In 1819 the French inventor Cagniard de La Tour gave the name sirène to the alarm he had devised to help evacuate factories and mines in case of accident—in those days all too frequent. The siren, or mermaid, came to his mind as a portent, a signal of danger, although it might seem a contradiction, since the sirens’ song was fatal to mortals: in the famous scene in the Odyssey, Odysseus ties himself to the ship’s mast to hear it, and orders his men to plug their ears with wax and ignore him when he pleads to be set free to join the singers on the shore. Homer does not describe these irresistible singers’ appearance—only their flowery meadow, which is strewn with the rotting corpses of their victims—but he tells us that their song promises omniscience: “We know whatever happens anywhere on earth.” This prescience inspired Cagniard: he inverted the sirens’ connection to fatality to name a device that gives forewarning.

In Greek iconography, the sirens are bird-bodied, and aren’t instantly seductive in appearance but rather, according to the historian Vaughn Scribner in Merpeople, “hideous beasts.” A famous fifth-century-BCE pot in the British Museum shows Odysseus standing stiffly lashed to the mast, head tilted skyward, his crew plying the oars while these bird-women perch around them, as if stalking their prey: one of them is dive-bombing the ship like a sea eagle. An imposing pair of nearly life-size standing terracotta figures from the fourth century BCE, in the collection of the Getty Museum, have birds’ bodies and tails, legs and claws, and women’s faces; they too have been identified as sirens (see illustration below).

Classical myth features many ferocious female monsters, such as gigantic Scylla, girdled by twelve limbs and snapping dogs’ heads, who is condemned to seize and devour passing sailors. The imagery of sirens overlaps with that of harpies, foul-smelling raptors whose name means “the snatchers.” By contrast, Poseidon, the god of the sea, comes with a whole train of delightful nymphs (nereids), tritons, and merbabies like bathing cupids, many with fishes’ tails and wreathed in seaweed fronds and shells. When these ancient traditions about watery creatures met more northerly, fish-tailed, often sweet-voiced seductresses, such as the freshwater spirits of wells and rivers—undines, rusalkas, and Loreleis—the Greek sirens’ powers became identified with sexual temptation, and the two forms became conflated. One medieval illuminator of Ovid pictured sirens as flying fishes.

Scribner’s book is compact, richly referenced, attractively produced, and wonderfully illustrated with more than a hundred plates, many unfamiliar (to me) and in full color. A professor at the University of Central Arkansas, he is chiefly curious about shifts in intellectual inquiry as he chronicles beliefs about mermaids, including reports of sightings, exhibitions of discovered specimens, scientists’ views, and popular cultural artifacts from films to dolls.

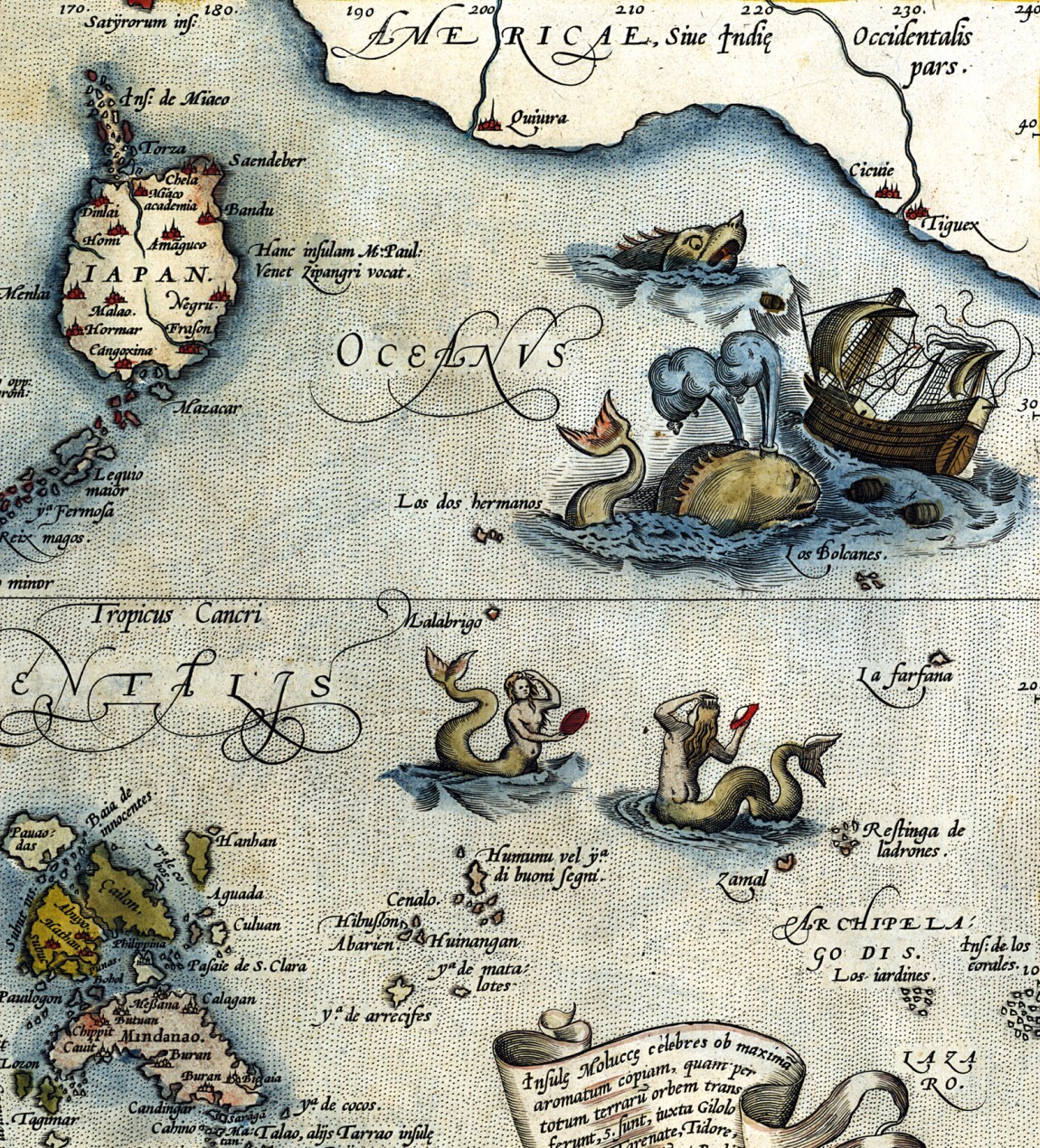

In the first of six concise chapters, Scribner explores the mermaid’s appearances in medieval documents, where the authors stigmatize her as a symbol of fallen humanity, and he then contrasts this view with the wonder and curiosity that, in the early modern period, dominated the motives of explorers and conquerors—and mapmakers, who studded their gorgeous artifacts with monsters and prodigies: “Here Be Mermaids” is a marine cartographer’s equivalent of “Here Be Dragons.” Scribner then attends to scientific attempts in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—and even into the twentieth—to ascertain the reality and nature of these mythic figures, telling the story of the fairs and shows where ostensibly captured mermaids, stuffed and mounted, were exhibited. He concludes with accounts of films, advertisements, pageants, and theme parks, demonstrating growing rather than fading interest with mermaids in the present day. Yet in its revelations of the appetite for delusion among so many, even as they pursued greater understanding, it’s a tale that is especially disturbing at this time of deliberate misinformation.

It was around 800 CE, Scribner suggests, that classical sirens began to fuse with the lore of water spirits who radiate dangerous magic in Slavic, Norse, German, and Celtic myths and fairy tales. Mermaids, sometimes in the form of sheela-na-gigs (female figures holding up their double tails and seemingly exulting in this self-exposure), were carved on roof bosses and misericords in Christendom’s holy sites, often, but not always, placed clandestinely. Beautiful and monstrous, they embodied the dangers of sin but also the powers of enchantment; flaunting their sex so flagrantly on portals and thresholds, they perform a kind of protective magic. This equation between beauty, desire, sex, and sin structures the figure of the mermaid: bestiaries and incunabula include scores of delightful vignettes of mermaids and their wicked seductions—the artists thereby having it both ways, dwelling on the pleasures of the temptress while sternly decrying them. Surprisingly, Scribner doesn’t mention the classic text on this theme, Dante’s nasty nightmare in Purgatorio XIX, in which a dolce sirena (sweet siren) appears to him, singing; then, still in the dream, Virgil intervenes and tears off her clothes, and the stench from her ventre (belly or innards) overcomes Dante and he wakes.

Advertisement

Hans Christian Andersen wrote the most celebrated variation on the mermaid tradition and took its punitiveness much further, when in “The Little Mermaid,” his 1837 fairy tale, the love-smitten protagonist comes to a tragic end, dissolving into sea foam while her beloved prince flourishes unconcerned. (This twist echoes the Eastern European tradition of water sprites dwelling in rivers or lakes, as in Czech fairy tales, such as those collected and written by Božena Němcová and Karel Jaromír Erben, and dramatized in Dvorák’s magnificent, harrowing 1901 opera Rusalka.) As Andersen tells the story, the Sea Witch makes a bargain with the young mermaid—the witch will give her a human form in return for her bewitching voice: “Stick out your little tongue, and let me cut it off in payment.” The Sea Witch warns her:

Your tail will divide and shrink, until it becomes what human beings call “pretty legs.” It will hurt; it will feel as if a sword were going through your body…. Every time your foot touches the ground it will feel as though you were walking on knives so sharp that your blood must flow.

Such a scene, with its menstrual undercurrent, inculcated an understanding of women’s lot; I regret to say that as a child I thrilled to this sadism. I was not alone. Like many fairy-tale heroines, mermaids, as Scribner is aware, have long acted as a prime tool in the training of women and the gendering of culture.

Even as the classical raptor-like portent of death faded from memory, the siren song remained the irresistible lure of fish-tailed enchantresses. On maps and in travelers’ tales of marine wonders, solitary mermaids are glimpsed, often holding a mirror and a comb as they swim about in the sea. In antiquity, these were attributes of Aphrodite who, in the sculptural pose called “Venus Anadyomene,” has just emerged from her bath and is wringing out her hair. She lent these features to Christian interdictions of pleasure, and her grooming came to signify vanity and lust: on the Angers tapestry of the Apocalypse, the Whore of Babylon even appears with long blond hair, comb, and mirror, and, as Scribner often notes of mermaids, a toned midriff. The routines of self-care that a mermaid performs indicate that something is in progress: suggestively, she embodies a moment of anticipation or repair; as she dresses her hair and sings, she is filled with the active, kinetic energy of the erotic and hints invitingly at pleasures to come or already enjoyed.

The solitariness of the mermaid persists as a motif from the Middle Ages onward. On maps she suggests the lure of the terra incognita that explorers are setting out to encounter; she’s a symbol of “my new-found-land,” as John Donne calls his beloved, and of the knowledge that is available to those who are brave enough to seek it. Part of the sirens’ charm lies in their implied neediness for company—for a playmate. The famous sculpture of the Little Mermaid in Copenhagen, which has become the city’s totem and a national emblem, sits alone, demure and forlorn, but even she, almost a child and the very opposite of a bold temptress, is positioned expectantly, as a lookout on her rock at the entrance to the harbor.

Merpeople joins a shelfload of books about mermaids, for these creatures of myth and folklore have become a contemporary craze, and not only with little girls; as Scribner declares in his opening sentence, “merpeople are everywhere.” With his interest lying chiefly in the history of scientific and popular approaches to his subject, his literary range doesn’t extend much beyond Andersen—in a book of this brevity, it would not have been possible. But it is a lacuna, and Merpeople will be much enriched if read alongside an anthology such as The Penguin Book of Mermaids (2019), for which the fairy-tale scholar Cristina Bacchilega and the Hawaiian specialist Marie Ahohani Brown have gathered a feast of myths and legends from original sources the world over, while in Atlante delle Sirene (Atlas of the Sirens, 2017)—another delectably illustrated volume, awaiting translation into English—Agnese Grieco offers more philosophical and poetic reflections.

The long history of reported encounters with mermaids inspired Scribner to use computer technology to plot such sightings on a world map. He can’t resist quoting affirmations from such notables as David Attenborough, who comments in his l975 book, David Attenborough’s Fabulous Animals, that “the stories of mermaids persist and have some ring of truth about them.” (I suspect this gentle claim was made for the benefit of the younger reader.) Speculation about realms under the sea, and dependence on water sources—lakes and wells and streams—gave rise to a multifarious population of watery beings, including rusalkas and undines and goblins.1 Scribner offers a rapid tour d’horizon and enlists examples of water spirits from North America before settlement by Europeans, South Africa before colonization, Japan, India, the Caribbean, and Australasia.

Advertisement

Folklore material of this kind often enshrines preindustrial societies’ respect for natural forces; as repositories of organic, ecological knowledge, such tales deserve more attention than they have been given hitherto. In a fine recent novel, The Mermaid of Black Conch,2 the Trinidadian writer Monique Roffey develops such folk beliefs in a contemporary setting, when a dark-skinned, mysterious fish-woman is caught by rich white trophy hunters out for excitement on a small Caribbean island. She’s rescued by a young local fisherman, who discovers she’s a revenant from the precolonial past and remembers the language and culture of the Taino, the indigenous people of the region.

In the nineteenth century the possibility that mermaids might represent evidence of prehistory and even a key to human evolution was seriously entertained by scientists, much to Scribner’s amusement—and alarm. In the archives of the Royal Society and the pages of the Gentleman’s Magazine, Scribner found serious correspondence, expressed in the most scrupulous scientific terms, identifying any number of life forms with the mermaid of myths. He quotes a letter from Linnaeus, written to the Swedish Academy of Science in 1749, “urging a hunt in which to ‘catch this animal alive or preserved in spirits.’… Perhaps these creatures could reveal humankind’s origins?”

The Enlightenment’s scientific inquiries into hearsay and surmise had a paradoxical—and, to me at least, bitter—result, since it betrayed the very principles that spurred on the search in the first place: the exhibition of alleged mermaid mummies and skeletons, including heads, hands, and ribs, as proof positive of their existence. In a chapter called “Freakshows and Fantasies,” Scribner uncovers unlikely claimants—species from the deep that resemble eels and lizards, which eager scientists identified as sirens. The grisly, wizened, and contorted effigies concocted in Japan, often from baboon and salmon body parts, couldn’t be further from the erotic promise of the sea nymphs of story.

And yet in 1842, when P.T. Barnum joined in the bonanza and purchased a “Feejee Mermaid,” as he called the grotesque, grimacing figure, crowds flocked and paid to see it in London, New York, and elsewhere. Barnum used to seem a colorful, larger-than-life character, but with today’s public charlatanry in mind, he epitomizes a real danger. “The shrewd businessman,” Scribner writes,

utilized the very network of newspapers that had maintained a debate over the legitimacy of merpeople over the preceding decades to announce his Feejee Mermaid to the world. And he was smart about it, sending supposed scientific accounts from the American South (written by himself).

Barnum followed this up with testimonials and eyewitness reports about “one of the greatest curiosities of the day” in a cascade of leaflets and flyers.3

Scribner documents the prurience, gullibility, and hucksterism of newspapers of the time, which he has combed online: he’s an adept of databases, declaring that he received over 95,000 results from his searches of The New York Times and other papers, and is consequently able to state confidently that there were “31 verified merpeople sightings” between 1800 and 1900, twenty-four of them in the first fifty years. They burgeoned and became entangled with more sensational reports of fakes and frauds. A hugely successful show like Ripley’s Believe It or Not! deliberately reveled in the outrageousness of the exhibits, and make-believe was an essential part of the enjoyment, as I experienced when meeting a mermaid—in a long blond wig and a silver tail—in the 1980s at one of the show’s venues on the West Coast.

Fantastic beliefs, in the form of false claims and urban legends, have been traveling irresistibly—you might say virally—since the eighteenth century, mimicking and mutating with subtle shifts adapted to circumstances. The effect today has been amplified by social media; mermaid sightings rank in popularity alongside those of aliens, angels, fairies, and unicorns. The problem lies with our human curiosity and our intellectual need to verify something that our imagination conceives, to test the idea in the laboratory of direct experience. But the outcome inverts this purpose, and the figment, actualized, replaces reality and then, in a spiral of counterfeits, distorts knowledge itself.

As the title Merpeople indicates, Scribner wishes to include the male of the species—as in the case of tritons and mermen—and he alludes briefly to the Mesopotamian figure of Oannes, a majestic, bearded, fish-tailed sea divinity who teaches humanity wisdom—writing and the arts and sciences. “Orcas” could have been mentioned, too: one appears in jewels and a splendid turban in an illustration in Chet Van Duzer’s Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps (2013),4 a rich source for the watery imaginary, on which Scribner has drawn, as he acknowledges. But material about mermaids’ male counterparts is sparse, and not all male sea creatures are as benign as Oannes: Proteus, whom Homer calls the Old Man of the Sea, savagely rapes Thetis, the sea goddess; the child of this union is Achilles. As related in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, this myth reveals the metaphorical range of watery beings—allure, mystery, slipperiness, sex, and power.

Scribner also turns his attention to male adventures with mermaids, and gives an entertaining account of several movies, such as Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid (1948) and Miranda (l948). He must have concluded his research before the release of The Shape of Water (2017), Guillermo del Toro’s uncanny, stirring modern fable of two beings at odds with conventional bodily norms. Cowritten with Vanessa Taylor, whose original story was a fairy tale crossing “The Little Mermaid” with “Beauty and the Beast,” del Toro’s film responds to these braided motifs in the mythology of merpeople: the heroine was wounded in the throat as a baby and is voiceless; the hero is a mysterious deep-sea being, close kin to the Creature from the Black Lagoon, who has been captured and subjected to scientific experiments of appalling brutality.

The grim bunker-like setting of The Shape of Water, in a cold war–era US military research facility, presents a powerful and frightening critique of clandestine operations going on in our Western democracies today. As the passionate love between the mute young woman and the mutilated wonder of the deep intensifies, the watery metaphors deepen; during the long consummation (which we are not shown), water pours out of the bathroom where they are making love and floods her lodgings—a visual realization of their ecstatic union. At the end they escape together, plunging into the canal that will lead them to the ocean. He touches her on her wounded throat and she develops gills; it is implied her voice will return.

Familiarity with water—and hence with fluidity and transformation—belongs, alongside their siren song, at the heart of the mermaid’s allure as a figure of desire. Scribner is alert to the contemporary significance of this metaphorical affinity with fluidity: toward the end of his book, he explores the possibilities of gender polymorphousness as performed in events like the annual Mermaid Parade in Coney Island, held since l983. In a jubilant carnival mood, “mermaiders” explore “becoming other.”

However, say the word “mermaid” today to a child and they will, as like as not, imagine a glamour girl who resembles the Little Mermaid of the 1989 Disney film—one of the biggest box office hits ever, with merchandise featuring dolls of the heroine Ariel. Mattel soon brought out a series of Barbies in assorted mermaid costumes, and then tried to make amends to boys, giving “Merman Ken” a sparkly aqua sheath as well. Scribner reproduces these and comments, scornfully, that as “a thin, white merman with platinum blond hair, blue eyes and six-pack abs, Mer-Ken was hardly representative of the diverse audience of children and adults who might purchase him.”

The design of these figures only looks sparkly new; it in fact reprises those early images scattered on Renaissance maps and combines them with many morbid Pre-Raphaelite and Edwardian paintings that render, in slick oil paint, the silvery iridescence of the sirens against the deathly pallor of the sailors whom they have lured and whose corpses they are bearing down below to their secret underwater chambers. But even as Scribner focuses on the sightings, frauds, and artifacts, he does not fail to engage with the quarrel at the core of the mermaid myth: the cultural engineering of femininity.

As Dorothy Dinnerstein crystallized in her 1976 polemic, The Mermaid and the Minotaur:

The images…have bearing, not only on human malaise in general (this they have in common with all the creatures of their ilk—harpies and centaurs, werewolves and sphinxes, winged nymphs, goat-eared fauns, and so on—who have haunted our species’ imagination) but also on our sexual arrangements in particular. The treacherous mermaid, seductive and impenetrable female representative of the dark and magic underwater world from which our life comes and in which we cannot live, lures voyagers to their doom. The fearsome minotaur, gigantic and eternally infantile offspring of a mother’s unnatural lust, male representative of mindless, greedy power, insatiably devours human flesh.

Her book, a feminist classic, issued a call for the fundamental reorganization of society’s gender expectations, especially regarding childrearing.5 Around the world conditions during the pandemic have been especially hard on women—who work as caregivers, housekeepers, and homeschoolers, often unofficially and unpaid. Meanwhile, more than 2.3 million have had to drop out of the US workforce alone in the past year. Dinnerstein’s message has become sadly urgent again.

The close identification of the mermaid with femaleness—especially sexual femaleness—reverberates even in Peter Pan, J.M. Barrie’s story of a small boys’ paradise, Neverland. In the chapter called “The Mermaids’ Lagoon,” they exist as elusive, distant wantons, playful among themselves, but cold and indifferent to the boys; significantly, this is also the chapter in which Smee asks, “What’s a mother?” and then proposes abducting Wendy to fulfill that role for the pirates. Meanwhile, Peter Pan has saved Tiger Lily from Captain Hook and substituted himself as his prisoner. Peter stands on a rock in the mermaids’ lagoon, waiting to be drowned by the rising waters; as he prepares to die, he hears “the mermaids calling to the moon.” The eerie scene ends with Barrie’s homage, in the midst of a boys’ adventure story, to the fin-de-siècle conjunction of Eros and Thanatos: “Peter was not quite like other boys; but he was afraid at last.” And he thinks to himself, “To die will be an awfully big adventure.”

Unexpectedly, an echo of the plangency in Barrie’s children’s story seems to sound in T.S. Eliot’s famous early poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”: “I have heard the mermaids singing each to each.//I do not think that they will sing to me.” And then, in the closing lines, just when the narrator seems to have been admitted to the delights of the mermaids’ imaginary realm, he describes the pleasure interrupted by “human voices”:

We have lingered in the chambers of the sea

By sea-girls wreathed with seaweed red and brown

Till human voices wake us, and we drown.

By switching from the first person to the all-embracing we, Eliot withdraws from the binary erotics of his mermaid vision and enfolds us, readers no longer specifically marked by gender, into the wider reaches of her allure—dissolution, watery obliteration.

This Issue

March 25, 2021

A Gift for the Long Game

The Emergency Everywhere

-

1

For an example, see Teffi, Other Worlds: Peasants, Pilgrims, Spirits, Saints, translated from the Russian by Robert Chandler and Elizabeth Chandler (New York Review Books, 2021), in which Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya (under the pen name Teffi)—a collector and re-visioner of Russian fairy tales and ghost stories heard in childhood—tells of a water spirit who is a terrifying shapeshifter, appearing now as a man, now as a woman, and then vanishing altogether back into the river. ↩

-

2

Leeds: Peepal Tree, 2020. It won the Costa Book Award in the UK in January. ↩

-

3

For more on Barnum, see Nathaniel Rich’s “American Humbug” in these pages, April 23, 2020. ↩

-

4

See my review in these pages, December 19, 2013. ↩

-

5

It has just been published in a new edition by Other Press, with an introduction by Gloria Steinem. ↩