When Francis Galton, Charles Darwin’s problematic cousin, wrote of taking stock of his own “mental furniture,” he meant assessing the background experiences and assumptions that informed his thought—the objects we barely see but instinctively accommodate as we move around the metaphorical room. Galton’s scientific star has dimmed since his death in 1911 (fathering eugenics has consequences), but he wasn’t wrong about furniture.

Last summer, when a flamboyantly stately French commode popped up in an episode of the Frick Collection’s lockdown lifeline, Cocktails with a Curator, I was surprised to find that I could summon only the vague memory of something bulky at the foot of the Frick staircase. I can recall in detail the blue-and-gold upholstery, brass tacks, and lumpy finials of the chairs in the Vermeer paintings that flanked it, but the commode itself dissolved into the building’s baseline domestic pomp. This mind’s-eye astigmatism was not (or not just) the result of a personal preference for the Dutch Republic over the Ancien Régime; it is symptomatic of a hierarchy in the modern economy of attention: the chairs belong to a painting; the commode is just a chest of drawers.

Anyone who has met the art world knows that painting rules the roost, but if it seems self-evident that Vermeers operate on a higher aesthetic, emotional, and conceptual plane than a dresser, it is worth noting that in the 1780s, when Jean-Henri Riesener created this one (for Marie Antoinette, no less), his work was highly treasured and vastly expensive, while Vermeer paintings were trading for modest prices under other artists’ names, his own having disappeared from histories of Dutch art. To state the obvious: beyond survival needs, there is nothing natural or inevitable about the values we put on the things we make or on the work done to make them.

The treasures of the Frick Collection have now been installed with fresh simplicity and greater spaciousness at Frick Madison.1 The temporary change of venue is illuminating in many ways but has been particularly transformative for the furniture, vases, and other “decorative arts” (a term that mixes admiration and dismissal in a breath). Taking a star turn in one of Marcel Breuer’s sleekly muscular galleries, the commode stands on a dais against a wall painted the color of fog; a trio of green-and-gold Sèvres porcelains float on discreet supports above. This is the taut, uncluttered display language of contemporary art (the arrangement, allusive and elusive in equal measure, bears a more than passing resemblance to a Barbara Bloom installation), and it constitutes a tacit challenge to consider the objects presented as art. Or at the very least, to ponder why it might be hard to do so.

Visual art may sit at the top of the prestige pyramid, but it occupies a tiny corner of human productivity and consumption. One of the gifts of Glenn Adamson’s profound and engaging new book, Craft: An American History, is its lack of interest in considering art as a special class of production at all. He doesn’t so much ignore the pyramid as flatten it: “Whenever a skilled person makes something using their hands, that’s craft.” Adamson’s book is timely, not just because it had the luck to be published during a global crisis that demanded manual mask-making and the desperate invention of table-top activities for under-twelves, but more importantly because of issues it brings to the fore about labor and value.

The photographer, filmmaker, and writer Allan Sekula, who died in 2013, spent his career picturing the undervalued labor that goes on, often unseen, in places like Canadian coal mines and Panamanian-flagged container ships, and trying to identify the mechanisms that put those values in place. The essays collected in Art Isn’t Fair were published over the course of about forty years and interlace histories of photography, industrialization, political oppression, and economics in elliptical and often moving ways as Sekula strove to understand them “from below, from a position of solidarity with those displaced, deformed, silenced, or made invisible by the machineries of profit and progress.” Adamson and Sekula take different approaches and rely on different areas of expertise, but the central story they tell is the same: how expressions of mind have gained hegemony over manipulations of matter, and what has been damaged in the process.

For much of European history, picture-making and furniture-making enjoyed similar status: areas of skilled manufacture conducted by individual artisans or small workshops organized into trade-specific guilds. The competencies required to join those guilds were passed on through apprenticeships. People learned by doing. During the sea change of the Renaissance, however, painters and sculptors began to see themselves as more akin to poets and philosophers than to goldsmiths and carpenters. There was, they felt, a substantive difference between containers for ideas and cupboards for linens. In 1648, at the urging of the painter Charles Le Brun, Louis XIV established the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, drawing an official line between “artist” and “artisan.”

Advertisement

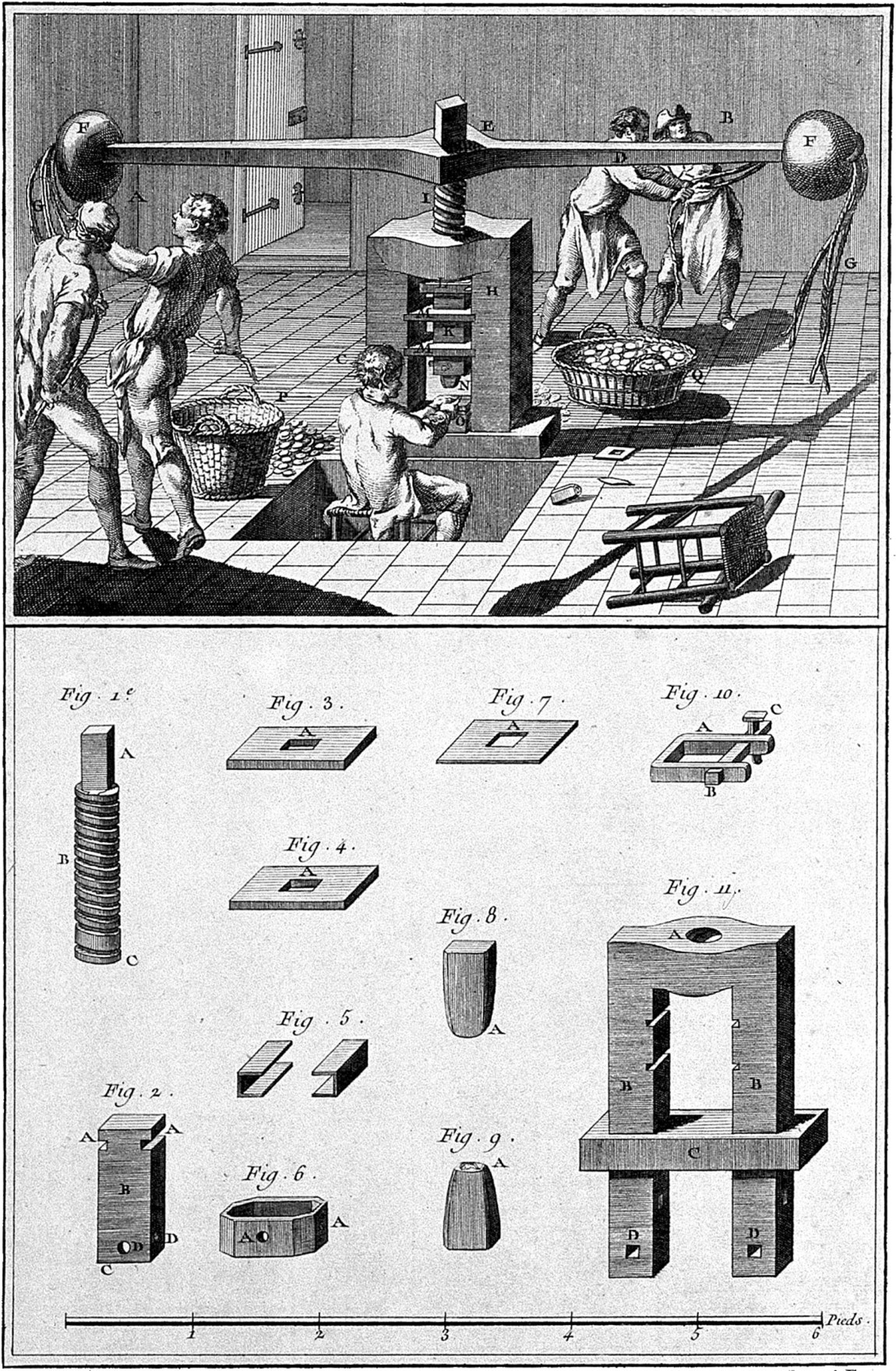

A century later, when Diderot and d’Alembert assembled their user’s manual for the Enlightenment, the great Encyclopedia, they placed painting and poetry under the heading “Imagination” and philosophy under “Reason,” while carpentry and marquetry joined locksmithing and pin-making as “trades.” A few years on, in The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith borrowed their account of pin-making to illustrate the efficiencies of divided labor, codifying the theory behind a practice already in motion: coherent artisanal understanding (the manual and engineering skills required to construct a commode, for example)2 was dismembered into simple repetitive tasks performed simultaneously by different people, so more things could be made in less time.

Sekula calls attention to the structure of illustrations of trades in the Encyclopedia, whose standard form places a scene of workshop activity at top and larger diagrammatic representations below with inventories of tools, cutaway views of structures, or close-ups of working hands. In their didactic clarity, their promise that everything could be learned from books, Sekula saw an incipient transfer of power: “Technical knowledge would flow from artisans to intellectuals,” who would repackage it as methods to be imposed on workers. Humanity was divided “into two camps, those who work and those who know.” Looking at America, Adamson sees the same phenomenon: a “declared preference, among the cultural elite, for knowing that over knowing how.”

Two hundred and fifty years later, this dynamic still holds, though most of those skilled trades have been subsumed into industrial processes and largely unskilled jobs. Some survive as craft hobbies; a few have been elevated to quasi-academic status in university art departments, though suspicions about the intellectual content of pots remain.

The current exhibition at the Whitney Museum, “Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019,” offers an account of how this has unfolded in contemporary art. In a museum setting, “craft” is generally understood in opposition to “fine art” media, encompassing textiles (though not stretched canvas), glazed pottery (though not terra-cotta figures), quilting (though not collage), things made with embroidery needles (though not etching needles). The schema of gender, racial, and social privilege underlying these distinctions is not exactly subtle.

In the 1950s the studio craft movement, originating in the United States, tried to make a case for fiber and clay as legitimate vehicles of modernist abstraction, but even stars like Lenore Tawney and Peter Voulkos were seen as weavers and potters first and artists only secondarily. Commenting on the Museum of Modern Art’s 1968 “Wall Hangings” exhibition, the sculptor Louise Bourgeois argued that while real art challenged the viewer, “these weavings, delightful as they are, seem more engaging, and less demanding.” Fair enough, perhaps, but “engaging wall hangings” could well describe much Color Field painting, and it’s hard to see how Tawney’s geometries are any “less demanding” than those of Gene Davis or Dan Flavin.

In the end, craft—like photography—was freed from its medium-specific purgatory by conceptualism. The shift is visible at the Whitney in works from the late 1960s and early 1970s by Robert Morris, Eva Hesse, and Alan Shields. All play with the catenary droop of soft materials, allowing the artwork, in Hesse’s words, to “determine more of the way it completes itself.” These artists were defying the habitual hardness and fixity of “serious art,” but also evading any suggestion of craft virtuosity: their materials were store-bought and their processes experimental. Similarly, when Miriam Schapiro and Faith Ringgold took up needle and thread, it was understood as a strategic choice, rich with underdog cultural associations, rather than the product of specific manual training.

In a neat adaptation of the Encyclopedia’s transposition of doing into thinking, amateurism with regard to artisanship became a mark of professionalism with regard to art. This does not preclude making things beautifully: the Whitney show is full of finely fashioned things, such as Shan Goshorn’s woven inkjet baskets, the embroideries of Jordan Nassar and Elaine Reichek, and Charles LeDray’s captivating vitrine filled with thousands of Lilliputian porcelain vases, pitchers, and cups, each visibly handcrafted. These are objects that attest to the pleasures of their own making, but they are in the museum because of how they can be seen to articulate ideas.

Photography, like craft, complicated the art/artisan divide. To begin with, there was the confusion over whether a photograph was just a thoughtless trace of the world, like a stain, or whether, as a picture, it had some claim to deductive reason. Then there was the problem of profusion. Even in an era of hulking box cameras and arduous exposure times, it was quicker and easier to take a picture than to paint one. The result was an unprecedented flood of images produced by and for all classes of people. Each of those images, furthermore, contained an unmanageable glut of information. Painters and engravers could—indeed had to—control what got put in and what got left out of a portrait (eyes were important, a shaving scab less so). Part of visual art’s claim to intellectual stature lay in that decision-making, the editing and emphases that turned a picture into a poem, or, in the case of the Encyclopedia, a lesson plan. The daguerreotype, on the other hand, naively reproduced every pore that met its lens.

Advertisement

“The anarchy of the camera’s prolific production,” Sekula wrote, “had to be tamed by the filing cabinet,” by which he meant the photographic archive. He contrasts the late-nineteenth-century photographic activities of the Parisian police official Alphonse Bertillon, inventor of the mug shot, with Francis Galton, who promoted the “composite photograph,” a typological portrait made by superimposing multiple faces from some category of persons, such as criminals. For Bertillon, aiming to identify individual miscreants, the photograph’s specificity enhanced his existing system of biometric measurements. For Galton, who wanted to identify shared characteristics, photographs were data to be aggregated in a kind of visual statistics.

Of the two, the mug shot proved to be the more useful, but Sekula draws an unexpected line from Galton to Alfred Stieglitz, the champion of photography as a modernist art form: “Both Galton and Stieglitz wanted something more than a mere trace, something that would match or surpass the abstract capabilities of the imaginative or generalizing intellect.” Art and science united in their essential desire to discover invisible truths—emotional or evolutionary—through treatments of the visible instance. Sekula was both fascinated and troubled by photography’s ability to flicker between the job of recording the world and that of purveying aesthetic experience. At least with a painting you know you’re looking at a lie.

Perhaps this explains the Napoleonic Code of criticism Sekula used in passing judgment on artifacts in the dock—nothing in “the archive of human achievements can be assumed to be innocent,” he wrote in 1983. If some of his verdicts seem harsh (the intercultural empathy promoted by Edward Steichen’s “Family of Man” exhibition and catalog is, amid its virtues, also “a prototype for the new post–Cold War ‘human rights’ rationale for military intervention”), others were prescient. His five-part disquisition, “Between the Net and the Deep Blue Sea” (2002), chases reflections between the social traffic in photographs (digital and otherwise) and the maritime traffic in commodities—two systems that shape our lives in ways that, at the time of his writing, were rarely examined. Documentary photography has the power to put stumbling blocks in the way of such smooth abstractions as “global trade” by picturing real individuals and places and suggesting lives lived and lost, but in other hands photography is the insidious ally of the powers that be: “We also need to grasp the way in which photography constructs an imaginary world and passes it off as reality.”

Where Sekula saw an asymmetric war of representations waged against the working classes by the bourgeoisie (the manipulators of fiscal, intellectual, and artistic abstractions), Adamson finds a much messier, multilateral struggle among individuals trying to shake the circumstances in which they find themselves. Acknowledging the legal, social, and economic constraints that dictate those circumstances, he is interested in craft as a form of personal agency. Craft: An American History is filled with pocket biographies of people who fail to take what from a distance might seem to be clear sides: the dress designer Elizabeth Keckley, for example, whose 1868 autobiography was subtitled “formerly a slave, but more recently modiste, and friend to Mrs. Abraham Lincoln,” and whose client list also included the wives of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee; the textile and interior designer Candace Wheeler, who set up needlework cooperatives for women in need (including George Custer’s widow), and also partnered with Louis Comfort Tiffany on the Alhambra-meets-Valhalla splendor of the Park Avenue Armory’s Veterans Room. There is the custom car builder George Barris, whose body shop Tom Wolfe compared to an art gallery, and the mid-twentieth-century art-potter who warned of the “quite possible degeneration in American culture” portended by hobbyists and craft kits. There are social agitators (Mother Jones was a seamstress), patricians in search of self-actualization, and hippie housebuilders with “a high tolerance for ad hoc solutions.”

To start with, however, he turns to an American icon: John Singleton Copley’s portrait of Paul Revere, teapot in hand, engraving tools positioned in the foreground like the regalia of a monarch or the attributes of a saint. This young Revere had not yet pirated the engraving (as it happens, by Copley’s half-brother, Henry Pelham) for his broadside decrying the so-called Boston massacre, or sprung to his saddle to spread the alarm through every Middlesex village and farm. But Revere’s twin persona as artisan and patriot would come to stand for a particularly American ideal, redolent of honest labor (as opposed to financial speculation or aristocratic inheritance) and stalwart independence. Adamson, however, is equally interested in Revere’s subsequent career, when he expanded his metalworking operations into cast-iron sash weights, bronze bolts, and copper sheathing. In place of bespoke production, Revere standardized and systematized; in place of apprentices, he hired wage labor. Portraits from the early 1800s show a frock-coated gentleman, no burin in sight. He had moved himself from the hands-on scene at the top of the Encyclopedia engraving to the analytic expertise at the bottom. It was an ability that would increasingly separate winners from losers in a putatively meritocratic system.

Adamson offers the example of the late-eighteenth-century shoe trade, in which entrepreneurs reorganized what had been an entirely custom business (a single cordwainer might measure the feet, cut the leather, and assemble the shoes), introducing standardized sizes that made it possible to outsource divided labor (leather cutting, for example) to journeymen unattached to any permanent employer—a preindustrial gig economy. The upside was that shoes became much more affordable. The downside was “a new thing among white Americans: a skilled underclass.”

The qualifier “white” is important. If New England attitudes toward work came to seem prototypically American, they existed alongside quite different alternatives, most obviously those of the enslaved and their enslavers, but also those of Native peoples. Adamson tells of early English dismay at the making of wampum: though they had seen wampum belts of particular patterns being used to mark treaties and encode narratives, the English wanted wampum as currency and found Wampanoag methods of shaping and boring the shells too slow for the beads’ market value. Having reduced wampum’s value to a single metric, they saw Wampanoag efforts as wasted energy and symptomatic of minds incapable of rational thought. Native people might have a “Genius for Mechanics,” in the words of an eighteenth-century French cleric, but were “not fit for the Sciences,” meaning advancement to the life of the mind. It was a judgment that would long endure, levied against women, Blacks, rural whites, and whatever immigrant group was freshest off the boat.

We may now be better attuned to the biased application of that judgment, but the formula underlying it remains so engrained, it has been difficult to recognize it as a choice rather than a truth. To wit: that the point of labor is production, the point of production is consumption, and any solution that maximizes the consumption-to-labor ratio is a net good.

Automation is one natural outcome of this belief, but both Adamson and Sekula note that man and machine have always been in this together. “The first cotton gin was a handmade object, executed with skill and ingenuity,” Adamson observes. And even in the industrialized era, the space between hand and machine can be vanishingly slim, a fact purposely elided, Sekula argues, in industrial photographs that consistently celebrate glossy machinery absent the workers needed to run it. Of the Romantic taste for pictures of crashing waves and fiery furnaces, he observes drily:

The sublime that we’ve inherited from the eighteenth century is inadequate to explain the experience of people whose lives are expended in the material domination of nature. The category of the awed spectator does not apply to those who live with the violence of machines and recalcitrant matter.

With regard to our own time, Adamson quotes the labor historian Louis Hyman: “To understand the electronics industry is simple: every time someone says ‘robot,’ simply picture a woman of color.”

Adamson debunks the fantasy of preindustrial America as a leather-aproned Eden where log cabins and spinning wheels somehow aligned with libertarian leisure. Craftsmen spent long days on boring, repetitive tasks with little reward; log cabins were not one-man monuments to rugged independence but required crews of trained builders to construct. He calls out the myth of the self-made man as “propaganda aimed from the top of the social ladder at the bottom.”

He takes seriously the economic entrapment of industrial workers, as well as the rising sense that some important component of lived experience had gone missing, and not only for the poor. Resistance may have been futile, but it was constant, shimmying across political and ideological lines with a promiscuity that makes a mockery of our supposedly intractable red/blue divides. Utopian religious sects like the Shakers, the Oneida Community, and the Amana Colonies combined handcraft, communitarian economics, and piety. Transcendentalist and pragmatist philosophers tried to broker an agreement between palpable experience and the life of the mind. Bourgeois reformers set about bettering the poor through craft, with varying degrees of compassion and condescension.

In Chicago, Jane Addams’s Hull-House was a model of respectful diversity and set the standard for settlement houses across the nation, while the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, which also inspired many imitators, kidnapped students in order to “kill the Indian in him, save the man.” Hampton University and the Tuskegee Institute both originated as institutions for training freed slaves and their children in manual arts and schoolteaching, a curriculum less threatening to whites than one in law or political economy, and also less applicable to a rapidly industrializing nation. (These schools and others soon expanded to include the full completement of academic subjects.)

Rural inhabitants of the Southern Highlands of Appalachia, of tribal areas of the Southwest, and of the Low Country of the Southeast were celebrated for the presumed antiquity of their craft traditions, though many of those “traditions” were invented or modified to please distant marketplaces in what Adamson terms “enactments of…authenticity.” (William Goodell Frost, the founder of Fireside Industries at Berea College in Kentucky in the 1890s, went so far as to publish the institution’s magazine in a fictitious mountain dialect.) At the turn of the century, organized labor—then “the largest and most powerful craft organization in the country”—urged workers of the world to unite; in 1971 the free-spirit vade mecum of tools and notions, The Whole Earth Catalog, ran the slogan, “Workers of the world, disperse.”

Through it all, art continued to be the valorized exception to the rule. In art, the inefficiencies of hand facture were understood as essential markers of meaning. This was the crack through which William Morris and the British Arts and Crafts movement hoped to sneak an army of empowered craftsmen. Stitching medievalist aesthetics to socialism, Morris argued in words and wallpaper that “joy in labor” would be the antidote to the psychological distress, social inequality, and ugliness of the industrial world.

American amateurs and artisans were inspired. Gustav Stickley spread the message through his magazine, The Craftsman, and “furniture possessed of deep gravitas,” as Adamson puts it. The Stickley sideboard at the Metropolitan Museum may be similar in function to the Riesener commode, but is its antithesis in every design particular: in place of virtuosic curves, Stickley asserts rectilinear volumes; in place of intricate marquetry, he showcases plain lumber; in place of seamless joinery, he makes tenons overshoot their mortises. The result is starkly handsome and almost theatrically artisanal, the quartersawn-oak equivalent of the exposed ductwork and framing in Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano’s Pompidou Center. Using form to articulate philosophical positions, Stickley’s furniture behaved much like art, with the added advantage that it could store your forks.

The promised revolution never came. In a compromise that should feel very familiar, consumers bought into the idea that they could improve the world through their decorating choices, while American Arts and Crafts leaders rarely “paid more than lip service to the project of empowering the skilled worker,” according to Adamson. In The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Thorstein Veblen tagged it all as a subspecies of conspicuous consumption. In an industrial society, visible marks of hand facture perform the same social function as the commode’s show of extraordinary virtuosity in a preindustrial time: they establish social standing.

Alas, the battle to define the purpose of work was won not by Morris’s utopian novel of 1890, News from Nowhere, but by Frederick Winslow Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management, from 1911. Taylor, the socially challenged evangelist of efficiency, wrote of “gathering together all of the traditional knowledge which in the past has been possessed by the workmen and then of classifying, tabulating, and reducing this knowledge to rules, laws, and formulae” that would “replace the judgment of the individual workman.” It was, Sekula writes, “open war on the very category of the artisan,” and it is hard to argue with Adamson’s characterization of Taylor as “a cartoon villain…a man who devoted his life to the merciless control of bodies and minds: joylessness in labor.”

Though Taylor’s principles were rarely put into practice with the vigilance he advised (workers tended to walk out), they flourished as a set of structures and expectations for white and blue collars, eventually becoming internalized as metrics of self-worth, where they continue to feed an industry of agitated self-help books (Increase Productivity Right Now!, Shut Up and Focus, Stop Procrastinating Now!), life-hack websites, and toy traffic lights promising to instill time-management skills in toddlers.

One of the lessons of Adamson’s book is that craft never really goes away, but by the mid-twentieth century its satisfactions—the sense of hand and mind working on problems together—had largely moved out of the workplace and into the garage, the scouts’ tent, the kitchen, the geodesic dome. The dream of another way of living persisted at the fringes, along with the hope that, as the craft advocate and reformer Allen H. Eaton wrote in 1937, “the time will come when every kind of work will be judged by two measurements: one by the product itself, as is now done, the other by the effect of the work on the producer.” Those dreams have been thwarted by business interests, but also by human nature (people like things, and economies of scale generally make things cheaper, no matter how many microbreweries and artisanal cupcake shops may blossom on recently gentrified streets), and by mental furniture.

That may be changing. Certainly the impulse to take stock of our cultural furniture has gathered strength as the world awakens from its Covid nap to find its glaciers still melting, its attics still overstuffed, and its people still overworked and underemployed. Also, we may not have a choice. There is an endgame here not addressed by Sekula or Adamson: a future, now in the near view, in which intellectual work is taken over by machines. The very thing that formed the presumptive basis of our social hierarchy—a talent for deducing principles from data—is what computers are good at. Not just good—better than we are. (Parents, don’t let your babies grow up to be accountants or radiologists.) Meanwhile, aspects of artisanship that escaped effective mechanization—tactility, improvisation, and the many small attributes we recognize as “human touch”—are still difficult for machines. The advice from AI researchers is that if you want to guarantee yourself a job, train as a hairdresser.

The resulting reconfiguration of wealth and power could well play out in horrible ways, but we cannot rule out the nondystopian possibility in which larger groups of people find themselves at liberty to ask not just “How shall we spend our money?” but “What should we do with our time?” There may come a time in which the logic of efficient production simply ceases to be logical.

This Issue

August 19, 2021

A Warning Ignored

The Burden of ‘Yes’

The Color Line

-

1

See Colin B. Bailey, “Masterpieces Unmediated,” The New York Review, May 13, 2021. ↩

-

2

For the curious, Waddesdon Manor produced a useful animation taking apart the construction of a similar Riesener commode in the Rothschild Collection, available on YouTube. ↩