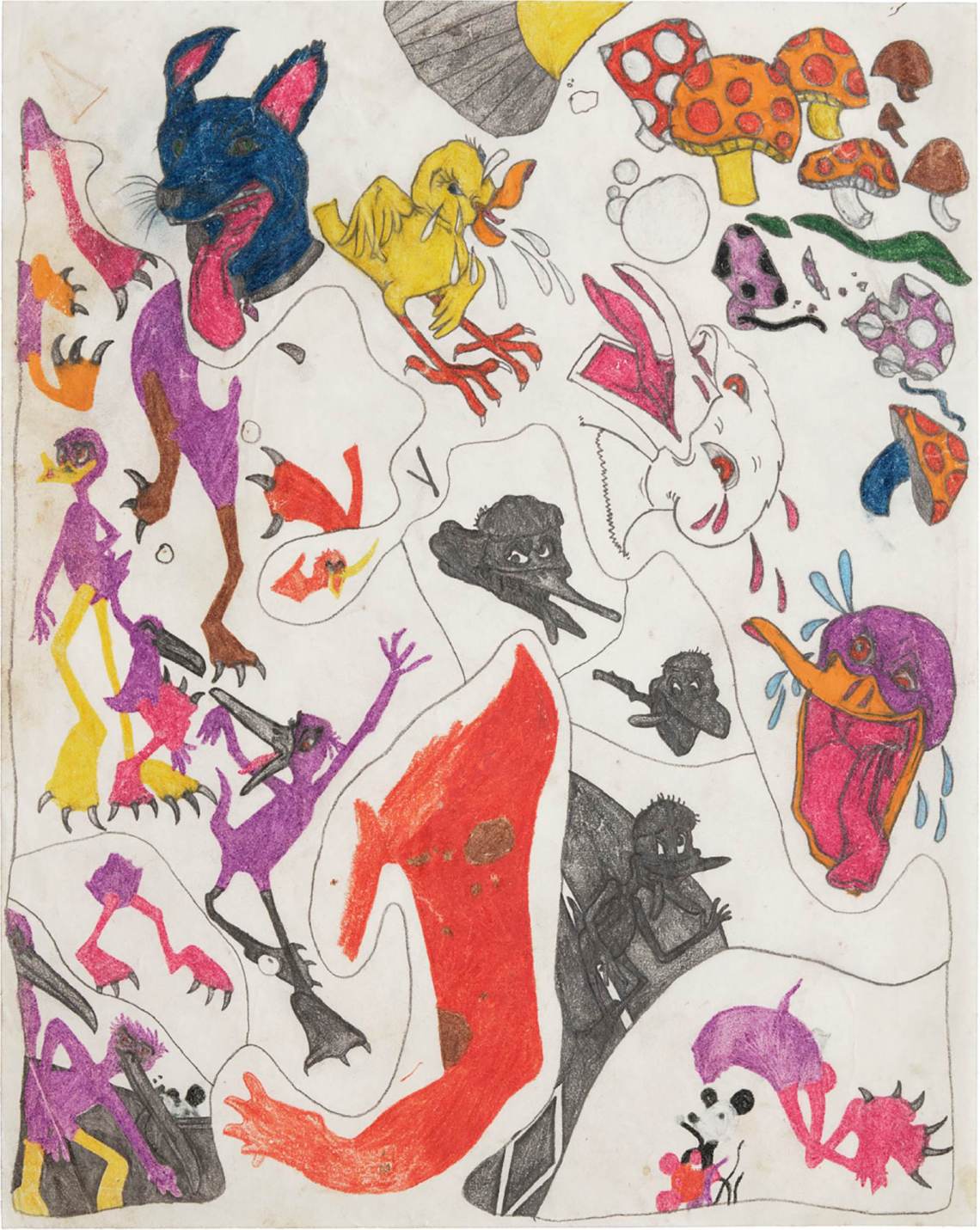

The words “down under,” which have long been almost synonymous with Australia and New Zealand, might come to mind when thinking of the work of Susan Te Kahurangi King. This is not merely because she is from New Zealand. It is because her art presents a kind of visual, psychological, and expressive upside-down world. In pictures she has been making since the late 1950s—even before she was a teenager—she has created a vast, riveting, and often bewildering universe. It is also a sometimes funny and surprisingly erotic realm, one in which people, animals, cartoonish people, and actual cartoon characters, such as Donald Duck and Bugs Bunny, all appear to have equal significance for her.

In King’s mostly small drawings—she does only drawings—distinctions between these supposedly “real” and “imaginary” beings become erased. She does not draw Donald or Bugs or a character out of Coca-Cola advertising referred to as Fanta Man with an ironic detachment. Her fat Fanta Man, with his wide mouth, snaky, wandering tongue, empty eye sockets, lewdly pliant fingers, and birthday party crown cap, is a kind of underground lord of the revels. Her ducks, Donald or otherwise, with their sometimes long, thick, projecting tongues, can actually be a little frightening—when they do not seem exasperated or irritated.

A small feast of King’s extraordinary drawings is currently part of an absorbing and knowledgeably assembled group show at the Andrew Edlin Gallery in New York. Entitled “Parallel Phenomena” and organized by Damon Brandt, it also includes the work of Carroll Dunham, Gladys Nilsson, and Peter Saul. Though not emphasized at the exhibition, its underlying point is to bring King, who in the press release is called “self-taught,” together with artists who are “credentialed and academically trained.” The idea, it would seem, is to break down the standards imposed by “an ill-informed hierarchy.”

This is a fine ideal, and one hopes that there will be more such mingling of artists coming at their work from very different backgrounds. But it should be noted that King is not exactly “self-taught,” in the sense that she seems not to have had a period of trial and error. We feel that her earliest pictures, though not on the same level of complexity as work she would go on to do, are already characteristic of her. In the biographical accounts of King, we read that she was diagnosed, after years of medical examinations and hospital stays, with autism spectrum disorder, because of which she lost her ability to talk. She has been silent since childhood, so we do not know what her pictures mean to her.

She has come to her themes, however, on her own. The majority of the works on view are from her teenage years through her twenties and present, especially in the earlier pieces, images of human and animal threat and commotion. From them, her drawings became more softly toned and more about uniformity, which she conveyed in scenes of, for example, long-legged and gargoyle-faced people ranked closely together. Entirely nude, or wearing bathing trunks or sexy leggings, these narrow-bodied figures almost seem to form walls or waves. The taste we get of them reminded me of Aubrey Beardsley. They have the same kind of exquisite preciseness. By the early 1990s, though, King’s desire to draw left her. It only came back in 2008 when she began to make abstract, weaving-like images, which she continues to do today.

That we have King’s large body of work, along with descriptions of its many changes in direction over the years, is due to her family. Her maternal grandmother, who took her under her wing from very early on, and later her mother, were especially attentive and caring. It was her father, who for a period pursued the teaching of the Maori language and was something of a visual artist himself, who gave King her middle name, which means “the treasured one” in Maori. Now seventy, she has been watched over by members of her own generation of the family—she is the second-oldest of twelve children—and by members of the next generation. A younger sister, Petita Cole, has for some time been in effect her voice to the world.

King was first widely recognized as an artist less than ten years ago, at an art fair in New York, and the enthusiastic response her work has since received from American artists may make her a better-known figure here than in New Zealand. The excitement of her images owed a lot to the edgy, threatening tone with which she could show panting creatures or strong-willed cartoon characters nearly colliding into one another. But the power of her work also derived from her freewheeling and almost anarchic sense of the inner space of her scenes.

Advertisement

She could draw on one section of her piece of paper and blithely leave the rest blank. She said no more than she wanted to say. A viewer was put almost instantly in touch with her willfulness. And in their assurance her pictures felt more modern or contemporary than the works of other outsider masters, whether Martín Ramírez, Eugen Gabritschevsky, or James Castle. Not that she seemed to be a more substantial figure; but a picture of hers could have a new kind of abruptness, in spirit and as a composition, and I think this pulled younger artists into her orbit.

As it happens, there is an uncanny similarity between King’s realm of squawking, unsettling creatures, along with the unexpected lubricity of her images—in one amazing untitled drawing, Fanta Man appears to be fondling another Fanta Man’s buttock—and the work of a number of American artists. At the “Parallel Phenomena” exhibition, it may be hard at first to get one’s bearings: all the pictures are small to medium-sized works on paper, and there are no wall labels to alert us immediately as to whose work we are looking at. The entire exhibition seems to be coming from some kind of “down under.”

The gentlest of the group, Gladys Nilsson, has long been associated with the Hairy Who movement of the 1960s, the Chicago artists who sought to flout the various dicta about the importance of abstraction coming from the New York art world of the time. She does it by making fanciful tableaux of awkward and gawky figures of every shape and size. Peter Saul, who was also underway in the early 1960s and chafed, too, at the New York art world’s widely held belief that abstraction and formal, impersonal values presented the only road to significance in contemporary art, countered it with some everyday bad taste. Guns, toilet bowls, lamps sticking up and slightly curving like penises, murderous thoughts in cartoon bubbles, and ducks falling on their faces—what is it about ducks?—crowd his pictures in the exhibition, which date from circa 1960 to 1964. The offhand way he laid in the elements in these bulletin-board-like pictures—and his assertive, unfussy colors—may make these works seem fresher today than when they were created.

The work of Carroll Dunham, however, is about a deeper, more inward, and instinctively derived kind of disruptiveness. His art, which took off in the early 1980s, might be described as a single, ever-changing, ongoing open house for all the thoughts and images—whether about sex, violence, art, anything—that squirm in our minds and that we generally keep to ourselves. His picture in the show entitled Land (1998), in which gun-toting and knife-wielding blockhead characters hold forth from a chunk of land in the sea, is like a daydream of combat, defensiveness, and sexual appetite. At least that is how we read the genital shapes that randomly adorn the scene.

Of the artists in the exhibition, Dunham and King seem closest, in that one senses there is something unpredictable and of the moment about how they come to their images. This may be because of their respective feelings for drawing. Dunham is known for his paintings, drawings, and prints, but his art seems to stem from his drawings. He appears to ask for little more from life than a blank sheet before him and a pencil in his hand. King, too, we read, needs no more than a piece of paper (even torn or written on already) and the most rudimentary pencil, pen, or crayon. The two artists, it turns out, both like presenting mouths as big, clumping machinery, with teeth that could bring down redwoods.

For most viewers, though, “Parallel Phenomena” will be about King, if only because she is still becoming known, while Dunham is by now a fixture of American art. The roughly two dozen works by her, moreover, will be new even to viewers of her previous works in this country. Were I the head of a drawings department at a museum, I would make a pitch for the purchase of all of them. Almost every one takes its own course.

One of the finest, although in its grayed orange tones it does not initially stand out like her more brilliantly colored sheets, is an untitled work from circa 1969 whose chief character is a big duck who appears to be bouncing up through a night sky, or perhaps gliding down from it. In the layered, cloud-and-sky space of the work (if these zones can be read descriptively), arms, faces, and hands of other creatures eventually become visible, all leading to our delighted discovery of a tiny person in a complicated costume, zooming off into the sky. But then another surprise awaits when we find a very subtly placed bent leg in a stocking, which goes up to the top of the thigh. It is a startlingly erotic touch, and all the more powerful for being easily missed. Making us not see things at first, we realize, is one of the strengths of King’s mysterious and playful art.

Advertisement