In 1963 thirty-four-year-old Louise Fitzhugh was fresh off a successful exhibition of her paintings and drawings at an Upper East Side gallery when she suddenly declared her fine art career a catastrophe. She’d recently illustrated the children’s book Suzuki Beane, a charming Beatnik spin on Eloise, written by her friend and sometime lover Sandra Scoppettone, and it was to children’s literature that Louise turned again. She wrote to her lifelong friend the poet James Merrill to tell him about her new book project: “It is called Harriet the Spy and is about a nasty little girl who keeps a notebook on all her friends.”

Published in 1964, Harriet the Spy was an instant classic, selling 2.5 million copies in its first five years. It tells the story of eleven-year-old Harriet M. Welsch, who lives in a townhouse on East 87th Street and attends the tony Gregory School (based on the Dalton School). Her days are spent roaming the neighborhood, spying on friends and other local characters, and recording her observations—from the sweetly unsophisticated to the downright cruel—in her notebook. Harriet is a tomboy who dresses in jeans and a tool belt, a writer keen to use her voice no matter what it might cost her. She broke into the popular imagination alongside Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, and Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones. “I’ll be damned if I’ll go to dancing school,” Harriet screams at her parents at dinner, emboldened to resist by her feelings of solidarity with her friend Janie, a miniature mad scientist. “Don’t give up,” Harriet whispers as Janie prepares to be scolded by her father. “Never,” Janie whispers back.

Despite its popularity, Harriet the Spy nevertheless drew critical ire and moral panic. Some critics worried over the “horrid example” that Harriet set, calling the novel “depressing” and “pathetic.” In 1965, writing in The Horn Book, an influential journal devoted to children’s literature, Ruth Hill Viguers attacked the novel for its “cynicism” and cried, “This is a very jaded view on which to open children’s windows.” Even the novel’s champions highlighted its bitter-pill quality: Janet Adam Smith, writing in these pages, celebrated Harriet as “splendidly sour.” Smith continued, “As I love a tiger behind bars, I love Harriet so long as she is caged in a book.” Harriet was as unsettling as she was magnetic, and the novel ends on the dangerous acknowledgment to children that “sometimes you have to lie.”

Surprisingly for an author whose work courted controversy, details about Fitzhugh’s life have until recently been hard to come by. Leslie Brody, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Redlands, had her work cut out in writing Fitzhugh’s biography. The Fitzhugh estate—administered until 2009 by Lois Morehead, Fitzhugh’s partner at the time of her death—is, as Brody puts it, “protective of information regarding Louise’s life.” Both Brody and Fitzhugh’s first biographer, the academic Virginia L. Wolf, have speculated that the estate’s stance is related to a broader desire among those who knew and worked with Louise to maintain a distance between Fitzhugh the complicated bohemian lesbian and Fitzhugh the celebrated children’s book author.

Sometimes You Have to Lie is a fun, gossipy biography. Fitzhugh seems to have known everyone in downtown New York in the 1950s and 1960s, from high to low, from poets to playwrights to soap opera actresses. In her early twenties Fitzhugh dated France Burke, the daughter of the midcentury literary titan Kenneth Burke, and spent summers at the Burke family compound in rural New Jersey, hobnobbing with avant-garde writers and artists like Djuna Barnes and Berenice Abbott. In her thirties she struck up a friendship with Lorraine Hansberry. The biography is full of dinner parties and gallery openings and galloping jaunts between New York City, the Hamptons, and Litchfield County, Connecticut.

But Fitzhugh herself left few personal papers: she didn’t write a lot of letters, and the small number of journals she kept continue to be held closely by the estate. The stories that Brody is able to tell the reader, then, are mostly second- or third-hand, conveyed to her by friends as they reminisced after Fitzhugh’s death or by the handful of enterprising earlier writers who attempted to crack the nut of Fitzhugh’s life in the 1990s, notably Wolf and the journalist Karen Cook. Everyone seems, like Harriet M. Welsch, to be consulting the notebooks they kept on Fitzhugh as they lived alongside her. But as any sensitive reader of Harriet the Spy knows, spying on others is not really about getting to know them. It’s about getting to know yourself.

Advertisement

Louise Fitzhugh was born in 1928 in Memphis, Tennessee, where she was brought up in great wealth amid a dysfunctional family who would have been at home in a Southern Gothic novel. Her millionaire father, Millsaps, left her middle-class, dance instructor mother, Mary Louise, when Louise was a baby. The subsequent divorce and custody battle was a salacious public event that unfolded for years and was covered breathlessly in the Memphis press. When Louise was two and a half, full custody was awarded to her father. She was then told that her mother was “in heaven,” a lie that held until she was six and Millsaps began to allow her mother infrequent visits.

As a child Louise knew that her family situation was chaotic and precarious, but it wasn’t until she worked in the local newspaper office archives the summer before heading to Bard College that she discovered the truth of her early childhood through the paper’s coverage of the divorce. At that point, she was already in her first serious lesbian relationship and was clear about her desire to leave behind the boozy, glad-handing social world of upper-crust white Memphis.

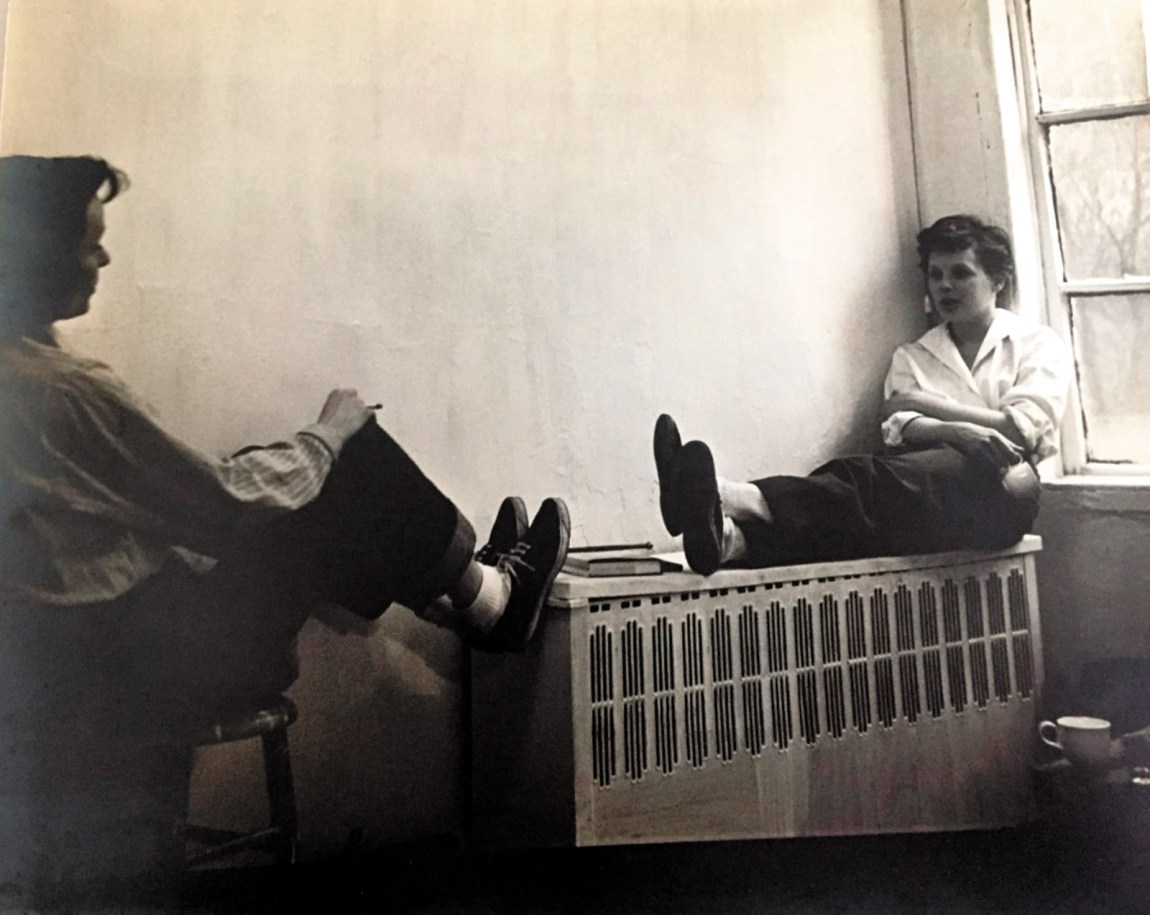

After receiving an inheritance from her grandmother, and six months shy of graduating from Bard, Fitzhugh moved to East 17th Street and started hanging out in Greenwich Village and making a name for herself as a painter and illustrator. She was very petite, generally kept her hair short, and wore tailored men’s clothing. The writer M.J. Meaker, Fitzhugh’s friend and the progenitor of lesbian pulp fiction (Meaker also wrote acclaimed young adult fiction under the name M.E. Kerr) said of her, “She was like a wonderful-looking little Victorian boy, running around in her boots and suits.” Unlike many of her friends, Louise did not lead a double life. Meaker added, “Louise was always herself, never in the closet.” Her long-term girlfriend Alixe Gordin reminisced about falling in love with Fitzhugh’s beautiful legs and wonderful laugh, the two of them harmonizing on folk songs together in their floor-through brownstone apartment near 14th Street in the late 1950s.

But being out in her personal life did not mean that she was out professionally. Part of perhaps the last generation of writers able to forgo the performance of self, Fitzhugh was publicity shy. The publicity that did exist for her books tended to cast her in a childish light—her author photo for Harriet the Spy depicts the thirty-something woman sitting on a swing in a playground. After her untimely death in 1974 of an aneurysm (she was forty-six), her image was straight-washed; her obituary described her as single, though she had been partnered with Morehead, and many of her friends believed that outing her would harm her legacy. Their endeavors were so successful that in the 1990s critics started “recovering” her queerness, a curious phenomenon given that Fitzhugh had lived her life quite out a mere twenty years before.

It’s strange to have to recover what should be common knowledge, but the queer history of mid-twentieth-century children’s literature is still being written. Fitzhugh was published by the famed children’s book editor Ursula Nordstrom, who was a lesbian and who published work by Margaret Wise Brown, Maurice Sendak, and Arnold Lobel, all of whom were gay or bisexual. Even without knowing anything about the author’s sexual identity, queer children (and adults!) have long drawn comfort from Harriet the Spy, which, like Lobel’s Frog and Toad series, contains undeniably queer subtexts.

The scholar Robin Bernstein identifies Harriet the Spy’s queerness in its formal elements: its meandering structure, its giddy unpleasantness, its commitment to growth without change. Harriet the Spy is not queer because its author was, or because of anything to do with the identity of its child protagonist. It’s queer in its very bones. Harriet writes down her reason for spying early on:

OLE GOLLY SAYS THERE IS AS MANY WAYS TO LIVE AS THERE ARE PEOPLE ON THE EARTH AND I SHOULDN’T GO ROUND WITH BLINDERS BUT SHOULD SEE EVERY WAY I CAN. THEN I’LL KNOW WHAT WAY I WANT TO LIVE AND NOT JUST LIVE LIKE MY FAMILY.

Harriet the Spy is populated by a cast of fascinatingly demoralizing characters we check in on as Harriet follows her “spy route” around the neighborhood every day after school—from her best friend, Sport, who has been left to fend for himself by his alcoholic novelist father, to Harrison Withers, a gentle man who happily shares his small apartment with twenty-six cats (many named after Fitzhugh’s friends) until the Health Department intrudes. There are the bourgeois mothers, always screaming their observations at their children, and the divorcée Mrs. Agatha K. Plumber, who has discovered the secret of life (“to stay in bed”), and a sort of intergenerational soap opera taking place daily at the Dei Santis’ grocery. Harriet bundles herself into a dumb waiter, suspends herself above a skylight, and claws up to windowsills in order to peer at these people, going unseen and unnoticed herself.

Advertisement

The picaresque literary structure of the novel develops as we get revelatory glimpses into the kinds of things that Harriet has been writing in her notebook about her friends and classmates:

NOTES ON WHAT CARRIE ANDREWS THINKS OF MARION HAWTHORNE

THINKS: IS MEAN

IS ROTTEN IN MATH

HAS FUNNY KNEES

IS A PIG

The spiteful observations continue, but the novel never casts them as anything other than what they are: imperfect attempts on the part of a child at developing self-knowledge. Things start to fall apart for Harriet when she sustains two major blows to her stability: her beloved nanny Ole Golly abruptly leaves (she plans to get married and move to Canada), and then, nightmarishly, in the confusion of playing tag in the park, Harriet’s notebook falls into the hands of the friends she loves yet skewers in writing. Janie calls Sport over and reads a passage from the notebook aloud to him, right in front of Harriet: “SOMETIMES I CAN’T STAND SPORT. WITH HIS WORRYING ALL THE TIME AND FUSSING OVER HIS FATHER, SOMETIMES HE’S LIKE A LITTLE OLD WOMAN.”

Harriet’s response to having her worst self revealed is to double down. She keeps writing. Her friends try to form “The Spy Catcher Club” to turn the tables on her, but it’s easy to see that they lack the writerly drive to sustain such a gambit. In her notebook Harriet brainstorms the meanest things she could say or do to each of them (“RACHEL HENNESSEY: HER FATHER. ASK HER WHERE HE WENT”). The final third of the novel is outrageous. Harriet gets sent to a psychiatrist; her parents try to take her notebook away from her. But nothing settles Harriet’s roiling soul until Ole Golly at last writes her a letter with some uncomfortably accurate advice: “You are going to have to do two things, and you don’t like either one of them: 1) You have to apologize. 2) You have to lie.” And from there, Harriet is launched, finally, toward the world of adult sociality and all of its compromising falseness.

Yet the best thing about Harriet the Spy is how Harriet’s character remains fundamentally unchanged from start to finish. Instead of transforming herself, she simply has to learn how to misdirect others so she can keep doing all the awful stuff she enjoys. What a relief to encounter this as a child, subject as children are to a near constant barrage of messages telling them to be otherwise. Brody’s account of the novel relies heavily on generational analysis; she sees Harriet the Spy as a prototypical Baby Boomer text, a “countercultural” story that questions authority, and she—like many other critics—presents the novel instrumentally, as a tool that readers can use to do something else with (“rethink society” or the like). But Harriet the Spy also works as an antidote to these utilitarian values, as well-intentioned as they may be. In the end, Harriet concludes, “Some people are one way and some people are another and that’s that.” The novel feels less like an attempt to do something than a document of survival.

In 1965 Fitzhugh published a follow-up to Harriet the Spy titled The Long Secret, which finds Harriet and her friend Beth Ellen summering in the Hamptons. Sweet, quiet, blond Beth Ellen was a minor character in the earlier novel but takes center stage here. The Long Secret opens on a mystery involving notes that appear all over town, saying things like “JESUS HATES YOU.” It ends with the revelation of Beth Ellen’s frighteningly bottled-up rage at her parents, a hard-drinking, Gatsby-esque pair (clearly fictionalized versions of Fitzhugh’s own parents) who have suddenly reappeared in Beth Ellen’s life, after having left her for years in the care of her grandmother. Along the way, Beth Ellen gets her period, making The Long Secret what many critics agree is the first literary representation of menstruation in a text aimed at young readers. (Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret was published five years later.)

The Long Secret is a fascinating novel that has suffered from comparison to Harriet the Spy. Its contemporaneous reviewers dwelled on whether Beth Ellen was “as interesting” as Harriet, whether the new novel was “as good” as the last. But The Long Secret is its own thing. In it, Fitzhugh further hones her use of epistolary elements, incorporating notes, letters, and other textual detritus into the story. Fitzhugh’s attraction to this technique recalls a point once made by the queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, who argued (of gothic novels) that the inclusion of illegible manuscripts, letters, and framed narratives in fiction serves to emphasize “the difficulty [a] story has in getting itself told.”

Though Harriet the Spy and The Long Secret are hardly gothic novels, they share this resistance to straightforward telling. In each, Fitzhugh presses on both the power and limitations of language by chronicling the experience of young girls who can’t figure out how to communicate their inner life. When Harriet, obtuse about her friend’s emotional crisis, prattles at Beth Ellen in The Long Secret, the narrator reveals: “Beth Ellen thought it totally immaterial what Harriet knew or did not know, but she wasn’t sure how to say this. She looked, therefore, at her foot.”

After The Long Secret, Fitzhugh veered in different artistic directions. She got together and broke up with a variety of women, finally settling down with Lois Morehead in Connecticut in 1969. She ended her editorial relationship with Ursula Nordstrom and Charlotte Zolotow after they agreed to publish but, Fitzhugh believed, failed to fully support the truly weird picture book she created with Sandra Scoppettone titled Bang Bang You’re Dead (1969), an antiwar book featuring two armies of goblin-like children whose play-fighting turns real. (Representative text from the book: “There were screams, yells, blood, and pain. It was awful.”) She returned to painting and illustration, now from the comfort of the beautiful attic studio at her house in Bridgewater, Connecticut. And she began work on her final novel, Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change (1974).

Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change tells the story of the Sheridans, an upper-middle-class Black family living on the Upper East Side. Emma (short for Emancipation) is eleven, attends the same fictional private school that Harriet and her friends do (though years later), and aspires to be a lawyer. Her younger brother, Willie, wants to be a tap dancer. Their father—a staid district attorney—opposes both of their dreams, which flout his desires for respectability: a profession for Willie, wife- and motherhood for Emma. Their mother struggles to ease the tension in the household, and they all live unhappily together for the first third of the novel until, in a bizarre twist, Emma hooks up with an underground group of children’s rights activists: a set of loosely organized, co-ed, and multi-racial neighborhood “brigades” that make up what they call a “Children’s Army.” One meeting begins with a moment of silence held for Clifford Glover and Claude Reese (both real child victims killed by police in the 1970s). The rest of the novel alternates between the claustrophobic bourgeois home and scenes of complex political organizing undertaken by children explicitly engaged in consciousness-raising.

Brody—working with interviews given by various friends of Fitzhugh’s—links her death on November 19, 1974, to the middling reviews that Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change received that fall. The evidence feels thin: Brody emphasizes the effect that a single Publisher’s Weekly review had on Fitzhugh’s final week. It seems Fitzhugh had been drinking heavily, and M.J. Meaker claimed that Fitzhugh told her it was “because of the review.” Whether or not there was a causal relationship, it’s true that Fitzhugh was disappointed by the reception of much of her work for children by the adults who made literary judgments.

Reading the novel today, the children’s organizing plot feels fresh and radical, and Emma’s consciousness raw and real. Lizzie Skurnick, the founder of Lizzie Skurnick Books, reissued the novel in 2016, after it had gone out of print. (The estate did not fight her as it had Scoppettone when she attempted to reprint Suzuki Beane. “Nobody cares about that novel,” Skurnick told me wryly.) When researching cover art for the reprint, Skurnick had to page through thousands of stock images to find one of a nerdy Black girl with glasses to represent Emma, and remarked admiringly on Fitzhugh’s drive to write from the perspective of a type of character still rarely represented in children’s literature. Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change is, like all of Fitzhugh’s work, about liberation and the children seeking it: liberation from traditional social expectations about gender, race, sexuality, and from the extreme pressure adults often don’t realize they are applying.

At her death, Fitzhugh left a number of unfinished manuscripts, some of which were tidied up and published posthumously (like Sport and I Am Five), while others (some unfinished picture books, a play titled Mother Sweet, Father Sweet, and Crazybaby, a novel for adults) were left in an archive that remains private. Most of Fitzhugh’s fine art is privately held. The full story of her life and work, it seems, has had some trouble getting told. Alixe Gordin suggested to Brody that, after Fitzhugh’s death, Morehead “choreographed a spectacle meant to enshrine a commercially viable Louise Fitzhugh…a chaste spinster lady with a good sense of humor.”

Sometimes You Have to Lie is a valuable corrective to this invention. After I finished it, I felt like I knew Fitzhugh better, could hear her voice more clearly, and was afforded new insight into her fiction. But there’s a part of me that still holds onto something far deeper that is dramatized in Fitzhugh’s fiction—that nobody owes themselves to anyone, least of all Fitzhugh to us. At the end of Nobody’s Family Is Going to Change, Emma has a revelation. Sitting together with her girlfriends, trying to organize themselves in defense of themselves, they start talking about their families:

“Your father,” said Saunders, “is a lost cause. He thinks those boys are great and he’s never going to think you’re anything, because you’re a girl.”

“Well,” said Goldin, “I can’t change that.”

“No, but you can stop wanting him to change,” said Saunders.

Emma felt like the top of her head would fly off. Saunders got it, the whole thing. “That’s what I mean,” said Emma loudly. “That’s just what I’m talking about. We have to stop waiting around for them to love us!”

This Issue

May 13, 2021