If I had to nominate an ideal poet, a Platonic poet, a conservator and repository of poet DNA, a poet to take after and on and from, a forsake-all-others-save-only-X poet, it wouldn’t be Byron, though it would be close. It wouldn’t be MacNeice, though ditto. It wouldn’t be Mandelstam or Akhmatova or Cavafy or Apollinaire or Ovid or Brecht or Li Bai or Bishop or Baudelaire or Les Murray or T.E. Hulme. It would be Heine. Harry or Heinrich or Henri Heine, to taste. Oscar Wilde’s older Parisian cemetery-mate Heine (1797 (?)–1856). Of those named he has perhaps the least presence in English, though it’s a strange thing to say of someone who has furnished three thousand composers with the lyrics for ten thousand lieder, who in his younger years was a bit of a scapegrace, and who for a time after his death was one of the unlikeliest and most hideously travestied of Victorian bards (more even than Shelley—isn’t it all birds and flowers?!), pirated translations of whom were made in the US, of all places.

Here’s why. A life brief, but not exquisitely so; rich in drama, but not stupidly so. Exile, first accidentally—he happened to be in Paris at the end of the Europe-wide round of disturbances in 1830—then permanently: he didn’t want to leave. As happy there as a fish in water. So happy, he said, that he wanted a happy fish to say, “As happy as Heine in Paris.” Heine makes one think that maybe Gertrude Stein—fellow Parisian, fellow fish—was wrong with her remark about remarks not being literature. Maybe that’s exactly what remarks are or literature is—certainly Heine’s, who described the Bible as ein portatives Vaterland (a portable Fatherland) to the Jews, and whose most famous utterance is to do with the burning of books being a prelude to the burning of people. Something as important as a book—or the Book—can live again as a phrase or in a phrase. He is an irresistibly quotable writer, the godfather of the soundbite. And also—because that would just be tedious—he’s the opposite: a relaxed and expansive improviser, who even in his rhymed lyrics sounds as natural as though he’s talking to you.

Then trouble. Ten duels trouble. Trouble given and trouble taken. Nothing in his life that gave him ease and pleasure wasn’t also a source of anguish: family, friendship, career, fame, body. His millionaire uncle, the banker and philanthropist Salomon Heine, ended his stipend; his publisher, Julius Campe, wouldn’t answer his letters for three years; throughout most of the three dozen statelets of pre-unified Germany most of his books were banned for most of his life. And then the long matter of his dying. Syphilis, possibly, or spinal meningitis, at any rate a mysterious, protracted, and agonizing condition kept him confined to bed for seven years (Heine referred to his Matratzengruft, or “mattress-grave”). Among his symptoms were blindness, paralysis, a weight of just seventy pounds, excruciating spinal pain—made endurable only by opium taken three ways, including poured into wounds kept open for the purpose. Opium and the late poems, “Mad revels of a spectral play—/Often the poet’s lifeless hand/Will try to write them down next day,” once frowned on because they were so close to the unmentionable—the body, morbidity—now revered for the same reason.

Knew, it sometimes seems, the whole of the nineteenth century: was taught at university by Schlegel and Hegel; in Paris befriended on the one hand the banker James Rothschild and on the other the yet unbearded Karl Marx; the composers Berlioz and Liszt and Rossini and Meyerbeer; and a whole galère of French writers, of whom he thought little or nothing, among them Balzac, Dumas, Hugo, Sand, Nerval, and Musset. For an exile, he was perhaps without rival in the degree of his integration into the local establishment. Faced, as so often, two ways. The great German literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki once observed, “His true element was ambivalence, albeit not of a sort that resembled conciliatoriness or dither. It was a militant and aggressive ambivalence. He was a genius of love-hate.” A remittance man and one of the first professional freelance writers. Qualified lawyer and once aspiring academic and utterly unemployable. City dweller and enthusiastic sea-swimmer. Devoted son and brother and black sheep of the family. And so on. “And in the wars of gods,” he proclaimed, “I now take the side of the defeated gods,” which might be Jehovah, Jupiter, or Napoleon Bonaparte. Or none of the above.

Jewish German Protestant Royalist Revolutionary Frenchman, buried—without benefit of clergy—in the Catholic part of the cemetery, so that his much younger and devoutly Catholic wife could join him in her own time. (She did, in 1883.) In a lovely late poem called “Gedächtnisfeier,” or “Memorial Service,” he imagines her dolefully visiting his grave (sighing, “Pauvre homme!”), and, knowing her, and considering her pleasure, urges her to take a cab back and the weight off her feet: “Süsses, dickes Kind, du darfst/Nicht zu Fuss nach Hause gehen;/An dem Barrieregitter/Siehst du die Fiaker stehen.” (Sweet fat child, you mustn’t walk home;/You’ll see the cabs standing at the gate.)

Advertisement

Explained Germany to the French, and France to the Germans. Productive. In poetry and prose. Often published together between one set of covers, it being the case that books over 320 pages were not automatically packed off to the censor (touching: the German faith in the purifying quality of drudgery). Heine espoused a kind of swerving prose that unpredictably changed subjects; a master both of contraction and expansion, spinning entire scenes of fictitious dialogue. He was arraigned by the inveterate scold Karl Kraus for having made possible the feuilleton and “so loosened the corset on the German language that today every salesclerk can finger her breasts”; he pioneered travel writing that had little to do with travel; collected work under the title “Salon” (derived from the Salon d’Automne, the annual exhibition of painting in Paris), which could be anything at all; made a polemic on the deceased revolutionary Ludwig Börne, one of whose five sections was about the North Sea. He collected poems under the title “Ollea”—the Spanish olla podrida, a casserole or, literally, rotten pot. An all-sorts.

Poems, then, both amorous and polemical, or polyamorous and amical. The teasing sequence “Sundry Women” names their—made-up—names: “Seraphine,” “Hortense,” “Yolante and Marie,” “Clarisse.” Balladry and intimacy. Politically committed and sagaciously detached. (I don’t know what he would have thought of “writing the revolution,” the subtitle of George Prochnik’s new biography, as a sole ascription; presumably, he would have reversed it, “revolting writer”; thereafter scoffed.) At different times, a democrat and a royalist. As Reich-Ranicki said: ambivalent. It was important not to be bound, ergo he levitated, an ability beyond all but a very few German writers, who were accordingly reviled or at least distrusted—Brecht, I think, Enzensberger, and certainly Joseph Roth, who strikes me now as nothing more or less than Heine redivivus, a recurrence a hundred years later: Jew, cosmopolitan, charismatic exile, politically engaged, a great hater, Paris, money worries, a long malady, imperturbable, crystalline stylist, until one thinks: Is there anything in Roth that wasn’t Heine?

Heine: a liveliness and invention in the writing that can make one suddenly bark with laughter at a rhyme or formulation, now, the better part of two centuries later. An anagram he made of his name and birthplace, “Harry Heine. Duesseldorff,” and by which he signed some juvenile poems, is beyond price: “Sy. Freudhold Riesenharf.” Translated into Pynchonese, it might be something like Simeon Joyluck Harpoon, emanating both anti-Jewish and anti-German ridicule and a tremendous if unspecified erotic threat. Scintillations—not a word of a lie—from the Prose Works of Heinrich Heine: the title of a volume first published in 1873. “He possessed that divine malice without which I cannot imagine perfection,” Nietzsche wrote in Ecce Homo, while Pound’s idol Théophile Gautier called him “a mixture of Apollo and Mephisto.”

A figure with so much specific gravity that people wrote Heine knock-off poems to try to insinuate themselves into his oeuvre; that his family tried to buy his silence; that long after his death, some of his papers were offered for sale to the son of the Austrian arch-conservative Prince Metternich (the driving force behind the Vienna Congress of 1815, the post-Napoleonic settlement of the continent, and hence the man who more than any other forced Heine into exile and kept him there); sale, presumably, for catch-and-kill purposes; that the mostly whimsical, then mostly grave outlines of his life were able to accommodate such apocrypha as that he was born into the nascent nineteenth century, not the waning eighteenth; that his dying words were “Dieu me pardonnera; c’est son métier” (sadly, it was neither Heine nor Voltaire who said that, though both, in the hereafter, are presumably still pretty cut up about it—there is esprit d’escalier and envy even in heaven); that Flaubert was moved, twenty years after the fact, to write, “And I think with bitterness that Heine’s funeral was attended by nine persons! O reading public! O bourgeoisie! Miserable knaves!” when in fact the attendance seems to have been a perfectly respectable hundred or so.

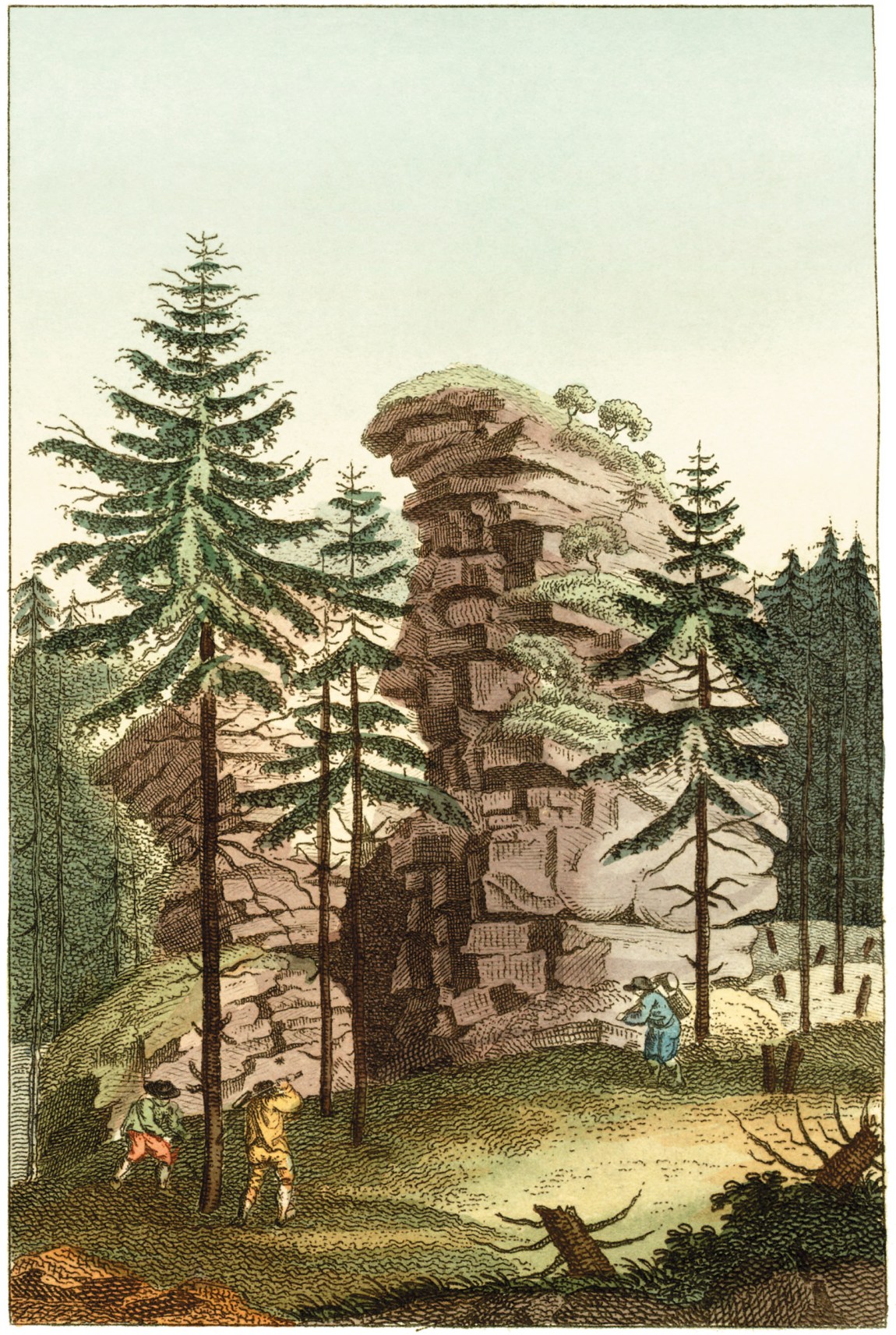

You never go very far in Heine without something concrete, some quiddity. Often it’s done to ironic purpose, a reminder, a bringing down to earth. “The world is stupid and insipid and unpleasant and smells of dried violets” is a characteristic and brilliant instance. It brings genius to jiltedness. During a deadly cholera epidemic in Paris, having discussed what fantastical steps others were taking to stay safe, Heine wrote, “I believe in flannel.” The opening sentence of his first major prose publication, The Harz Journey, his 1824 travelogue on walking in the Harz Mountains, begins and ends with stuff:

Advertisement

The town of Göttingen, famous for its sausages and university, belongs to the King of Hanover, and contains 999 hearths, sundry churches, a lying-in hospital, an observatory, a lock-up, a library, and a beer-cellar, where the beer is very good.

(The translation is Ritchie Robertson’s, and comes from the Penguin volume The Harz Journey and Selected Prose.) This thinginess, this materiality, is part of what makes Heine so modern, such that the critic E.M. Butler called him “the first lyrical realist,” and Thomas Mann’s Francophile older brother Heinrich “the anticipation of modern man.” We tend to think it’s only in the twentieth century that we get Brecht with his poster declaring “truth is concrete,” and Pound talking about images, and Eliot playing games in the mud with garlic and sapphires. In fact, it’s all there in Heine.

When his father apprenticed him as an ornery teenager to a grocery shop and then a bank in Frankfurt, his account of the experience goes: “This was when I learned how to write out a banker’s draft and identify a nutmeg.” There is something—as Heine very well knows—inherently comic in the droll conflation of his duties. His use of balance and pairings is, as often, destabilizing. We see the bankers counting out their nutmegs, the grocers drawing strings of zeroes on brown paper. Later, when his father died—Heine referred to him as “the person whom I loved more than anyone else on this earth”—he wrote to a friend:

Yes, yes, they talk about seeing him again in transfigured form. What use is that to me? I know him in his old brown frock-coat, and that’s how I want to see him again. That’s how he sat at the table, salt-cellar and pepper-pot in front of him, one on the right and the other on the left, and if the pepper-pot happened to be on the right and the salt-cellar on the left, he turned them round again. I know him in his brown frock-coat, and that’s how I want to see him again.

We think perhaps Williams or Lowell (with his “old white china doorknobs, sad,/slight, useless things to calm the mad”) brought this level of humble detail into poetry, and Cheever or Salinger (via Balzac and Flaubert) into prose, but it’s all in Heine. When he wouldn’t call his wife Crescence Mirat by her given name, it wasn’t for any reason of Shavian reinvention (Pygmalion) or sinister masculinist domination; it was because the guttural r’s roughed up his throat to say them. He called her Mathilde instead. A materialist.

It’s no different in poetry. It makes no odds whether it’s the romantic frippery of the Buch der Lieder or the more substantive dissatisfactions of the later poems:

Dearest friend, you are in love,

Though you never have confessed.

Why, I see your heart on fire

Burning a hole right through your vest!

This pokes fun at the tired literary trope—call it the “Corazon”—much as John Berryman would a hundred and something years later: “trapped in my rib-cage something throes and aches.” The poem “Zur Beruhigung” (“Consolation”) tips its quartets with bathos as it relays Heine’s reliable disappointment with German politics. Here are two of its stanzas, again in Hal Draper’s heroic if diminished 1982 Complete Poems of Heinrich Heine (eccentrically published in Boston by the German firm of Suhrkamp, and probably more easily come upon these days in Germany, but which I still had the devil of a job finding):

No Romans are we; we drink our beer.

Each people to its own taste, it’s clear.

Each people is great in its own way;

Swabian dumplings are best, they say.

And:

We always call them our Fathers, and

We call their country our Fatherland,

This ancestral estate where princes sprout.

We also love sausage and sauerkraut.

It’s not that Heine frowns on such plebeian tastes; it’s that he mocks his own foolishness as a political philosopher for expecting more sensational initiatives, something more along the lines of a regicide, from such a docile, phlegmatic population.

The last line of one of the “mattress-grave” poems, “Mein Tag War Heiter” (My Day Was Happy), goes, in Robert Lowell’s cartoon translation in “Heine Dying in Paris” from Imitations—but still responding to something in the original, almost as though the words had dreamed themselves into English: midsummer—in diesem; frail—traulich; green-juice—süßen; bird’s nest—Erdenneste.

midsummer’s frail and green-juice bird’s-nest

in diesem traulich süßen Erdenneste

A literal translation might read, “in this sweetly familiar earth-nest.” The reason Lowell’s phrasing is so odd is that he so reflexively goes off into vocabulary. He habitually has an orchestra to play with. Lowell uses words almost as a fingerprint, an identity giver; “green-juice” is strictly one-off.

Heine’s vocabulary—though divided, ambivalent, like everything about him—seems small by comparison. The same words keep recurring. There is a striking paucity of adjectives: fein, rein, heiter, hold, schön, lieb, fröhlich, glücklich, grob, klug, arm. These words are then reused, especially in the post- or meta-folk style of the Buch der Lieder, where they are deliberately chimed like the notes of a glockenspiel: “Ihr goldenes Geschmeide blitzet,/Sie kämmt ihr goldenes Haar” (her golden necklace glitters/she combs her golden hair) or “der Menschenhäuser und der Menschenherzen” (of human homes and human hearts) or “Weiß das Gewand und weiß das Angesicht” (the robe was white and white the face) or “Und saßest fremd unter fremden Leuten” (and were seated a stranger among strangers). It’s almost a kind of comfort language, the words you find embroidered in a sewing primer. Home Sweet Home. Diminutives are a kind of addiction, almost an obsession, in this often tender speech, especially in his early work—Liebchen, Liedchen, Kindchen, Schätzchen, Blümlein, Äuglein, Bächlein, Töchterlein, Büchlein, Schifflein—but in the late as well (“Der Scheidende,” “The Parting One”):

Der Vorhang fällt, das Stück ist aus,

Und gähnend wandelt jetzt nach Haus

Mein liebes deutsches Publikum,

die guten Leutchen sind nicht dumm.

Peter Branscombe’s accurate subscript crib—yet another way in—from the 1967 Penguin Heine has: “The curtain falls, the play is over, and my dear German public is now going home yawning, the good folks aren’t stupid.” (This is given, quite grotesquely, by Lowell as “my dear German public is goosestepping home,” where it’s not so much the naughty neon solecism of “goosestepping” as the violation of Heine’s indescribably complex and stable tone; as with the beer and sausages earlier, there’s almost a note of envy of such people. “Tragic sense of difference” might perhaps cover it, a pairing of respect and disrespect, irony and affection—but certainly no disjunction or separation, and nothing so straightforward as a sneer.)

Of course, it wouldn’t be Heine if there weren’t also the opposite—a smattering of strikingly learned, original, improvised terms, portmanteau words, classical imports, neologisms: Prachthotel (splendidhotel); Kunstgenuss (artenjoyment); Frühlingsschnurrbart (springmustache); sonnenvergnügt (sunenjoyed); herzbeweglich (heartmobile); Erschiessliches (shootable); Weltposaune (worldtrombone); Erdpechpflaster (earthpitchplaster); Erdenkuddelmuddel (earthhiggledypiggledyness). There is a materiality, a sophistication—as well as a good humor—to these words that makes me think that, had Pound known Heine better (he uses his distich, “Aus meinen großen Schmerzen/Mach ich die kleinen Lieder,” “From my great sorrows/I make my little songs,” as an epigraph for his poem “The Bellaires”), he might have found a more plausible peg for his elusive quality of logopoiea than any he did find. Grosse makes kleine; Lieder, the substantive at the end of the second line, supplants the Schmerzen at the end of the first; they are a pair, but so are meine and kleine. But perhaps most of all, meinen gives way to mach ich, “my” to “I make.” (It’s the secret of how art works.)

Logopoiea, as I understand it, is manipulating the pressure of earnestness or irony in a sentence or phrase. The attempt to get a word to be more than itself, to get above itself or beyond itself, to put spin on it, or wah, or stretch, or reverb, the word that, as Heine says, “ist eitel Dunst und Hauch,” nothing but mist and breath. True. Sometimes. But sometimes it’s more. As in “Die kranke Seele,/Die gottverleugnende, engelverleugnende,/Unselige Seele,” the god-denying, angel-denying, sick, unhappy spirit: the unselige Seele. Or here:

Laura heißt sie! Wie Petrarcha

Kann ich jetzt platonisch schwelgen

In dem Wohllaut dieses Namens—

Weiter hat ers nie gebracht.

“Like Petrarch,” goes Branscombe’s prose literal, “I can now bask platonically in the euphony of this name—he never got any further.” Wohllaut plays—not so platonically—with Laura, while the crashing gebracht (minus one syllable) by suggestion smashes the little “a” at the end of the still more euphonious Petrarcha. In his paean (not really!) to King Ludwig of Bavaria, Heine writes, “Das Volk der Bavaren verehrt in ihm/Den angestammelten König.” Not angestammt, hereditary, ancestral, but angestammelt, someone who comes stuttering up. No wonder the Bavarians had a warrant out for his arrest!

Heine is a rare genius. He changes the nature of German literature and he changes the nature of the nineteenth century. There’s a joyful sophistication in him that none of the English versions is anywhere close to appreciating, much less capturing. Branscombe gives you the sense, and Draper knocks out the rhymes (as I think one must), but it’s a lesser product. Ernst Pawel’s fervent and inward biography, The Poet Dying: Heinrich Heine’s Last Years in Paris (1995), somehow passed me by at the time; it is quite exceptional, and I would recommend it without reservation. Pawel takes time to dish such translations as have been attempted (the French ones being better than the English). I wish someone new would have a go, instead of giving us another Rilke or Trakl or even Celan. Then there’s a wonderful and exhaustive life of the man in German—also available in French—by Jan-Christoph Hauschild and Michael Werner, called Der Zweck des Lebens Ist das Leben Selbst (The Purpose of Life Is Life Itself); it has more pecuniary detail than I have ever seen in any poet’s biography, but with Heine, it serves a certain sense. (He was worried sick for his future widow, who was indeed able to comfortably add to her collection of parrots. He wrote letters to rich men, begging them to send him railway shares.)

George Prochnik’s new study feels short and has a breezy way with it (there’s a very good Goethe joke in it), but it is also full of heavy matter. Its special focus is on the background. It’s clear that to know enough, one has to know a great deal too much. Prochnik gets so bogged down in admittedly complicated circumstances that with fifty pages to go, it’s still only 1831, and Heine isn’t even in Paris. The ending is unsurprisingly desultory. Its themed chapters have the effect of pulling Heine apart, making his life seem like a series of unconnected battlefields, which, God knows, is probably how it felt. On the model of the Harry Potter titles, it would be Heine and the Chosen Antagonist. There’s Heine and his mother, Heine and the Varnhagens, Heine and Judaism, Heine and Saint-Simon, Heine and Marx, Heine and the Feud with Platen, Heine and the Feud with Börne, and so on and so forth. It’s like being given a handful of spindles and cogs and springs fresh out of an oil bath in place of one’s constantly surprising, faithful, reliably ticking wristwatch.