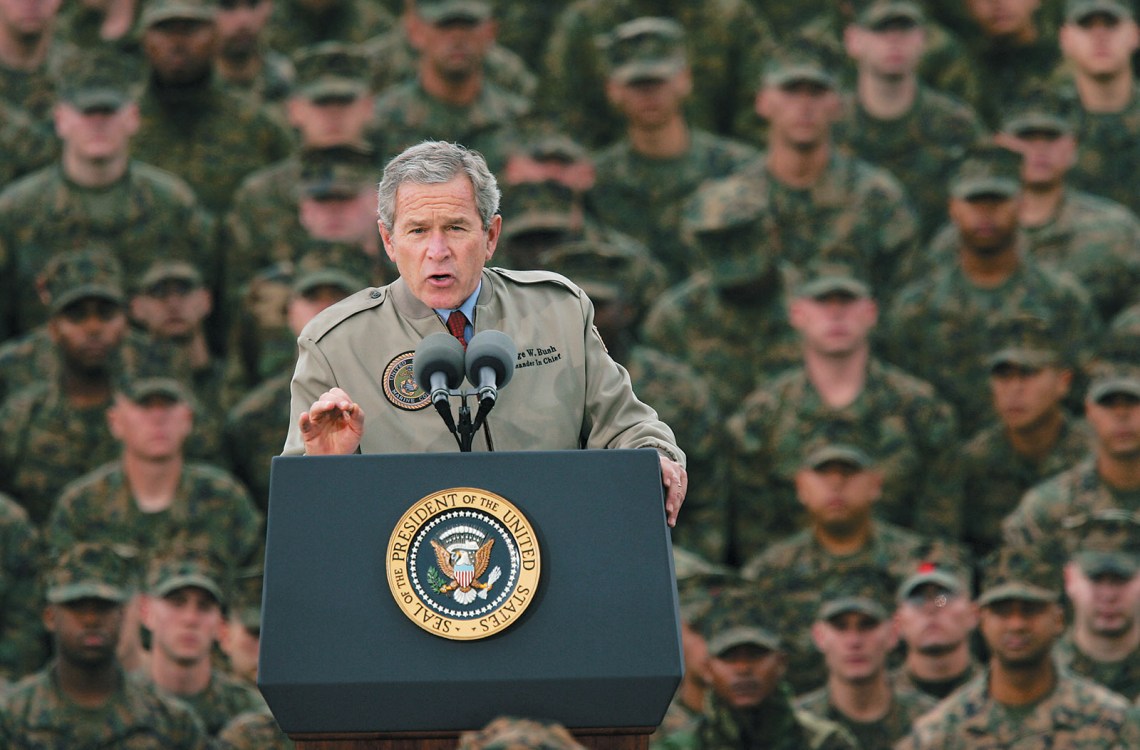

Nearly two decades have passed since President George W. Bush ordered the invasion of Iraq in 2003, arguably the greatest strategic blunder in American history. It led to the deaths of more than 4,400 US military personnel and (according to the research group Iraq Body Count) up to 208,000 Iraqi civilians, to say nothing of the destabilization of the Middle East and the deadly convulsions that followed—sectarian violence, the emergence of ISIS, and a refugee crisis larger than any since World War II, among other calamities. And yet we still don’t understand just why the US went to war.

Conventional wisdom lays the blame on neoconservatives, mainly midlevel officials of the Reagan administration who, in their exile during Bill Clinton’s presidency, founded the Project for a New American Century (PNAC), a think tank that advocated a foreign policy stressing “US preeminence” to “secure and expand the ‘zones of democratic peace’” through, if necessary, the forcible removal of hostile dictators, not least Saddam Hussein.1 “Regime change” in Iraq had been a neocon cause ever since Bush’s father, President George H.W. Bush, stopped short of sending US troops northward to Baghdad after ousting Saddam’s invading army from Kuwait in 1991. Two high-ranking officials in the administration of the younger Bush—Paul Wolfowitz, the deputy secretary of defense, and Lewis “Scooter” Libby, chief of staff to Vice President Dick Cheney—had been prominent figures in the PNAC and, once back in power, pushed its agenda with new fervor.

Bush, who was the governor of Texas before he entered the White House, had no roots in that faction of the Republican Party and no background—or interest—in foreign policy. His national security adviser during his campaign and his first term as president, Condoleezza Rice, was a firm adherent of realpolitik, and she frowned on humanitarian intervention, touted the balance of power among nations as essential to maintaining peace, and had written, in the January/February 2000 issue of Foreign Affairs, that the best way to confront rogue regimes harboring nuclear ambitions—such as Saddam’s—was through “a clear and classical statement of deterrence”: If you nuke us or our allies, we’ll nuke you in response. During one of that year’s election debates, it was the Democratic candidate, Vice President Al Gore, who broadly advocated military intervention to promote freedom and democracy around the world. In pointed contrast, Bush called for a strong but “humble” foreign policy.

Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld were more interested in maintaining American power than in flighty goals of spreading democracy. The two came into office with no special animus toward the Iraqi government. Rumsfeld, as a special envoy for President Reagan, had met Saddam in the early 1980s to discuss their common interests in Iraq’s war against Iran. Cheney, as Bush Sr.’s defense secretary, had defended, perhaps sincerely, the decision not to oust Saddam in 1991. In the first several months of the younger Bush’s presidency, neither Cheney nor Rumsfeld expressed much support for Iraqi regime change—despite memos from Libby and Wolfowitz attempting to rally them to the cause.

The pivot came with the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. There probably wouldn’t have been an invasion of Iraq without the fear and paranoia they aroused: many feared another attack at any moment. But how did Bush and his top advisers come to believe that Saddam, the secular Sunni leader of Iraq, was conspiring with Osama bin Laden and the other fanatical Islamists who attacked the Twin Towers and the Pentagon (a notion derided by intelligence officials as “science fiction”) or that Saddam was developing weapons of mass destruction—nuclear, chemical, and biological—with the possible aim of providing them to al-Qaeda?

This is the main riddle that Robert Draper, a deft political journalist for The New York Times Magazine, aims to solve in To Start a War. Countless scribes before him have posed the same question; none of them unearthed definitive answers. Draper leaves some gaps as well, though he comes closest to unraveling the central mysteries; he even dredges up reams of new information—not only shiny tidbits but fresh insights and revelations.

Draper’s central insight is to place George W. Bush at the center of the action. When it came to invading Iraq, Bush truly turns out to have been “the decider,” as he once described himself. And in those instances when others took charge, his style of decision-making was to let them, whereas most other presidents would have asked questions, mulled the options, perhaps convened a meeting of the National Security Council (NSC) to weigh the pros and cons of a proposal. Draper convincingly shows that, under Bush, there was “no ‘process’ of any kind,” at any stage of the war, from the decision to invade to figuring out how post-Saddam Iraq should be governed.

Advertisement

At some point, Bush decided that “Saddam is a bad guy,” so “we need to take him down,” and the path to war was paved from there. Bush is not among the more than three hundred sources whom Draper says he interviewed for this book (among them roughly seventy intelligence officials), but the two men spent many days together in the late 1990s for a Texas Monthly profile, which evolved into a book-length portrait of Bush, reported and written while he was president, and during that time Draper, a fellow Texan, saw a figure, in formation and in action, that few other journalists glimpsed so close up.2

In the weeks after September 11, many of Bush’s underlings were startled to witness this affable but aimless president—uncertain of himself, uneasy with his legitimacy after losing the popular vote and eking out a thin Electoral College edge thanks to a 5–4 Supreme Court ruling, content to spend half of his time away from Washington clearing brush weeds back at his ranch in Texas—suddenly seized with a “piercing clarity of purpose” and an “unchecked self-confidence.” Draper paints a vivid scene of Bush speaking to a group of Asian journalists in the Oval Office, pointing to portraits of Churchill, Lincoln, and Washington, aligning himself as their peer, and viewing himself as “a leader who knew who he was and who knew what was right.” And one thing he knew, being (as Bush himself put it) “a good versus evil guy,” was that “the time had now come to confront Saddam Hussein.”

It is remarkable—and a central theme in the book—how swiftly so many senior officials fell into line, some of them against their better judgment, for reasons of misguided duty, crass cynicism, or converging motives. Wolfowitz, Libby, and a few other neocons had never pushed for an actual invasion—they fantasized about prodding small bands of Iraqi Shias and dissidents to crush Saddam’s army with the help of US air strikes—but they signed on to it, and took part in the cherry-picking of raw intelligence data that seemed to confirm that Saddam had WMDs and was affiliated with al-Qaeda, as the way to fulfill their dream. (WMDs were, as Wolfowitz later put it, “the one issue that everyone could agree on.”)

Cheney cared nothing about promoting democracy or freeing Iraqis from a brutal dictatorship; still, he eagerly went along, determined to expand American power at the nation’s “unilateral moment” following its cold war victory. Rumsfeld was entranced by the new generation of ultra-accurate “smart bombs” and saw Iraq’s desert as a battlefield laboratory for testing the theory that they “transformed” modern warfare. (His obsession led him to slash the number of troops in the military’s war plan, on the premise that the new weapons made massive ground formations unnecessary. He was right that stripped-down forces were enough to crush the Iraqi army but didn’t consider their woeful inadequacy for securing and stabilizing territory, or even for defending themselves in the insurgency that followed.)

It was CIA director George Tenet who most actively abetted the exaggerations—and fostered the outright lies—that persuaded a majority in Congress, the media, and the public to support the war. It is important to note (and Draper makes this clear) that almost everyone in Bush’s inner circle really believed that Saddam had WMDs—if not nukes, then chemical or biological weapons, which a 1991 UN Security Council resolution banned him from developing. Those types of weapons were certainly within his capacity: he had built them a decade before, even used them in the Iran–Iraq War, but destroyed most of them under UN auspices after the first Gulf War. And there were still widespread suspicions—abetted by Iraq’s efforts to mislead UN weapons inspectors—that some remained hidden and that he could resume production. Even Hans Blix, the head of the international team sent to search Iraq for banned weapons in 2002, who tried to block the rush to war, thought that Saddam must have been hiding something and that, given enough time, his inspectors would find it.

But the intelligence analysts who were most expert in the region and in the technology for making and handling WMDs couldn’t find persuasive evidence to make the case that Saddam had any, and Tenet did what he could to suppress their skepticism. A holdover from the previous administration, he had been frustrated by Bill Clinton’s lack of interest in what the CIA had to offer. For any CIA director, the president is the “First Customer”—the sole source of the agency’s power—and under Clinton that power had dissipated. By contrast Bush, especially after September 11, was riveted by the agency’s reports; he had Tenet personally deliver its Presidential Daily Briefing at 8 AM, six days a week. At last, the CIA had a seat at the big table, and Tenet wasn’t going to blow it.

Advertisement

Midway into 2002, if not sooner, the leading voices in the White House were so keen on going to war—and so invested in all the rationales to make it politically palatable—that an impenetrable groupthink took hold. Draper recounts an emergency meeting among NSC deputies to discuss “Why Iraq Now,” at which a career CIA analyst dissented from the consensus, wondering out loud why Saddam was considered a threat. Libby turned to Doug Feith, a gung-ho Wolfowitz ally in the Pentagon, and asked, “Who is this guy?” As Draper puts it, “They had their case for war, and they were sticking to it.”

Senior officials throughout the national security bureaucracy—Tenet very much among them—inferred from these and other incidents that the decision to invade was a fait accompli and made sure to hop aboard, lest they lose their influence. This “fevered swamp of fear and genuine threat” particularly pervaded Cheney’s office, which Draper calls “the Bush administration’s think tank of the unthinkable.” Tenet went so far as to supply Team Cheney with a “Red Cell”—a group whose job was to invent the scariest scenarios and draw the most far-fetched connect-the-dot conspiracies imaginable in “punchy” three-page memos. (“Our goal,” one of its members said, “was plausibility, not anybody’s notion of truth.”) Cheney, Libby, and Wolfowitz loved its work. (The one question the Red Cell did not ask, Draper notes, was “What if Saddam Hussein did not possess WMD?”)

When the chief of the CIA’s Iraq Operations Group refused to fulfill a request by Cheney’s office to interview a self-described Iraqi insider who was known to be a fabricator, Jami Miscik, the deputy director for intelligence, stormed into the chief’s office and screamed, “You’re not supporting the consumer!” Miscik told another aide that it was “very important” for the consumer—the president and those around him—“to continue to rely on us. As soon as they say ‘To hell with you all,’ you’re lost.” By the time the White House ordered the CIA to produce a National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on the Iraqi threat, the nature of the assignment was clear: as the head of the NIE team wrote to an analyst on his staff, in a memo obtained by Draper, “WE HAVE TO SAY IRAQ HAS WMD”—even though the evidence was sketchy at best.

Internal dissension from this foregone conclusion turns out to have been more widespread than previously reported. It is well known, for instance, that the State Department’s intelligence bureau filed a footnote to the NIE disagreeing with the claim that aluminum tubes found in Iraq could be used to enrich uranium. Draper learned that the analysts in the Department of Energy also wanted to file a dissent—they thought the claim was preposterous—but their political director overruled them.

Probably it didn’t matter, as the report’s executive summary—the only document read in Congress or briefed to Bush—cited none of the dissenting footnotes. This too was to satisfy Bush. He was a man of certitude and confidence, and he wanted intelligence of the same stripe: clear and definitive conclusions, without probabilities or caveats. Once Bush decided that “Saddam is a bad guy” and “we need to take him down,” there wasn’t a serious debate within the NSC on whether an invasion was the best course of action.

But what if there had been a debate? What if, Draper asks, prominent or well-informed insiders had threatened to quit—or had even spoken up in opposition to the war? At one point in July 2002, he reports, a member of the State Department’s Iraq team suggested that the entire staff resign in protest, but their director, Ryan Crocker, who later became the ambassador to Iraq, convinced them that such a move would amount to “a one-day newspaper story” about “a bunch of whiners at State. If you really want to have an impact,” Crocker told his team, “stay and do what good you can”—a rationale commonly invoked by officials who have mulled resigning in protest, then thought otherwise. In this case, as in most other such cases over the decades, they stayed and did what good they could, but had no impact anyway.

The truly tragic figure in this regard, and the one who might have made a difference if he’d spoken up, was Bush’s popular but bureaucratically outmaneuvered secretary of state, Colin Powell. A retired four-star general, Powell had deep misgivings about the war but kept mum about them, seeing himself as a “good soldier,” not the quitting type. Cheney, his constant, more manipulative rival for Bush’s ear, shrewdly recruited Powell—the administration’s most trusted figure among the public, Congress, and America’s allies—to make the case for war to the UN Security Council. Powell spent many nights at Langley going over the script the CIA had prepared, examining the intelligence, tossing out claims that weren’t supported. But in the end, he got steamrolled. As Draper tells it, Tenet had assembled a team of “yea-sayers” to handle Powell’s questions and to quell his doubts. Plenty of CIA analysts doubted the case for war—doubted that Saddam had WMDs or links to al-Qaeda—but they were never brought into the room; Powell didn’t know they existed.

Bush was to blame for this as well: as president he should have wanted to hear from the doubters, if just to say that he’d heard from them. But along with his misplaced single-mindedness, Bush also had what seemed an utter lack of inquisitiveness. When he was given an intelligence brief on August 6, 2001, headlined “Bin Laden Determined to Strike in US,” he asked no follow-up questions. (The specialist who prepared the brief told Draper that he thought to himself, “So what is this—you’re not even curious?”) Even as the post-invasion quagmire deepened, Bush wasn’t interested in learning what had gone wrong. Retiring commanders, summoned to the Oval Office for their farewell debrief, quickly picked up on cues that the president wanted to hear only “good news,” not analysis or suggestions for change.

There was thorough deliberation on one issue: what to do about the remnants of Saddam’s regime after the war was over—specifically whether, or to what extent, to outlaw the ruling Baath Party and to disband the Iraqi army. The question was debated just a week before the invasion at two National Security Council meetings, with Bush, his cabinet secretaries, and top military officers present. The participants unanimously agreed with the conclusions of an NSC staff report: except for the top stratum, Baath members should not be banned from political posts, because most Iraqis had to join the party to get such jobs; and except for Saddam’s elite Republican Guard, the Iraqi army should be kept intact. Several US officers were already circulating brochures urging Iraqi soldiers and commanders to stay in place after the invasion, so they could restore order.

But in mid-May, with Saddam overthrown and on the run, L. Paul “Jerry” Bremer, whom Bush had appointed to head the Coalition Provisional Authority, arrived in Baghdad and issued two orders. The first barred all Baath Party members from holding political positions; the second disbanded the Iraqi army. Bremer announced he was implementing the orders on a video link to an NSC meeting; it was the first that most of those in the room had heard of them. They contravened two presidential decisions, but Bush didn’t care. “You’re our man on the ground,” he told Bremer.

This was the most consequential act of the war, next to the invasion itself. With Iraq’s political elite dismissed from their jobs, anarchy was inevitable. With its armed forces thrown out of work but their access to weapons intact, an armed rebellion was inevitable. And with no swift replacement for Saddam, who’d ruled in part by balancing (as well as oppressing) Iraq’s sectarian tribes, civil war—combined with the other upheavals—was inevitable as well.

Without Bremer’s two orders, there might have been a somewhat orderly post-Saddam politics; insurgency conflicts might have been much less violent and might not have metastasized throughout the region. The genesis of these orders is, even now, not clear. Draper repeats the standard line that the documents were written by Doug Feith and a Pentagon colleague, Walt Slocombe; and that Feith handed the papers to Bremer, telling him to declare them as policy upon arrival in Baghdad. But Feith and Slocombe were midlevel officials, lacking the authority or the nerve to override a presidential decision. Who told them what to write, and who assured them that it was fine to pass the orders on to Bremer?

Draper doesn’t address these questions, but one of the main figures involved must have been the charismatic London banker and Iraqi exile Ahmed Chalabi. This oversight is surprising, since Draper, like most chroniclers of the war, points to Chalabi as a clear villain in many other parts of the story. Though he hadn’t seen his homeland for almost fifty years, Chalabi had long lobbied myriad entities, including US intelligence agencies, to overthrow Saddam, offering himself as a successor who would be supported by a militia that he claimed to be assembling, called the Free Iraqi Forces (FIF). Chalabi had a self-aggrandizing interest in dismantling the Baath Party (which, left intact, would have blocked his ascendancy) and the Iraqi army (which wouldn’t have stepped aside for the FIF).

Chalabi insinuated himself into neocon circles, to the point that Cheney, Wolfowitz, Libby, Feith, and others were, in Draper’s words, “hopelessly smitten,” likening him to de Gaulle; Chalabi in turn fed them phony intel, some of it parroted by later-discredited sources, which reinforced the American marks’ desire for war. (After Saddam fled, Wolfowitz, on his own initiative, arranged for a military plane to fly the so-called leaders of the FIF to Baghdad; they vanished upon arrival.) It is still unknown just how Bremer’s script got written. Did the orders come from Wolfowitz, Libby, or possibly Cheney? Given the less-than-voluminous paper trail left by the Bush White House (according to Draper, no notes were taken during NSC meetings, “so that Bush could feel free to air whatever half-baked or intemperate thing was on his mind”), we may never know the answer.

It didn’t take very long for nearly everyone to know that the war was a disaster and, more than that, a mistake—but no one took the heat. Saddam had no WMDs; the Iraqi weapons programs had been abandoned years before. Some of the more guilt-ridden CIA analysts wrote memos acknowledging that they’d been wrong, but higher-ups blocked their circulation. When Stephen Hadley, Bush’s second national security adviser, learned that a crucial piece of evidence he’d been peddling—purported letters from Iraq to Niger requesting a supply of yellowcake uranium—was a forgery, he offered to resign. But Bush told him to stay. Tenet didn’t merely escape punishment; he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Bush himself suspected that he’d done wrong. Watching a live TV broadcast of allied troops entering the southern Iraqi town of Basra to a glum reception, he turned to Powell, who was watching with him, and asked, “Why aren’t they cheering?” In October, with Iraq clearly falling apart, he turned again to Powell, as they stood waiting for an elevator, and said, “Colin, you warned me.” (Powell had once famously invoked what he called the “Pottery Barn rule” of military interventions: “You break it, you own it.”)

Donald Trump is never mentioned in To Start a War (it’s likely that Draper did most of his work before Trump entered the White House), but it’s hard not to read the book without drawing parallels with our twice-impeached former president. His foibles were similar to Bush’s—the unearned self-confidence, the intense parochialism (“an inability,” as Draper says of Bush, “to understand how the outside world viewed the United States”), the obliviousness to nuance, the demand that subordinates “support the president’s value judgments rather than…question them.” The difference is that, in Trump, these traits were compounded by a prideful ignorance (Bush at least read books and intelligence reports) but mitigated by a lack of appetite for war.

Draper leaves a few mysteries unsolved. For instance, it’s never quite clear where Bush acquired his moral absolutism, at least when it came to Saddam (he didn’t apply it to other dictators), or when his animus toward Saddam took hold. Draper cites the well-known incident when Saddam tried to assassinate Bush’s father; but he also quotes some of his closest aides, including Condi Rice, as saying that before September 11, Bush never obsessed over Saddam.

He also oversimplifies Rumsfeld, presenting him as a man of no serious ideas. For instance, his advocacy of “transformation”—the notion that new technology could win wars with few troops on the ground—is treated as a personal eccentricity, although the idea had been percolating in national security circles for a decade and, by the time Bush took office, had evolved into mainstream Republican consensus. Rumsfeld was particularly influenced on the matter by a veteran Pentagon official named Andrew Marshall, an intellectual Svengali of bureaucratic politics, who goes unmentioned in this book.3

But these are quibbles. Draper’s subtitle is “How the Bush Administration Took America into Iraq.” One might wish that he’d dealt more thoroughly with why, but unless Bush or Cheney left behind secret tapes, this may be the most complete chronicle we ever get. He makes it inescapably clear that the war was no mere well-intentioned tragedy but rather a sequence of deceptions and duplicities that could have been halted at several points along the way, before it led to the hideous disfiguring of American foreign policy and its image in the world for many years to come.

-

1

The PNAC’s first public document, an open letter to President Clinton in January 1998 calling for a “new strategy” aiming, “above all, at the removal of Saddam Hussein’s regime from power,” signed by Wolfowitz among others, is widely viewed as the template for Bush’s later interventionist policy. ↩

-

2

Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush (Free Press, 2007). ↩

-

3

See my Daydream Believers (Wiley, 2008), especially chapter 1. ↩