In 1959, after he had given three lectures in the West German city of Darmstadt on the principle of indeterminacy in music and then staged a series of concerts across Western Europe, the avant-garde composer John Cage became a star on Italian television. He appeared on Lascia o Raddoppia?, a popular quiz show hosted by a man called Mike Bongiorno every Thursday night at nine o’clock. The program, based on The $64,000 Question, was a manifestation of the Americanization of Western European culture after World War II. It fused capitalist incentives—lots of cash—with the display of recondite expertise. A contestant answered a question on a favorite subject. The questions got harder every week. A correct answer doubled the contestant’s prize; a wrong answer halved it and ended the game.

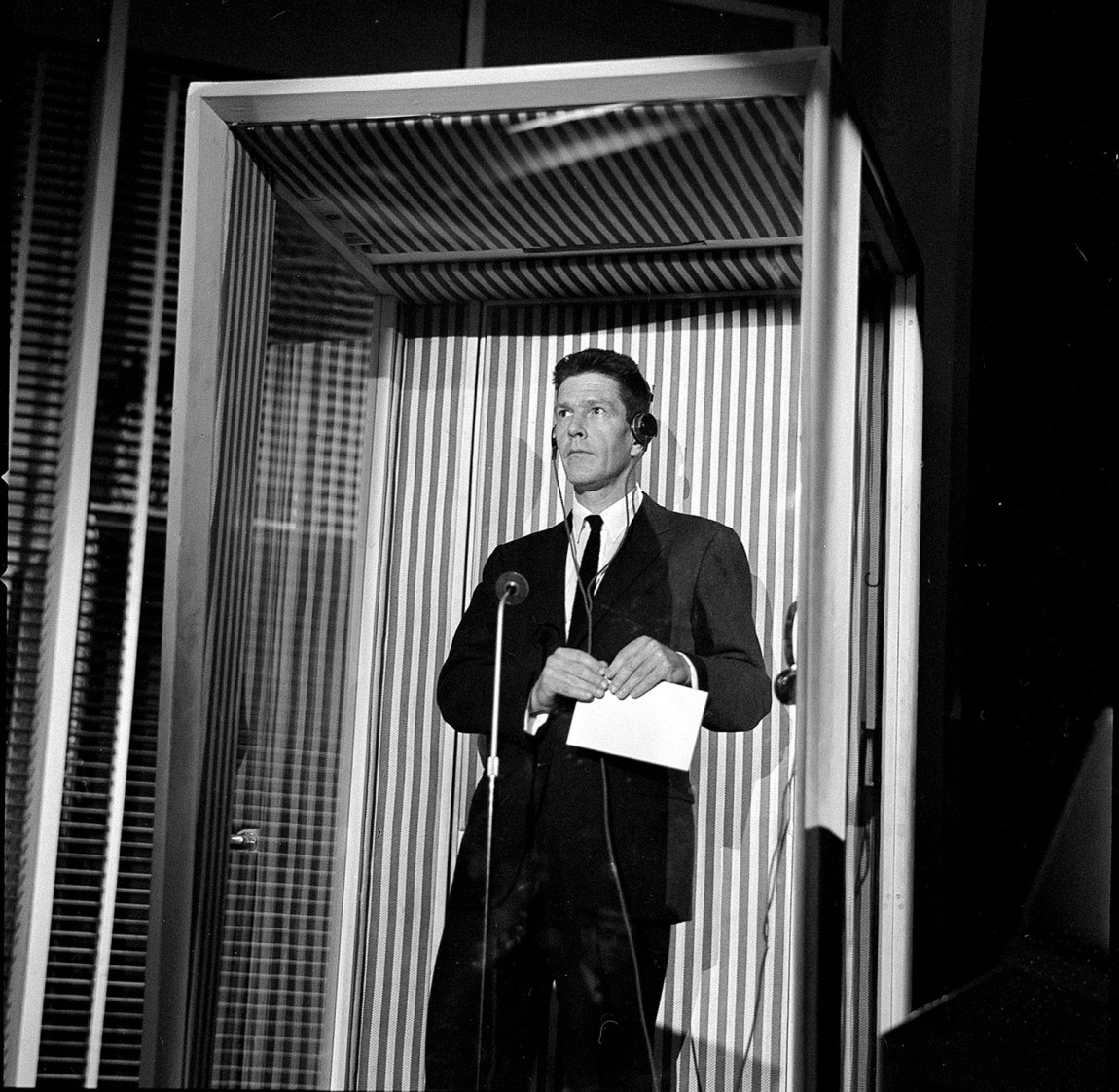

Cage, who was then working in a music studio in Milan, applied successfully to compete on the show, answering questions about one of his obsessions: mushrooms. The twist was that he would also perform a short piece, beginning with his composition for prepared piano, Amores, and eventually including a collage of random sounds he’d recorded in Venice. Cage got to the fifth and final week of the game, with more than five million lira at stake. He was placed in a glass-walled isolation booth, and Bongiorno asked him to name every type of white-spored mushroom.

There are twenty-four, and Cage had to list them all before a clock that he could not see ticked away his allotted time. What he could see was the audience frantically gesturing toward him as the clock ran down. He proceeded calmly through his answer, reaching the twenty-fourth white-spored mushroom almost exactly as time ran out. The jackpot, the equivalent of $6,000, was enough to buy a Steinway piano for himself and a Volkswagen bus for the dance company of his close collaborator Merce Cunningham. He also became famous in Italy. The press depicted him as the archetypal American man: tall, square-jawed, “pleasantly reminiscent of Frankenstein.” Federico Fellini considered casting him in La Dolce Vita.

All this might prompt the terrifying question with which Bob Dylan stopped the hearts of critics six years later: “You know something is happening but you don’t know what it is/Do you, Mr. Jones?” It is easy to imagine Cage’s five-week odyssey on Lascia o Raddoppia? as a work of art, a wonderfully outlandish Dadaist happening. The title of the show translates roughly as “double or quits?,” connecting it to the ludic method of composition and choreography developed by Cage and Cunningham, which used the throw of a dice to determine the next note or move. The random collision of elements—avant-garde music and cheesy game show, money and mushrooms, capitalist accumulation and artistic vision—is not so far from Robert Rauschenberg’s contemporaneous development of visual “combines,” composed of wildly disparate materials.

As Louis Menand puts it in The Free World, his joyous plunge into the cross-currents of Western culture in the 1950s and 1960s, such methods were meant to suggest “the coexistence of unrelated stimuli.” The Italian press image of Cage as pleasantly reminiscent of Frankenstein could be an ironic counterpoint to his lectures at Darmstadt, in which he denounced traditional musical scores that require performers to obey the will of the composer—he said they had “the alarming aspect of a Frankenstein monster.” The mushrooms might evoke the great terror of the cold war: the mushroom clouds of nuclear annihilation.

An overeager historian could see this whole performance as a provocative commentary by Cage on mass media, fame, and culture. In truth, he really did need the money, which was by far the largest amount he had ever earned. He really did know an awful lot about mushrooms and liked to show off his expertise. He had accumulated, according to his biographer David Revill, “not only mushroom manuals, but a mushroom ashtray, a mushroom tea towel, a clip-on plastic mushroom and a large tie bearing a mushroom motif.” Italian viewers knew exactly what was going on—a charmingly weird American was trying to win a lucrative prize.

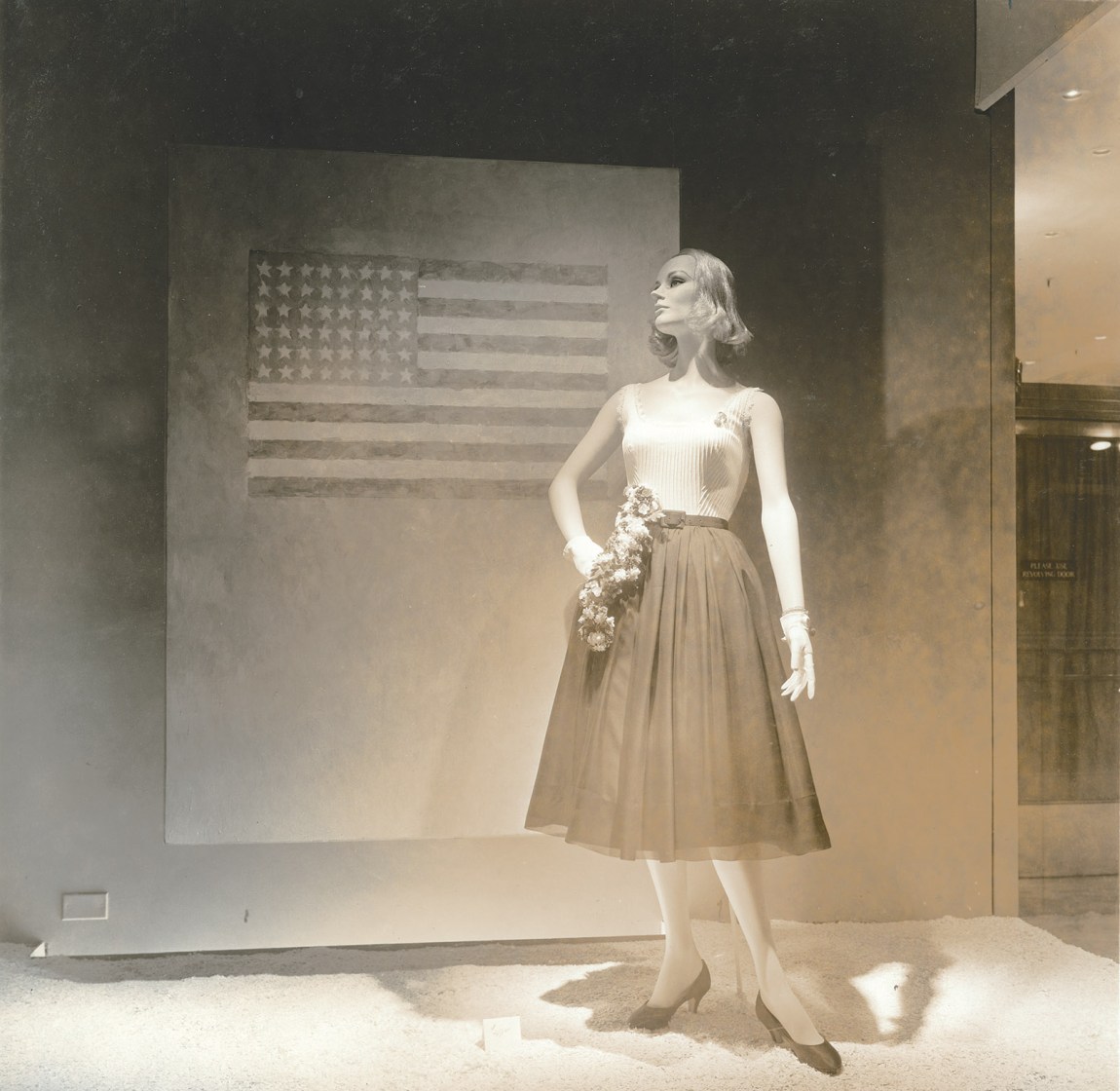

Weird Americans winning lucrative prizes was part of a much bigger game. One of the things that characterizes American art in the years that Menand illuminates with such dazzling erudition and stylistic brio is the way the borders between commerce and art became fuzzy. This is not only about the way certain impoverished outsiders became rich and famous as an industry of critics, producers, publishers, and gallerists assigned cultural—and therefore monetary—value to their work. It was also a matter of ideology. The new generation of American artists began to think of advertising and commercial imagery as the real avant-garde. Mass audiences, they realized, had learned to accept the outré as everyday, long before the critics descended to validate it. Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns worked as window dressers for the high-end New York department store Bonwit Teller (later demolished to make way for Trump Tower). There is a photograph of Johns’s groundbreaking painting Flag on Orange Field as the backdrop to a Bonwit’s mannequin display in 1957 (see illustration above).

Advertisement

That was some months before the painting featured in Johns’s first show at the Castelli Gallery in January 1958, where, Menand writes, along with his other signature paintings of flags and targets, it “rocked the art world.” Presumably hundreds of thousands of people had glimpsed, in the store window, the painted image of an American flag against a background that might be a blown-up detail of an Impressionist landscape, and apparently they survived without having their minds blown. But reframed as a challenging cultural object, it was suddenly sensational. Johns the decorator was now Johns the artist. MoMA bought four works from that show by this previously unknown painter, making him an instant star. “It was,” the critic Hilton Kramer said later, “like a gunshot. It commanded everybody’s attention.” Andy Warhol, likewise, created window displays for Bonwit’s and was a highly successful commercial artist long before his soup can paintings placed him on the cutting edge of the art world in 1962. This was less a matter of art being commercialized than of commercial culture being aestheticized.

The fuse for the explosion of Pop Art in the US in 1962 had been lit in postwar Europe. Younger artists in the dreary, austere Britain of the early 1950s began to reject the modernist disdain for the garish hucksterism of capitalist salesmanship. As Menand writes of Eduardo Paolozzi, Richard Hamilton, and the theorists who helped to shape their discourse, Reyner Banham and Lawrence Alloway, “they did not see consumerism as a blight. They saw it as a stimulus, a source of pleasure, an antidote to insularity—the future.” This was especially true of American consumerism. In 1969 Banham recalled the British art of a decade earlier:

How salutary a corrective to the sloppy provincialism of most London art of ten years ago US design could be. The gusto and professionalism of widescreen movies or Detroit car-styling was a constant reproach…. To anyone with a scrap of sensibility or an eye for technique, the average Playtex or Maidenform ad in American Vogue was an instant deflater of the reputations of most artists then in Arts Council vogue.

Hamilton articulated in 1957 the idea of Pop Art as an aesthetic that aspired to the condition of the consumer product. He listed the qualities it should have: popular, transient, expendable, gimmicky, glamorous, and—he used the term explicitly—big business. Such a frank alliance between avant-garde art and capitalism was made possible by the cold war. The rivalry with communism gave consumerism an appearance of depth. It was not, as elitist critics had long maintained, shallow and meretricious. Consumerism stood for what Harry Truman called, in the 1947 speech that inaugurated the cold war, a “way of life.” Communism imposed everything from above. But capitalism—in its own self-image—created infinite choice. Its claim (seldom borne out in reality) was that it allowed the consumer to make all the decisions. Coke or Pepsi, Gillette or Wilkinson Sword, Max Factor or Revlon—it’s entirely up to you. And that is what makes America, and by extension its allies in the Western bloc, distinctive from and better than its Communist rivals.

The same idea was at the heart of the American artistic revolution of the 1950s. The customer is king. It is not the artist but the viewer, listener, reader, or audience member who creates the meaning of the work. The aim of aesthetic creation is to make the producer disappear and leave only the object and the consumer. This was not a new idea. In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce’s budding writer Stephen Dedalus decrees that “the artist, like the God of creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails.” Marcel Duchamp, a hero to Cage and the adoptive grandfather of the Pop artists, based his creations on the belief that (as Menand puts it) “the artist doesn’t make the paintings signify; the viewer does…. The art object itself is empty, inert; it is ‘made’ by the spectator.” But what placed these ideas in the center rather than on the periphery in the 1950s and 1960s was the way they dovetailed with the ideologies of both consumerism (the product is “made” by the buyer) and the cold war (this power of individual choice is what makes us better than them).

Advertisement

In some respects, this idea was wonderfully democratic. Internally, within the work, it proposed a strict equality among all its constitutive elements. None was supposed to dominate the others. Externally, in the relationship between art and audience, its basic gesture was an apparent humility. Shelley had claimed that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world”; now the artists would resign from office and renounce all claims to set the rules even for how their own work must be experienced. If you look at a Jackson Pollock painting, you don’t know where to focus—the picture has no visual center around which it is organized. In a Rauschenberg combine there is no signal as to which bit matters more than any other. Cunningham decided likewise that a dance did not have to be choreographed around a single point: every angle from which it could be viewed was the “front.”

Cage’s music took to extremes the logic of Arnold Schoenberg’s abandonment of the tonic—the original key of a composition toward which all dissonance must resolve itself. He essentially dismissed the entire European tradition as a kind of musical fascism, in which the composer acted as dictator. Emancipation from the tonic was merely a first step toward emancipation from this imposition of one person’s intention on the musical experience. He scolded his listeners in Darmstadt on the European failure to include enough silence: “When silence, generally speaking, is not in evidence, the will of the composer is.” In his vocabulary (drawn largely from Zen Buddhism), will is a very bad thing. Hence the systematic incorporation of games of chance into the process of creation. Chance negated volition.

It is easy to appreciate the power of this gesture, especially for those who—like so many making the art and creating the critical setting in which it was to be received—were Jewish or gay or both. Nazism was, as suggested in the title of Leni Riefenstahl’s notorious film of the Nuremberg rally, the triumph of the will. For Cage and his contemporaries, the triumph of the unwilled was a kind of reply.

If one were to imagine the precise opposite of the Nuremberg rally, it would be Theatre Piece No. 1, staged at Black Mountain in 1952. Rauschenberg’s White Paintings series was suspended at different angles above the audience. Cage stood on a ladder delivering a lecture punctuated by long silences. His longtime collaborator David Tudor played a piano. Rauschenberg operated an old-fashioned phonograph. Cunningham and other dancers moved through and around the audience. A movie was being projected at one end of the hall, slides at the other. Many of these things were happening at once, the duration of each element determined, of course, by chance. There was no stage, no focal point, no best seats in the house. The experience was made by each viewer’s decisions, from moment to moment, about what did or did not merit attention, which is why such a pivotal event lacks an uncontested record of what occurred. “That,” as Menand notes, “was the intention”—though it might be more apt to say “non-intention.”

The open artwork was a correlative of the open society. It seemed to topple the hierarchical relationship of artist to audience, to take power away from the all-seeing, all-knowing creator and give it to the ordinary, anonymous viewer, reader, or listener. But that is not the way it all worked out. The logic of this broad movement was that the artist would indeed be refined out of existence. If the work is really “made” by the consumer, why do we even need to know who provided the pretext for those repeated acts of creation? Why should we say that 4’33” is “by John Cage” or that a stuffed Angora goat becomes, when a car tire is placed around its middle, a piece “by Robert Rauschenberg”?

Why are they not really by “anonymous,” which is to say every one of us, as we constitute them for ourselves? Because the hierarchy is quickly reestablished. The dominant point of view does not disappear—it merely shifts from inside the artwork to outside, to the vast apparatus of criticism and promotion and institutionalization. Just as the choice between one brand of lipstick and another is not made in a vacuum of influence and power, the ideal of the cultural consumer as a free agent is illusory.

Menand’s great achievement in The Free World lies not so much in his brilliant descriptions and pithy but profound analyses of individual artists and thinkers as in his even more remarkable conjuring of the postwar American “art world.” He cites Howard Becker’s definition of the term: “Art worlds consist of all the people whose activities are necessary to the production of the characteristic works which that world, and perhaps others as well, define as art.”

This last phrase is important. A large part of what is going on in the 1950s and 1960s is defining the “something” that is “happening here” as art—even (perhaps especially) for the baffled Mr. Jones. Why is Cage’s Theatre Piece No. 1 a historic moment in the history of American culture while his appearance on Lascia o Raddoppia? (which sounds like a lot more fun) is not? Because one happened at a liberal arts college famous as a cradle of cultural movements and the other happened on a TV show that was, by definition, light entertainment. But also because the former produced a commodity that was deemed to have permanent cultural and monetary value.

The White Paintings that were suspended from the ceiling at Black Mountain now hang on the walls of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, their blankness filled not with the autonomous perceptions of the viewer but with the thought: This is a Rauschenberg. These acts of definition are performed by the thinkers who shape the intellectual climate; the critics who adopt this or that artist as an exemplar of their own theories; the dealers who package, promote, show, and sell the work; and the museum curators and private collectors who buy it. Without them, there would have been no American art world in which Johns’s Flag on Orange Field could be understood as a high-status cultural artifact rather than a piece of window dressing. But with them, the dream of a nonhierarchical art in which consumers make their own choices was impossible.

The great irony of this period is that not only do radical artists not disappear into their works—they become stars. In the very act of abdication, they are enthroned. Overnight celebrity is, for them, a common fate. Consumerism depends on branding, and the artists were American brands. Warhol cleverly closed the loop by making paintings from celebrity images and brand logos, but others were drawn into it less knowingly. The coincidence in 1957 of the unsuccessful prosecution of the owner and manager of City Lights Books for publishing and selling Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and the appearance of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road produced the Beat Generation. It didn’t much matter that the term was more a punching bag than a useful container. The reliably hysterical Norman Podhoretz asked rhetorically in Esquire, “Isn’t the Beat Generation a conspiracy to overthrow civilization…and to replace it…by the world of the adolescent street gang?”

Nor did it matter much that Kerouac was, as Menand has it, “not a macho anti-aesthete” but “a poet and a failed mystic.” Fame and infamy were as indistinguishable as, in Podhoretz’s rhetoric, criticism and unintentional comedy had become. Once the Beat gang tattoo had been etched on them, Kerouac and Ginsberg were Marlon Brando in The Wild One and James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause.

At the heart of the self-image of the West in the cold war was a powerful but often amorphous idea: freedom. It was, where art was concerned, deeply contradictory. On the one hand, “freedom” was innately oppositional: the “free world” was defined by contrast to the oppressions of fascism that had come before and to the threat of communism it subsequently faced. These two political terrors were fused, under the influence of Hannah Arendt, into a single dark force: totalitarianism. Yet the beauty of this highly political construction of freedom as the defining virtue of the Western world was that it could also be considered as freedom from politics. It could fuse with a notion of art as pure form, liberated from the tyranny of content. “I want images to free themselves from me,” said Johns. “I simply want the object to be free.” His transformation of the American flag—the most crudely obvious political symbol one could imagine—into a purely visual code is emblematic of a much larger attempt to define the aesthetic realm as an entirely autonomous world.

As a reaction against the brutal annexation of the cultural sphere by fascism, Nazism, and Stalinism, the assertion of this autonomy was both necessary and exciting. It drew on the brilliant flowering of formalist thinking in Europe: the “practical criticism” of I.A. Richards in England, the structuralist anthropology of Claude Lévi-Strauss, the linguistic analytics of the Russian émigré Roman Jakobson, and ultimately the deconstructionist theories of Jacques Derrida. This gave it the feeling of being transatlantic without being merely an intellectual expression of cold war divisions. The methodologies of what came to be called New Criticism in the US had a rigor and meticulousness that acted as ballast to the playfulness and apparent randomness of much of the new American art.

Yet the way in which these new ideas were imported into American intellectual life was itself highly political. It was driven, in part, by the institutionalization of literary criticism in the English departments of rapidly expanding universities. Menand observes that for teachers in search of a distinctive professional ethic, the idea of the text as a sovereign realm that generated its own laws and meanings, free from such crudities as biography, authorial intent, or topical meaning, “validated academic criticism itself, replacing the man or woman of letters with the professor as the voice of critical authority.”

Formalist criticism also had the advantage of keeping awkward histories at bay. The central figure in the Americanization of Derrida’s thought, Paul de Man, had a secret past as a Nazi propagandist in Belgium. New Criticism was created in the Old South by a coterie of thinkers known as the Southern Agrarians—Cleanth Brooks, John Crowe Ransom, Donald Davidson, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren—who shared a nostalgia for its lost world and a hatred of northern industrial modernity. Warren, for example, wrote that the “Southern negro” could find only “in agricultural and domestic pursuits the happiness that his good nature and easy ways incline him to.” Menand shows how, as the Agrarians moved into influential positions in northern universities, all of them except Davidson, who remained a very public and active white supremacist, “detached themselves from politics” and “largely shed or buried their political pasts.” The apparent depoliticization of American criticism in this era was not solely an act of evasion, but it is easy to see how much comfort it gave to those who had a great deal to evade.

What, in any case, was freedom, and to whom did it belong? The desire for the art object to be free came easily enough to artists who were male and white. Menand points out that the intellectual and artistic world of the 1950s was even more hostile to women than that of the 1920s. In 1920, 20 percent of Ph.D.s were awarded to women and 47 percent of college students were female; in 1963 the equivalent proportions were 11 percent and 38 percent. Women had a large influence on the creation of the art world as gallerists, curators, and editors, but the avant-garde they promoted was essentially a boys’ club. When MoMA sent its showcase exhibition “The New American Painting” on tour to Europe in 1958, just one of the seventeen painters (Grace Hartigan) was a woman. At a dinner attended in 1951 by Hartigan and Lee Krasner, the vastly influential critic Clement Greenberg was not embarrassed to launch into what Hartigan called “his kick” about why women painters were not very good.

Menand, oddly, barely mentions one of the great avant-garde movements of the era, the astonishing development of post-bop jazz. But he uses the careers of Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, and James Baldwin to explore the tensions within Black writers as they tried to figure out whether the “free world” could ever be theirs. One aspect of that question was whether the broadly constituted American art world of the 1950s and early 1960s was one they wanted to belong to. This, too, was a question of definition. That cultural nexus had managed to assert that the artist was free, that having a point of view within an artwork was a bad thing, that everything in the work of art had equal value, and that biographical experience was irrelevant. To say that none of those supposed truths could apply to most Black artists would be an understatement. Baldwin was, for a time, a successful contestant in the great game show, winning, in 1963, the jackpot of having his face on the cover of Time. But in 1973 Time turned down a piece by Henry Louis Gates based on interviews with him. Gates was informed that Baldwin was “passé.” Even for the most successful Black writer of the period, a place in the official cultural constellation was temporary, uncomfortable, and easily occluded.

The composer Morton Feldman said, “What was great about the fifties was that for one brief moment—maybe, say, six weeks—nobody understood art. That’s why it all happened.” Menand shows how such a vacuum was created but also how quickly it was filled, not just with understanding but with marketing, mythologies, and moneymaking. The Free World is, deliciously, a great rebuke to the cold war ideology of rugged individualism. Its artists and thinkers are always embroiled in the means of production, distribution, and exchange.

Menand’s wit, precision, and skepticism are deployed at every turn to puncture pretensions and cut through all the accreted clichés. One feels sure that he could name, if asked, the twenty-four white-spored mushrooms. But for all his mastery of fine detail, his eyes are always scanning the horizon for power—who has it and how it is being used. And yet his book is never merely cynical. Like a great novelist, he creates a world. Even as he deletes so ruthlessly the self-serving adjective “free,” he fills the noun of his title with tumult and energy, with chaos and creation. This world is not so brave, but it is new, and Menand leaves room for us to wonder that it has such people in it.

This Issue

July 22, 2021

Murder Is My Business

Confrontation in Colombia