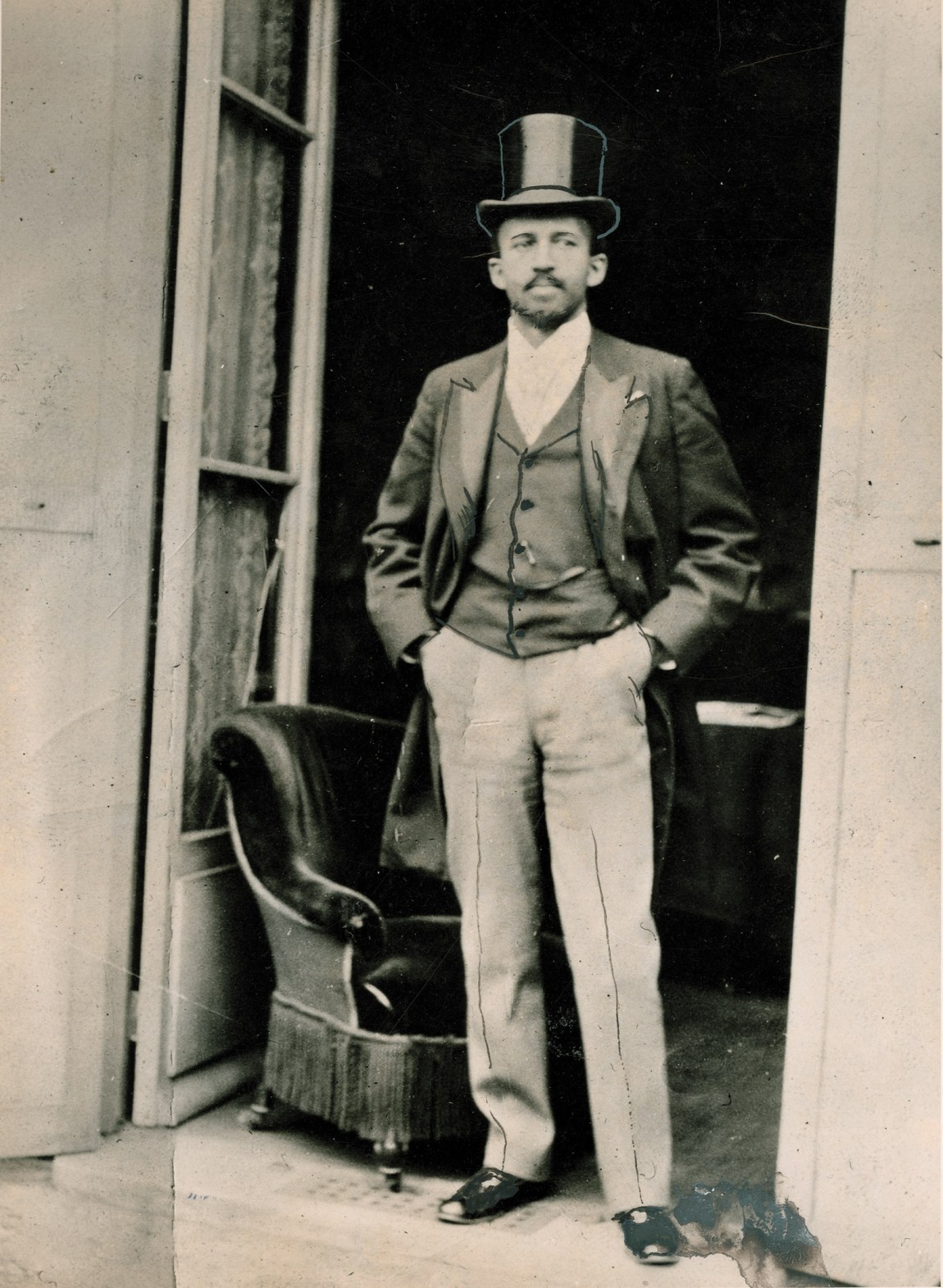

W.E.B. Du Bois carried himself as if he were “the Negro race.” Throughout his very long life—ninety-five years—his personal successes and victories were the successes and victories of all African-Americans. The problems he encountered as a Black man were the problems of Black people the world over. This way of thinking started early. His childhood in New England—Du Bois was born and raised in Great Barrington, Massachusetts—introduced him to the troubled racial dynamics of the United States and to a way of coping with them. In his most acclaimed work, The Souls of Black Folk (1903), Du Bois described both the moment he discovered that he was on the vulnerable side of the racial divide and his response to that realization:

In a wee wooden schoolhouse, something put it into the boys’ and girls’ heads to buy gorgeous visiting-cards—ten cents a package—and exchange. The exchange was merry, till one girl, a tall newcomer, refused my card,—refused it peremptorily, with a glance. Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others; or like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world by a vast veil. I had thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, to creep through; I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in a region of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluest when I could beat my mates at examination-time, or beat them at a foot-race, or even beat their stringy heads.

As he grew older and took note of the “dazzling opportunities” placed before white people, Du Bois decided that he would “wrest” some of those prizes from them. Whatever innate competitiveness he possessed was sharpened and directed by the experience of being treated as different and, on some occasions, as inferior.

In the decades that followed his Great Barrington youth, Du Bois won many of the privileges and honors that the world had seemed to reserve for whites. He went from one scholarly and professional triumph to another—graduating from Fisk University, the University of Berlin, and Harvard University, where he was the first Black person to earn a Ph.D.; becoming one of the founders of a new field, sociology; and in 1909 helping to start a new organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He wrote dozens of articles and books, and edited magazines. He was a walking refutation of the concept of Black inferiority.

Throughout his career, Du Bois believed it was important to find and showcase the accomplishments of other Blacks like him—though, of course, there really was no one, of any race, quite like him. A born scholar, preternaturally disciplined and driven by belief in the power of rationality and evidence, he was convinced, particularly during his early career, that examples of Black achievement would serve as effective answers to the scientific racism that had become ascendant in the nineteenth century. Numbers mattered. Person by person, fact by fact, information about Blacks of ingenuity would put the lie to the doctrine of white supremacy. That talented Blacks managed to excel even in the face of the depredations of Jim Crow and lynching was further proof of the worthiness and genius of the race.

Du Bois also saw early on that the struggle of Black people was global. As he famously wrote, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line,—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.” For Europe, a long and bloody history with people of color had extended from enslavement beginning in the sixteenth century to colonization in the nineteenth and early twentieth, as nations including Great Britain, France, Belgium, and Italy took control of 90 percent of the African continent.

After all of this—because of all this—white supremacy was a worldwide phenomenon, and it had a particular force in the US, home to a large population of people of African descent. How they fit into the American polity was, and remains for many, a contested issue. But Du Bois saw African-Americans as having a unique perspective and message to send as the foremost proponents of the idea of equality embodied in the Declaration of Independence, carrying it forward in the face of open hostility. Their perseverance, faith, and creativity would provide a useful example to the oppressed the world over.

In 1900 Du Bois got the chance to explore some of these ideas on an international stage. That July he participated in the First Pan-African Conference, in London, where he helped draft an open letter to European leaders calling for the right to self-government for Caribbean and African nations and enhanced political rights for African-Americans. He then went on to Paris to oversee an unusual project he had worked on feverishly for months: the “American Negro Exhibit,” which appeared at the 1900 Paris Exposition—the largest world’s fair to date, heralding the arrival of a new century. It was an opportunity to demonstrate to millions of visitors the achievements of US Blacks in the thirty-five years since the end of the Civil War, using modern methods and data from the field he had pioneered.

Advertisement

After the first world’s fair, the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London in 1851, Paris had been the site of four world’s fairs and had become known as the “Queen City of Expositions.” The French were determined to make the Exposition Universelle of 1900 the most impressive of all, allotting 350 acres to it in the center of Paris. Forty countries participated, many of them building their own elaborate pavilions inspired by some famous structure or landmark from their native land, while displays of the countries’ contributions to science, culture, and industry were placed in satellite buildings.

The Americans modeled their pavilion after the US Capitol, and in the Palace of Social Economy and Congresses exhibited information about labor unions, tenement housing in New York, libraries, and industrial regulation. And in one corner was an eye-catching display, set up like a small study, titled “Exposition des Nègres d’Amérique.”

Originally there was no plan to include African-Americans in the US presentation. But two Black men, Daniel Murray, an assistant librarian at the Library of Congress, and Thomas J. Calloway, a lawyer, newspaper editor, and confidant of Booker T. Washington, had realized that the exposition was the perfect venue for showing the world some of the achievements of Black America. Calloway had been a state commissioner for the Atlanta Exposition of 1895, where Washington gave what has come to be called his “Atlanta compromise” speech, in which he suggested, among other things, that Blacks stop agitating for social equality and full voting rights in favor of working for economic self-improvement.

Sensing the opportunity to focus world attention on the situation of Blacks in America, Calloway wrote to prominent Black leaders throughout the country, including Washington and the suffragist Mary Church Terrell, explaining the potential benefits of mounting such an exhibit:

Thousands upon thousands will go [to the fair], and a well selected and prepared exhibit, representing the Negro’s development in his churches, his schools, his homes, his farms, his stores, his professions and pursuits in general will attract attention…and do a great and lasting good in convincing thinking people of the possibilities of the Negro.

Washington was duly impressed with Calloway’s idea. As Linda Barrett Osborne writes in the introduction to A Small Nation of People, David Levering Lewis and Deborah Willis’s book about the “American Negro Exhibit,” he

appealed personally to President William McKinley, and just four months before the opening of the Exposition, Congress belatedly appropriated fifteen thousand dollars to fund an exhibit “of the educational and industrial progress of the negro race in the United States.” Calloway was appointed special agent and turned to his friend and former classmate at Fisk University, W.E.B. Du Bois, for help.1

Du Bois was teaching sociology at Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University), and he agreed immediately. With $2,500 and the help of students and faculty, he went to work, taking over the exhibit planning and recruiting researchers across the South to gather data about Black American life.

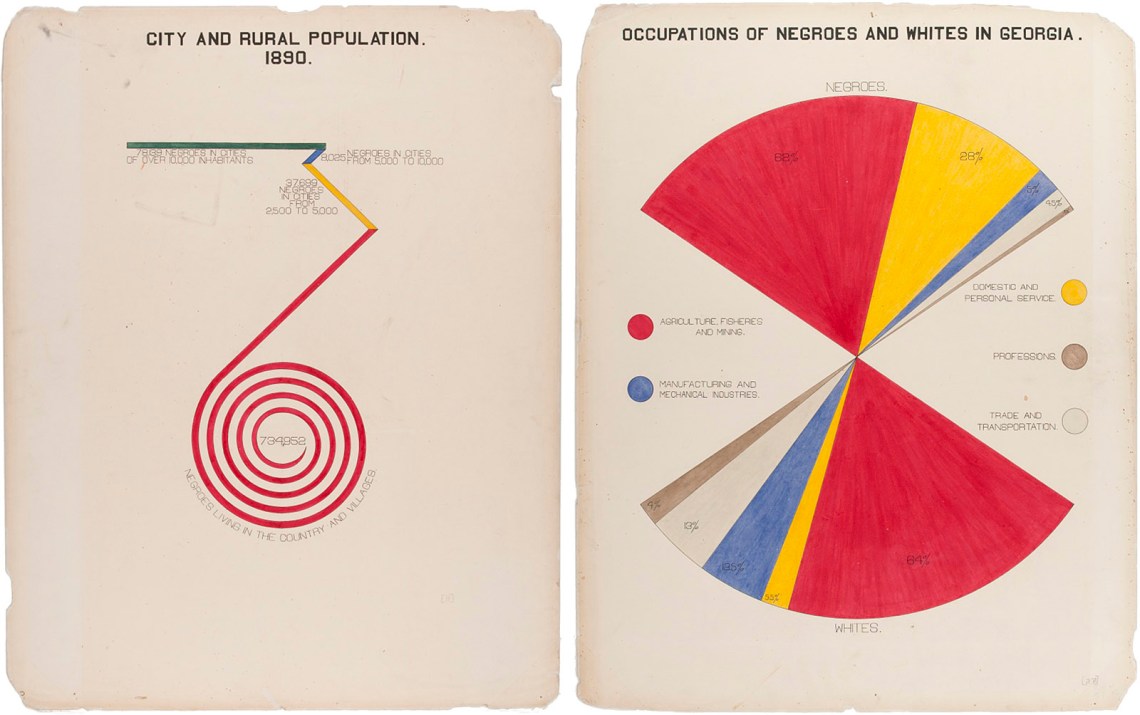

Two recent books return to this story with an emphasis on the exhibit itself—W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America and Black Lives 1900: W.E.B. Du Bois at the Paris Exposition. The former presents for the first time in book form the unusual infographics the Atlanta team created. The use of charts and graphs had become popular among economists, geographers, and others by the mid-nineteenth century, but they were not yet widely familiar to the general public. As Michael Friendly and Howard Wainer write in a brief but informative discussion of the Paris exhibit in their new book, A History of Data Visualization and Graphic Communication, Du Bois decided that research data colorfully presented would be the best way to present a “graphical narrative” showing the dramatic gains Black Americans had made since the end of slavery. His research was made possible, they note, “by the 1870 expansion of the US Census, which, for the first time, included the African-American citizens in the national accounting.”

Concentrating on census data and information from the state of Georgia, which had the nation’s largest Black population, Du Bois assembled graphs, pie charts, and maps displaying such metrics of prosperity as real estate ownership, marriage rates, literacy, and entrepreneurship. The exhibit included a record of 350 patents granted to African-Americans since 1834 and an infographic—“Negro landholders in various States of the United States”—that employed bar graphs demonstrating the ratio of owners to renters among Blacks in nine southern states.

Advertisement

Neither Black Lives 1900 nor W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits is intended to be a complete history of the Paris exhibit. For example, the tensions that arose between Du Bois, Murray, Washington, and Calloway over their differing visions of what the exhibit was supposed to convey are not explored. But then the story of Du Bois’s and Washington’s clashing philosophies has been told by many others. In these books, images take center stage.

W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits includes essays by coeditors Britt Rusert, a professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Whitney Battle-Baptiste, the director of that university’s W.E.B. Du Bois Center; the sociologist Aldon Morris; and the architectural designer and cultural historian Mabel O. Wilson. Silas Munro, an educator and designer, introduces and provides captions for the exhibit images reproduced in the book.

Black Lives 1900, edited by Julian Rothstein, includes a sample of the luminous photographs of African-American men, women, and children that were displayed alongside the charts and graphs. The images are arresting: a group portrait of African-American nuns in Sisters of the Holy Family, New Orleans, Louisiana, in full habit staring solemnly at the camera; dentistry students at Howard University examining patients; male and female students reading books and newspapers in the library at Fisk University. Had there been no Civil War, all of the people in those portraits, occupying positions of responsibility or preparing themselves to do so, in their fine clothing and looking healthy, confident, and prosperous, could have been treated as property.

An estimated 40 to 50 million people attended the Paris Exposition, which ran from April to November. It may be difficult for current generations, living in the era of the Internet and instant access to information, to imagine the impact of the world’s fairs of the time. They exposed people in the host country and travelers from all over to the societies displayed in the various exhibits, and often to startling new innovations as well. The Paris Exposition of 1889 had seen the debut of Gustave Eiffel’s tower, which in 1900 was still a subject of controversy—people could not decide whether it was a beauty or a blight. Among the marvels of the 1900 exposition was a moving sidewalk and an enormous Palace of Electricity—over 1,300 feet long and nearly two hundred feet wide—which provided power to the entire fair.

The separation of the “American Negro Exhibit” from the other US displays fit its purpose. Devoting an exhibit specifically to Black Americans suggested that they, indeed, constituted a separate society. In Du Bois’s words, the infographics made up “an honest, straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves.” The “Americanness” of the Blacks depicted was unquestionable. But given that Black people had started their journey outside the American polity and were still kept from full participation in it, seeing them as a nation within a nation made perfect sense. Morris writes:

The designation of a black nation conveyed the idea of a community with its own integrity, intricate culture, and complex social organization. This counterintuitive portrayal stunned throngs of world visitors who had never seen African Americans through this lens. The exhibit violated white thoughts about black people, especially Americans only three decades removed from slavery.

One feature that drew particular attention was the Library of Colored Authors. Daniel Murray and the team had collected more than two hundred books written by African-American men and women, along with pamphlets, periodicals, and newspapers.2 In an article that ran shortly after the fair opened, a New York Times correspondent commented, “It is perhaps not an exaggeration to say that no one would have believed that the colored race in this country was so prolific in the production of literature.”

This presentation of a group of Black Americans as successful and worthy of admiration fit squarely within Du Bois’s writings and philosophy at the time. He was in his “Talented Tenth” phase, thinking that only the most educated Blacks could shepherd the race into a better future. As he became enamored of socialism, he moved away from the idea that elites should be in the vanguard of Black progress and instead began to champion the power of the working class. At the turn of the century, however, he still believed it was important to showcase the existence of a middle and upper class among Blacks, people who could become part of a leadership cadre.

The chronicle of achievement Du Bois assembled began during enslavement. One of the charts, we learn from W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits, “was displayed in a wooden frame carved by a former slave who lived in Atlanta.” Battle-Baptiste and Rusert note that the choice to present the material in this way pointed “neither to historical progress nor to the overcoming of the slave past but to the ways that slavery continued to quite literally frame the present.”

While Du Bois certainly did not want people to forget the past, there is no question that he wanted to emphasize for viewers the hope of the present moment and the future. An infographic titled “The Georgia Negro: A Social Study” depicts a globe seemingly split in half and flattened: one circle contains Asia, Europe, Africa, and Australia; the other, North and South America. A line in script beneath the hand-drawn image announces that it is a map of the African diaspora (what is now often called the Black Atlantic). Lines drawn from Africa to places around the world show where Black populations existed, and different shadings show their relative concentration; a small star on the US map calls the viewer’s attention to Georgia.

The exhibit was designed to challenge European notions of superiority using some of the mechanisms that had been employed against Black people for centuries. “Maps,” as Mabel Wilson writes in W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits, were “critical tools in the European colonial project,” producing a

cartographic gaze that cultivated a way of seeing the world…. Cartography had given Europeans not only a way of navigating the oceans but also a means of exploring, mapping, and claiming territories in Africa, Asia, and the New World.

Du Bois claimed cartography, statistics, and science in general for African-Americans. The exhibit, with its presentation of information about Black prosperity and education—one graph showed that illiteracy rates among Black Americans were lower than those of Romanians, Serbians, and Russians—scored points without having to belabor them. Although the emphasis was on achievement, Du Bois did not want to paint too rosy a picture of Black Americans’ circumstances. He hand-copied Georgia’s various codes pertaining to slavery and Jim Crow to accompany the images of success, essentially saying, This is what we have been able to do in the face of legalized opposition to our advancement.

The “American Negro Exhibit” was important not only for the information conveyed; Du Bois believed that how it was presented mattered. While he had the world’s attention, he emphasized innovation: the colorful charts and bar graphs were a “form of infographic activism,” as Silas Munro writes in W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits, adding that the infographics’ strikingly “abstract shapes built from circles, triangles, and rectangles in bright primary colors” predated European avant-garde movements like Russian constructivism and De Stijl, and appeared at the Paris Exposition twenty years before the founding of the Bauhaus.

The reaction to the portraits of African-American life and the startling new way they were presented must have been all that Calloway, Du Bois, and their team could have hoped for. The exhibit won prizes from the exposition judges for its design and the history it presented, and Du Bois himself won a gold medal. The exhibit had a life after Paris in the United States, with stints in Buffalo, New York, and Charleston, South Carolina, and it received glowing attention in African-American newspapers.

This was all very Du Boisian. A New England boy who believed in propriety but reveled in competition, he had set a high task for himself and he had succeeded. It was a time when the notion of race uplift through the meeting of bourgeois ideals had great currency. As admirable and necessary as it was in 1900, however, it is likely that some readers today will pause over the exhibit’s underlying premise: that showing white Europeans and Americans examples of what we today call Black excellence would change their minds about Black people. This notion was in keeping with Du Bois’s scientific bent. It is also evidence of his basically hopeful nature, despite his presentation of himself as clear-eyed and realistic about relations between the races.

The truth is that whites on both continents had already had ample occasion to see and acknowledge the achievements of African-Americans. Frederick Douglass (represented by a statuette in the exhibit) was one of the most famous men of the previous century. Booker T. Washington, also born enslaved, was the head of the Tuskegee Institute and became the confidant of presidents; the title of his autobiography was Up from Slavery. It was certainly known that Black people had formed churches and civic organizations, and were in universities and professions, and it is hard to imagine that whites were blind to the fact that Black people had done all this while laboring under the burdens that members of the white community had placed upon them. Something other than rank ignorance fueled attitudes about Black people both during slavery and afterward.

In his Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson, who was frequently given to hyperbole, wrote with seeming sincerity that he had “never yet” found “that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration.” But he knew better. He assigned enslaved people to perform tasks at Monticello that required analysis and judgment: for example, he made George Granger the overseer of the plantation, and Granger’s son George Jr. the foreman of Monticello’s nail factory. It was simply not in Jefferson’s interest to admit publicly to other whites that the Black people he and his fellow Virginians were enslaving were capable individuals who might have thrived as free citizens, had they not been actively thwarted by the laws and customs of white society. Maintaining the racial hierarchy required living by and repeating agreed-upon fictions.

As much as the Europeans, and any white Americans who saw or read about the “American Negro Exhibit,” may have been impressed with what it showed them about Black Americans’ progress, there was no reason to think it would make most of them stop thinking that white people were better than Black people. More likely, the final judgment would be that some Blacks were better than whites had thought, or that there were more exceptions to the rule than they had realized. In truth, the issue was not then, as it is not now, a question that evidence can resolve. There would always be another test that Blacks had to meet, a standard that almost invariably found them wanting.

This is, perhaps, an overly cynical conclusion, made with the benefit of hindsight and from the safety of a position of relative privilege for which Du Bois and so many others laid the groundwork. The phenomenon of the “American Negro Exhibit,” as described in these books, reminds us that it is best to think of Black people’s journey through the American experiment as a series of stages, with each stage requiring a type of activism—a particular type of hope—best suited to the moment at hand. It is hard to imagine many Blacks today having any truck with the idea of gathering and offering proof to white people that Blacks are worthy and equal human beings, deserving of the right to live with dignity in their own country. And it is also unlikely that any Du Bois–like focus on propriety and rectitude as a means of advancement would escape criticism, though aspects of that criticism pose difficulties of their own.

Yet it may well be the case that what Du Bois and his collaborators achieved in Paris in 1900 was useful to African-American people at the time. Whether whites were moved or not—and the US press seems to have mostly ignored the exhibit—it was a source of great pride for Black Americans. The Black press made much of what had happened in Paris, spreading the news of the exhibit across the country. Perhaps it even strengthened the resolve to fight strenuously for civil rights. There was reason for optimism, as the small nation-within-a-nation was on the move, progressing to a future that seemed bright.

It is worth remembering, however, that Du Bois himself, who after Paris tried everything he could as hard as he could, eventually gave up on the United States, ending his days in Ghana. There was always more to solving America’s race problem than presenting evidence of Black talent.

This Issue

August 19, 2021

A Warning Ignored

The Burden of ‘Yes’

-

1

See A Small Nation of People: W.E.B. Du Bois and African American Portraits of Progress, Library of Congress, with essays by David Levering Lewis and Deborah Willis (Amistad, 2003). ↩

-

2

See Laura E. Helton, “Black Bibliographers and the Category of Negro Authorship,” in African American Literature in Transition, 1900–1910, edited by Shirley Moody-Turner (Cambridge University Press, 2021). ↩