeal was to the promise of American capitalism—that everyone could be a winner. Winning was about what you do, not who you are. Anyone, rich or poor, Black or white, who worked hard enough and had enough talent could triumph—just look at Oprah. A Trump presidency would be a cross-racial coalition of winners.

In the drastic makeover of his merchandise, Trump retained some of this rhetoric, but it now merely glossed over a much more visceral allure. Success is no longer primarily about what you do. Success depends on a racial and national patrimony—a specifically American entitlement. It was not accidental that Trump’s passage from the failed product launch of 2000 to the spectacular success of 2016 was precisely through this idea of birthright: his racist campaign to suggest that Obama was not entitled to be president because he was born in the wrong place. Birtherism—which Trump tried to revive against Kamala Harris after she joined Biden’s ticket—was the gateway to a politics of collective privilege. It unlocked the central concept of the rebranded Trumpism: real Americans. This idea is potent because it creates an expansive elite, a popular prerogative that can contest political power on more or less equal terms with the hated liberal concept of universal rights.

Once he understood that his market was in that idea, Trump brought together two versions of the claim to innate superiority. One is national: America First. The United States has a God-given right to global preeminence. The other is trickier. In effect, it puts “white” before America First. This is not something Trump especially wanted to say. Like many racists, he likes to think of himself as “the least racist person that anybody is going to meet.” But he fully understood that very many of his consumers wanted that qualifier to be there, some explicitly, most implicitly. What the customer wants, the customer gets.

In the aftermath of the Capitol disaster, and of Trump’s loss of both the presidency and the Senate, the vestigial Republicans had to execute an impossible maneuver: pulling away from him while retaining the loyalty of his admirers. The gambit was to play up the innocence of Trump’s fans, to picture them as poor gullible people misled by a bad man. “The mob was fed lies,” said Mitch McConnell. “They were provoked by the president and other powerful people.” They were, in other words, misled in both senses—deceived and ill-directed. The utility of this story is that it downplays the guilt not just of McConnell himself and the vast majority of his party in Congress, but of what is now the Republican base. It implies that under better, more responsible leadership, the base will revert to a norm of truth-seeking reasonableness (as defined by responsible and respectable billionaire-funded think tanks). But it evades the much more complex relationship of truth and lies, of the real and the unreal, that is at the heart of Trumpism.

It is obvious that Trump lied prodigiously and that his construction of “alternative facts” has deliberately and successfully obliterated for his supporters the distinction between the fake and the genuine. But pure falsehood alone would not have created the bond between Trump and his base. What he managed to do was simultaneously to erase the distinction between the valid and the bogus and to remake it. He abolished it in the realm of events, of facts about what is happening. But he remade it in the realm of collective identity. He replaced the actual with the authentic. What is real is not what is going on. It is who “we” are.

“Real Americans, right here. Americans!” screamed the Capitol rioters. “Every corrupt member of Congress locked in one room and surrounded by real Americans.” This is a phrase that Trump began to pick up in 2014 as he started to retweet fans urging him to run for president: “Mr. Trump is a real American patriot”; “a president who has proof he is a real American”; “We need you to run for POTUS. we need a REAL American, one with the same values that built this country. GO TRUMP 2016”; “We need a real American to run our country.” Helpfully, Trump’s handle on Twitter was @realDonaldTrump. But the order of influence is important here. Trump is not telling his market that they are the real people; they are telling him that he is the one who can embody and validate their already well-formed self-identification as the genuine American article.

It is not wrong to call the allegations of a rigged election, as Timothy Snyder has done, the “big lie” of Trumpism.2 But it’s a lie that was already there. It is, in artistic terms, a readymade, a found object. It is, perhaps aptly, Trump’s version of the urinal that Marcel Duchamp renamed Fountain. He just put an existing notion of fraudulence on a pedestal and gave it a title: the Steal. But the object itself is both old and mass-produced. It is made by fusing the idea of an entitlement to privilege—which is being stolen from white Americans by traitors, Blacks, immigrants, and socialists—with the absolute distinction between real and unreal Americans. The concern is not, at heart, that there are bogus votes, but that there are bogus voters, that much of the US is inhabited by people who are, politically speaking, counterfeit citizens. Unlike us, they do not belong; they cannot be among the “we” who get to choose the king.

Trump, as so often in his career, didn’t build this attitude—he branded it. He put his name on it. What this did for his people was to allow them to recognize themselves not as citizens, or even as partisans, but as a crowd. Given that his image was significantly shaped on television and through social media, it was counterintuitive for Trump to place so much emphasis on the old-style physical rally. But he understood how crucial it was to allow his consumers not just to see him, but to see one another. Whether by being there in the flesh or through experiencing the thrill vicariously on TV or online, they were able to recognize one another, both for who they were and who they were not: the Mexicans, the Muslims, the lamestream media.

This crowd was a figment of America itself, full of patriots like themselves but also, in the Trumpian discourse about immigration, full up. The rally, like the imagined America Trump presented to it, was what Elias Canetti called a “closed crowd”: “The entrances to this space are limited in number, and only these entrances can be used…. Once the space is completely filled, no one else is allowed in.” Canetti noted that the enclosure of the crowd “sacrifices its chance of growth, but gains in staying power.” That sounds like an accurate description of Trump’s base—it did not grow very much but it showed extraordinary resilience. Canetti also suggested that this kind of crowd “sets its hope on repetition.” It has to disperse but knows it will return:

The building is waiting for them; it exists for their sake and, so long as it is there, they will be able to meet in the same manner. The space is theirs, even during the ebb, and in its emptiness it reminds them of the flood.

That also sounds like an accurate summation of the likely afterlife of the Trump presidency among those who believe the American republic exists exclusively for their sake.

What can Joe Biden set against the closed crowd that Trump assembled, so as to thwart its desire for a repetition of the flood that almost inundated American democracy? His inauguration, of course, had no crowd. But this forced him to conjure the absent people through symbolism. He created three imaginary throngs. The first was the field of nearly 200,000 US flags laid out on the National Mall to stand for those who would have been there. The second was the one that always outnumbers the living: the crowd of the dead. Biden and Harris ritually summoned the dead of the pandemic in the ghostly form of four hundred lights set around the Lincoln Memorial’s reflecting pool, to represent what were then the 400,000 victims of the virus and of the malign misgovernment that so increased their number. Biden summoned them again in the pause for silence he called for during his inaugural address. He became the chief mourner at an imaginary mass funeral, calling up in light and silence those who have been lost in Trump’s dark clangor.

There was also another, more subtle image in that address. He reached (no doubt under the influence of the historian and sometime Biden speechwriter Jon Meacham, who has popularized the phrase) for Saint Augustine’s notion of a people in the City of God: “A multitude defined by the common objects of their love.” Augustine’s phrase is actually more complex: “A multitude of rational beings united by a common agreement on the objects of their love.” Biden was probably wise, in the moment, to dodge the questions of rational beings and common agreement. But the insertion of “defined” has deep meaning. Trump allowed a “people” to define itself by the rights of birth. The poet Amanda Gorman in her inaugural ode redefined those rights: “Change [is] our children’s birthright.” The entitlement she evoked is one that is not inherited by blood or nationality but created by struggle as a legacy from this generation to the next. This was also Biden’s appeal—to the notion of a people defined not by being but by doing, not by what it is but by what it strives to achieve. To live up to this, the new administration must set out clearly the objects it is working for and be relentless in attaining them.

That word “multitude” is part of this redefinition. A multitude is not a closed crowd. It is multiform and multifold. If there is a real America, this is what it must be. To keep the crowd from overwhelming its democracy, that idea of a variousness that does not imply or justify inequality must at last be given real substance. Only an America that is a true multitude can be safe from the mob.

—January 28, 2021

This Issue

February 25, 2021

The Stench of American Neglect

Bildungsonline

-

1

“Be Ready to Fight,” The New York Review, February 11, 2021. ↩

-

2

“The American Abyss,” The New York Times Magazine, January 9, 2020. ↩