1.

On August 11, 1965, Marquette Frye, a twenty-one-year-old African-American, was pulled over in Los Angeles while driving his mother’s Buick, then arrested after failing a sobriety test. In the argument that followed, Frye was struck by the officers as residents began hurling objects at them. Six days of civil unrest that became known as the Watts riots ensued, leaving thirty-four people dead and miles of the city pockmarked by charred ruins. When Frye died in 1986, his New York Times obituary called the riots “the biggest insurrection by blacks in the United States since the slave revolts.”

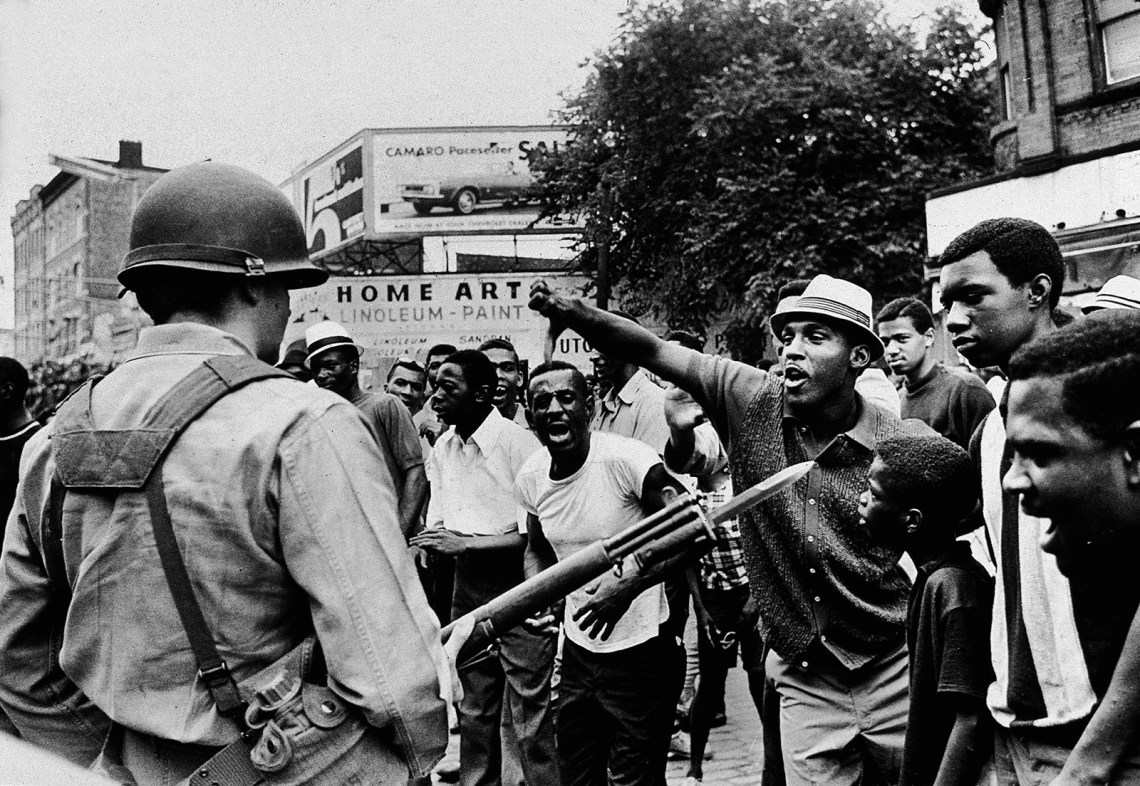

Between 1964 and 1967, black anger over policing practices, voter suppression, poverty, and economic inequality boiled over in cities throughout America. In the summer of 1967 President Lyndon B. Johnson created the Kerner Commission to examine the nearly two dozen uprisings that had occurred. (Formally called the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, it was referred to by the name of its chair, the second-term Democratic Illinois governor Otto Kerner Jr.) The eleven-member commission released its conclusions in March 1968, but it soon found that they were a forecast, not a review. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated the following month, and more than one hundred American cities exploded in just the type of violence that the commission had sought to understand, if not prevent.

The proximity of the two events—the report’s release and King’s death—allowed them to be conflated. It’s not uncommon for people to believe that the Kerner Commission examined the unrest of the entire 1960s rather than just its earlier episodes. But the timing is important. George Santayana’s dictum that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” is quoted with eye-rolling frequency, yet the Kerner Report shows that it is possible to be entirely cognizant of history and repeat it anyway.

Never was this more apparent than in the spring of 2020, when the half-century-old report reemerged as part of the stilted national dialogue on race, policing, and inequality. On the evening of May 25, four Minneapolis police officers arrested George Perry Floyd, a forty-six-year-old black man, for allegedly passing a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill at a convenience store. He ended up handcuffed on the pavement next to the patrol car while a white officer, Derek Chauvin, cavalierly knelt on his neck for at least eight minutes and forty-six seconds, despite the pleas of nearby people that Floyd needed medical attention, and despite Floyd’s repeated assertions that “I can’t breathe” and “They’ll kill me,” while crying out to his deceased mother for help. When Chauvin at last relented, Floyd was unconscious. He was taken by ambulance to a nearby hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

The reaction was immediate. The following day protesters began gathering on the block where he had been killed, which would soon turn into a shrine. In a Facebook post Jacob Frey, the mayor of Minneapolis, observed that “being black in America should not be a death sentence.” Minneapolis police chief Medaria Arradondo fired all four officers involved, which Frey described as “the right call.” The next day the mayor called for criminal charges against them. This bureaucratic reaction could not, however, stave off a tempest. By evening, hundreds of protesters with signs that read “Stop Killing Black People” had swarmed the streets of Minneapolis, gathering at the site of Floyd’s death and at the Third Precinct, where the officers suspected of killing him had worked. The sustained protests turned sporadically violent with looting and arson. On May 28 a multiracial crowd of demonstrators returned to the Third Precinct and, after police abandoned the building, burned it to the ground.

The video of Floyd’s death circulated around social media, sparking new outrage. By May 2020 there were enough videos of civilian deaths at the hands of police to nearly constitute a genre. A disproportionate number of them recorded the deaths of African-Americans. And there was growing concern on the part of activists and advocates that the public was becoming inured to the brutality being captured (largely on cell phones) with terrible redundancy. The video of Floyd’s death caused a different reaction in part because of its excruciating length. This was one reason the Floyd protests spread within days from an isolated spot on the south side of Minneapolis to Los Angeles, Atlanta, Washington, D.C., New York City, Salt Lake City, Chicago, Anchorage, and dozens of other American cities.

By the following week protests of some form had been reported in 350 US cities, and the National Guard had been deployed to maintain the peace in twenty-three states. “When the looting starts, the shooting starts,” President Donald Trump tweeted in response—the line was cribbed from Walter Headley, the notoriously racist Miami police chief who’d used it during hearings about crime in 1967. Some ten thousand Americans were arrested in the two weeks following Floyd’s death. Arson and looting caused more than a billion dollars in damage, and at least nineteen people were killed.

Advertisement

Floyd’s death was the product of, among other factors, police departments in the Minneapolis area with a troubled history of using deadly force, especially against people of color. In 2015 a Minneapolis police officer fatally shot Jamar Clark, an unarmed twenty-four-year-old African-American who eyewitnesses said was handcuffed, though police disputed that claim. No charges were brought against the officers involved, resulting in eighteen days of protests outside the city’s Fourth Precinct. In 2016 Philando Castile was pulled over in his car by police in Falcon Heights, a suburb of St. Paul. After Castile informed Officer Jeronimo Yanez that he was licensed to carry a firearm that was in the car, Yanez panicked and shot him five times in front of his girlfriend and her four-year-old daughter. Yanez was later acquitted of manslaughter charges. The following year Justine Damond, an unarmed woman, was shot and killed by a Minneapolis police officer named Mohamed Noor, which resulted in his firing and subsequent conviction on murder and manslaughter charges. Damond was the only white victim in the three incidents; Noor was the only black officer and the only one convicted.

In 2019 Bob Kroll, the president of the Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis, spoke at a rally for President Trump and thanked him for putting an end to the “handcuffing and oppression of the police” and “letting the cops do their jobs.” After Floyd’s death, Kroll remarked that the incident “does look and sound horrible,” conceding that Chauvin should have been fired, and yet his earlier comments suggested that rogue police felt emboldened by a president seemingly sympathetic to their way of operating.

Here is where the fifty-two-year-old insights of the Kerner Report remain most applicable today. “Police are not merely a ‘spark’ factor,” it tells us; they are part of the broader set of institutional relationships that enforce and recreate racial inequality. The problem is never simply the incident but the factors that made such an incident possible, even predictable. In 2019 Minneapolis ranked, according to US News & World Report, among the best places in the US to live, but it was also among the cities with the worst socioeconomic disparities between black and white residents, with a $47,000 gap separating the median household income of the two groups—shocking even for the United States. Seventy-six percent of whites in the area owned their homes; only a quarter of blacks did. This disparity is part of the long legacy of restrictive housing covenants—contracts prohibiting home sales to specific racial groups—which in Minneapolis began as early as 1910. In an op-ed following Floyd’s death, former Minneapolis mayor Betsy Hodges pointed to racial hypocrisy as a cause of the crisis:

White liberals, despite believing we are saying and doing the right things, have resisted the systemic changes our cities have needed for decades. We have mostly settled for illusions of change, like testing pilot programs and funding volunteer opportunities.

These efforts make us feel better about racism, but fundamentally change little for the communities of color whose disadvantages often come from the hoarding of advantage by mostly white neighborhoods.

Here again, the Kerner Report is instructive. “Our nation,” it warned in 1968, “is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” There were two realities in the Twin Cities, neatly calibrated by race.

After Floyd’s death the media, lawmakers, and the public wondered how the nation had come to this. The Kerner Report suggests that the more apt question should be why we have progressed so little beyond these combustible moments. The most recent incidents of state violence, the rioting in American streets, the often half-hearted scramble to understand the systemic failures and institutional rot that served as kindling for the latest conflagrations—all seem like a grim recurrence of a chronic national predicament.

2.

The Kerner Report has endured not simply for its prescience but also for the breadth of its analysis. The Kerner Commission was created by President Johnson’s Executive Order 11365 on July 28, 1967, as entire stretches of Detroit lay smoldering. Five days before the devastation began, police raided an after-hours bar and residents hurled rocks and bottles at them, which led to a nearly weeklong uprising marked by arson, looting, and forty-three deaths. Eleven days earlier, Newark had detonated following an assault on John Smith, a black cabdriver, by white police officers. Twenty-six people were killed and hundreds injured, while the city suffered an estimated $10 million in damages.

Newark and Detroit were just the most notable of the disruptions in more than two dozen American cities that summer. Johnson was not unfamiliar with the situation. In March 1965, in response to the campaign for voting rights orchestrated in Selma, Alabama, and the Bloody Sunday attacks on marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, he had declared his support for legislation protecting the right of African-Americans to vote. Johnson marshaled an almost unprecedented amount of political capital to see the bill through Congress—in full awareness that protecting black voting rights would fundamentally reorient American politics—and signed the Voting Rights Act into law on August 6, 1965. Five days later police in Watts pulled over Marquette Frye. The lessons after the disorder in Los Angeles were painfully obvious: it had taken the iron-willed might of the president and his huge Democratic majority in Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965, but these measures came too late for black residents, particularly those living in big cities.

Advertisement

The Kerner Commission can be viewed alongside the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts and the war on poverty as cornerstones of Johnson’s liberal views on race. The president, who grew up in Texas and saw firsthand the impact of the New Deal on the lives of disadvantaged whites, came to see that black Americans’ fortunes had been affected by the ways in which the welfare state had failed to include them. His willingness to both recognize and act on this realization made him a renegade among southern Democrats, whose resentment was further entrenched with the creation of the Kerner Commission.

Johnson charged the panel with answering three questions: “What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?” Addressing these questions, however, would mean answering dozens of subsidiary questions whose roots lay deeply tangled in American history and public policy. The commission members represented a cross section, albeit not a representative one, of domestic interests. Besides Kerner, it included two other Democratic elected officials: James Corman, a representative from California, and Senator Fred R. Harris of Oklahoma. They were joined by three Republicans: New York City mayor John V. Lindsay, Representative William M. McCulloch of Ohio, and Edward Brooke, a freshman from Massachusetts, who was the sole African-American in the US Senate at the time. The commission was overwhelmingly white (ten of the twelve members) and male (eleven of twelve). Katherine Peden, the commissioner of commerce of Kentucky, was the sole female member. Roy Wilkins, a political moderate who was the executive director of the NAACP, was the only other black member. In addition, I.W. Abel, the president of the United Steelworkers of America, represented labor, and Herbert Jenkins, the police chief of Atlanta, represented law enforcement. Charles Thornton, the CEO of Litton Industries, spoke for the manufacturing sector. Curiously, given the amount of detail the Kerner Report devotes to analysis of the ways journalists covered the uprisings, no representative of print or broadcast media was involved with the commission.

Johnson was hardly the first politician to press for answers to the questions he posed to the commission. In 1919 the Chicago race riot—one of dozens that took place during the so-called Red Summer that year—inspired a commission that sought to trace its origins and causes. In 1935 a riot broke out in Harlem following an allegation that police had killed a Puerto Rican teenager, and in its aftermath a commission found the catalysts deeply rooted in segregation and inequality. Similar incidents took place in Detroit and Harlem in 1943. Even as the Kerner team began its work, an analysis of the Newark riots that came to be known as the Lilley Report was underway. Most of these reports struck similar themes. What differentiated the Kerner Commission was the historical scope of its investigations: it was seeking to understand not a singular incident of disorder but the phenomenon of rioting itself. The concluding report spoke with a strikingly unified voice about the problems that the various participants sought to understand. And that voice was an unabashedly integrationist one.

Its most salient observation was that even though the police had been involved in these volatile incidents, American cities were not simply facing a crisis of policing. Rather, police were the tip of much broader systemic and institutional failures. The Kerner Report, like the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, published twenty-four years earlier, noted that the “problem” had been, first and foremost, inaccurately diagnosed. The “Negro problem” was, in fact, a white problem, or as the report noted in one of the oft-quoted sections of the summary:

What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.

The formulation was significant, if not novel—W.E.B. Du Bois, who had died just five years before the report, E. Franklin Frazier, Abram Harris, Horace Cayton, and St. Clair Drake, among many other black social scientists, had been making this point since the turn of the twentieth century. Yet the people cosigning this assessment—whites, by and large—had the ear of the most powerful policymakers in the nation. Myrdal’s indictment in An American Dilemma helped define the liberalism of the postwar United States; it’s impossible to read the Kerner Report, particularly its expansive set of proposals, and not suspect that a similar ambition was at play. The condition of the Negro was the truest barometer of American democracy. In a best-case scenario, the Kerner Report would have become a kind of guidebook for the war-on-poverty policies then being enacted by the Johnson administration.

The commission recommended new community-based guidelines covering how police should interact with citizens of “the ghetto,” as it dubiously classified black communities. It devoted an entire chapter to how justice should be administered during and after riots; it suggested a national network of neighborhood task forces and local institutions that could bypass the bureaucracy of city administrations and head off problems before they erupted. It offered specific proposals for housing, welfare, education, and employment, including an expansion of municipal employment and the establishment of “multi-service centers” to connect residents of these communities with job placement and other forms of assistance. The commission’s members perceptively suggested that the white news media that reported on these uprisings were also a symptom of the bigger problem. Social upheaval that had been created and then maintained by overwhelmingly white institutions was reported upon by other overwhelmingly white institutions. This constituted, in the commission’s assessment, a racial conflict of interest.

Notably, the report reiterated the idea that men were the presumptive heads of their households, and the growing numbers of female-led families were relayed in ominous tones. Although the report’s analysis of the plight of black families was shot through with patriarchal presumptions—it carried a strong whiff of the condescension of Daniel P. Moynihan’s much-derided 1965 study, “The Black Family: A Case for National Action”—the validity of its recommendations has in great part endured. This is why the 1968 report requires a close reading in the twenty-first century. The Kerner Report came out at the zenith of liberalism’s influence in the twentieth century. The warnings issued in it were meant to alert the public to what would happen if the nation did not adopt a deeper, more committed, and truer form of liberalism that enfranchised black people.

In this way, it became nothing less than a time capsule of the era. And yet, for all its strengths, it failed to discern that much of the American public had not the slightest appetite for such a form of liberalism. The growing ranks of the “silent majority” wanted just the opposite, as the upcoming presidential election showed. In eight short but crucial months, the American political scene changed completely.

3.

The year 1968 was marked by anarchic rage and protest, much of it against the Vietnam War, which produced one reaction within the liberal establishment and another among conservatives. The violent disruptions at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago handed the Republican presidential nominee, former vice-president Richard Nixon, a political windfall. How could Democrats run the country, his campaign suggested, if they could not even run their own convention? Moreover, the reorientation of American politics that Johnson predicted as he signed the Voting Rights Act had begun. Nixon had been beaten by Kennedy in South Carolina in 1960 but defeated the Democratic nominee, Hubert Humphrey, there eight years later. For decades the liberal wing of the Democratic Party had struggled to find equilibrium with its racially and socially conservative southern wing. The increasing southernization of the GOP meant that the voices of backlash had found a new avenue for expression.

Accelerating changes in the American economy—the first winds of deindustrialization, in particular—meant that it would be difficult to bring black workers up to parity with their white counterparts. Whites, too, would increasingly struggle to keep up with their own economic expectations, which further exacerbated their racial resentment. Implicit within the “law and order” appeals of the Nixon campaign was a rebuke to the uprisings of the era and to the Democratic leaders who had presided over the cities where they occurred. (This criticism had so much potency that it would continue to be lobbed at Democratic politicians for decades, most notably in the spring of 2020, when the Trump administration assailed the mostly Democratic mayors of cities where rioting took place.) While the Kerner Report maintained that the riots were a result of the absence of true liberalism, the emerging consensus held that they were the product of too much of it. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the new administration.

George Romney, the former governor of Michigan, served as Nixon’s first secretary of housing and urban development. His department was equipped with a powerful new tool: the 1968 Fair Housing Act, the third piece of landmark civil rights legislation of the era, passed by Congress after King’s assassination. Romney, who as governor had coordinated the response to the 1967 Detroit riots, remarked, “Force alone will not eliminate riots. We must eliminate the problems from which they stem.”1 But his vigorous enforcement of the FHA during his tenure at HUD created a backlash among Republicans and isolated him from Nixon. His departure from the department in 1972 marked another turn in the GOP’s politics away from the concerns of antidiscrimination.

The Kerner Commission had called the criminal justice system unjust, indicting racism for creating many of the troubles within black America. In the decade to come, this line of thinking was more likely to be attacked for leniency; it was supplanted by the view that racism had diminished and that black poverty was the product of bad choices, weak values, and lack of motivation. White society, exonerating itself from any culpability in the creation of a brutally segregated black America, now felt comfortable enough to offer judgment from afar. Aside from the one-term interlude of Jimmy Carter’s presidency, this conservative position dominated the presidency for nearly a quarter-century after Johnson left office. When liberalism reemerged in the early 1990s, it came in the form of a pro–death penalty, corporate-friendly southern governor who pledged to put one hundred thousand new police officers on America’s streets, which is to say it was hardly recognizable as liberalism at all.

It was a strange and bitter irony that Bill Clinton’s political ascent was in some ways facilitated by yet another riot: the colossal uprising that leveled swaths of Los Angeles in the aftermath of the trial of four white police officers for brutally beating Rodney King in March 1991. Unlike similar incidents in the 1960s, such as the Frye altercation that set off the Watts riot, this flagrant abuse was captured on video, yet even that proved insufficient for a jury in Simi Valley, California, to convict the officers of a single charge brought against them. On April 29, 1992, the day the verdict came down, Los Angeles exploded. The destruction, estimated at roughly $750 million, ushered in yet another commission—this one chaired by the diplomat and Johnson’s former attorney general Warren Christopher—yet another report, and yet more suggestions that would prove to be politically inert. Unlike the Kerner Report, the Christopher Report remained narrowly tailored to the specific question of policing in Los Angeles, examining none of the broader social dynamics for which bad policing was representative. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor noted in The New Yorker:

The period after the LA rebellion didn’t usher in new initiatives to improve the quality of the lives of people who had revolted. To the contrary, the Bush White House spokesman Marlin Fitzwater blamed the uprising on the social-welfare programs of previous administrations, saying, “We believe that many of the root problems that have resulted in inner-city difficulties were started in the sixties and seventies and [those programs] have failed.”

The administration presented this argument with a straight face despite black unemployment being roughly double white unemployment in the year leading to the uprising. President George H.W. Bush appeared patrician and out of touch. The younger, more affable Clinton appeared empathetic and attuned, which helped him cement support among African-American voters that fall.

The appearance of empathy was just that. Two years into his first term Clinton signed the 1994 crime bill, a punitive piece of legislation that was to widen racial inequities. He pushed for and signed measures meant to wean recipients off welfare, a capitulation to the canard that the system was rife with fraud and underwrote indolence. Blacks, in the white parlance of the era, were getting too much “free stuff” from the government. In his 1996 State of the Union speech Clinton informed the nation that “the era of big government is over.” The renunciation was complete.

This state of affairs did not begin to change significantly until the stunning election of Barack Obama in 2008, and not entirely because of forces within his control. Wary of committing unforced errors on the subject, the first black president was generally reluctant to address race. Circumstance forced his hand. On August 9, 2014, eighteen-year-old Michael Brown was shot and killed by police officer Darren Wilson on a side street in Ferguson, Missouri, a working-class suburb of St. Louis. Months of sustained protests pushed the administration to form a task force on twenty-first-century policing. The Department of Justice conducted an investigation of the Ferguson Police Department and filed a report that could well have been an appendix to the Kerner Report. The recognition that policing was just one part of a broader systemic failure began to creep back into public recognition. And yet, scarcely six years later, the nation once again witnessed outrage in the streets.

The Kerner Report was a tocsin that Americans chose to ignore.2 In many ways American society did exactly what it warned against and, as the disturbances of recent years suggest, reaped the consequences it predicted. Its warnings remain strikingly relevant.

This Issue

August 19, 2021

The Burden of ‘Yes’

The Color Line

-

1

Romney’s quote about Detroit was resurrected in June 2020, when his son, Utah senator Mitt Romney, tweeted the comment in reference to the unrest that attended the murder of George Floyd. The comment was also implicitly a rebuke of President Trump, who had, not coincidentally, borrowed Nixon’s language of “law and order” for both his 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns. ↩

-

2

The report proved to be the high-water mark of Otto Kerner’s career. Upon completing his service on the commission, Kerner stepped down as governor of Illinois to accept an appointment as a federal judge by Johnson. Five years later he was convicted on multiple counts of mail fraud, perjury, and conspiracy (all except four charges of mail fraud were later overturned) and, faced with almost certain impeachment, resigned from the bench. Sentenced to three years in federal prison, he began serving his term but was diagnosed with terminal cancer and released early. He died in 1976. ↩