The story sounds almost too good to be true. Its ingredients are a boxful of old letters stored in the attic of his house by a bookish and kindly uncle, his sudden death, and a niece who inherits the epistolary bounty. Elizabeth Bowen herself would have hesitated to use something so improbable as the plot for a story, despite her tendency occasionally toward melodrama and always toward the uncanny. Even Henry James, busily stirring the boiling pot, might have balked at the beautiful elaborations of the thing. But Julia Parry could hardly believe her good fortune. Out of her serendipitous heritage, and despite the odd shiver of doubt, she has wrought The Shadowy Third, a marvelous, gently elegiac, beautifully written, and fascinating book.

The letters in question had been stored for years by Parry’s uncle John, son of the Dickens scholar Humphry House. They had been largely forgotten about—“a heart left to beat unheard”—until Parry got unlimited access to them after her uncle’s death in 2011. They were the record of a love affair between Humphry House and Elizabeth Bowen, and were written between 1933 and 1952. Unusually, both sides of the correspondence were preserved, in “large manila envelopes, the texture of old skin.” Humphry’s widow, Madeline, had safeguarded the letters written by Bowen to her husband; after Bowen’s death, Humphry’s letters to her were found by chance in the cellar of a house where she had lived in Oxford and were returned to Parry’s uncle. “The whole relationship,” Parry writes, “was there at my fingertips.” But perhaps not the whole story, for Madeline destroyed a decade’s worth of her own letters, thus partially erasing the third side of the triangle.

The book that Parry has made out of the rich trove she inherited wouldn’t have succeeded, it seems, if Bowen had anything to do with it. Parry cites a number of instances in which an unseen presence sought to hinder her. Shortly after coming into possession of the letters, she attended the unveiling of a memorial plaque at Bowen’s old home in Headington, just outside Oxford. Afterward she went to the Bodleian Library in the city to read about Bowen’s time there:

I plugged in my tablet which started, randomly and furiously, to spit out letters. The keys changed colour as though hit by a ghostly hand…. Among a gobbledegook of symbols, only three words were discernible: “ghost,” “get,” and “out.” I felt a chill on my arms.

As how would she not? Bowen seems to have believed in ghosts, so why shouldn’t she become one herself and fight to protect the privacy of her correspondence? Parry records a less violent but equally unsettling experience when she visits a room in a London lodging house where she thinks House and Bowen may have met clandestinely:

Suddenly I feel a shift in the air as surely as if someone has opened a window. The room’s spirit expands into the dormant space between the tousled beds. It is strong, fierce, bitter. No other place has made my skin tingle like this, robbed me of breath. I feel overwhelmed, almost stifled…. Was this the place they met? I may wonder, but the room knows.

It could be a passage from one of Bowen’s tales of the supernatural, such as the one from which Parry takes her title. Bowen’s story “The Shadowy Third” tells of a marriage haunted by the spirit of the husband’s dead wife. Madeline House was to outlive her husband by many years, but for a long time she had been cast into the shade by his affair with Bowen, one of whose best-known ghost stories is “The Demon Lover.”

As the saying goes, you couldn’t make it up.

Humphry House, whose lasting monument is his edition of Dickens’s letters, completed by Madeline and published after his death, was born in 1908 into a middle-class English family in the town of Sevenoaks in the south of England. He displayed early on a bent for scholarship; as Parry writes, “not many teenagers wish to be excused from cricket in order to read John Henry Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua.”

His mother, to whom he was close, died suddenly when he was seventeen. Bowen also lost her mother when she was young, younger than House was when he lost his; as Parry notes, “both became, at a tender age, motherless children.” House’s relationship with his father, Parry baldly states, was “choked by their shared desire for conspicuous success and financial stability.”

These vicissitudes hardened young Humphry, though his insouciant caddishness, which showed especially in his treatment of women, seems to have been innate. Isaiah Berlin, a close friend of Bowen’s, in a letter to her described House at Oxford, where he went on a scholarship and studied classics and modern history, as “my kind of prig,” adding that what he “fell for” in House was his “splendid reactionary violence, a sort of Fascist sternness which contrasted with the surréaliste undergraduates of my first year at Oxford.” No Sebastian Flyte he, then.

Advertisement

Having tried for a plum fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford, and having failed to get it, House found a job as an English lecturer and chaplain at another Oxford college, Wadham. In those days a Church of England sinecure was still an attractive option for an ambitious young man. But House had Doubts—the word was usually capitalized in those days—which by 1932 had flowered into what Parry describes as “a massive crisis of faith. He railed against ‘a puny pseudo-Christus who was never my God’ and wrote that ‘moods wheel, thicken, multiply, take hideous forms and I want death.’”

At the time he was engaged to Madeline Church, a young woman from his hometown. He informed the college authorities that due to his loss of faith he could no longer serve as chaplain but hoped he would be allowed to stay on as a fellow, which would have given him a living. Wadham had no place for him. Frustrated and close to despair, he turned on his fiancée, dashing off to her an ill-tempered letter: “marry at Christmas or not at all.” Madeline years later wrote: “I decided this was the end. I collected together all H’s letters and every scrap of his I’d got, meaning to burn them!” And then House met Elizabeth Bowen.

Bowen was born in 1899 and was brought up at the family’s ancestral home, Bowen’s Court, near the town of Mallow in the softly rolling countryside of County Cork. The Bowens were Anglo-Irish Protestants, upper-middle-class members of the “Ascendancy” that had established itself in the country over the centuries of English rule since the time of Elizabeth I. The Anglo-Irish were an in-between people, resented if not hated by the largely Catholic native Irish, many of whose forebears had been driven from their land to make way for Protestant “planters” brought over from England under a deliberate policy to Anglicize the country and tap its resources.1 Bowen used to say that she felt her true place was a region of the Irish Sea halfway between Ireland and England.

It was at a lunch party in Oxford in 1933 that she met Humphry House. He was twenty-five, she was nine years older. The lunch was given by Maurice Bowra, a fellow in classics at Wadham, where he later became warden. Bowra, a famous wit, a tireless gossip, and a dedicated bon vivant, is a character out of Trollope or the early novels of Evelyn Waugh. In his memoirs he gave a shrewd portrait of Bowen, from which Parry quotes:

She had the fine style of a great lady, who on rare occasions was not shy of slapping down impertinence, but she came from a society where the decorum of the nineteenth century had been tempered by an Irish frankness. With all her sensibility and imagination, she had a masculine intelligence which was fully at home in large subjects and general ideas, and when she sometimes gave a lecture, it was delivered with a force and control of which most University teachers would be envious.

When she met House, Bowen was an established novelist and short-story writer, and had been married for ten years to Alan Cameron, a civil servant. “Solvent, solid, devoted,” Parry writes, “Alan was good husband material.” The union was what the French nicely define as a mariage blanc: when House first slept with Bowen she was still a virgin, though she didn’t tell him so beforehand. He was quite put out, and in a cross letter to her wrote that he had thought she “had some malformation.”

The Camerons lived contentedly together until Alan’s death in 1952. Such an arrangement was not unusual at a time when often courtship was little more than “a wrangle for the ring,” as Philip Larkin has it, in his poem “Annus Mirabilis,” and marriage frequently a matter of convenience. Bowen wrote to a friend that her husband was, “to a certain extent, like a parent.” It’s possible that he was homosexual. Parry writes that “he was completely committed to their shared life. Nevertheless, there are suggestions that he…enjoyed extramarital liaisons with young men.” Bowen herself had sapphic leanings and spent a memorable night with the young American poet May Sarton at a rented house in Rye, the town on the east coast of England where Henry James, her strongest influence as a writer, had lived. Sarton reported that earlier in her life Bowen “had loved at least one woman, but I gathered that that period was over.”

Advertisement

Freed, supposedly, from his attachment to Madeline, House invited Bowen to come and see him in the village outside Oxford where he was living. A month later, he asked Madeline to visit him, but not on Wednesday, when “I think I shall be tied up with Elizabeth Bowen, novelist.” This smug injunction “demonstrated that,” Parry writes, “the two women were interwoven in the fabric of his life.”

If Alan Cameron was acting in loco parentis to Bowen, she, with her nine years’ seniority and her “fine style of a great lady,” was something of a mother figure for House. In one of Parry’s many felicitous phrases, she was “a woman of the first glance rather than the lengthy stare,” yet she nevertheless directed a long look at the rather bumptious young man in whose company she read Virgil and who dedicated scholarly-sounding poems to her.

She invited him to come as a houseguest at Bowen’s Court, and he accepted in his usual fashion, at once blithe and beady-eyed.2 Nevertheless, on the way to Ireland he stopped off in London, where, as Parry tells us, he likely “once again accepted double bed and board at Madeline’s flat.” Having arrived at Bowen’s Court, a large and impressive but unlovely house, he settled in happily and stayed for months, alone for part of the time, when Elizabeth crossed to London to be with Alan.

She was at Bowen’s Court on the occasion when House made a royal ass of himself. Isaiah Berlin and a group of friends were on a motoring holiday in Ireland and stopped off to stay with him. Among the company was Maire Lynd, known as B.J., whom House immediately fell for, and whom, according to Berlin, he followed about the house “like a huge, lovelorn dog.” The humiliation for Bowen must have been deep, but it would have been as nothing to what she must have felt when the guests departed and House chose to go along with them. He soon returned, no doubt with his tail between his legs. Inevitably, he wrote to Madeline to tell her of the debacle, confessing that his behavior had resulted in his being “severely rated” by Bowen. The scene is easily imagined; surely that day Bowen “was not shy of slapping down impertinence.”

While at Bowen’s Court, House ran low on funds—though what did he find to spend money on, in the depths of the country?—and borrowed from Madeline. Parry writes:

The amount, £8, was not inconsiderable, amounting almost to a month’s pay. While Elizabeth was giving him free accommodation for half the summer, Madeline was helping to subsidise the rest of his stay in Ireland.

He could be insensitive to the point of boorishness. The engagement to Madeline was on again, but he left her in no doubt as to the kind of marriage he—he—had determined they should have. “I cannot cure myself,” he wrote to her, “even now our marriage is settled[,] of violent and casual physical attraction to all kinds of women whom I meet or see…. I may even do sensual acts which are technically ‘unfaithful’ but would you be jealous of those?” In the same letter he asked if she was jealous of his “feeling” for Bowen, whom he had told of his marriage plans—“she says that it makes her extremely happy.” Madeline must have wondered if she was doing the right thing by—in another of Parry’s deft formulations—“leaving Church to become a House.”

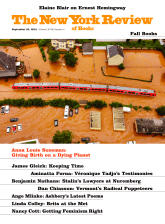

Astonishingly, Madeline agreed to meet Bowen. They had sherry, which was, Parry writes, “the ideal choice for the two women, who shared polite conversation and the same man.” Afterward, House was able to report to Madeline that Bowen thought her “a great girl.” For him, everything was working out splendidly. He sent to Madeline a brisk letter itemizing the “quite definite things” that were to happen on their wedding day in December 1933, including: “5. Short gap for love-making.” Bowen sent House a large studio photograph of herself looking decidedly wistful, “a reminder,” Parry writes, “in gleaming silver albumen, that she still had her eye on him” (see illustration at beginning of article). What Alan Cameron made of all this we cannot know.

Bowen was to remain a presence in the lives of the newly married couple. Madeline must have felt the smart of it, for early on in the marriage she confronted House, asking if he wished for a divorce in order to marry Bowen. He greeted the question with an incredulous burst of laughter. Madeline, mollified, settled down to become the conventional middle-class wife of a university don. “Her skills in the kitchen at marriage,” Parry writes, “extended to the successful boiling of an egg. She needed to learn, fast.” She purchased a copy of Boulestin’s Simple French Cooking, which, the Maître Boulestin recommends, the wife should take to bed with her, in order to learn how to present her husband with a perfect meal when he returns in the evening tired from the office. “Happiness sits smiling at their table.”

All that is required to complete this formula for domestic bliss is the battering of tiny feet, and it was not long before Madeline became pregnant. House didn’t tell Bowen, although she heard it on the grapevine—gossip was one of the chief pastimes of their set. For his part he was not at all pleased “that the child should be coming when I did not intend it: almost against my will,” as he wrote to Bowen. His annoyance at the prospect of becoming a father is understandable if for no other reason than that he already had a son, presumably also without his intending. Little is known of this child except that his mother was another Madeleine, with an extra “e.” House, to his credit—and doesn’t he need it—had told Madeline about the baby, though his coming clean is somewhat tarnished by the fact that he also told Bowen.

A year after the marriage, Bowen went to stay with the Houses at the “isolated, ill-lit cottage” in Devon to which the couple had moved. What a weekend that must have been. Bowen wished to consult House on an essay she had been commissioned to write on Jane Austen. “The two of them would have worked in the high-beamed study,” Parry writes, “the low-slanting February light coming in through the expanse of window.” Through that same window, Madeline recalled years afterward, she glimpsed the two in what was presumably a break from work. Parry describes the scene: “Elizabeth was on her knees in front of Humphry, kissing his hands. Her position was vulnerable, submissive; his more solid, authoritative.” And the wife, the shadowy third, was outside, alone in the wintry air, watching.

Bowen paid another visit to the couple when House returned in 1938 from India, where he had worked for two years as professor of English at Presidency College in Calcutta. By then Madeline had borne two of her three children—one of them was to be Julia Parry’s mother—and was feeling more certain of herself, and of her husband. His time away had cooled the fires of his “feeling” for Bowen, who described the visit in a letter to the novelist and editor William Plomer; her tone suggests that she felt sharply the pangs of a displaced lover. She wrote of

that queer little claustrophobic house of their’s [sic]. It’s really rather touching, that little anxious blond woman and those plain blond babies and the little husky blond nurse—something between a dolls’ house and a rabbit hutch…. I felt rather unhappily uncertain that Humphry would thrive there for long—he seemed to me a bit claustrophobic.

It would not be long before she recovered her self-assurance, and in 1941 she began an affair, her last and possibly the most intense, with Charles Ritchie, an elegant and sophisticated Canadian diplomat stationed temporarily in London. He too was younger than she, though according to Parry they “shared qualities of being outsiders, observers, while moving easily between the worlds they inhabited. Elizabeth referred to them both, almost inevitably, as ‘spies.’”

Madeline too was refashioning her life, or fashioning herself to fit the life she was bound to live. While House was away training to be a soldier during the war, she kept the home fires burning—“Darling, the hens have arrived!”—and homeschooled their children. She went out more into society, making new friends and throwing herself into left-wing politics, though at a local level. And with House she began to assert herself and her individuality. When he remarked in a letter that he happily imagined her “in the old setting, with the old things,” she replied in tones that reveal her new access of spirit and independence: “To hell with the old things and old jobs; they don’t matter a damn. Feeling and thinking can be fresh in spite of them. So please don’t identify me with furniture!” Reading this, one feels like cheering. As her granddaughter writes, “Madeline comes out of the shade in these years in the most compelling fashion. Generous, determined, clever, resilient.”

In 1948 House sought a lectureship at Oxford and went there for an interview. Maurice Bowra invited him to dinner; among the other guests was Bowen. It was fifteen years since the two had first met at this same table. “Now they reprised the occasion,” as Parry stylishly puts it, “with wine in their glasses and water under the bridge.” House got the lectureship and then was asked to edit the complete letters of Dickens, a major undertaking. Madeline was to be assistant editor—unpaid. These positive developments rekindled their love, “and gave Madeline’s considerable intellectual gifts a garden in which to grow.”

By that time Charles Ritchie had married, and once more Bowen was required to step back into the shadows. She and Alan settled in Bowen’s Court at the end of 1951. Alan died the following year. Bowen was alone. Or almost—her affair with Ritchie continued, if sporadically. In 1959, financial difficulties forced her to sell Bowen’s Court.

House worked hard at the Dickens project, through long and punishing hours, which affected his health. One night in February 1955 he suffered a heart attack and died within hours. He was forty-six. In his will he left his estate to Madeline and several items to Bowen, among them a Picasso etching, which later disappeared.

Bowen saw the death notice in the London Times and wrote to Ritchie: “How people come alive, almost unbearably, when they’re suddenly dead.” Bowra wrote to Bowen, lamenting that Madeline “is left with about £200 a year and three children.” House’s publishers invited her to finish the Dickens project, with a salary this time. The first volume was published in 1965, to much acclaim. Meanwhile Bowen found almost a new life teaching semesters at American colleges and getting on the readings circuit, which was still lucrative in those days, and which she delighted in. As Parry writes, when she died of lung cancer in 1973—with Ritchie by her bedside—she was immediately rediscovered by readers and critics. Victoria Glendinning’s fine biography of her was published in 1977.

Madeline, by then in her seventies, began to reread the letters Bowen had written to her husband during the turbulent years of their love affair—if that is what it was, exactly—and what a jumble of sensations she must have felt. A woman of lesser character would surely have destroyed the letters. But she kept them. In her last years she continued work on that other cache of letters, the Dickens ones, “squinnying over the words,” her granddaughter tells us, “right up to her death in 1978.”

In the end she burned her own correspondence of the 1930s, when the affair between her husband and Bowen was at its most intense, but kept those of the lovers. She was, as Parry writes, “both the burner of the letters, and the keeper of the flame.”

This Issue

September 23, 2021

Conceiving the Future

The Well-Blown Mind

Hemingway’s Consolations

-

1

It is said that Nelson’s fleet at Trafalgar was built largely from timber from Irish woods. The mid-nineteenth-century poem “Cill Chaise,” translated from the Irish as “Kilcash” by Frank O’Connor, laments departed glories:

↩What shall we do for timber?

The last of the woods is down.

Kilcash and the house of its glory

And the bell of the house are gone. -

2

When Madeline was on a visit to his parents at their home in Sevenoaks, House wrote from Oxford urging her to “exact a cheque from papa, and do remember to spy round for things we want.” ↩