When, Mary Beth Norton asks, did the American Revolution begin? The question is surprising, largely because the answer seems to have been settled long ago—by people who actually participated in it. The revolutionary story that most of us learned at school usually starts in 1760, with the coronation of George III. The colonists loved him. They expected him to defend the British constitution, champion Protestantism, and promote commercial prosperity throughout the empire.

But then, according to this familiar narrative, everything slowly turned sour, and within a few years the new monarch and his supporters in Parliament managed to alienate Americans who pledged their undying loyalty to Great Britain while at the same time protesting, often by rioting in port cities, the notion that a legislature in which they had no representation could force them to pay taxes. A revolutionary spirit gradually gathered momentum throughout America. Angry colonists opposed the Stamp Act (1765), the Townshend duties (1768), and the Tea Act (1773), a series of parliamentary statutes that taxed various print materials such as newspapers and popular consumer items imported from Great Britain.

This account of revolution leads almost inevitably to the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775. Commentators at the time favored a metaphor of maturation: American adolescents had come of age, announcing in a united voice that they could no longer tolerate British control. The revolutionary seeds planted early in the reign of George III reached their natural and logical fulfillment with the Declaration of Independence.

Norton, a distinguished scholar of early American history, advances a different revolutionary story. For her, it does not make sense to claim that the revolution began almost fifteen years before colonial militiamen fired on British troops at Concord. The revolution, she argues persuasively, started in what she calls the long 1774, which includes parts of 1773 and 1775. By focusing on those months of rapidly accelerating and fundamental political change, she recasts the oft-repeated account of how colonists evolved from loyal subjects of the crown in 1760 to determined revolutionaries in 1776. Norton also helps us understand how difficult it was for many Americans to abandon political beliefs about an ordered monarchical system that they had come to take for granted.

The interpretive challenge turns on how we define the moment of transition. Scattered protests, even if they involve violence, do not generally signal the start of a revolution. Unhappy people usually find ways to back down, and impassioned rhetoric about alleged political wrongs usually yields little more than a return to the status quo. Genuine revolutionary change requires widespread recognition that the regime in power is vulnerable. In this situation, emboldened and discontented people forge new solidarities. They find ways to communicate their grievances to strangers who live in distant places.

From there it is an easy step for people committed to an imagined common cause to begin arming in defense of shared principles. The revolutionary moment occurs when they realize that there is no turning back. A single incident, at once unanticipated and alarming, often serves as a tipping point. Inchoate anger and frustration spill out onto the streets. Small communities join the resistance, and people who had previously ignored the gathering storm are forced to decide—often publicly—whether they are prepared to sacrifice their lives and property to escape insufferable political oppression.

Even if we accept 1774 as the defining moment of revolutionary change, we still might wonder whether it is warranted to lop off the earlier period, when Americans protested against taxation without representation.* Perhaps the Stamp Act crisis or the Boston Massacre in 1770—an incident in which British soldiers killed five ordinary Americans—might retain a place in the revolutionary story as harbingers of growing discontent that led eventually to independence. However plausible that claim is, Norton is correct that it does not hold water. For one thing, protests against parliamentary taxation before 1774 were highly local, and even when colonists rioted, this did not generate widespread mobilization or the creation of a large-scale revolutionary network. These were dramatic episodes, but they did not hint at an impending collapse of imperial authority.

The British had a long history of dealing with confrontations of this sort. They effectively addressed such problems in England, Ireland, and Scotland through a process of incentives and punishments that successfully contained local anger. The Boston Massacre, for example, did not hasten Americans along a path to Lexington and Concord. Rather, the killing of civilians sparked a round of negotiation and compromise, and for the next three years the colonists seemed so complacent that Samuel Adams—often depicted as the firebrand of revolution—feared that they had lost interest in resistance. Between 1770 and 1773 they purchased imported British goods in record quantities. What had occurred in Boston amounted to little more than a small perturbation within a secure imperial regime.

Advertisement

An argument in favor of an extended period of revolutionary gestation might take a different approach. It could stress the experiences of figures such as George Washington, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin. Were these men not calling for greater colonial autonomy and thereby anticipating an eventual break with the mother country? This proposition confuses complaints about annoying parliamentary taxes with personal ambition within an imperial system reluctant to distribute offices and honors to colonists, who were viewed by Britain’s leaders as second-class subjects.

This condescending attitude infuriated Americans shut out of the patronage network. Washington, for example, retired from military service because he was denied a regular commission in the British army. During the 1760s Adams was a rising star in the Massachusetts legal community, but talented as he was, he could not compete with Thomas Hutchinson, the colony’s lieutenant governor, for royal favor. Adams complained bitterly in his diary that Hutchinson had “grasped four of the most important offices in the province into his own hands.” As postmaster general of America, Franklin enjoyed the lucrative perks of appointive office, and it is no surprise that he remained ambivalent about colonial resistance until he was stripped of the position in 1774. Francis Bernard, royal governor of Massachusetts during the 1760s, proposed a clever way to address the problem of frustrated ambition. He called for the creation of a kind of American House of Lords filled with wealthy provincials who, instead of whining about taxes, would compete to have “Baron prefixed to their Name.”

The most serious problem with the claim that the revolution resulted from a long-simmering sense of injustice is that ordinary Americans initially showed very little interest in confronting imperial authority. Resistance to the Stamp Act and the killing of civilians during the Boston Massacre certainly got attention, but even at the moment of greatest discontent, colonists hesitated to voice support for urban protest. In many places people feared that a few radicals were stoking a political crisis that could destabilize an imperial system responsible for widespread prosperity. The possibility that clashes with British appointees during the 1760s would provoke extensive mobilization was very low. Andrew Burnaby, a British clergyman who traveled through the colonies in 1759, had written that the Americans would never overcome “the difficulties of communication, of intercourse, [and] of correspondence,” and concluded that “fire and water are not more heterogeneous than the different colonies in North America.”

The political landscape changed dramatically on the night of December 16, 1773, when the destruction in Boston Harbor of tea imported by the East India Company made the scattered protests that had gone before suddenly seem irrelevant. It took several months for the full implications of the Tea Party to play out in England and America. As Norton explains, the incident served as a political catalyst for the subsequent spread of popular resistance throughout the colonies.

To be sure, an outpouring of anger greeted the arrival of the tea. Everyone knew that by purchasing the imported tea, they would be compelled to pay a tax set by Parliament, a body in which they had no representation. One handbill circulating in the streets of Boston reflected the public mood:

Friends! Brethren! Countrymen!… That worst of Plagues, the detested TEA…is now arrived in this Harbour; the Hour of Destruction or manly Opposition to the Machinations of Tyranny stares you in the Face.

As with the earlier protests, however, many Americans expressed reservations about what a group of men dressed crudely as Indians had done in Boston Harbor. They worried that extremists had taken protest to an unacceptable level. Of course, no colonists wanted to pay taxes on their favorite drink. But the tea was private property, and not a few people counseled the City of Boston to compensate the East India Company for the lost cargo. One commentator in Virginia registered misgivings about the “hasty inconsiderate determination of the populace to the northward,” which could promote “alarming consequences.” Another contemporary warned of the “Sons of Riot and Confusion.”

Everyone in Boston expected Parliament to punish the city for this brazen attack on private property. They assumed that negotiations with officials in London would result in censure, and then, after emotions had cooled, relations with the mother country would return to normal. That did not happen. As has occurred so often in the long history of imperial regimes, the leaders of Parliament decided to teach the troublesome Americans a lesson. A mere warning that they should behave themselves in the future would not serve the purpose. Obedience required a show of force.

Speakers in the House of Commons could hardly contain themselves. They insisted that it was time to crush the people of Boston for their audacity. One member of Parliament announced that “the flagitiousness of the offense”—the dumping of the tea into Boston Harbor—justified the belief that “the town of Boston ought to be knocked about their ears, and destroyed.” Political leaders in London insisted that the Americans deserved no special consideration, since they alone were responsible for the crisis. Another MP observed that “the Americans were a strange set of People, and that it was in vain to expect any degree of reasoning from them.”

Advertisement

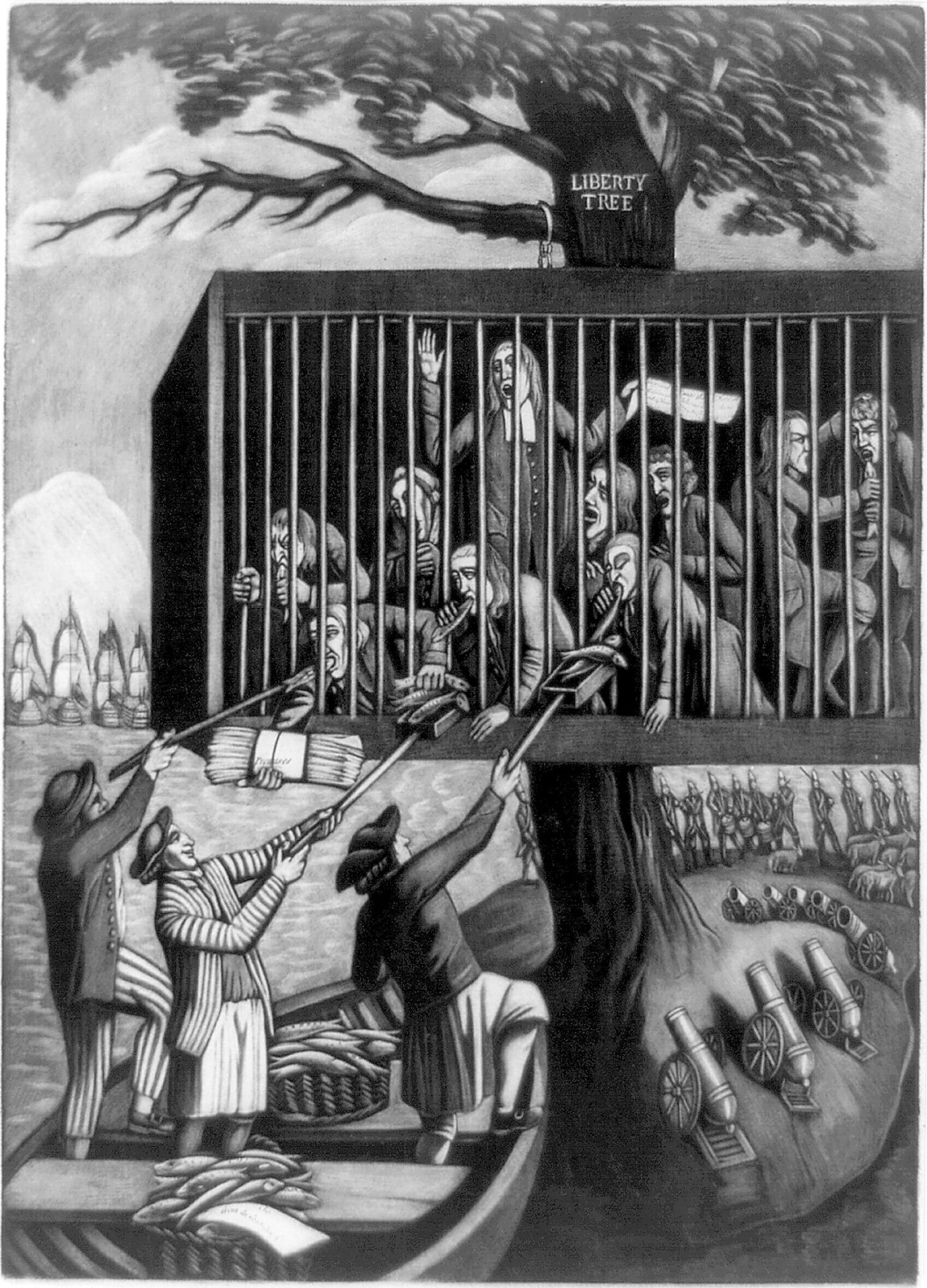

The punishment was far worse than anyone had anticipated. It was spelled out in four acts known in England as the Coercive Acts. Americans called them the Intolerable Acts. Richard Henry Lee, an influential Virginian, described the legislation as a “shock of Electricity,” causing universal “Astonishment, indignation, and concern.” The most vexing—the Boston Port Act—closed the city to all commerce; other acts restricted town meetings throughout Massachusetts to once per year and gave the royal governor of the colony enhanced authority over political appointments. Trade now had to flow through Salem, which greatly added to the cost of doing business. More disconcerting, the legislation created widespread unemployment in Boston, where many poorer residents worked on the docks.

Bostonians pointed out that it was grossly unfair to penalize the entire population of the city for a crime carried out by a small group, but British officials expressed no sympathy. They suspected that the Americans had absorbed a spirit of democracy. Hutchinson reported to the men who ran the empire, “I see no prospect…of the government of this province [Massachusetts] being restored to its former state without the interposition of the authority in England.” When Boston officials asked how long the city would have to endure closure, Lord North, chancellor of the exchequer, responded with calculated vagueness, “The test of the Bostonians will not be the indemnification of the East India Company alone, it will remain in the breast of the King not to restore the port until peace and obedience shall be observed.”

The show of force did not intimidate the colonists. British leaders greatly increased the chance that the situation in America would explode by appointing a military officer, Thomas Gage, as governor of Massachusetts. He seemed to possess the kind of toughness needed to pacify rebellious colonists. Gage informed George III that the Americans “will be Lions, whilst we are Lambs, but if we take the resolute part they will undoubtedly prove very meek.” And true to his word, he arrived in Boston on May 13, 1774, accompanied by a large contingent of troops. Not surprisingly, an army of occupation served only to further enflame the populace.

Within weeks imperial authority outside Boston collapsed. Officials appointed by the crown resigned; committees were formed throughout the colony to fill the administrative vacuum. Militiamen began to drill. Local bodies enforced a prohibition on drinking tea. The celebrated orator Edmund Burke had predicted this would be the result of the Coercive Acts. “Have you considered,” he asked the House of Commons, “whether you have troops and ships sufficient to enforce an universal proscription to the trade of the whole Continent of America?” When it became clear that his audience was determined to bring the Americans to heel, Burke concluded, “This is the day, then, that you will go to war with all America, in order to conciliate that country to this; and to say that America shall be obedient to all the laws of this country.” No one listened.

During the summer of 1774, it became clear that the punitive policies championed by the North administration were stunningly counterproductive. Without doubt, decisions made in London had accelerated the formation of a genuine revolutionary network in America. The suffering of Boston soon became the cause of colonists outside the city. They sensed that if they did not support resistance, they too might soon find themselves living under military occupation. Farmers in Gorham, a small village in Maine (then part of Massachusetts), for example, resolved that

we of this town have such a high relish for Liberty, that we all, with one heart, stand ready, sword in hand, with the Italians in the Roman Republick, to defend and maintain our rights against all attempts to enslave us, and joyn our brethren, opposing force to force, if drove to the last extremity, which God forbid.

People living in distant colonies sent food to the unemployed workers of Boston. The details of what was actually happening in the city did not matter. Political solidarity was an act of imagination. Britain’s show of toughness encouraged ordinary people from New Hampshire to Georgia to reach out to other Americans who before this moment had been total strangers. They began to talk of themselves as if they were no longer British, or at least not as British as they had been before Gage and his army arrived in Boston.

The spreading resistance movement persuaded political leaders of the various colonies to meet in Philadelphia in early September 1774. The first Continental Congress brought Americans of very different backgrounds together. None of them had a definite sense of where fast-moving events were taking them. Prominent figures such as Joseph Galloway, the Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly, presented powerful arguments for reconciliation. Some of his colleagues sensed, however, that the moment for constructive compromise had passed. The people needed direction. Otherwise the defense of American rights would fragment.

The Continental Congress devised a brilliant solution. On October 20, it authorized the creation of the Continental Association, which bound the thirteen colonies in order to bring additional pressure on Parliament by cutting off trade with Britain. Boycotts had been tried before, but because of local jealousies and competition among merchants, they had failed to achieve their purpose. The Continental Association was different. It established precise dates for the cessation of the importation of British goods. It also set down regulations for trade with the mother country. According to the Congress, the goal of the commercial regulations was “to obtain redress of these grievances which threaten destruction to the lives, liberty, and property of his majesty’s subjects in North America.”

The problem was how to enforce these regulations. How could the Congress unite thousands of small communities in a common effort? The answer appeared in the eleventh article of the Continental Association, which transformed the entire character of the resistance movement. A document of such fundamental significance in the history of the United States merits close reading:

That a committee be chosen in every county, city, and town, by those who are qualified to vote for representatives in the legislature, whose business it shall be attentively to observe the conduct of all persons touching this association; and when it shall be made to appear, to the satisfaction of a majority of any such committee, that any person within the limits of their appointment has violated this association, that such majority do forthwith cause the truth of the case to be published in the gazette; to the end, that all such foes to the rights of British-America may be publicly known, and universally contemned as the enemies of American liberty; and thenceforth we respectively will break off all dealings with him or her.

The association signaled the moment in a new revolutionary narrative when ordinary Americans realized that there was no turning back. At the time, almost no one was calling for independence. The groundwork for that break, however, was now in place. The crucial move was that the Continental Congress gave ordinary Americans the responsibility for monitoring commercial violations, but as one might have predicted, these local committees quickly assumed additional duties. By 1775 they were legitimizing popular resistance to imperial rule and channeling mobilization. The Continental Association did something even more important: it revealed the pressing need for some form of centralized authority to oversee the actions of thirteen very different colonies. Unity was essential to sustaining a common cause.

Norton accomplishes something more than a revision of the traditional story of the coming of the American Revolution. She reminds us that even when it seemed inevitable that continuing protest would lead to violent confrontation with British troops, there were intelligent, articulate people in America who wanted desperately to head off the crisis. Their concerns often receive little attention, since the focus of most histories of the period is on the revolutionaries.

It was hard for people such as the Reverend Thomas Bradbury Chandler, an Episcopal minister from New Jersey, to break with the comforting security of a monarchical regime. He wrote an immensely popular pamphlet called The American Querist, which consisted of one hundred questions designed to challenge assumptions driving the resistance movement. He was especially worried that political zealots were intent on silencing dissent. One of Chandler’s queries asked “whether Americans have not a right to speak their sentiments on subjects of government.” In another he inquired:

Whether it be not a matter both of worldly wisdom, and of indispensible Christian Duty, in every American, to fear the Lord and the King, and to meddle not with them that are GIVEN TO CHANGE?

Writers of Chandler’s persuasion advanced solid arguments that embarrassed revolutionary leaders, who did not want to go on record advocating the suppression of free speech. Loyalist writers might have gained greater popular support had they shown a better understanding of the forces that were energizing the resistance movement. Instead, they were defending a social system that no longer made sense to many Americans.

The committees that enforced nonimportation seemed to Loyalists to invite anarchy. Mob rule, Chandler and his allies claimed, would destroy the ordered security of a monarchical world. The Reverend John Bullman, an Episcopal rector in Charleston, South Carolina, railed against the notion that ordinary men were capable of judging “the Fitness or Unfitness of all persons in power and Authority.” Bullman rejected the idea that a person “who cannot perhaps govern his own household, or pay the Debts of his own contracting,” should “dictate how the State should be governed.” Chandler shared this opinion. He asked, regarding “interested, designing men…or ignorant men, bred to the lowest occupations,” whether “any of them [were] qualified for the direction of political affairs, or ought to be trusted with it.” No was the expected answer to the rhetorical question. As the events of 1774 demonstrated, however, a great many Americans of the lowest occupations strongly disagreed.

One can appreciate why loyalists equated revolutionary change with disorder. They sensed that events were leading to a republican form of government in which people of ordinary social status would have a meaningful political voice. Their fears were misplaced. Mobilization for the fight for independence did not promote anarchy. Americans followed the Continental Association’s regulations, sacrificing the imported consumer items that brought them so much pleasure. The revolutionaries who came forward in 1774 would have found it hard to understand modern Americans who define liberty as the right to do whatever they please during a time of national crisis even though they know that their self-indulgence threatens the welfare of the larger community.

-

*

The runup to independence is discussed in my “What Time Was the American Revolution? Reflections on a Familiar Narrative,” in Experiencing Empire: Power, People, and Revolution in Early America, edited by Patrick Griffin (University of Virginia Press, 2017). ↩