Susan Taubes’s novel Divorcing begins with the death of its main character. Sophie Blind wakes up in an apartment by the Hudson River, still groggy from a dream, or perhaps still dreaming, to find her lover bending over her, saying, “you’re dead Sophie.” Then she remembers:

I died on a Tuesday afternoon, struck by a car….

The sensation of my head severed from my back is still vivid. My body growing enormous, its thousands of trillions of cells suddenly set free, spread, speeded, pressed jubilant.

It’s a vision of death that holds terror and freedom at once: the body enlarged rather than destroyed, its cells liberated. “Spread, speeded, pressed”: even the sibilance suggests a vaulting song.

Given that Sophie is in the midst of ending her marriage, this dream of death suggests itself as a metaphor for divorce: the death of an old self suddenly confronting the vertigo of freedom. And given the biography of Sophie’s creator, it feels less like metaphor and more like warning. Only a few days after Divorcing was published, in November 1969, Taubes committed suicide by drowning herself in the Atlantic. It’s hard not to read much of the novel as an extended suicide note. “Now that I’m dead,” Sophie jokes with her lover, “I can write my autobiography at last.”

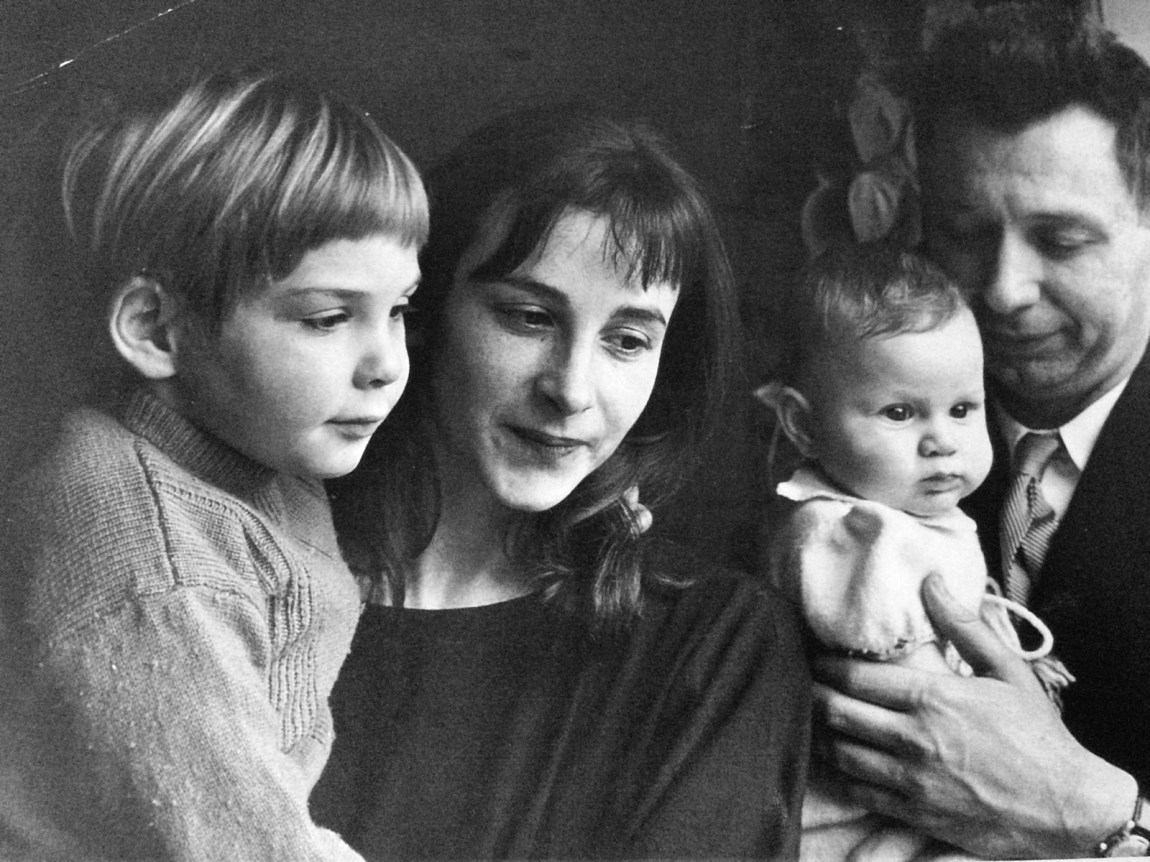

Although her suicide happened soon after her novel’s publication—and even sooner after a devastating review in The New York Times, a timeline that invites causal speculation—Taubes had in fact been planning it for some time; she had struggled with depression for years. She was forty-one when she died, her son sixteen, her daughter twelve. Her body was identified by Susan Sontag, one of her closest friends. Years later, Sontag told her own son, David Rieff, “I will never forgive her…and never recover from what she did.”

In the half-century since her death, Taubes has mostly fallen into obscurity—her novel largely forgotten, her life remembered mainly through other lives: confidante of Sontag, ex-wife of the charismatic philosopher and professor Jacob Taubes, daughter of the renowned Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Feldmann, granddaughter of the Grand Rabbi of Budapest. Taubes and Sontag met in the 1950s, when Sontag was still married to the sociologist Philip Rieff, and both couples lived in Cambridge. Sontag’s diary suggests that she slept with Jacob at least once, but her deeper connection was to Susan. The women remained close after their respective divorces. Sontag would visit Taubes’s Manhattan apartment to find it full of rotting food. “Same name as me, ma sosie [my double],” Sontag once wrote of Taubes, “also unassimilable.” As Sontag’s biographer Benjamin Moser wrote, “unassimilable” was “the word [Sontag] reserved for people, including her [long-dead] father…who were impossible to know or understand.”

Divorcing is a strangely provocative and unsettling work of art—a quilt of memories, dreams, arguments, trysts, snippets of motherhood, and dark fantasies, including an autopsy, a funeral, and a trial. The novel moves across national borders—her working title was To America and Back in a Coffin—and zigzags constantly between gruesome daydreams and mundane daily life. The thresholds that obsess it most are death and divorce, the latter as a kind of death-in-life. Both dangle the prospect of simultaneous anguish and liberation; both illuminate Sophie’s desire for self-possession. It begins to feel like travel, sex, fantasy, divorce, and death are all handmaidens of the same siren call—to keep changing at all costs. As if Sophie and Taubes herself both embodied Sontag’s pronouncement that “I am only interested in people engaged in a project of self-transformation.”

Imagining her own wake, Sophie pictures staring up from her coffin and watching her “bereaved husband…waltz[ing] through the crowd on waves of sympathy.” And then—frustrated by the fact that her husband has had her corpse made up to be the spitting image of herself as a young bride, yet another way in which he tries to keep her trapped inside an ideal—she imagines a more final escape: “When I’m truly dead, my friends, I won’t see you standing around me. I will find a way out, I’ll get back my arms and limbs, my head, even my heart, I’ll find it whatever you’ve done with it.”

I am a “child of divorce,” as they say, as if divorce itself were a parent. When I was young, I believed that divorce involved a ceremony, the inverse of marriage, in which the married couple moved backward through the choreography of their wedding: starting at the altar, unclasping their hands, and walking separately down the aisle. Once I asked a family friend who came to dinner, “Did you have a nice divorce?” Perhaps it seemed natural to me that every meaningful transition, however painful, deserved a ceremony. In retrospect, I like how the ritual, at least as I wrongly imagined it, summoned the idea of a processional, the possibility of moving toward something, a different life or a different self. My naiveté recognized something I still believe: that endings shape us as much as beginnings do.

Advertisement

Years after my parents’ divorce, once I’d become a mother myself, my mother told me about an argument she’d had with my father near the end of their marriage. She told him, “You don’t know me at all! You don’t even know that I might want to become a priest.” At that point, my mom had been working in public health for nearly two decades, and this argument was the first time she’d ever articulated—to herself, to anyone—that she felt a calling to the clergy. A decade later she became an Episcopal deacon. It was fascinating to me that she discovered that part of herself through the act of argument. By saying to a partner, This is what you were never able to see in me, you might be able to see some buried part of yourself more clearly, or for the very first time.

As a little girl I loved writing fairy tales without happy endings: the dragon ended up incinerating everyone, or the princess left her prince standing at the altar and ran away to fly over the sea in a hot air balloon (which maybe was a happy ending, just a different kind). And though I’ve always loved to recount that version of myself, the little girl open to dark conclusions, in truth I was also the child pausing in supermarket aisles to look at bridal magazines, glossy pages full of sweetheart necklines and endless trains like crystal spiderwebs. Both of these little girls became part of me: one wanted a lace-draped, perfume-scented perfect day, the other to shatter that dream, to see the princess run away.

The traditional marriage plot of nineteenth-century realist novels followed the tangled trajectory of courtship to culminate in the emotional and financial consolidation of a wedding. Divorcing presents us with the opposite: a plot that explores the simultaneous grief and freedom that rise from a union splitting along its central seam. In this inverted conversion narrative, the subject of the divorce plot loses faith rather than finding it—and from that loss of faith comes a multitude of forking paths: grief, abjection, wanderlust, full-stop lust, sexual renaissance, prodigal motherhood.

Published two years after Taubes’s own divorce was finalized, Divorcing tells the story of Ezra and Sophie Blind, who bear no small resemblance to Jacob and Susan Taubes. Near the beginning of the novel, Ezra arrives one night at the Paris apartment where Sophie is living with their children—Ezra is teaching in the US, Sophie has asked to live apart—and Sophie tells him in the kitchen that she wants their marriage to end. “One is never prepared for the queer, horrible way these things really happen,” Sophie reflects. “It’s unbearable.” It’s a hundred more pages before the novel offers an account of their courtship, compressed with thrilling economy. Taubes whittles the expansive terrain of the marriage plot into a single paragraph:

The marriage of Sophie Landsmann to Ezra Blind, the young rabbi and visiting scholar from Vienna, who had singled her out at a lecture, in its way as mysterious as her grandmother’s: two people, practically strangers entering upon a life commitment without any romance and the usual preliminaries of courtship, without so much as a dinner, a movie date, without a word of endearment having been spoken, or any kind of intimacy between them; oddly impersonal, formal, totally unsentimental and yet curiously free and comfortable with each other; a marriage that happened on the basis of a sermon he delivered to her alone on the evening they met and the next evening when she answered his marriage proposal by asking him to deflower her, the sermon and the proposal repeated for the next six weeks, always the same sermon delivered by the young rabbi from Vienna to the psychoanalyst’s daughter who argued against God and marriage, till the night she could not answer him: she wanted only to feel simple and comfortable like the night he deflowered her, she wanted all her life to be simple like that; and they became engaged.

This is a different version not only of narrative structure but of romantic attachment: no dinners, no movies, no terms of endearment; a dynamic that’s simultaneously “impersonal” and “curiously free.” Sophie is a young woman who wants to lose her virginity more urgently than she wants to be married, who in fact “argue[s] against God and marriage” until she finally relents. Her decision to accept Ezra’s proposal is simply one staging of an ongoing conflict between her independent will and the powerful social structures that make her feel most “simple and comfortable” when she shapes her desires around the desires of a man.

Advertisement

As a character, Sophie is fluid and gleaming, sly and seductive. She asks for an extension of her honeymoon in place of a fur coat; she carries “her accumulation of some thirty-five years in boxes, suitcases, trunks, barrels, crates and the like” as she moves around the world, and is “cheerfully resigned” to losing things. She fixes lunch for her kids as she imagines a divorce hearing full of dead ancestors, the trial of Blind vs. Blind, in which Sophie cries out to those convened—the judge, the jury, the lawyers, her husband, and her father: “I’m sick of all this fuss. Go ahead, you dodoes, and condemn me for eating fried octopus, cock sucking, animal worship…. I confess to all your charges.”

These pages are full of affairs that veer between unsentimental detachment and impulsive romance, refusing to resolve into any consistent emotional register. After one tryst with a married businessman from Milan, Sophie fills her bag with hotel stationery and soap; no tear-stained diary entries here. At other moments, she loves the swooping plotlines of grand gestures and cosmic alignment, flying to New York to see her lover Ivan after dreaming about sucking a rabbit bone to its marrow on his Manhattan balcony. Amid these affairs, Sophie is also a mom splashing around in the bathtub with her three children, giving them beads and clay and rags and paint to play with, defending them from their father’s scorekeeping and manipulations.

By dramatizing the messy intersections between Sophie’s life as a mother and her life as a lover, Divorcing collapses the madonna–whore dichotomy. In her Paris kitchen, Sophie’s children cluster around her, eager for her attention, wondering, “Who sent her that fat letter from New York she is reading while the spaghetti boils?” When she stands in the apartment of the lover who sent the letter, she is vulnerable and exposed: “The fact is that she has never been as simply herself as now, wrapped in Ivan’s towel. But it’s terrifying to be this naked, to have given up all personhood…. This nakedness, she knows, can never again be clothed.” But rather than promising to expose Sophie’s naked psyche, Taubes’s novel explodes the idea that its heroine has a coherent, single self—that the psyche can be stripped like a naked body, as many men have tried to do to Sophie, by analyzing her or fucking her or marrying her.

Sophie remembers her wedding ceremony as a process “like being hollowed out—thankful to know that one was only a mold—and being filled very slowly with some thin even fluid that would slowly harden.” Once this self has hardened, it can only reclaim its range of possibilities by breaking the mold of the marriage itself. “I really think romantic love is the great cul-de-sac of creative evolution. God’s big booboo,” Sophie’s friend Kate tells her. The novel sees divorce as an open road. Sophie is a writer, hard at work on a novel about a woman also named Sophie Blind. “With a book, whether you’re reading it or writing it, you are awake,” Sophie thinks. “In a book she knew where she was.”

Divorcing hints at this novel-within-a-novel to suggest that we are reading that novel, and to wink at our impulse to read it that way. In an interview with Benjamin Moser, Taubes’s son, Ethan, described it as “very autobiographical. It’s also stylized and it’s also a couple of different books.” Divided into four parts, the book does feel like multiple books sutured into one. Using the fissure of Sophie’s broken marriage as a portal through which to survey the rest of her life, Taubes travels back in time from the divorce to Sophie’s courtship, her parents’ courtship, their parents’ courtships, and eventually her own childhood. In these reassembled jigsaw pieces, I felt an author willing herself toward an unlikely dream of completeness—even as she knows that gathering all the pieces of her life won’t achieve the impossible goal of making them fully cohere.

Flitting between scene and fantasy, Sophie moves like a fugitive: a woman who has left her marriage and abandoned the structure of a recognizable plotline, a character who abjures the sturdy footing of any consistent tone. She is, by turns, wry, sorrowful, profound, crude, gleeful, reckless, prodigal, entitled, beleaguered, wounded, hungry, and adamant. The novel insists that all of these selves are part of her:

If only she could make up her mind about being in so many worlds. But she was of many minds. One mind said: I like to stay where I am. Where I am is the right place. Another mind liked to travel. It loved to be surprised; to lie down in one bed and wake up in another, in another country, another person…. Her third mind said you have to be careful.

Divorce isn’t a plot device that helps her decide, it’s one that lets her want all these things at once, and exposes every choice as an uneasy truce among contradictory minds.

Mother, dreamer, adulterer, zigzagger. Always, Sophie is a grieving woman who holds the memory of her marriage in her body: “That loss she carried in her very marrow, compacted with it,” like a teratoma, a tumor made of teeth and hair and skin, the ghost of a life that almost lasted. When asked why she is planning to keep her husband’s surname, Sophie “shrugs, smiling,” and explains that it’s like “a souvenir…like from the war. Call it a misadventure. Still a ten-year stretch of my life.” It’s one of divorce’s many bone-dry reminders: ultimately, perhaps, our identity is formed most powerfully by the parts of our lives we most want to forget.

I first read Divorcing a few weeks after signing my own divorce papers, in a Brooklyn high-rise on a freezing Valentine’s Day, a confluence that itself seemed lifted from fiction. Reading the novel, I found myself pulled in opposite directions by the gravity of two planets: Taubes’s life and my own. On the one hand, I was tempted to read the novel through the retrospective lens of its author’s impending suicide, to find in it the blueprints of her despair. On the other hand, I kept stubbornly searching for hope, for diamonds in the ash heap of its pain. It didn’t take a psychoanalyst to figure out why I was reading the novel this way: I wanted to understand my own divorce plot as one pointed toward rebirth. Perhaps my refusal to let the shadow of Taubes’s suicide color the entire book—to resist conflating novel with confession, or character with author—was a dressed-up version of an equally subjective impulse: the sharp tug of my own desire to find creative vitality and daily possibility on the other side of divorce.

This was a time for me of ceaseless domesticity. During the days, I baked cookies with my daughter, who was so proud to mix with her special red spoon. I filled our kitchen with ambitious new produce that I insisted she try—dragonfruits in their pink lizard skins, gooseberries in their husks, bitter melon I always cooked wrong—determined to see these as edible mascots of our adventurous new life. Once she was asleep, I sat at my laptop furiously trying to complete the extra freelance assignments I’d taken on to pay my legal bills, descending into anxious worry about what it would feel like for her to divide her childhood between two homes, and bingeing Love Island episodes about good-looking young people looking for other good-looking young people to fall in love with. It’s not falling in love that’s the hard part! I wanted to yell at my computer screen, but it wasn’t listening, only reflecting back the faint image of me and my bowl of ice cream, like a caricature of a divorcée.

The hope I wanted to find in Divorcing was the photo-negative of my own disillusionment—my fear that the end of my marriage had broken things that would never be fixed. This fear was true, but it wasn’t the only truth.

Reading Taubes’s novel, I kept thinking of an anecdote I’d once read about Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend, a 1945 film that follows the harrowing and ridiculous story of an alcoholic on a desperate bender. The first time the film was screened, it played with a jaunty soundtrack, and the whole audience laughed; at the next screening, they changed the soundtrack to something more somber, and the audience wept. Divorcing includes a similarly Janus-faced set piece. Before Sophie flies from Paris to New York to visit Ivan, they engage in a feverish transatlantic correspondence, exchanging the “fat letters” her children are so curious about. At one point she describes getting two of his letters in rapid succession: the second letter telling her to “‘disregard the first, written in a fit of madness,’ but saying essentially the same…. The first letter made her cry. The second made her laugh.” It began to seem like I could read and reread the entire novel in this way: crying the first time, laughing the next, or vice versa.

Part of the novel’s brilliance is its refusal to remain trapped in the tonal claustrophobia of either anguish or optimism. We watch Sophie weeping; we watch her heading out to Paris parties after her children are in bed; we listen to her being crass and snarky with lovers real and imagined: “Why do you have to have such a pot belly?” she asks one. “What do you have in there—quintuplets?” In Taubes’s hands, the divorce plot becomes a supple narrative device, one that can let all these tones—snark, grief, hunger, hope—exist in chorus.

In the novel’s opening scene, Sophie thinks, “Now I am dead I care only for truth”; “but I never felt so intensely alive as now.” For me, these lines caution against reading the novel as a prolonged suicide note, or finding only despair in its pages—I never felt so intensely alive as now. It is as if they were saying: a character lives here in perpetuity, more fully present than ever.

As befits a novel written by the daughter of a psychoanalyst about the daughter of a psychoanalyst, Divorcing is essentially analytic in its structure, moving backward in time to arrive at the formative wounds and desires of childhood. Reading this inverted chronological narrative feels like opening a series of matryoshka dolls to find a small girl running through the fields outside Buda with skinny Petie, a playmate with “short-cropped woolly hair” and a “marvelous” way of peeing, who told her they could run away to America by cutting the diamonds off his mother’s evening gown.

As if returning to the scene of a crime, the novel eventually reaches the unraveling of Sophie’s parents’ marriage:

From the way [her father] pronounced the word “divorce,” Sophie sensed it was something ugly, sad and terrible; but she didn’t know how to apply it to him or her mother or herself who were never really a family.

The novel pivots from young Sophie wrestling with the word “divorce” to Sophie as a mother navigating her own daughter’s questions about divorce decades later:

Can people change that much? Mummy, when you marry somebody can’t you know what they’re going to be like? Because when I get married I want to be absolutely sure. Did you think when you married Daddy that you might ever get divorced?

This tacking back and forth in time allows Taubes to dramatize, in a nuanced rather than reductive way, the connection between Sophie’s relationship with her husband and her relationship with her father. All her life, Sophie has been hearing from her father that “she was really in love with him and wanted to marry him and there was no point in denying it; that was part of her Electra complex to deny it.” One of the perils of being raised by an analyst! Sophie could see that even when she tried to shape an identity apart from him, he still wanted to control the ways she differentiated herself:

He offered her several ways of being different; he wanted her to be different in a way he could accept, understand…. She wanted to be different her own way, which he couldn’t understand or accept.

It’s ironic, but hardly coincidental, that a novel about a woman liberating herself from male influence—first her father’s, then her husband’s—would be savagely dismissed by a male critic. Hugh Kenner’s review of Divorcing in The New York Times in November 1969 was not so much laced with misogyny as structured by it. Kenner calls the novel a faddish and derivative work steeped in the “cat’s cradling of lady novelists,” as if the creative sensibilities of these “lady novelists” were all dresses purchased from the same boutique. Kenner dismisses the novel as a story in which “all that ever does happen is the beating of Sophie’s mind against the fact that she can’t stand her husband,” even as she depends on him. “Lady novelists have always claimed the privilege of transcending mere plausibilities,” he writes. “It’s up to men to arrange such things, and if your novel could use a globe-trotter’s decor, well, just assume that your principal male character (though a brute) could somehow arrange it.” It’s as if we could all accept that female consciousness is little more than a gaping maw hungry for the “arrangements” men can offer, when, in fact, one of the principal subjects of Divorcing is Sophie’s desire to craft a self that isn’t beholden to these arrangements—that wants to find out what her identity might look like beyond their scaffolding.

Divorcing ends with Sophie sitting in an airplane on a runway, observing the other planes move in their careful choreography like a flock of possible lives swirling around her: “Seat belt fastened, watch[ing] the handsome high-tailed jets skate slowly and stately to cocktail-hour music.” The first time I read this closing scene, it seemed full of possibility: divorce as a kind of runway, Sophie perched beside a window with all these possible futures circling around her. For her, divorce is less about seeking a single true self—the stable identity whose assumed existence inspires the pop-psychology call to “find yourself”—than about claiming the right to multiplicity.

But the second time I read the novel, its final scene felt more saturated with indecision and paralysis: all these anonymous metal beasts lurching around a rainy airport, lifting into flight while Sophie is doomed to stay on the tarmac. Even if divorce promises liberation from the self that has hardened inside the mold of marriage, the novel suggests, its freedom is terrifying, and stinks of death. No matter how long your life continues, you’ll always carry that death inside of you. The most heartbreaking part of divorce isn’t the acrimony; it’s the memory of all the affection, all the devotion, that came before.

The letters Susan and Jacob Taubes sent each other, recently collected and published in several volumes, testify to that devotion. They read like artifacts from a glorious but doomed civilization—a marriage charged by theological debate and fierce dialogue, full of geographic distance and superlative longing, an intimacy marked by communion but also by hunger. “My good child, I think of you all day long, how deeply we belong to each other, that the powers of sea and earth have no deeper and more secret sources than our love,” Susan wrote in September 1950, from the middle of a transatlantic boat crossing. And in an October 1950 letter, sent from Rochester to Jerusalem, “I am terrified to think that I exist at all in your absence—that we are two separate beings.”

In her search for a metaphysics of romantic love, Taubes reaches for the model of partners as two halves of one whole, drawing from the writings of Martin Buber:

We acknowledge that we are not identical with the ineffable I and Thou, but simply Susan and Jacob, who are not alone in the world, but one among many, many beings broken into man and woman, searching for each other, finding, but mostly perhaps not finding.

Perhaps for Taubes, the writing of Divorcing was an attempt to keep “finding” someone—not the husband, the thou, but the I who had been in such passionate and vexing communion with him, and who wanted to find new footing in the aftermath of their marriage. Ethan Taubes put it more bluntly: “I think my mother was a heartbroken romantic…. [Jacob was] the love of her life [and was] basically sleeping with everybody.”

In his introduction to the new edition of Divorcing, David Rieff calls it “a novel that bleeds,” and it does bleed, across boundaries of actuality and fantasy, across time. It certainly carries the bloody residue of pain and the imminent arrival of death. But the novel isn’t just bleeding. It’s crafted. It shapes pain into something intricate and searching. In one letter to Jacob, Taubes insists that, although “it is thought by some that in a great poem the poet is invisible…there is another kind of poem equally great, that is written with blood.” Her declaration of “another kind of poem” suggests another way to see Divorcing—not as a “novel that bleeds” but as a novel written in blood, using pain as a material rather than simply excreting it.

Taubes’s final scene is full of both inspiration and paralysis: Sophie grounded amid the planes, gaze pointed toward the sky. This open tarmac is not a happy ending. It’s more like a question. It makes no promises except that you can’t know what’s coming next. Its gray asphalt made me remember the open plaza outside the Brooklyn courthouse on a freezing day in February, walking from my lawyer’s office to the subway, striding quickly through the wind, headed home to my toddler because I only had the sitter for another half-hour.

That day was frigid, but also bright; the sun was suspended above me like a glistening eye. In her drawings that winter, my daughter had started to make messy yellow scribbles in the upper corner that she called “the cold sun”—trying to understand, I think, how a day could be full of light without being full of warmth. That day outside the courthouse I was living inside one of her drawings, under one of her cold suns. The chill was nearly unbearable, but the sky was huge and blue and wide-open like a door. Both things were true—the bitter chill of the wind and the vast blue expanse of the sky—and neither dissolved the other.

This Issue

May 13, 2021