One morning a few years ago, as I entered the York Street subway station in Brooklyn, a friendly young woman handed me a promotional T-shirt from the office-leasing company WeWork. It was gray and very soft, and it said “HUSTLE HARDER” in a graffiti-like font. It became a gym shirt, then a dirty-household-projects shirt. Recently I was going to throw it away, but it felt like a memento—of what, I wasn’t sure. It had always been tricky to say exactly what WeWork was.

In 2008 the company’s cofounders, Adam Neumann and Miguel McKelvey, were working in the same postindustrial Brooklyn office building—just two blocks from the York Street station—when Neumann alighted on the idea of leasing a floor of a nearby building and renting out desks to freelancers and entrepreneurs. (He was then running a baby clothes company he’d founded during college, and McKelvey was a draftsman at an architecture firm.) That spring, in the midst of the financial crisis, they opened Green Desk, with workstations consisting of Ikea butcher-block tables separated by glass walls. The business took off. A year later Neumann and McKelvey sold their stakes to the building’s owner and sought their fortunes in Manhattan’s depressed real estate market.

Their new company, WeWork, took out commercial leases (initially floors, then entire buildings), renovated the spaces, and subleased desks and private offices on flexible terms. Its tenants, called “members,” were individuals and small businesses. WeWork embodied the post-2008 recovery’s optimism about certain forms of professional labor under fractious economic and social conditions. “Do what you love,” WeWork told us. “Make a life, not just a living.” “Better together.” No more institutional drudgery or lonely gig work. The creative classes could gather in hip spaces and pursue their “life’s work”—selling luxury bedsheets or health insurance, building gay dating apps, idiot-proofing website design—while enjoying a feeling of community. Eventually, Fortune 100 companies wanted to join the party. Neumann, who grew up in Israel, said he was creating “a capitalist kibbutz.”

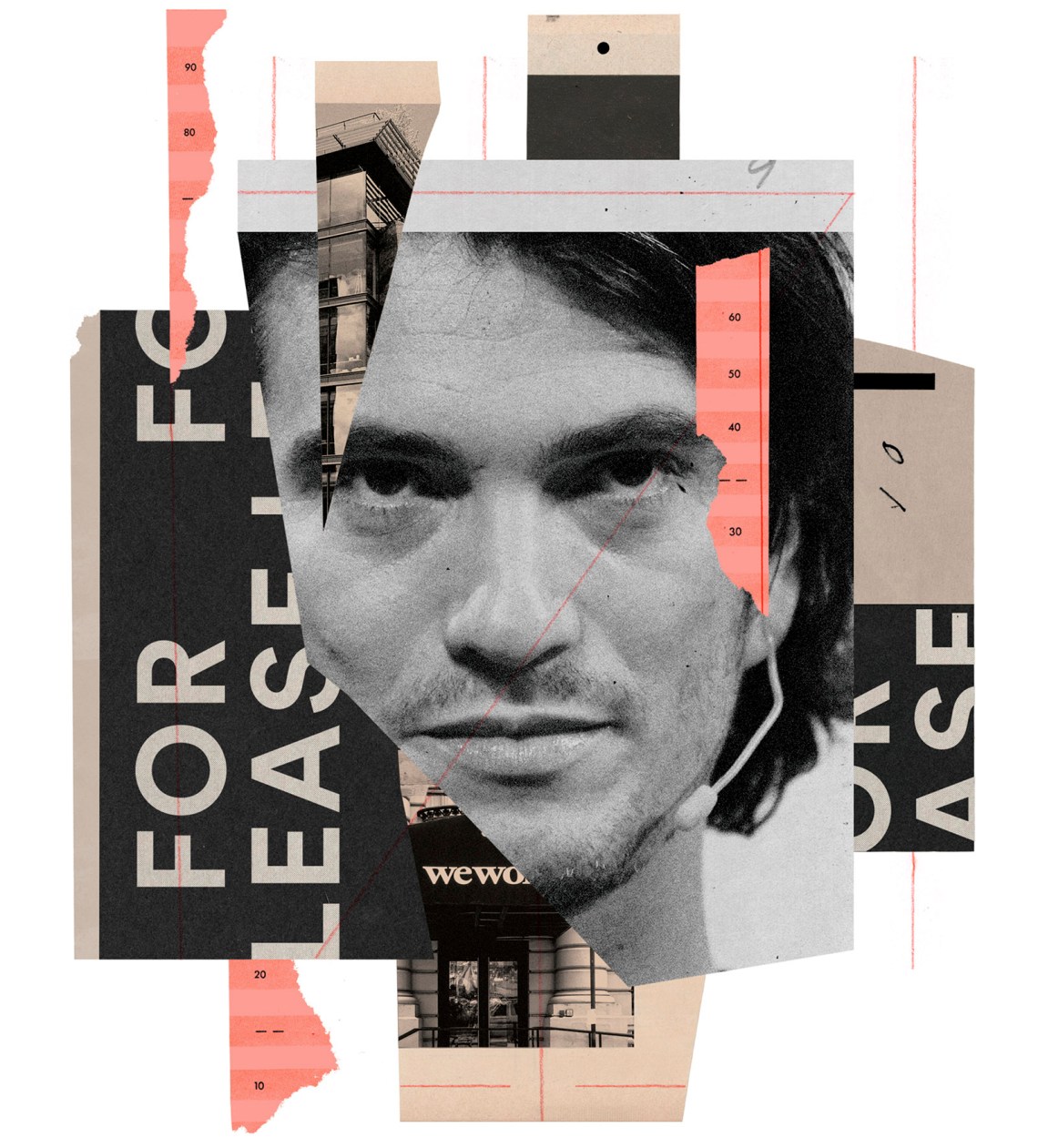

As of 2019 this relatively tame, capital-intensive operation had snowballed into a supposed valuation of $47 billion, making it second only to Uber among US start-ups. Neumann, six foot five, with a lion’s mane, a Svengalian gaze, a Kabbalah bracelet, and a limitless supply of enthusiasm and nonsense, was inseparable from this success. He wore flimsy designer T-shirts that drooped under the weight of clip-on mics, walked around the office barefoot and spoke of “energy,” showered booze on WeWork employees and potential business partners, and lathered up crowds at company events by promising a revolution in how we work. Sophisticated investors were won over. WeWork had raised more than $10 billion by 2019, including $4.4 billion from the Saudi-backed Vision Fund, run by the Japanese company SoftBank—the second-largest private investment ever made in a US start-up. And its revenue was doubling nearly every year.

Neumann’s charm and boosterism and even the company’s staggering rise could not counteract the wider world’s skepticism once an IPO prospectus was released in August 2019. It revealed enormous losses, the absence of any substantive corporate governance, and audacious self-dealing by Neumann—including renaming the parent entity the We Company and then charging it $5.9 million to acquire his trademark on the word “We.” “This is not the way everybody behaves,” a former CEO of Twitter said. Public investors weren’t interested, and the offering was canceled. And following a Wall Street Journal article detailing Neumann’s over-the-top, tone-deaf behavior, he was ousted as CEO.

The media’s intense interest in WeWork, then and thereafter, tended to center on Neumann’s frat-boy antics, New Age argle-bargle, and cartoonish messianism—he spoke of bringing peace to the Middle East and saving the world’s orphans. After his wife, Rebekah Paltrow Neumann, a cousin of Gwyneth Paltrow, was retroactively elevated to cofounder, she was widely ridiculed for her haute-hippie cluelessness and for such proclamations as “A big part of being a woman is to help men manifest their calling in life.” (The actual cofounder, McKelvey, who had three inches on Neumann but less showmanship, took on muted executive roles.)

Yet as several journalists have suggested, WeWork’s precipitous change in fortunes cannot be explained through the Neumanns’ hubris or delusion alone, though their fall provides ample material for schadenfreude. A confluence of cultural and market trends drove WeWork’s expansion and collapse and made the company, in the words of the Bloomberg columnist and former investment banker Matt Levine, “the absolute limit case of unicorn craziness.”

WeWork didn’t invent shared or flexible office space. In The Cult of We, the Wall Street Journal reporters Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell point to a California attorney who in the 1970s created a collection of office spaces with shared amenities for small law firms and solo practitioners. The better-known predecessors were a company called Regus, which had been providing “serviced” (fully furnished, pay-as-you-go) offices since 1989, and an activist-flavored “coworking” movement that sprang up in San Francisco in 2005. The latter had given rise to free or low-cost spaces for people to “work alone together,” an alternative to sitting at home (a place of temptation and torpor) or in a coffee shop (where one might spend hundreds of dollars a month for ambience and a power outlet).

Advertisement

WeWork’s vibe was Silicon Valley staff lounge crossed with boutique hotel lobby. The design and perks evolved over time, but the constants were natural light, industrial-chic elements such as raw ceilings and comfortable yet stylish furniture, and lots of free beverages (good coffee, fruit-infused water, and kombucha and beer on tap). The desks, which started at $150 per month, were densely packed—with an average of fifty square feet of floor space per member, roughly a fifth of that per employee at a traditional office—so that people would be forced to interact and might have one of the serendipitous encounters that have become a staple of the coworking industry’s sales pitch. (In 2016 Neumann claimed that 70 percent of WeWork members collaborated with one another, though he didn’t specify what he meant by “collaborate.”) Even those who kept to themselves could enjoy feeling, as the journalist Gideon Lewis-Kraus has written, “marginally more productive and slightly less unmoored.”

By 2015 WeWork had fifty-four locations across North America, Europe, and Israel, and more than 30,000 members. Large firms, whose sterile offices had become a symbol of corporate soullessness, started renting a floor or two, or even an entire building, from WeWork. American Express, Microsoft, IBM, and Amazon joined, and the last quickly became its biggest subtenant.

As an employer, WeWork offered the excitement and unpredictability of a tech start-up and the feel-good culture of a values-based, mission-driven organization. In Billion Dollar Loser, Reeves Wiedeman, a contributing editor at New York magazine, describes the chaos—sometimes fun, sometimes not—of working for WeWork. A motley crew of early employees, including a high school student who served as the head of IT, had “amorphous roles” and spent late nights assembling those Ikea tables. An architect who found himself doing menial errands was told by Neumann that he was “working at the next Google.”

By 2015 the company was hiring seasoned executives looking for a change of scene, as well as hordes of eager millennials just out of college or fleeing dull or low-ranking jobs. On a recent podcast, a former WeWork employee recalled cleaning up vomit and condoms after office parties; he said he would take the job again because it was fun. Wiedeman mentions a young woman who was so enthusiastic about her job that her sister worried she was in “some kind of capitalist cult”; the sister then joined and found WeWork to be refreshingly “anticorporate.” “Every one of us is here…because we want to do something that actually makes the world a better place, and we want to make money doing it,” Neumann told a crowd of employees at the company’s raucous, multiday annual retreat, called Summer Camp, held in the Adirondacks. Brown and Farrell observe that, as opposed to Wall Street’s naked mammonism, start-ups backed by venture capital “managed to marry extraordinary wealth creation with the pursuit of utopianism.”

Everyone was hurtling into the future, with Neumann leading the way. They were on a rocket ship, he liked to say—and the rocket fuel was vast infusions of cash. Early on, he was able to raise nearly $7 million from family and friends; through his sister, Adi, a successful model, and his wife, Rebekah, then an aspiring actor, he had entered a world of rich New Yorkers willing to throw a little money at a friend’s venture. (Wiedeman notes that “most co-working operators were lucky to cobble together six figures’ worth of investment.”) The financial advantage WeWork had on its competitors started growing by orders of magnitude.

When the Silicon Valley investor Bruce Dunlevie visited WeWork locations in New York in 2012, he felt, as he had with eBay fifteen years earlier, something “that you couldn’t quite put your finger on.” (His $6.7 million investment in eBay had turned into a $5 billion stake.) That year his firm, Benchmark, led WeWork’s Series A funding round with $16.5 million. Soon mutual fund managers—traditionally conservative but tired of missing out on the Twitters and Facebooks, according to Brown and Farrell—wanted in. And the head of JPMorgan was intent on making the bank the leading adviser for Silicon Valley companies looking to go public.

Neumann was a fluent pitchman, and his vision went far beyond office space. He promised a LinkedIn-style member network so that those serendipitous encounters could happen virtually, too. He sketched out WeLearn (a school), WeMove (a gym), WeEat (a food delivery service), WeBank, WeSail, and WeLive, dorm-style apartment buildings with large common areas that Neumann hoped would disrupt the residential market. “WeWork Mars is in our pipeline,” he said in 2015. Although some of these ventures didn’t take off, by late 2016 WeWork had raised $1.7 billion from investors, including JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs, and was valued at $16 billion.

Advertisement

Then, in 2017, Masayoshi Son, the head of the Japanese conglomerate SoftBank and its affiliated Vision Fund, a $100 billion pool dedicated to technology start-ups, decided within twenty minutes of meeting with Neumann to invest $4.4 billion; the agreement was sketched out on an iPad in the back of a car as Son traveled to his next meeting, with Donald Trump. Son told Neumann he wasn’t “crazy enough,” and that he should make his company “ten times bigger.” Neumann pursued a strategy known as “blitzscaling”—crushing competitors by offering submarket rates (and sometimes months of free rent), and plunging into new markets. (“Is that a city or a country?” Neumann asked about Kuala Lumpur; the first location there opened soon after.) In just a year, WeWork expanded from one hundred to two hundred locations. Rebekah opened WeGrow, an elementary school whose curriculum included meditation, robotics, and picking produce at the Neumanns’ Westchester estate that students then sold at WeWork’s headquarters.

While the Neumanns followed their whims and luxuriated in their wealth—five homes, five children tended to by three nannies (uniformed and chosen for their resemblance to one another so as to obscure their true number)—WeWork’s core business was beset by internal problems. The office-leasing operation’s enormous size should have brought enormous savings, but according to Brown and Farrell, “waste was everywhere.” In 2018 spending hit $3.5 billion against revenue of just $1.8 billion. There were organizational inefficiencies, such as multiple teams working on the same project and managers acting capriciously. Junior designers placed bulk orders of orange sofas from China and warehoused them in New Jersey, only to have the head designer decide that “orange isn’t working.” Replacements were purchased at retail prices; a few of the rejected sofas were sold to WeWork employees for a pittance and the rest went to landfills.

In 2018 Son, who believed that “feeling is more important than just looking at the numbers,” promised another infusion, this time of $20 billion. “WeWork is the next Alibaba,” he told SoftBank’s shareholders. (Son’s investment of $20 million in the e-commerce company, in 2000, is now worth around $150 billion.) Others were less sanguine. When the governments of Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi, the two largest investors in Son’s Vision Fund, refused to support the WeWork deal, Son decided to put up his own firm’s money. SoftBank’s telecom unit was about to go public, and he expected to raise more than enough to cover the WeWork investment. But the IPO was one of the worst debuts in Nikkei history, and SoftBank’s stock itself dipped by more than a third from the time Son and Neumann had begun discussions. Son called it off, then offered $2 billion. WeWork needed more. A few months later, as the Neumanns finished celebrating Adam’s fortieth birthday in the Maldives, the company announced that it was preparing to go public.

An S-1 is a document that typically provides the first opportunity for IPO investors to see audited financial statements for a US company, as well as details of its business model and corporate governance. When WeWork’s S-1 was released, readers reacted with amusement and alarm.* The goofiest bits were a prefatory dedication “to the energy of we” and an art-directed photo spread, both of which were Rebekah Neumann’s ideas. Among the most concerning bits: losses were keeping pace with revenue, Adam had a highly unusual twenty votes per share, Rebekah got to help select his successor, and it turned out that he co-owned several of the buildings from which WeWork rented space.

For some observers, Charles Duhigg wrote in The New Yorker last year, WeWork’s prospectus “laid bare a basic truth”: that the company’s dominance “wasn’t a result of operational prowess or a superior product,” but rather “because it had access to a near-limitless supply of funds” from investors. Bill Gurley, a partner at Benchmark, wrote a post on his blog Above the Crowd in 2015 warning that his fellow venture capitalists were suffering from FOMO—a fear of missing out—and weren’t doing enough to test whether a given business model “actually works.” Brown and Farrell conclude that FOMO led to “groupthink on a massive scale.” Scott Galloway, a business professor, is more blunt: the company’s outsized valuation was a “consensual hallucination.”

Much of the investor mania sprang from the notion that WeWork was somehow a technology company, one that would create “the world’s first physical social network.” The tech team grew to 1,500 employees, but the member network never took off, and the company’s data analysis and machine-learning projects yielded underwhelming insights: noise was a problem in densely packed spaces, desks next to windows were preferred over others. Tellingly, Neumann presented WeWork as a “platform.” Becoming a platform was, Wiedeman writes, “a goal shared by every ambitious start-up of the decade, no matter how specious the claim.” As Neumann put it, “We happen to need buildings just like Uber happens to need cars, just like Airbnb happens to need apartments.” There was some truth to this: they all engaged in arbitrage, squeezing efficiency out of existing resources. But Uber and Airbnb don’t take on costly, long-term leases for the cars and homes they offer. And unlike these sharing-economy giants, WeWork didn’t help create the economic precariousness that enabled its business model; it simply lionized the already existing figure of the hard-hustling, institutionally unmoored freelancer or entrepreneur.

With little to show on the tech front, the Neumanns started calling WeWork a “community company.” “Are there other community companies out there, or will you be the first ever?” a skeptical reporter asked them in 2016. WeWork was increasingly dependent on large enterprises, whose employees had little opportunity to interact with members outside their organizations. Even WeWork’s coworking spaces were not particularly social. In 2017 its research department conducted a study called “Are Our Members Friends?” The answer was no, which sat oddly with Neumann’s assertion that 70 percent of members collaborated.

One thing Neumann did not call WeWork was a real estate company. The irony was that the company had actually disrupted the commercial real estate industry, an impressive feat. In 2018, eight years after opening its first location in a run-down building in SoHo, WeWork passed JPMorgan as New York City’s largest private user of office space. As of 2019 WeWork had more than 527,000 memberships across 528 locations in twenty-nine countries. Fifty-one percent of Fortune 100 and 38 percent of Fortune 500 companies were members. The streamlined new model “struck fear in lots of people” in the real estate industry, a former WeWork contractor told me.

Admitting that WeWork was, fundamentally, in the real estate business would have put a ceiling on its valuation. Each building could generate only so much revenue—unlike with software, which can expand its user base unfettered by brick and mortar. (Two Fidelity analysts said as much in 2014; their concerns were not heeded by their bosses, who were eager to invest.) The appropriate comparison, it turned out, was not to Facebook or Twitter, or even Uber or Airbnb, but to Regus, now named IWG, which had been providing flexible offices for three decades. According to a Harvard Business School analysis, in 2019 Regus was by most metrics outperforming WeWork, yet the former was valued at nearly $4 billion and the latter at $47 billion. (The business model may be the same, but Brown and Farrell rightly credit WeWork with tapping into a younger, urban demographic in a way the stodgy Regus didn’t.)

Had Son not bought into WeWork’s vague techno-scalable potential, the company might have gone public earlier and at a saner valuation. But Son, who has a reputation for acting on instinct rather than analysis, and who designed the Vision Fund to be spent within five years, “decided to deliberately inject cocaine into the bloodstreams of these young companies,” a former SoftBank executive told Duhigg. Indeed, it was after Son’s investment that Neumann truly went wild. To the confusion of those around him, he invested in a company that made wave pools and one, started by a famous surfer, that sold turmeric-infused coffee creamers. He invested in the Wing, a buzzy, “girlboss” women’s coworking space. He pitched the CEO of Airbnb on a collaboration to build and rent out 10 million apartments, which would have cost $1 trillion. Perhaps Neumann was still heady from Son’s deranged whisperings that by 2028 WeWork would be worth $10 trillion.

Once it became clear, following the public’s reaction to WeWork’s S-1, that Neumann was a liability to the company, the investors turned on him. The bankers did too. They all urged him to resign, and Dunlevie threatened to break his arm if he didn’t. This is a dramatic moment in both books, and one feels some sympathy for the wounded Neumann—a bit like Uber’s Travis Kalanick, who in the midst of one PR crisis writhed around on the floor moaning, “I’m a terrible person.” (An excellent book about Uber, Mike Isaac’s Super Pumped, makes the case that Kalanick’s ouster, led by Benchmark, was a sound business decision.) Then one remembers certain other scenes, like Neumann’s following a somber speech at an all-hands meeting regarding the firing of 7 percent of the staff with rounds of tequila shots and a surprise performance by a member of the old-school hip-hop group Run-DMC. Or his sitting in meetings with his executive team and being served meals prepared by his personal chef while everyone else sat hungry, then bringing the plate to his face to lick it clean.

Any tale of Silicon Valley hype in the 2010s will be haunted by the specter of Theranos, the blood-testing company whose founder, Elizabeth Holmes, faces charges of defrauding investors, doctors, and patients regarding the effectiveness of her company’s technology. Commentators have likened Neumann to Holmes, as well as to Billy McFarland, a cofounder of the Fyre Festival, which promised a luxury bacchanalia in the Bahamas but delivered makeshift tents and cheese sandwiches. (McFarland was sentenced to six years in federal prison for defrauding investors.) Such comparisons are strained.

Neumann claimed, to staff and in public statements, that WeWork was profitable when it was not, but he wasn’t an extravagant liar. Yet there is a distinct whiff of grift about him. He treated WeWork’s Gulfstream as his private plane and had company executives spend weeks trying to get a cell phone antenna next to one of his houses removed, because of Rebekah’s fear that 5G electromagnetism might harm their children. He cashed out a total of $700 million in stock, in what Brown and Farrell say was “one of the most lucrative sales of stock of any US startup CEO before an IPO or sale”—a violation of the taboo against founders dumping shares, which might suggest a lack of confidence in the company.

In explaining why the WeWork board of directors did not do more to curb Neumann—and indeed approved nearly every proposal he submitted—Duhigg points to two developments: venture capitalists’ fixation on creating unicorns (start-ups with valuations exceeding $1 billion) and their concomitant desire to be seen as “founder-friendly,” unlikely to interfere or ask questions. Whereas venture capitalists of yore “prided themselves on installing good governance and closely monitoring companies, VCs today are more likely to encourage entrepreneurs’ undisciplined eccentricities.” They have become “co-conspirators” with “hype artists” such as Neumann.

The bankers who advised WeWork on its IPO have also been cast by the media as enablers, less persuasively. JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley competed for the coveted lead advisory position. In the interview process, Goldman pitched a valuation between $61 billion and $96 billion, which pleased Neumann greatly—and which later scandalized journalists. Yet Matt Levine has suggested that the bankers did nothing out of the ordinary; they were “talking up WeWork to WeWork” in order to get hired, after which they would conduct the due diligence and determine if the model checked out. Their optimistic projections—which were based on Son’s bullish $47 billion—encouraged Neumann’s singular obsession with valuation right up to the moment of collapse.

When Neumann agreed to step down, SoftBank was forced to rescue WeWork from insolvency by injecting $3 billion plus buying $3 billion in shares from existing investors, with a total valuation at $8 billion. Neumann, always looking out for me over we, negotiated an exit package that included forgiveness of his debt for personal expenses. He walked away with $1.1 billion in cash and a $500 million loan, a payout that angered board members as well as employees, many of whom were laid off in the following months—once the company had enough cash on hand to pay severance costs. SoftBank later reneged on the deal, and Neumann sued. In February the parties reached a settlement favorable to him.

Brown and Farrell call the WeWork story “a vital parable of the twenty-first-century economy.” But what is the WeWork story? The sheer loss of shareholder value would seem to make this one of the big business stories of our time. It has the trappings of a corporate thriller: oodles of cash, epic dysfunction, and a swift reckoning for the cult leader. But there’s something slippery and lesson-defying about it. What is revealed is that this fellow was a good storyteller (and very tall), some excitable investors gave him too much money with too little oversight, and it turned out he didn’t know how to run a company and was also pretty selfish.

Some observers, intent on finding a moral in the story, have suggested that the canceled IPO is a case of capitalism doing its job by saving mom-and-pop investors from ruin. If anyone was harmed, the argument goes, it was deep-pocketed private investors. (Of course, there were also thousands of employees who lost their jobs; some had trusted that the stock options they accepted as part of their compensation would make them rich.) But as Brown and Farrell note, the markets have short memories. Disappointing IPOs by Uber and the e-cigarette company Juul had turned investors off “monstrous startups with enormous losses,” and WeWork arrived too late; yet by late 2020 money-losing start-ups were “back in vogue” in the public markets. In December 2020 the SoftBank-backed food delivery service DoorDash, buoyed by pandemic lifestyle changes, debuted with a $39 billion valuation; the next day, Airbnb began trading at $47 billion.

With an unseemly number of post-mortems—two books, two podcasts, a documentary, and two forthcoming scripted TV series (one is based on The Cult of We; the other, based on one of the podcasts, will star Jared Leto and Anne Hathaway as the Neumanns)—it would be easy to miss that WeWork is still a going concern, led by an unglamorous CEO with a background in real estate. And the company might yet claw its way into the future of work, for reasons its founders and backers could not have anticipated.

The coworking industry had long worried about how the business model would fare in a recession, but the pandemic was far worse than a weak economy: the very idea of sharing space with other people was suddenly frightening. With the shift to work-from-home, many tenants did not renew their leases. Occupancy in coworking spaces fell to 51 percent in the fall of 2020, down from 78 percent in February of that year, according to a survey. Although WeWork aggressively cut costs (by closing more than a hundred locations and renegotiating leases on at least as many, and reducing staff by 67 percent from its peak) and found some new customers (such as universities seeking to spread out their student populations), by the end of the year its global occupancy rate had dropped to 47 percent and its losses totaled $3.2 billion. IWG also had big losses. Knotel Inc., a “flexible workspace platform” and one-time unicorn, filed for bankruptcy in January, though its troubles predated the pandemic. The Wing was saved from bankruptcy in February by IWG.

This year, however, coworking companies are expected to see increased demand. At least half of US workers who can plausibly work remotely would like to continue doing so at least some of the time, and 82 percent of US companies plan to allow that—an acknowledgment that the forty-hour in-office setup is often a hollow convention (though one that is fiercely missed by some). A hybrid model, combining remote and in-office work, seems likely to become prevalent and to benefit providers of flexible space. Large organizations may use such offices as satellite locations or for ad hoc projects; smaller businesses may opt for a model that is primarily remote, with space rented for meetings as needed; companies of all sizes may rent desks to give individual employees an escape from home (“work from near home,” as the journalist Cal Newport, writing for The New Yorker’s website, put it). This spring I did a free trial month at the WeWork location near the York Street station; I was relieved, for the sake of my concentration, to find my floor of small, glassed-in private offices largely empty, save for several men silently gaming or trading unknowable assets on enormous monitors.

The coworking companies are avoiding onerous leases as they shift their business model away from subleasing and toward revenue-sharing with landlords, and the industry is finding ever-more-efficient ways to commodify space. Before the pandemic, a start-up called Spacious helped high-end, evening-hours restaurants operate as coworking venues during the day. (WeWork acquired Spacious in 2019 and shut it down by the end of the year.) A new start-up called Codi allows people to turn their homes into offices during the day; hosts can rent out “seats” in their living rooms, in a formalized version of freelancers gathering at a friend’s apartment. These are the true Airbnbs of offices, creating a world in which every usable space is pregnant with the possibility of generating revenue. Meanwhile, WeWork, eager to capitalize on the pandemic’s fragmenting effects and well positioned to do so, announced in March that it will go public later this year, at a sensible-seeming—but who knows?—valuation of $9 billion.

-

*

The company, renamed the We Company in January 2019, reverted to WeWork in October 2020. ↩