Let’s begin with the body, the corpus to which this six-foot-two lefty was bound. Start with his back. In 1955 he pulled a shift of KP on his last day of basic training and met an industrial-size kettle of potatoes. Hefting it was a two-man job, but the other soldier dropped his end and left him to support its weight alone. Something popped, and the next morning he could barely walk. Try a heating pad, they told him, and an army doctor accused him of malingering. It was never really treated, and the pain never went entirely away. He used a steel back brace for a while, and in the 1970s he sometimes needed a foam neck collar; from middle age on he had to work at a standing desk, spelling himself with long periods of lying on the floor. Only in 2002 did he accept the need for surgery, but by then one disk after another had so fully degenerated that there wasn’t much left to save.

In 1967 his appendix burst; his father had almost died of the same thing, and two of his uncles actually did. Heart disease ran in his mother’s family, and in 1989 he himself had a quintuple bypass. Eventually he had sixteen stents and a defibrillator in his chest. A botched knee operation in 1987 led to insomnia that his doctor treated with large doses of Halcion—sleeping pills that in his case produced a panic fear and near-suicidal depression. It was his second fall into darkness; the first came in 1974, and a third, in 1993, put him into a Connecticut psychiatric hospital. In the new century there was so much pain, and from so many sources, that for a few years he seemed to live on Vicodin, a trouble all its own. “Old age isn’t a battle; old age is a massacre”: so he wrote in Everyman (2006), but for him that massacre had begun long before.

Now add the scars of childhood—though what exactly were they? Everybody has something to blame their parents for. A mother’s smothering love; a father’s overbearing attempts at discipline, lest a promising son should lose his way? Many people grow up in families far more lacerating, suffer an early life more fraught and anxious and disabling than that offered by the warm bath of his homogenous Newark neighborhood. But he’s the one who created Alexander Portnoy. Childhood explains everything and nothing; it gave him his material but not his talent. Though maybe it also gave him his work ethic: the will, as he said, to do the best he could with what he had, and to do it every day. Or perhaps childhood does explain—explain the decisions that led to the later wounds out of which he made his thirty-odd books, that other corpus to which he was chained. I don’t, or don’t only, mean the anger and outrage with which he met the anger and outrage of those early Jewish readers who reacted to the stories collected in Goodbye, Columbus (1959) as if he were spilling family secrets that might confirm the prejudices of the larger society around them. That’s a problem many writers from minority groups run into. Richard Wright certainly did, Ralph Ellison too, and this one would never be done with talking back.

No, there were deeper cuts, for there was also the mid-twentieth-century belief that the responsible thing to do is to accept responsibility. That’s what defined an American man. He saw it in his insurance agent father, he saw it in the men who’d come back from the war, he even saw it in the earnestness of the 1950s literature classroom. So he sought responsibility out. At twenty-five he married a woman named Margaret Williams, a blond midwesterner with two neglected children from a failed first marriage who firmly believed that the world owed her something. She was probably an alcoholic and she was certainly unstable, and he married her only after she tricked him into believing she was pregnant, when experience had already shown him that the relationship was impossible.

He ran toward the demands of what he knew was a nightmare, and then three decades later he did it again: a second marriage, to the English actress Claire Bloom, marrying at her desire, even though their long relationship had been falling apart for years. He wed only the most difficult of his many lovers, and the most vengeful, and he took his own revenge on the first of them in My Life as a Man (1974) and on the second in I Married a Communist (1998). They are not his best books. But in the immediate aftermath of each marriage’s end, in the giddy sense that it was at last over, well, that’s when he wrote most freely. That’s when he finished Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), his millions-selling ode to Onan, and then the intoxicating, appalling comedy of Sabbath’s Theater (1995).

Advertisement

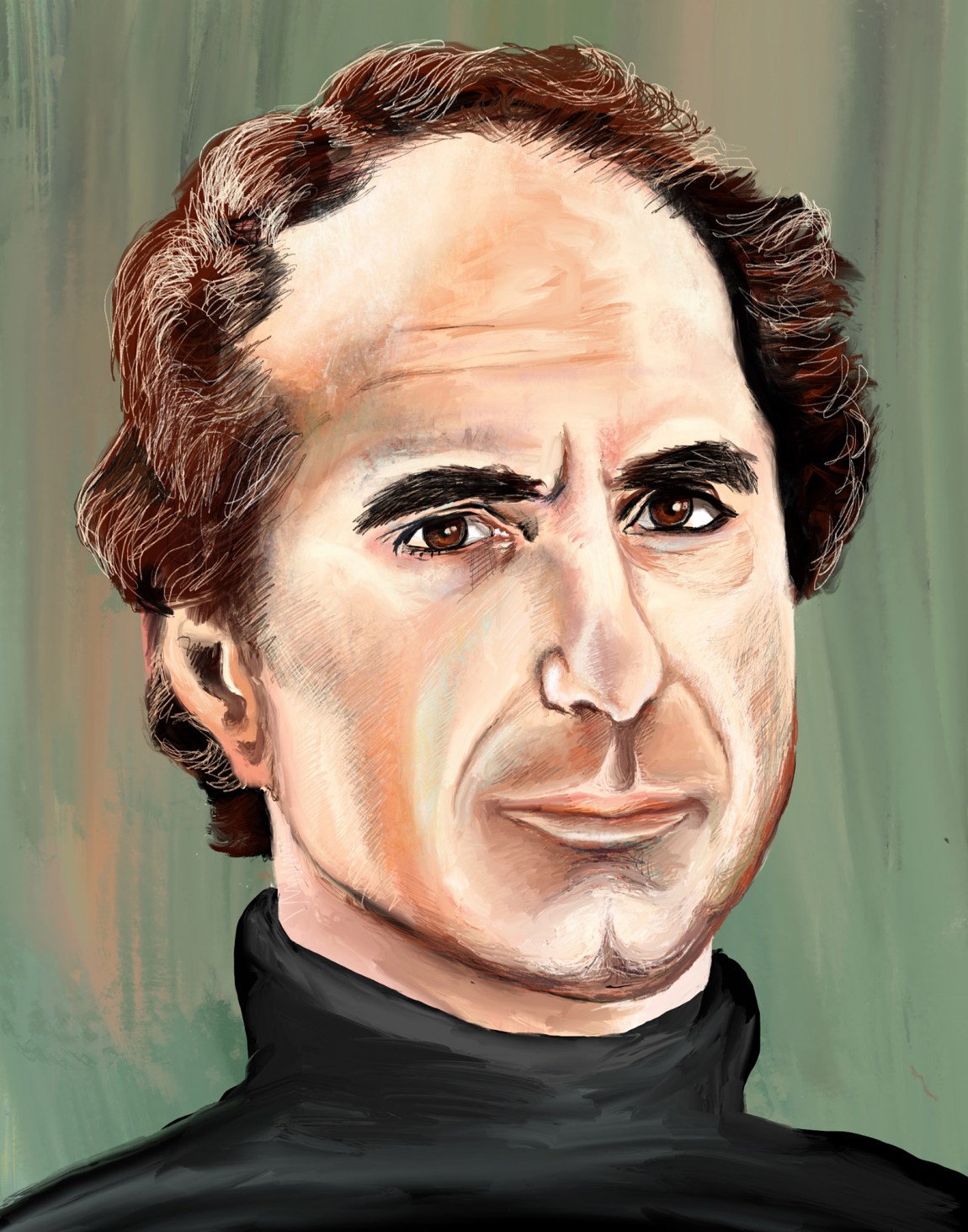

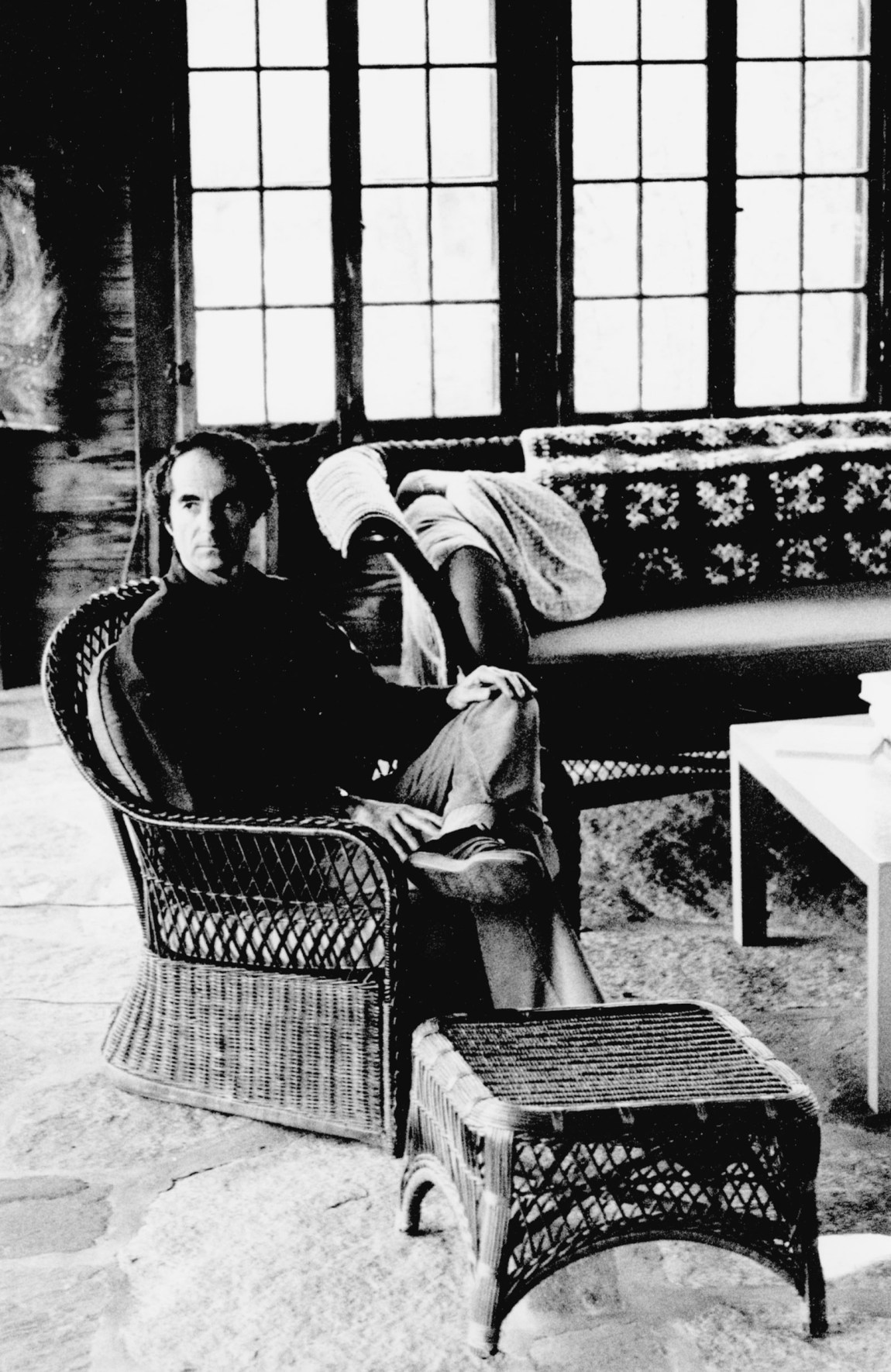

“I don’t want you to rehabilitate me. Just make me interesting.” Philip Roth died three years ago, on May 22, 2018, and those instructions to his biographer provide Blake Bailey with his epigraph. Yet how can we take him at his word? Roth believed the facts had to be set straight, the truth laid out, and the public disabused of what it thought it already knew. He wasn’t a self-hating Jew, as some of his first critics had argued, and unlike his character Nathan Zuckerman he hadn’t suffered a father’s deathbed curse or been cast out of the family for writing a scandalous best seller. He wasn’t as one with Portnoy, and people also needed to know that he wasn’t the monster of selfishness Bloom had described in her preemptive memoir, Leaving a Doll’s House (1996). He wasn’t his characters; nor was he the character he’d been made out to be. Ensuring that the record was straight meant, however, that he had to control the narrative, even though he also knew that human life was all about getting things wrong, and wrong again, and other people in particular.

Roth was eighty-five when he died, and had published his last novel, Nemesis, about a 1944 polio outbreak in his native Newark, in the fall of 2010. Two years later he let the news slip that he considered himself retired. There would be no new fiction, though he continued to supervise the ten-volume Library of America edition of his work, which appeared under the nominal editorship of Ross Miller, a University of Connecticut professor who had once been his friend. Yet Miller too was now one of those who needed to be put right. Roth had made him his biographer, but around the start of 2010 he took the job away, troubled by Miller’s failure to make much progress, to interview the older friends who had begun to die. What especially disturbed him, though, was the line of questioning Miller had begun to adopt. He found it traitorous in its sympathy for Bloom, and in retirement wrote several hundred pages of what he called “Notes on a Slander-Monger” in rebuttal. He also left a few hundred more of “Notes for My Biographer,” a point-by-point response to Bloom’s memoir. Neither manuscript has been published, and they now rest under a thirty-year embargo.

“Ross was no villain,” Benjamin Taylor writes in Here We Are, his fond and eloquent account of his friendship with the novelist, just an amateur, “someone handed a job for which he was ill-equipped.” Bailey does have that equipment, or most of it, and whatever one thinks about rehabilitation the interest isn’t in doubt. Still, he’s a curious figure for Roth to have authorized as a replacement. For as Roth himself asked at their first interview in 2012, why should a “gentile from Oklahoma” write his story, when his previous biographies had all been about WASP alcoholics? Bailey began his career with a life of Richard Yates, the author of Revolutionary Road (1961), and wrote another of the forgotten novelist Charles Jackson, whose Lost Weekend (1944) is now best recalled as the source for Billy Wilder’s Oscar-winning 1945 film.

What really attracted Roth’s interest, however, was Bailey’s 2009 biography of John Cheever, a book at once tactful and unsparing in its picture of that writer’s triumph and despair. Bailey drew skillfully upon interviews with Cheever’s friends and family, and then on his papers too, his confessional journal above all, and the result was as fluent a narrative as American biography can show. I don’t think the Roth book is as definitive. Nevertheless, it seems unassailable as to fact, withholding only the names of a few girlfriends; sympathetic in its use of those unpublished “Notes” but clear-eyed enough to allow for other judgments; and quickly moving despite its length, a coherent account of a major American life.

Which can’t be said for the Canadian academic Ira Nadel. His subtitle borrows from one of Roth’s greatest novels and in doing so implies something subversive, an alternative to any received or official version. Yet his reading of Roth’s life resembles Bailey’s, and though he offers a few more names and some otherwise unrecorded anecdotes, his handling of the narrative is awkward by comparison. Nadel writes that his organization is “thematic.” In practice that means he free-associates his way through Roth’s work and life in a way that isn’t only repetitive but also makes it hard to tell just what is happening when. He does, however, have a cameo appearance in Bailey’s pages. Roth sued him in 2010 over what he took as a misrepresentation of his personal life in an edited volume and was willing to pay more than $60,000 in legal fees to make him rewrite a passage. At the time Roth’s agent, Andrew Wylie, told Nadel that he wouldn’t get permission to quote from the novelist’s work in any future book, nor could he expect cooperation from his friends. Possibly that injunction was later lifted; in any case, Nadel does quote, and his acknowledgments thank a number of Roth’s friends, Taylor among them. No matter; I can’t imagine that many readers will choose his Philip Roth over Bailey’s.

Advertisement

That suit—which Nadel doesn’t mention—provides more evidence for Taylor’s judgment that the writer could never “get enough of getting even.” He seemed to court insult for the chance it gave him to fight back, and maybe that too showed a sense of self-sabotaging responsibility, only this time to what he saw as the truth. Margaret Williams had been too much for him. Even after five years of legal separation she refused to give him a divorce and hoped that his advance on Portnoy’s Complaint would make her own fortune too; he was freed only by her 1968 death in a Central Park car crash. “You’re dead,” he said to her casket at the funeral, “and I didn’t have to do it.” Nothing again would ever keep him from having the last word.

The three years since Roth’s own death would hardly seem long enough to research and write an eight-hundred-page biography, but Bailey’s interviews with some two hundred of the novelist’s friends, lovers, editors, and enemies—and especially with Roth himself—go back to 2012 (“Alfred Brendel, 7 July 2013”). Almost all of them were completed before the novelist died, and a few of those interviewed, like Alison Lurie, have since gone themselves. Bailey’s work relies on those conversations far more than it does on written documents, Roth’s manuscript “Notes” aside. There are relatively few quotations from letters here, though the ones that there are suggest that a volume of Roth’s correspondence will be worth having. There’s almost nothing from a journal or diary. He didn’t keep the kind of private record Cheever did; he had fewer secrets and was less introspective.

So the sense of character Bailey offers is above all a social one. This isn’t an oral history, but he does quote extensively from his interviews, and not just with Roth. We listen as the novelist’s friends think aloud and at times second-guess themselves, hear them describe his relation to them as much as theirs to him. In consequence these secondary figures become exceptionally vivid, and that ability to animate his minor characters seems to me Bailey’s most distinctive gift. In Cheever we got the separate voices of the man’s three children, who each had a different sense of him, and so it is here. Philip Roth comes as brightly peopled as a Victorian novel, with detailed portraits of its subject’s lovers, his college teachers at Bucknell, writer friends like Bernard Avishai and Judith Thurman, and the people who worked around the Litchfield County farmhouse that he bought in 1972, and where he spent most of his life’s second half.

Of course this kind of research yields other things too, and if you want to know who gave the nineteen-year-old Philip Roth his first blow job the answer is on page 78.

But isn’t that the problem? The problem not with biography itself so much as with this man’s biography? Because we want to know these things about him. Roth drew and smudged and drew again the line between life and art, and with every book it became harder to choose between them. He liked to complain that his reviewers thought he was the only novelist in America who never made anything up, but he also knew that the most effective lies stick as close to the truth as possible. Most of his characters have an immediate source in his own life, the women especially, and he had the necessary “splinter of ice in the heart,” as Graham Greene once put it, that allowed him to turn the people he loved into material. Himself too, and usually in far less flattering ways. But the particular things that happen to those characters aren’t always so immediately sourced, though here life itself might play him a trick. He once bared his chest to show an interviewer that he didn’t have a bypass scar, unlike his doppelgänger Zuckerman. Two years later he did, and joked that it was no good to him, he’d already used it.

I sometimes give my students a handout that defines the many differences between Roth and Zuckerman, between the real novelist and the fictional one, but really there’s only one that matters. Roth’s relations with his own parents remained warm, and he dedicated The Counterlife (1986) “to my father at eighty-five.” Zuckerman’s father, meanwhile, was supposed to have died in the early 1970s, right after calling his son a “bastard.” The writer stuck a thumb in the eye of his simple-minded critics, and yet in book after book he welcomed that simplicity, inviting the very reading he disdained. Catch me if you can, but he had already figured every angle, as if playing three-card monte with our minds. His whole oeuvre is a series of counterlives, alternate takes on the same material, like Rembrandt’s self-portraits or Monet’s waterlilies. And of course The Counterlife itself provides the best example: five versions of Zuckerman, and so loaded with irreconcilable details that each contradicts the others. None of them is entirely reliable, none the norm from which the others vary. So meaning itself becomes unstable: a book without a bottom, and sublime.

We’re fools to go on reading Roth’s work as if it were a disguised autobiography, and The Counterlife suggests a better way. The slippage between its different Zuckermans makes it seem a work of metafiction, but as we read each section it’s as real as fiction can be. Its dizzying effect depends, that is, on the writing—on Roth’s craft and art and skill, the things that most readers take for granted. Here are a few sentences from the opening pages of The Anatomy Lesson (1984), chosen almost at random. Zuckerman here suffers from a writer’s block in which the psychological and the physical are as one, and no doctor seems able to help. He wears a neck brace, there’s a “hot line of pain” running from his right ear to the middle of his back, and he’s treating himself with Valium and vodka. Sitting at the typewriter proves excruciating, but

writing manually was no better. Even in the good old days, pushing his left hand across the paper, he looked like some brave determined soul learning to use an artificial limb. Nor were the results that easy to decipher. Writing by hand was the clumsiest thing he did. He danced the rumba better than he wrote by hand. He held the pen too tight. He clenched his teeth and made agonized faces. He stuck his elbow out from his side as though beginning the breast stroke, then hooked his hand down and around from his forearm so as to form the letters from above rather than below.

None of these sentences is especially notable. They’re not like Saul Bellow’s—they don’t demand that we look at them, admire them. We look through them instead, look at the things they describe, the mock-heroic bathos of that “brave determined soul,” and then the visual precision of that stuck-out elbow. But look again and Roth’s little bits of repetition will start to catch, those four sentences beginning with “He,” three short and one long. We don’t notice the style and yet we do hear the voice, a distinction the novelist himself made in The Ghostwriter (1979), and what that voice has to give is a propulsive sense of rhythm and pace, the tick tick tock of the most purely readable prose in all American literature.

That’s one of Roth’s undersold strengths. Here’s another. Sabbath’s Theater opens with an account of the long adulterous affair between its title character and a Croatian immigrant named Drenka Balich, an affair that runs for better than a decade and ends only with her death. The next 385 pages in the Library of America edition cover just two days—two days in the novel’s present that also contain the entirety of the sixty-four-year-old Mickey Sabbath’s life. “Flashback” is too crude a word to describe what Roth does here. A moment unlocks a memory that unlocks another, allowing Sabbath to float back to childhood and then forward to Drenka’s deathbed, stopping along the way to sniff in a teenager’s underwear drawer and to remember—no, relive—another deathbed, when his actress first wife sat for three days beside her mother’s corpse, unwilling to release it to the undertaker.* Time moves and stands still, and we barely notice as one moment falls into another and the past becomes wholly present. Roth didn’t invent those moves. They go back to the early twentieth century, to Woolf and Proust among others. But he’s learned from every one of their experiments and does it with even more ease, a wholly naturalized and indeed invisible body of modernist technique.

Mickey Sabbath is a repellent character, and a great one, and the novel itself recalls Céline in its willingness to dive down, down, down, until we laugh at our own turning stomachs. Roth himself believed that two of the novel’s scenes were the best he’d ever written, and they do indeed demand superlatives. One of them puts Sabbath on the Jersey Shore, looking at his parents’ graves and then meeting his hundred-year-old cousin Fish, a man who lives alone and comes down the stairs but once each day to cook a lamb chop, and who thinks he remembers his wife. It’s Beckett but better—better because it’s set in the entirely recognizable social landscape of extreme old age. The other scene is harder, a memory within a memory, Sabbath’s recollection of visiting Drenka in the hospital just before she dies, one last time to talk, and laugh, and remember. Only what they remember is pissing on each other, the warmth and taste of a day of golden showers. I’d forgotten this moment entirely, and rereading it made me squirm, even as I knew their shared memory was itself a form of joy. And that’s when I thought of A Sentimental Education, in which on the last page Flaubert’s middle-aged characters recall an adolescent trip to a brothel and know that that “was the best time we ever had.”

Sabbath has always planned to kill himself—only to decide, in the novel’s last paragraph, that he can’t. “How could he leave? How could he go? Everything he hated was here.” Then Roth flipped the sentiment around: in American Pastoral (1997) Swede Levov looks out at his native land and thinks that “everything he loved was here.” Can’t have one without the other, I suppose, as a different Jersey boy once sang. The unruly and the responsible, Mickey and Swede, Dionysus and Apollo, even. Roth needed them both. Distrusted them too.

American Pastoral earned him an overdue Pulitzer. It should have been his second. In 1980 the judges had recommended the prize go to The Ghostwriter, but the Pulitzer board overruled them and instead gave it to Norman Mailer for the 1,100-page Executioner’s Song. Which of them has more weight now? Still, it took Roth a long time to find his feet, especially for someone who had already won the National Book Award, for Goodbye, Columbus, at the age of twenty-six. That had been his first book, with Portnoy’s Complaint a decade later, and The Ghostwriter ten years after that. Those are the only early ones that count. Some of the work in between has great moments—nobody forgets Kafka’s whore in The Professor of Desire (1977)—but there are also a few dogs, like the Nixon satire Our Gang (1971), and others that simply seem to mark time.

Roth needed to survive the fallout of his first marriage, he had to learn to live with the notoriety Portnoy’s Complaint brought him, and above all, as he said in a 1987 interview, he had to find the “confidence to take my instinct for comedy seriously, to let it contend with my earnest sobriety and finally take charge.” That comedy had been there from the start, but Roth spent years resisting his own best gift. Only when Nathan Zuckerman took hold in The Ghostwriter did he finally and irrevocably recognize just what kind of writer he was.

At that point Roth entered his long major phase, the almost unbroken string of successes that ran until The Plot Against America (2004) and Everyman. Just about everything in that quarter-century matters, and here Bailey’s one significant weakness as a biographer becomes apparent, one that marked the Cheever book as well. He’s not really a critic, and he isn’t that interested in the inner life of the fiction itself. I don’t expect him to offer a coherent reading of each book (Nadel provides a lot of plot summary, far more than we need), but I do wish he had more to say about the product of Roth’s long hours at that standing desk. How did his kind of fiction fit in with all the other kinds of American writing going on around him—the antic prose of Portnoy’s Complaint as set against that of the New Journalism? When did he realize that Zuckerman wasn’t a one-shot? The character made a brief appearance in My Life as a Man, but why did Roth decide to use him again, as The Ghostwriter’s first-person narrator, and when did he know that that book would require a sequel, and then another, only this time written in the third person? Or see that the aging Zuckerman would make a superb witness to other people’s troubles in American Pastoral and the two books that followed, now known collectively as the American Trilogy? What about his influence on younger writers?

And as I write this something else begins to nag, and the question Roth asked Bailey at their first interview starts to seem relevant. The drama of assimilation, the traditions of Jewish comedy and storytelling from which Roth’s own sense of performative outrage emerged: all that, and Newark too, seems muted here. It comes to us without the historical texture that marks Roth’s own account of the place, the layered sense of a milieu, at once sustaining and stifling, that marks even his most minor books. Maybe that’s unfair; still, there it is. Bailey has traced the novelist’s every relative and their medical records too, he’s defined the financial ups and downs of their immigrant history in America, but he doesn’t have the same grasp on this world that he does on the reticences of Cheever’s.

What he does superbly, in contrast, is chart Roth’s sexual and emotional life, and map its effects on his work. Some of this is straightforward. An English journalist with whom he had an affair while married to Bloom became the model for Maria in The Counterlife, and the haunted Faunia Farley in The Human Stain had a specific source as well. Almost all of Roth’s lovers have a place in his fiction, and most are remembered warmly, with the exception of the two he married. One thing that surprised me was just how conscientious a stepfather he was to Margaret Williams’s young children. He taught her daughter to read, and both she and her brother credit him with saving their lives; even Williams’s first husband speaks well of his influence.

But it didn’t work that way with Anna Steiger, Bloom’s daughter with the actor Rod Steiger. The novelist and the actress already knew each other slightly when they met up again in 1975, each of them now newly alone. Things then moved quickly, and they soon decided to split their time between Roth’s farmhouse and Bloom’s own home in London. Steiger was sixteen when the two began living together, and she proved hostile from the start.

Or maybe Roth was. He told one story, Bloom and Steiger told different ones—a family drama in which there’s no such thing as truth, only mine and yours and yours. What seems clear is that Steiger believed her mother had abandoned her and resented Roth’s very existence; Bloom in turn craved her daughter’s approval and treated her as one whose every need must be met. The novelist saw the intensity of the relationship between mother and daughter as a threat to his peace and refused to let the young woman live with them; she should instead get student housing at the London conservatory where she was enrolled. Bloom thought he was cruel and unyielding, everyone acted badly, and it went on for a long time.

Later there were other problems. According to Taylor, Bloom felt that some of Roth’s medical ills were imaginary; and Bailey describes how, at moments of crisis, she would break, before witnesses, into great sobs of self-pity. But she got her damning version into print first, and Roth thought the bad publicity had cost him the Nobel Prize. Other more personally monstrous figures were luckier, with their full stories emerging only after Sweden had called; think of Derek Walcott or V.S. Naipaul.

Some readers will wish Bailey were harder on his subject, more openly judgmental, and another biographer will one day write a more prosecutorial book. Certainly there’s a bill to draw. Roth was vindictive, and not just toward Bloom; The Human Stain (2000) is marred by its caricature of an academic feminist, the kind of reader he felt was determined to misunderstand him. He dropped editors and friends who no longer seemed useful, and he was compulsively unfaithful. After the end of his second marriage he had a series of short-lived affairs with ever-younger women. Bailey writes that he “enjoyed playing Pygmalion,” and he treated his girlfriends generously, too generously; a gift to one of them of $100,000 made me feel queasy, as though the check itself said “stick around.” But eventually sex was over, even for Philip Roth, and really around the time he stopped writing fiction. His last years were surprisingly peaceful, despite his enduring physical pain. He read deeply in American history; he renewed his friendship with some of his old loves, and their companionship helped ease his body’s passage.

One who didn’t come back was Maxine Groffsky, the daughter of a New Jersey glass distributor whom Roth had used as the model for Brenda Patimkin in the long title story of Goodbye, Columbus. After graduating from Barnard she worked for The Paris Review, running the quarterly’s office in the French capital, and later became a literary agent in New York; a Lee Friedlander portrait from 1972 shows a woman of formidable intelligence and chic alike. Few of Roth’s lovers refused to speak to Bailey; she did, in a letter he calls “cordial but firm.” Groffsky’s family, Bailey writes, seems to have believed that “Goodbye, Columbus” had “blackened” their hometown reputation, and twenty-five years later her younger sister came up to Roth after a lecture and laid into him, claiming that the book had destroyed her family’s life.

Just what details had hurt the most went unsaid. Brenda’s diaphragm, one of the first times that birth control had provided a plot point in American fiction? The virtual illiteracy of the Patimkin father, or the dopey, basketball-playing big brother? That unforgettable refrigerator full of fruit? After I had almost finished this piece I went back, on a February morning, to read “Goodbye, Columbus” for the first time in almost forty years. It hadn’t been my first Roth—that was The Ghostwriter—but I had gone on to it immediately, and what I remember from that initial reading is simply how hard some pages had me laughing. Now I was laughing again. There were earnest moments, sure, but the young Roth had trusted his comedy. He didn’t yet have anything to live up to, no prizes behind him or burden of expectations, and at the time he didn’t see it as a major work. It was the longest thing he’d yet written, but still, it wasn’t a novel; later he spoke of it as a “kid’s book” and wished people would forget about it.

It’s true that its characters are only half-realized. Nevertheless, Roth’s entire future is there. The subject matter first, Newark and sex and Jews, money, success, and the generation-by-generation movement out into American life. Then that fresh and flexible voice, the speaking voice above all, as one hears it in the monologue Brenda’s traveling salesman uncle delivers near the end of the book, the story of his life selling light bulbs and of a girl he once met who believed in “oral love.” And beyond that the ambivalence. The narrator, Neil Klugman, doesn’t like the fact that Brenda has had a diamond-shaped bump on her nose removed, but then she’s right too in seeing him as slightly nasty.

There’s more, though. At one point Neil drops some papers off at Patimkin Sink, the Newark factory where Brenda’s father has made his fortune, and in seeing him there Neil recognizes “the satisfaction and surprise he felt about the life he had managed to build for himself and his family.” Ben Patimkin has left the old neighborhood behind and moved out to Short Hills. What’s more, he’s sent his daughter to Radcliffe, and at this point it isn’t Neil but the novel itself that’s on the man’s side. In business, he tells the boy, “you need a little of the gonif in you. You know what that means?” Neil does—a point in his favor. The Patimkin kids don’t; in fact they might as well be “goyim, my kids, that’s how much they understand.” But that’s the point, and it makes the man proud. They don’t need to know, and yet Roth himself would always remember what a gonif was. It was where he came from, and like all great novelists he was a bit of one as well, stealing other people’s lives and fixing them on paper.

I thought of something else as I read, too. I thought of the very last words of American Pastoral. We’re a generation on and the money has gotten easier in its shoes, but the hard work remains; you may no longer live over the shop, but you mind it all the same. The Patimkins’ suburban house has become Swede Levov’s gentleman’s farm, a place now threatened by the discord of our national life, an “American berserk” that condemns and rejects the striving, sober comfort in which his family has its being. And yet, “what is wrong with their life? What on earth is less reprehensible than the life of the Levovs?” The good son asked such a question in book after book, and the man who made Mickey Sabbath always answered it with another one. Isn’t that the problem?

- Roth took the incident from Bloom’s behavior at her own mother’s death. Unforgivable, and on the page unforgettable.