At the core of the latest national reckoning over race is an incontrovertible fact: the Civil War killed slavery, but it did not kill entrenched racism and Black subjugation. One historical interpretation, lavishly publicized and increasingly in vogue, blames this not only on the tenacity of the defeated slaveholding South but also on the racism of the victorious North, and on the white supremacy upon which the nation was supposedly founded. Some white northerners may have claimed a commitment to political and civil equality for African-Americans, the argument allows, but they were a small minority and their commitment was wispy. Soon enough, after the war, that commitment vanished and, as is well known, the nation abandoned the formerly enslaved and their children to the violent overthrow of Reconstruction, the brutal imposition of Jim Crow in the South, and the continued subordination of Blacks everywhere else. Black Americans, so the argument goes, were left to fight on their own to salvage America’s false promises of freedom and democracy.

Northern white liberals might have fancied themselves ennobled by slavery’s demise, accruing overdrafts on what Robert Penn Warren called, in his brief, anguished book The Legacy of the Civil War (1961), a smugly hypocritical “Treasury of Virtue.” But today’s revisionists assert that the Civil War might better be described as a war between northern white racists and southern white racists over the expansion of slavery, which many northerners opposed in order to preserve a white man’s republic—a gruesome episode in a virtually seamless history of American white supremacy.1 After Appomattox, they claim, northern whites and southern whites reconciled and joined in building an industrial and later a postindustrial America predicated on Black subjection (and, not coincidentally, based also on the imperial subjugation of people of color from Cuba to the Philippines and beyond, not to mention the American West). White Americans then constructed and celebrated a national mythos that enshrined slaveholders and racists and imperialists as heroic shapers of America’s destiny—a mythos being toppled only now.

This interpretation, positing racial oppression as the nation’s core principle, might sound new, and it has clearly become more influential in reaction to Donald J. Trump’s election in 2016. It exploits, however, arguments that historians from varied perspectives have been developing for decades, especially the central claim that the pre–Civil War North was a racist bastion. In 1961, the same year that Warren’s book appeared, Leon F. Litwack’s North of Slavery offered a relentless account of white northern Negrophobia and Black persecution—of a racial order virtually unchallenged by whites and only rarely challenged by Blacks, in which, by the end of the 1850s, “change did not seem imminent.”2 A few years later, in a prominent essay that relied heavily on Litwack’s book, Warren’s friend and fellow southern liberal C. Vann Woodward laid out the case that northerners’ loyalty to white supremacy doomed Reconstruction.3 A string of similar studies on the antebellum period followed, attributing white antislavery opinion, especially in the Midwest, to the desires of racists to prevent slavery’s expansion and keep their own parts of the country lily-white. More recent scholarship has described New England as so disfigured by racism that by the 1850s, local Blacks lived as “permanent strangers whose presence was unaccountable and whose claims to citizenship were absurd.”4 Although the term “whiteness” only came into usage decades later, everywhere in the country, it seemed, across the political spectrum and on both sides of the slavery issue, whiteness and its elevation animated American life.

That view, however, has always had its critics, and recently a growing current of historical scholarship has, from diverse viewpoints, described northern racial politics very differently, calling the larger, now fashionable racialist interpretation into serious question. These writings do not deny the harsh racist realities that Litwack and others forced historians to confront. If anything, continuing research into, among other topics, the racist mob violence unleashed on northern Blacks has made them appear all the more oppressive. But building on older studies of northern free Black communities and Black abolitionists, some historians have recovered a rich history of pre-war Black resistance to northern racism absent in earlier, bleaker accounts. Others have disputed what James Oakes has described as a presumed “racial consensus,” in which northern racism was as uniform as it was intense. In fact, long before the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison established his landmark newspaper, The Liberator, in 1831, and then long after, white self-styled abolitionists organized not simply to hasten slavery’s eradication but to battle formidable racist legislation with significant success. They did so explicitly in the name of securing civil and political equality.5

The pre–Civil War North, it seems, was a landscape not of unremitting white supremacy but of persistent struggles over racial justice, inspired largely by the egalitarian ideas of the American Revolution, that were led by antiracist whites as well as Blacks and that actually overthrew anti-Black laws. These struggles helped in important ways to precipitate the war and culminated in the ratification of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, described by Eric Foner, among others, as a “second founding” that revolutionized, Foner writes, “the status of blacks and the rights of all Americans.”6 The crucial history of these antiracist politics, their connections to the triumph of American antislavery, and their influence on the rewriting of the Constitution after Emancipation are an enormous and, until now, largely untold story. Kate Masur’s Until Justice Be Done and Van Gosse’s The First Reconstruction go a long way toward telling it.

Advertisement

There is no shortage of books on Black politics in pre–Civil War America. For decades, historians have been assiduously reclaiming the lives and work of activists famous and obscure, ranging from abolitionist agitators to eloquent church and community leaders to fugitives from enslavement whose daring helped press the slavery issue to the center of national debates. Yet Masur, a historian at Northwestern, and Gosse, a historian at Franklin and Marshall, have expanded the field of study in important ways by examining antiracist as well as antislavery campaigns and by exploring Black involvement in more mainstream electoral politics. Apart from challenging the desolate view of northern racism, they also grapple with the tensions that arose between independent Black efforts and biracial politics, finding strains but also remarkable cooperation and amity among Blacks and whites.

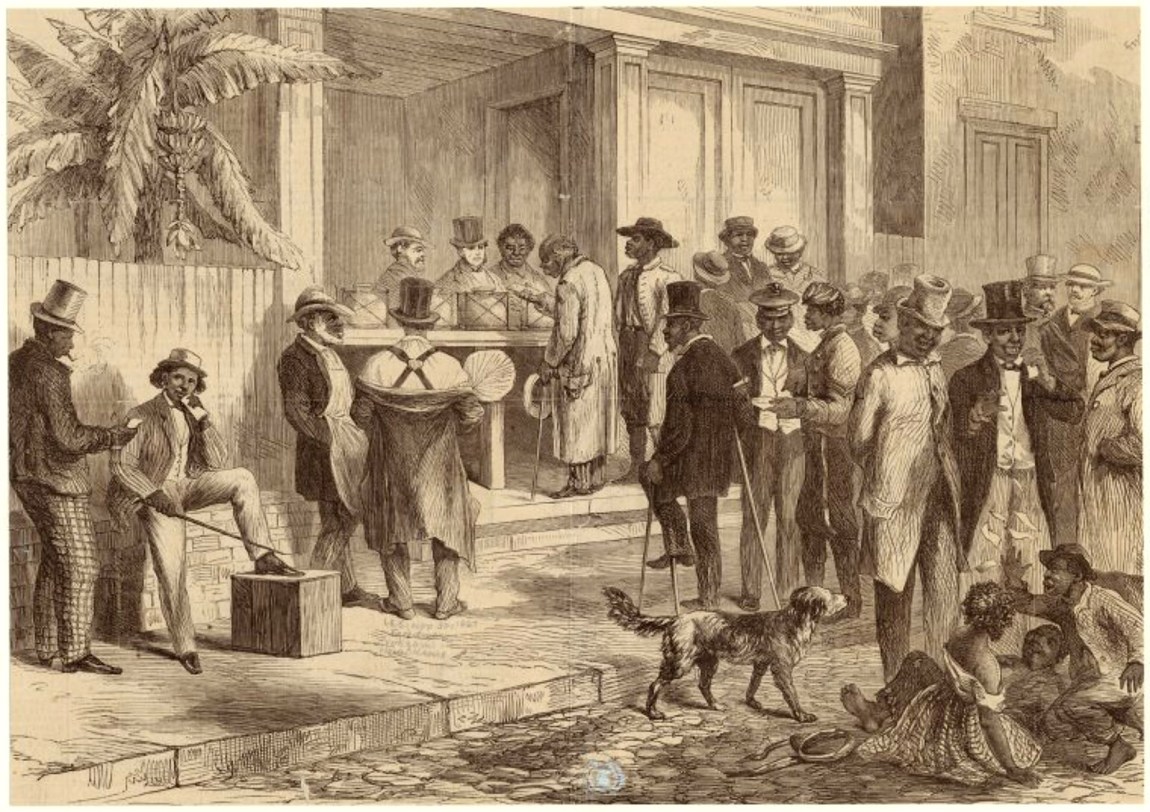

Masur’s subtitle, “America’s First Civil Rights Movement, from the Revolution to Reconstruction,” is a trifle misleading, insofar as the first civil rights movement she describes was for the most part an aspect of the larger antislavery movement. At a deeper level, though, it is telling, as is Gosse’s seemingly incongruous title describing Black electoral politics during the same period as “the First Reconstruction.” Between 1780 and 1804, all seven of the original states north of Delaware either abolished slavery or commenced its abolition, and beginning with Ohio in 1803, every state entirely north of the Ohio River or west of the Rocky Mountains that entered the Union—ten in all prior to 1860—did so with slavery formally barred. Yet almost everywhere, slavery’s elimination or exclusion led to discriminatory legislation and judicial rulings aimed at subordinating free Blacks or excluding them outright. Several states, including New York and Pennsylvania, restricted or eliminated political and civil rights that Blacks had previously enjoyed. Masur and Gosse are concerned with this repressive political aftermath of the first (or northern) phase of emancipation, hence their allusions to the first civil rights movement or the first Reconstruction.

The Articles of Confederation and then the Constitution left oversight of slavery in the hands of the state governments, and so, until the Civil War, the politics of emancipation and civil rights unfolded largely in the states. Likewise, states newly admitted to the Union without slavery had jurisdiction over the civil and political status of free Blacks. Accordingly, large portions of both of these books involve state politics, a level at which both authors operate with great skill.

Masur’s book, for example, a rich survey of antiracist politics, pays particular attention to Ohio, where Blacks and New England migrants clashed repeatedly with white southern settlers from Virginia and Kentucky, and whose legislature enacted the first of the so-called state Black Laws in 1803–1804. Carved out of the Northwest Territory, where the national government had banned slavery in 1787, Ohio nevertheless adopted a constitution that denied Blacks the vote, and its legislature later passed a series of measures that, as earlier legal histories of the laws observed, closely resembled southern-state slave codes, including one law discouraging settlement by requiring all Black residents to register with local authorities and another prohibiting Blacks from testifying in all court cases involving white people.7 The state’s “official” position, Masur writes, regarded free Blacks as, at best, “unwanted sojourners rather than fully vested members of the community.”

Despite the restrictions, African-Americans flocked to Ohio, drawn by economic opportunity and, it would appear, uneven enforcement of the residency restrictions. Early objections to the racist statutes arose from local Quakers (including the pioneer abolitionist of the day, Garrison’s mentor Benjamin Lundy) as well as in court decisions, above all a state supreme court ruling in 1831 that narrowed the reach of the Black Laws by defining any person with less than 50 percent “African” blood as white. Through the 1830s, Ohio’s branch of the Garrisonian immediatist American Anti-Slavery Society attacked the Black Laws head-on, as did separately organized African-Americans, most auspiciously in a statewide petition campaign in 1837 centered in Cleveland and led by a group that included John Malvin, a local carpenter and ordained Baptist preacher born free in Virginia. Yet the efforts got nowhere in the state legislature, as both of the major political parties, Whigs and Democrats, with some individual exceptions, were pledged to uphold the Black Laws.

Advertisement

The protests gained traction only after 1840, when politically minded abolitionists, Black and white, joined forces in the local version of the Liberty Party, breaking with allies who in their rectitude disdained partisan politics as corrupt. Often slighted as a minor precursor of the Republican Party of the late 1850s, the Liberty Party (succeeded in 1848 by the Free Soil Party) became a rallying point for intense antislavery activity but also, in Ohio, for continual efforts to repeal the Black Laws. Although they remained disenfranchised, Black activists were deeply involved as speakers and organizers, even as they attended their own conventions and, for a time, published an independent Black newspaper. Playing the two major parties against each other over civil rights as well as slavery, pushing the Democrats to such racist extremes that they alienated their own supporters, the movement finally killed most of the Black Laws in 1849, a victory unthinkable a decade earlier.

Masur finds the same pattern everywhere she looks: northern lawmakers insisted on upholding racist legislation, creating a backlash. While Blacks spurred the mobilizations, the numbers of white voters opposed to discrimination rose, and the working alliances between Black activists and white abolitionist politicians turned protest into politics. Meanwhile, antiracist politics also unfolded at the national level, focused on areas (above all the District of Columbia) where Congress reserved full jurisdiction. To be sure, Masur makes clear, the outcomes were never complete triumphs: in Ohio, for example, Black men would not gain the suffrage until 1870 and the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, which the state legislature only barely approved. Racism remained a constant in the North and in many places was a mighty force. Still, Masur concludes, “across the free states, Black activists had persistently and creatively demanded repeal, and growing numbers of white people had become persuaded that racist laws were unacceptable and un-American.” And they had won some remarkable victories.

Even more importantly, perhaps, the history Masur relates can also be understood as a long prelude to the Reconstruction amendments. The antiracist fights from the 1830s through the 1850s were a training ground in interracial civil rights politics that either produced or engaged figures who would be indispensable in the vital congressional battles over civil rights during and after the Civil War, including the Republican leaders Salmon P. Chase, Charles Sumner, Henry Wilson, and Schuyler Colfax, not to mention the agitator Frederick Douglass. While enacting legislation in 1861 and 1862 that helped pave the way for the Emancipation Proclamation, Masur shows, the Republican-dominated Congress, with President Lincoln’s help, “quickly took steps to enforce racial equality in civil rights in areas where it believed it had jurisdiction.” After Appomattox, these Republicans framed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which led in turn to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. The amendments effectively rewrote the Constitution by explicitly granting Congress the authority to protect individual rights in the states, including Black civil and political rights.

Masur neither idealizes her subjects nor denigrates them for failing to live up to some heroic activist ideal. “The many and diverse people who lent their voices to the movement,” she observes, “converged not around the most profound of anti-racist arguments, but rather around the straightforward demand that the nation accept the principle of racial equality, first in civil rights and then in political rights.” Their accomplishments were hard-fought, partial, and often precarious, yet real enough given all that their demand for equality was up against. Moreover, in helping to prepare a generation of reformers who went on to make sweeping legal change at the national level, Masur’s first civil rights movement helped create the tools and lay the foundations for modern civil rights reform—yet another major departure from familiar depictions of the white supremacist free states. And, as Gosse’s book demonstrates, that movement was not the only antiracist political force in the pre–Civil War North.

Until recently, neither studies of Black politics nor broader political histories of the era—including, I confess, my own—have had much to say about Black participation in and influence over the major political parties. (Black involvement in electoral politics, it seemed, was confined to the antislavery third parties.) This shortcoming has not stemmed, as Gosse erroneously asserts, from historians’ skewed assumptions that Black citizenship was irrelevant to the politics of the day. Political historians have long paid attention to some of the very struggles that he features, above all those over Black disenfranchisement. Rather, as if quietly accepting the grimmest views of northern racist society, historians have generally assumed that Black voters were so thoroughly shut out that their participation at this level of politics was marginal. Black activists appear as rebels, abolitionists, and fugitives from bondage, but not as Federalists or Jeffersonian Republicans, Jacksonian Democrats or Whigs.

In correcting that oversight, Gosse’s immensely detailed The First Reconstruction offers a revealing, at times startling reconsideration of early national and antebellum political history. Although Black disenfranchisement often followed emancipation in the North, much as it would in the post-Reconstruction South, it did not occur right away, nor did it occur everywhere. Where it did not occur at all, or until it did, free men of color sometimes voted in sufficient numbers to be an important swing constituency in closely contested elections. Furthermore, where Black voting was sharply curtailed short of elimination, there were still enough Black voters, along with enough districts willing to skirt the law, to ensure that in some places Black ballots sometimes mattered. Yet for Gosse the story involves far more than simply the number of Black voters: as a “political fact,” he writes, Black voting was “a collective practice, acknowledged by white political operatives”—an activity that created biracial partisan politics that in time included the Liberty and Free Soil Parties.

Curiously, Gosse relates, African-American electoral politics gained some of the smallest purchase in two of the five states that, between 1780 and 1784, adopted policies that at least gradually abolished slavery, Connecticut and Pennsylvania. Authorities in Connecticut, a virtual Congregationalist theocracy until after the War of 1812, adopted measures between 1812 and 1818 that barred Black voting until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. (The restrictions led to continual Black protests, including a series of petition campaigns in New Haven, Hartford, and smaller cities between 1838 and 1850, involving women as well as men, which Gosse surprisingly overlooks.) In Pennsylvania, a combination of what Gosse calls “caution and self-interest” regarding electoral politics on the part of Philadelphia’s otherwise impressive Black elite, combined with a pitting of white mass suffrage against Blacks by a southern-oriented Democratic Party, paved the way for Black disenfranchisement in 1838.

Greater tumult arose in Rhode Island, which enacted a gradual emancipation law in 1784. Blacks had made little impression on the state’s politics over the decades after the Revolution when, in 1822, they were suddenly disenfranchised, a setback that Gosse, like other historians, is at a loss to explain. That defeat was undone amid the crushing of the Dorr Rebellion of 1842, an uprising against the state’s small rural elite and its antiquated colonial-era charter, in which the victorious forces of order restored Black suffrage effectively at the expense of working-class whites, especially immigrants. Thereafter, the Black vote went solidly to the Whig Party, resisting even the entreaties of the Liberty and Free Soil campaigns. Rhode Island’s Black Whigs quickly became a significant force—“a black submachine,” Gosse calls it—strong enough to swing statewide elections and keep the Whigs in power until the party’s demise in the mid-1850s, after which the state’s Blacks shifted to the Republican Party.

Gosse devotes special attention—about one third of the book—to events in New York, where gradual emancipation came relatively late. After a thorough account of how Federalists and Jeffersonians competed for Black votes (with Federalists gaining the lion’s share), he retells in minute detail the oft-studied disenfranchisement of most New York Blacks in 1821. He follows with a more novel reconstruction of the persistence and growth of New York Black politics despite those restrictions, with African-American activists and voters displaying greater independence there than in other states, drawn to a rich world of antiracist as well as antislavery engagement.

Most striking of all, though, are Gosse’s descriptions of Black politics in northern New England. Massachusetts became the first state to abolish slavery entirely (by court decree in 1783), but three years earlier it had affirmed suffrage regardless of race in its state constitution. From the Federalist era down to the Civil War, Blacks not just in Massachusetts but also in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine (admitted as a separate state in 1820) voted alongside whites, sticking with the Whigs until the appearance of the Liberty and Free Soil Parties, then gravitating to the Republicans in the late 1850s. Although too small in number to affect statewide elections, Black voters and politicians gained significant influence in port towns and cities including Portland and New Bedford. “First in Massachusetts and then across the northern borderlands, white and black together,” Gosse writes, built “a nonracial polity,” or what two other scholars whom he quotes have called “a New England without races, at least as we have come to understand that term.”8

It is important not to get carried away by these discoveries. Even among the white Federalists and Whigs whom Gosse cites with admiration, for example, racism and even proslavery sentiments were hardly absent. The prominent Massachusetts Federalist Harrison Gray Otis, to take one case, may have belonged to an avowed antislavery and nonracialist clan, as Gosse justly remarks, yet he also, as a member of Congress in 1798, fiercely defended the necessity as well as the justice of southern slavery. Thirty years later, to be sure, the aged Otis made waves in defending the rights of the militant Black abolitionist David Walker, the author of an incendiary antislavery pamphlet that he managed to smuggle into the South, but not too much later, Gosse notes, influential Whigs whipped up the racist mob that notoriously pulled William Lloyd Garrison through the streets of Boston with a noose around his neck.

Still, Gosse argues persuasively not only that northern Blacks gravitated to the white operatives of the Federalist and Whig Parties but that they did so shrewdly, as a distinct political bloc, building their own bases of power inside as well as outside mainstream electoral politics. By the time sectional politics over slavery’s expansion blew those politics to pieces, northern free men of color had decades of political experience of every kind, and they brought that experience to bear, working with whites, in the battles that helped the first antislavery party in history attain national power. Thus, in the aftermath of slavery’s fitful demise in the North but well before the Civil War, Black voters and political operatives forged enduring lineaments of Black politics, aimed at securing equal voting rights and, beyond that, at securing the rights of equal citizenship—rights, Gosse firmly concludes, “not yet won” a century and a half later.

Neither of these books leaves a rosy impression of the American past, as if the arc of the moral universe has eternally bent toward justice. Although the stories that Masur and Gosse tell led to the Reconstruction amendments, they soon enough bent toward injustice, with the overthrow of Reconstruction, the imposition of Jim Crow, and the distortion of the Fourteenth Amendment and its guarantees of equal protection under the law into a bludgeon to protect corporate power by designating corporations as persons. “I know and all the world knows that revolutions never go backwards,” the antiracist Republican William Seward declared shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War. But Seward was wrong: revolutions can go backward, or at least get stopped in their tracks for so long that it might seem as if they had never happened at all.

Yet the revolution that ended American slavery certainly happened, just as the civil rights revolution of the 1960s did, followed by decades of conservative ascendancy that have culminated in a barely veiled recurrence of mass disenfranchisement wherever today’s Republican Party holds power. Not surprisingly, that prolonged ascendancy has flattened historical perspectives anew, replacing mythic narratives of inevitable progress with a pessimistic cynicism about the nation’s racial past. It is all the more remarkable, then, to learn how the antiracist politics that defined what is sometimes referred to as the Second Reconstruction of the 1960s originated not in the aftermath of the Civil War but at the nation’s founding, to be carried forward by two generations of Americans, Black and white, for whom the egalitarian ideals of the Declaration of Independence were anything but false. By recapturing that largely forgotten past, without sentimentalism or patriotic piety, Kate Masur and Van Gosse have written valuable works of history that speak powerfully to our own historical moment.

-

1

Several academics, filmmakers, and activists have recently pressed the white supremacy argument to posit that the Civil War did not actually abolish slavery but diabolically sustained it, because the Thirteenth Amendment permitted “involuntary servitude” as punishment for a crime. By that logic, white America cynically substituted the government for individual slaveholders and mass incarceration for chattel bondage. For a devastating critique of these and related interpretations, see Daryl Michael Scott, “The Scandal of Thirteentherism,” Liberties, No. 2 (2021). ↩

-

2

North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790–1860 (University of Chicago Press, 1961), p. 279. ↩

-

3

“Seeds of Failure in Radical Race Policy,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 110, No. 1 (1966). ↩

-

4

Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780–1860 (Cornell University Press, 1998), p. 3. ↩

-

5

See James Oakes, “Conflict vs. Racial Consensus in the History of Antislavery Politics,” in Contesting Slavery: The Politics of Bondage and Freedom in the New Nation, edited by John Craig Hammond and Matthew Mason (University of Virginia Press, 2011). On early abolitionism, see my “Abolition’s First Wave,” The New York Review, May 14, 2020. ↩

-

6

The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution (Norton, 2019), p. xx. ↩

-

7

See Stephen Middleton, The Black Laws: Race and the Legal Process in Early Ohio (Ohio University Press, 2005); and Paul Finkelman, “The Strange Career of Race Discrimination in Antebellum Ohio,” Case Western Reserve Law Review, Vol. 55, No. 2 (2004). ↩

-

8

James Brewer Stewart with George R. Price, “The Roberts Case, the Easton Family, and the Dynamics of the Abolitionist Movement in Massachusetts, 1776–1870,” in Abolitionist Politics and the Coming of the Civil War, edited by James Brewer Stewart (University of Massachusetts Press, 2000), p. 67. ↩