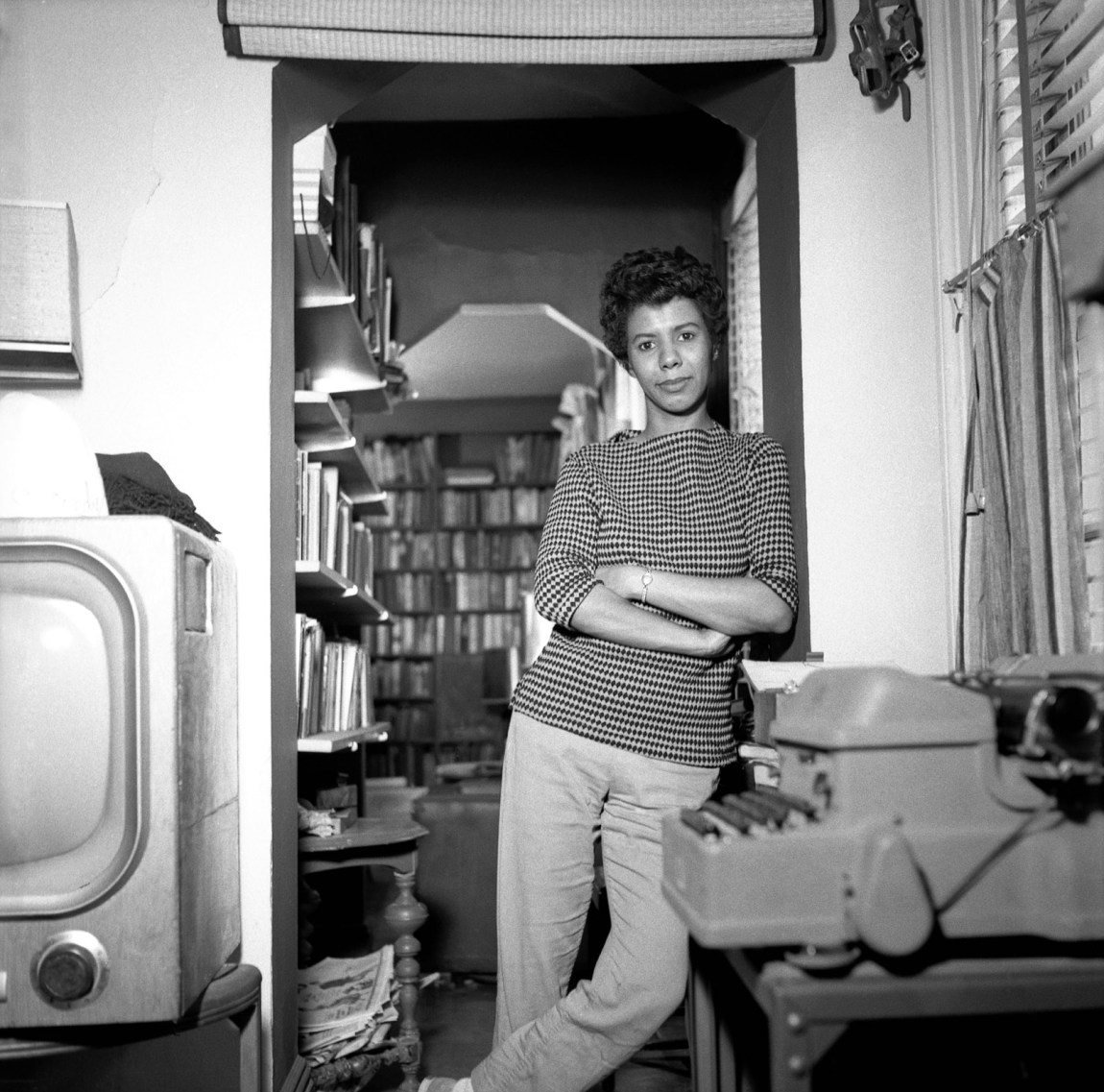

When I watch footage of Lorraine Hansberry—a striking enunciator and the fiery and brilliantly self-possessed Black woman best known for her play A Raisin in the Sun—I sometimes forget the sense of belatedness I felt when I wrote about her life in Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry (2018). I often worried that it was too late to fill the gap of decades when her work was neglected, although even now much of her writing is out of print or has never been published. Yet even so, hearing Hansberry’s voice brings a sense of possibility and the opportunity to recover her spirit as well as her legacy.

A Raisin in the Sun is likely the most widely produced play by an African-American playwright in history. It first appeared on Broadway in 1959, and Hansberry became the youngest winner of the Drama Critics’ Circle Award and the first Black woman to have a play produced on Broadway.

Her story began on the South Side of Chicago, where she was born into an affluent Black family in 1930. Her father had come from Mississippi, her mother from Tennessee. Her parents were “race people,” devoted to the collective uplift of all African-Americans. Lorraine grew up with a passion for reading and a keen interest in her Black working-class peers. Her father, a real estate developer, had innovated the “kitchenette” apartment buildings that flooded the South Side, one of the few neighborhoods in Chicago where Black people were not prohibited from living at the time. Her mother was a ward leader for the Republican Party. Their middle-class status afforded Lorraine a relative level of comfort in her neighborhood, but she grew up admiring the bold resistance and defiance of poor Black folks.

Lorraine was an intellectual and a voracious reader from adolescence on, though she was never much inclined to formal education. For two years she attended the University of Wisconsin, where she was a student leader in the on-campus Progressive Party, studied painting, and acted in plays. In the photographs of the women who lived in her dormitory, hers is the lone dark face, framed by straightened bangs and hair perfectly curled below her shoulders, and she wears dark lipstick. Though she looks like a fairly conventional coed, she was unusual. She integrated her dormitory, and she was personally transformed by a summer art program in Ajijic, Mexico, where she encountered artists and bohemians, many of them queer. Soon after, she dropped out of school.

Midcentury New York City, where Hansberry settled, was the home of Beat poets and Black activists, leftists and artists of every stripe. Hansberry said she’d been seeking an education of a different sort in Harlem and Greenwich Village. She embraced city life fully, working on staff and then as a journalist for Paul Robeson’s Black radical newspaper Freedom, and writing for left-wing publications like Masses & Mainstream. She wrote anonymous letters to The Ladder, America’s first lesbian magazine, as well as lesbian-themed short stories. And though her relationships with women were not public, they were a meaningful part of her political and intellectual life, as well as being integral to her sense of herself; she identified as a lesbian when that identity was routinely punished both legally and professionally.

Hansberry’s attempts at writing were at first intermittent. But her marriage to Robert Nemiroff, a leftist Jewish graduate student and songwriter who, unlike many men at the time, devoted himself to his wife’s brilliance, facilitated Hansberry’s emergence as an artist. Early on she waited tables at his family’s restaurant in Manhattan and worked at left-wing summer camps.

After writing a commercially successful song, “Cindy Oh Cindy,” Nemiroff was able to support Hansberry while she wrote A Raisin in the Sun, which takes place in a tiny and terrible kitchenette apartment in Chicago. The father of a Black family has died. They have been left with a sizable insurance check that the mother, Lena, says will be used to buy a house and send the daughter to medical school. The play is driven by the conflict presented when Walter Lee, the son, asserts his desire to become a businessman. As it unfolds, Hansberry’s play exposes the workings of classism, racism, and the politics of gender as each member of the family dreams of a life beyond the kitchenette.

An important new book, Conversations with Lorraine Hansberry, edited by Mollie Godfrey, situates Hansberry the playwright in her social and artistic milieu. Collections like this book—which includes interviews with Hansberry, reviews of A Raisin in the Sun, and an essay and work of short fiction by her—are, importantly, works of crafting and curation. I had read every one of these pieces multiple times while working on my own book. But as anyone who has ever written a syllabus can tell you, order and selection produce meaning. You want to provide a structure for a body of work, one that excites the imagination and deepens understanding—bringing certain elements, patterns, and truths into view. This collection does so elegantly.

Advertisement

Soyica Diggs Colbert’s brilliant new Radical Vision: A Biography of Lorraine Hansberry is a necessary companion to Godfrey’s collection.* A theater critic as well as a distinguished literary scholar, Colbert mines Hansberry’s work as both a playwright and essayist. What distinguishes Colbert’s work is that she deliberately traces the various social movements in which Hansberry participated—the homophile movement (early gay and lesbian rights activism), the Greenwich Village counterculture, and Black freedom movements—to chart both her political participation and her attendant intellectual and artistic development. As a scholar of African-American theater as well as literature at Georgetown University, Colbert is unparalleled in her understanding of both fields and Hansberry’s influence in each.

While Colbert’s biography is a narrative account, Godfrey’s collection provides some of the essential raw material that made Hansberry such a significant figure of the twentieth century. Godfrey, a professor of English who specializes in African-American literature at James Madison University, has revived a sense of Hansberry as a writer who was insightful and intellectual, tough and imaginative, a wonderful debater, and deeply engaged in the life of the mind. An unrehearsed conversation affects the listener very differently from a work of art. The Lorraine of Conversations reveals aspects of her personality that aren’t accessible in her prose alone; in these pages we get a glimpse into her frustrations, her place in the world, and how she understood it.

Perhaps most powerfully, the book deepened my sense of how being seen and seeing are, always, in tension for African-Americans, women, and queer people. When you are looked upon as an “other,” many people make assumptions and judge you according to them. Hansberry looks back at the viewer, refusing to be diminished, asserting her value and making herself heard.

Early reviewers of A Raisin in the Sun dismissed Hansberry while pretending to delight in her. They tried to make her a wunderkind housewife and cast her goofiness as unserious. Even more provocative than the criticism was Mike Wallace’s infamously offensive 1959 interview with Hansberry, which appears in Conversations. Here is one of the more uncomfortable moments:

MW: John Chapman, the drama critic for the New York Daily News, wrote that he has great respect for your play, but he feels perhaps that part of the acclaim may be a sentimental reaction—“an admirable gesture,” I think, is the way that he put it—to the fact that you are a Negro and one of the few Negroes ever to have written a good Broadway play.

LH: I’ve heard this alluded to in other ways. I didn’t see Mr. Chapman’s piece. I would imagine that if I were given the award [a New York Drama Critics’ Circle award] because they wanted to give it to a Negro, it would be the first time in the history of this country that anyone had ever been given anything for being a Negro. I don’t think it’s a very complimentary assessment of an honest piece of work…or of his colleagues’ intent.

MW: He says that A Raisin in the Sun—well, let me quote him. He said, “If one sets aside the one, unusual fact that it is a Negro work, A Raisin in the Sun becomes no more than a solid and enjoyable commercial play.”

LH: Well, I’ve heard this said, too. I don’t know quite what people mean. If they are trying to speak about it honestly, if they are trying to really analyze the play dramaturgically, there is no such assessment. You can’t say that if you take away the American character of something then it just becomes, you know, something else. The Negro character of these people is intrinsic to the play. It’s important to it. If it’s a good play, it’s good with that.

The deftness of Lorraine’s response—she always gave better than she got from dismissive interlocutors—is even clearer here, on the page, than in the video recording. Like a surgeon, she carves out racist assumptions, then recalibrates with honesty and historical awareness. It is a lesson in skill and circumstance. To be a Black artist has always required one to fight as well as create.

In other interviews we see the dance of interjection. Hansberry is talked over and fights for space. What I find most impressive is that she is never swayed from her point. She insists on being heard. Then as now, Black artists, once they achieve some success, are expected to hold themselves up as evidence that racism is a thing of the past—as representative of egalitarian American society. In other words, they are expected to lie or perform in exchange for recognition. It is a terrible pact, one that Hansberry always refused to make.

Advertisement

We might praise that today, but Conversations makes painfully clear how much pressure she had to withstand in order to refuse constraint and diminishment. It also has broader implications: the great Black artists of the past who are today celebrated were often insulted and derided in their time. Contemporary Black artists suffer the same conundrums and insults, and even at a moment when many are working to dismantle racism, they are often relied on for symbolism in lieu of real structural change.

These challenges facing Black writers are evident in a discussion titled “The Negro in American Culture,” which features Hansberry, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Emile Capouya, and Alfred Kazin. Capouya, an essayist and critic, argues that race and racism are important social topics but ultimately secondary to other questions of political concern. Hughes, Baldwin, and Hansberry—each with a distinct and sophisticated take on imperialism, militarism, American racism, and the role of the artist—argue about the centrality of American racism. It was in this conversation that Baldwin said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.”

Baldwin goes on:

So that the first problem is how to control that rage so that it won’t destroy you. Part of the rage is this: it isn’t only what is happening to you, but it’s what’s happening all around you all of the time, in the face of the most extraordinary and criminal indifference, the indifference and ignorance of most white people in this country.

Now, since this so, it’s a great temptation to simplify the issues under the illusion that if you simplify them enough, people will recognize them; and this illusion is very dangerous because that isn’t the way it works.

That is to say, the experience of injustice is not an individual matter, and therefore remediation in the form of personal acclaim cannot be an effective form of change. These writers, like those who preceded them and those who followed, were met with deliberate ignorance and claims of innocence and challenged by the culture that seemed to celebrate them.

Hansberry’s complex relationship to the mostly white theater world is apparent in Conversations. She was a woman often misunderstood or mischaracterized even as she was acknowledged and ostensibly celebrated. But the book also offers an opportunity to discover how her relationships with fellow Black writers and activists were strikingly different. Her conversations with Lloyd Richards, the director with whom she worked, are particularly illuminating.

Richards was a genius with a remarkable history. He staged A Raisin in the Sun in 1959, and in 1984 he introduced another of the greatest American playwrights, August Wilson, to Broadway with Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (recently released as a film on Netflix, with Chadwick Boseman in his final role before his death last year). The sincere friendship between Richards and Hansberry, and their shared artistic vision, are evident in their conversations. They are subtle and reflective when speaking with and about each other. Richards on the response to A Raisin in the Sun is especially poignant:

One of the most exciting, and I think this accounts for a great deal of the audience acceptance of it, was, I think it gave something that I’ve seen very few plays do recently, and that is it gave the audience a chance almost to participate and to participate experientially…. This is a thing that I haven’t seen happen in plays very much, to the point that people just get involved in it, and they feel with them, and they hope with them, and they pray with them, and they enjoy with them, and they laugh with them and really become a part of it.

Richards staged Hansberry’s work in a way that allowed viewers intimacy with the characters. His stage directions and attention to emotional registers created an architecture of relationships such that each character could emerge with respect to the others. This invited the audience to see the world as the Black people in the play do.

That is a critic’s observation, but this book does something that the critic cannot. Conversations with Lorraine Hansberry allows the reader to hear the artist in dialogue without the filter of the biographer or documentarian. This is a collage of reflection, delight, and self-defense, from the dawn of Hansberry’s career as a playwright to the posthumous recognition of her immense impact. The student of Hansberry should have the unfiltered stuff, too, and this sequence of encounters reveals her place in the world.

That said, I found myself wishing the editor had included background for each conversation. Some readers would surely benefit from knowing more about the cultural significance of the speakers and, in some cases, the connections between them. For example, in an interview between Hansberry and the talk show host and producer David Susskind, he speaks about his disappointment in Tennessee Williams’s characters in Sweet Bird of Youth, which appeared on Broadway the same season as Raisin in the Sun. Susskind claimed to be unable to identify with Williams’s debased and tragic southern white characters—very different from the hoop-skirted mythos of Gone with the Wind, the nation’s conventional idea of the South—while he could identify with the Black working-class people in Hansberry’s play. Hansberry skillfully challenges this evasion so common among white liberals of the Northeast hoping to distance themselves from white supremacy. She sees common concerns between her own work and Williams’s, such as poverty and despair, but also the potential for liberation that exists in the Black imagination, harder to come by for poor white southerners, given the irresistible power of whiteness. Knowing something about Susskind and Williams deepens one’s understanding of the pointedness of this exchange.

Hansberry’s essay about how A Raisin in the Sun fits into the history of American theater more broadly is one of the most powerful aspects of Godfrey’s collection. “An Author’s Reflection: Willy Loman, Walter Lee, and He Who Must Live” is a masterwork of criticism. In it, she notes that audiences did not see the clear connection between Arthur Miller’s antihero and her own Walter Lee (their shared initials are a clue) because of the way that race overdetermines how people read even fictional characters. And yet they are clearly united by a tragic American masculinity: “The two of them have virtually no values which have not come out of their culture,” Hansberry writes, “and to a significant point, no view of the possible solutions to their problems which do not also come out of the self-same culture.”

Hansberry had a remarkable ability to be her own critic. She found herself frustrated by the lack of critical engagement with her plays, and so she dissected her own projects herself. These were not exercises in vanity—she was quick to recognize the flaws in her work. But they were lessons in how to read her plays, and by extension other Black plays, with critical and intellectual seriousness. Her essay is a model of how to recognize Black theater not as siloed or ghettoized, but rather in relation to the whole American theatrical tradition.

Hansberry wrote poetry, short stories, and novellas in addition to plays. All of us who have written about her wish that readers had access to more of this work. Nemiroff, her ex-husband and executor, tried unsuccessfully to publish a number of pieces and instead settled on the publication and production, in 1968, of To Be Young, Gifted and Black, a play about her life adapted from her writings, later made into an autobiography with the same title (also the title of a 1969 song composed by Hansberry’s friend Nina Simone). But there is still much more—some of it is lyrical, some philosophical, and some historical.

Hansberry wrote brilliant character portraits, such as the fictional vignette included in Conversations called “Images and Essences: 1961 Dialogue with an Uncolored Egghead Containing Wholesome Intentions and Some Sass.” It is one of a number of dialogues inspired by Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, wherein she mocks existentialism, rejecting the idea of absurdity even as she withholds from the reader clarity about who is speaking. In the dialogue, one of Hansberry’s characters says:

I think that Western intellectuals, as typified by Camus, are really most exercised by what they, not I, insist on thinking of as the “Death of the West.” It is at the heart of all the anguished re-appraising, the despair itself; the renewed search for purpose and morality in life and the almost mystical conclusions of strained and vague “affirmation.” Why should you suppose Black intellectuals to be attracted to any of that at this moment in history?

We are now in a different moment, a post-post-colonial world and post-post-civil rights era. So much has changed, and yet so much of what Hansberry concerned herself with—countering economic exploitation and unfettered capitalism, fighting for feminist, queer, and Black liberation and against militarism—remains pertinent today. New movements and new forms of domination have entered our lives in the era of Me Too, the climate crisis, and an expanded network of surveillance technologies, but critics as well as ordinary people remain exercised over the question of the West and the rest. We still live with the assumptions and legacies of European empires, established with whiteness at their center. The fear that this centrality might erode is a persistent undercurrent in the creative world, even as white people continue to dominate in publishing, theater, and the arts in general. Today Hansberry remains a potent conversation partner as we navigate a fraught and conflicted world.

-

*

Yale University Press, 2021. ↩