“I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits,” Thoreau wrote in his 1862 essay “Walking,” “unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements.” Who nowadays feels absolutely free from worldly engagements? Urban Dictionary has the term “goin’ Walden” as “the act of leaving the electric world and city and retreating to the country to obtain spiritual enlightenment or just to reflect for a while. Derived from the unexplicably LONG classic by Henry David Thoreau.”

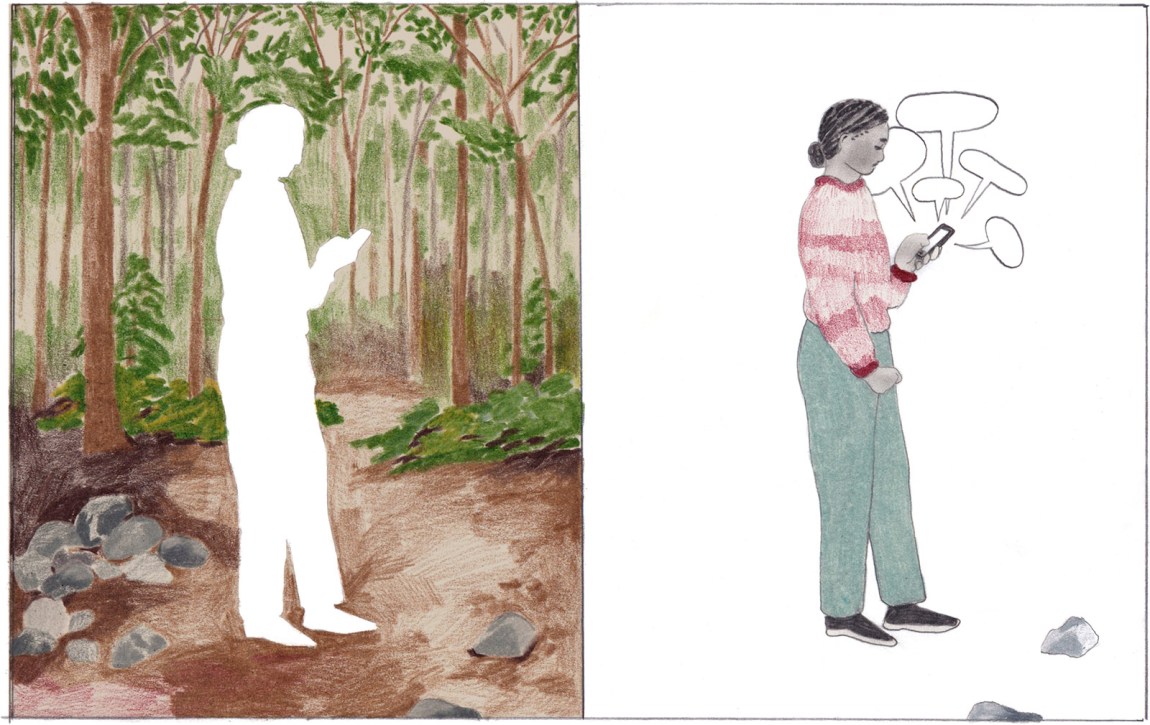

A couple of years ago I took a chance to “go Walden” in person, if not in spirit. Brown University had invited me over from Scotland to give a lecture, and the following day I took a train up to Cambridge to stay with a friend. We left on bicycles the following morning. I don’t remember its taking longer than a couple of hours—wide trails, autumnal forests, glints of rivers, and front yards decked with plastic skeletons for Halloween. By the Mill Brook in Concord we stopped for a sandwich and, a few minutes later, there it was: Walden Pond. I’d expected the woods to be busy, but what I hadn’t anticipated was the forest of arms holding smartphones, taking selfies, engaging in video calls.

“Man is an embodied paradox,” wrote Charles Caleb Colton a generation before Thoreau, “a bundle of contradictions.” Why shouldn’t we create digital experiences of somewhere emblematic of analogue living, or sharable files of a place of disconnection? Rough-hewn stone markers, chained together like prisoners, had been arranged in a rectangle on the site of the great man’s cabin. On one of them sat a teenager, arms outstretched, angling his phone while shouting out to his retreating companions: “I don’t think you guys realize how much this place means to me, I mean, privately.” Later, back in Cambridge, I tweeted some pictures of the place myself.

In his 2010 book Hamlet’s BlackBerry, William Powers suggested that society might benefit from the creation of “Walden Zones”—areas of the home where digital technologies are banned in order to encourage more traditional methods of human connection. Given the ubiquity of devices among modern-day pilgrims to Walden, that ambition seems quaint, even futile.

As a working family physician, I’m shown examples every day of the ways in which new digital technologies are Janus-faced, both boon and curse, strengthening opportunities to connect even as they can deepen a sense of isolation. “Virtual” means “almost,” after all, and was hijacked as a descriptor of the digital world because it was once taken for granted that the creations of Silicon Valley aren’t quite real. Many people now are less sure of the distinction between virtual and actual. After more than a year of pandemic lockdowns through which we’ve all been obliged to meet virtually, I hear more and more patients complain that they emerge from sessions online feeling tense, anxious, low in mood, or with a pervasive feeling of unreality. Virtual connections have sustained us through a time when real interactions were too risky, but it’s worth asking: To what extent do those technologies carry risks of their own?

Susan Matt and Luke Fernandez are a married couple, respectively professors of history and of computing at Weber State University. They describe in their book how every morning for eighteen years they’ve breakfasted together in a house looking out over Ogden, Utah, toward the Great Salt Lake. Back in 2002 they’d listen to the radio and take in the view, then a few years later they added a newspaper but kept the radio going. Now they mostly check the news on their phones. In Bored, Lonely, Angry, Stupid: Changing Feelings About Technology, from the Telegraph to Twitter, they write, “We thought we could take it all in: the view, the news, the radio, our conversation. Our attention seemed limitless.”

But they began to wonder what they had traded for this new habit. Slowly, awareness dawned that the Internet was “changing our emotions, our expectations, our behaviors.” It seemed to offer too much information and too often the wrong information. They’d look at their phones with disappointment when their posts didn’t get the hoped-for attention, or relish the “dopamine fix” when they did. The little screens issued a “siren call” offering freedom to vent anger, which was almost always followed by regret and a nagging sense of frustration.

They knew that the unsettled feelings they were experiencing were nothing new: as far back as 1881 a neurologist named George Beard wrote of an epidemic of “American nervousness” caused by the proliferation of telegraph wires, railroad lines, and watches, all heightened by the “stress of electoral politics,” as if democracy itself were another disruptive human technology. Radio sets, too, were once thought of as an insidious threat to mental harmony: in 1930 Clarence Mendell, then dean of Yale, said that he’d prefer students didn’t bring them on campus (“I believe that life is already too complicated and noisy”). The sensationalism and immediacy of television was at first seen as a destroyer of family rituals—and manners.

Advertisement

So how much of the authors’ anxiety can be explained as middle-aged antipathy to change? Matt and Fernandez’s book is a scholarly attempt to track changes in social norms and in human emotions occasioned by advances in technology across a couple of centuries, but it concludes that our twenty-first-century situation is different from those earlier shifts both in the rate of change and in the problems introduced by cybertechnologies. They set out to examine what they see as a “new emotional style” taking shape, and single out six aspects of human experience for scrutiny: narcissism, loneliness, boredom, distraction, cynicism, and anger.

The word “narcissism” was coined in 1898 by Havelock Ellis—before that “vanity” was more often used, almost always pejoratively. For the average nineteenth-century American, to be vain was to sin against God. But by the mid-nineteenth century the increased presence in middle-class homes of mirrors, and then of photographs, made a virtue of self-regard, and by the 1950s anxiety over being seen as vain was giving way to a powerful social and marketing focus on the promotion of “self-esteem.” Instagram hasn’t done away with the shame of narcissism, it has just transformed it. “Contemporary Americans use social media and post selfies to advertise their success and to celebrate themselves, but they do it with anxiety,” write Matt and Fernandez, quoting interviews with young people who fret ceaselessly over how to get more digital affirmation and who describe their constant posting and “liking” as the most potent ways they have at their disposal to feel as if they exist.

Phones, because they are carried everywhere, have the potential to make us obsess over our own image in a way that mirrors or photographs never could. Of all the mental-health side effects of smartphone use, this, to me, is their most pernicious aspect. The creeping obligation to carry one with you at all times—to be constantly available to your friends and colleagues, to scan QR codes in order to complete basic transactions, to keep track of your step count—means that almost everyone, myself included, now carries a pocket panopticon. Narcissus had to find a pool to gaze into; we just pull out our phones.

The authors offer evidence that suggests the experience of loneliness, too, is being molded by the prevalence of smartphones: firstly by shrinking our capacity to appreciate solitude, secondly by unrealistically inflating our expectations about the number of social connections we should have, and thirdly by implying that “sociable fulfillment is easy, always possible, and the norm.” The ethereal and unreliable connections offered by social media are, for many who end up in my clinic, addictive but deeply unsatisfying. Online relationships don’t assuage loneliness but trap their users in a double bind of “How can I feel so bad if I’ve got this many ‘friends’?”—a bind that has been acutely exacerbated by the enforced isolation of the pandemic. That’s before considering the effect on those who don’t have many online or offline friends, and on teenagers who receive bullying messages through their phones or are socially ostracized. Teenagers now take school bullies home with them on their screens.

In clinic I regularly see kids, both popular and unpopular, who’ve developed the habit of scratching themselves with blades or taking small, symbolic overdoses of medication such as painkillers. No matter how hard I try to convince them otherwise, these young people tell me that the pain and catharsis of self-harm is the only reliable way they have to relieve their distress and to feel they’re really living. Rates of deliberate self-harm among ten-to-fourteen-year-old girls, by cutting or self-poisoning, nearly tripled in the US between 2009 and 2015. Although the ubiquity of smartphones makes it difficult now to establish a control group, there’s gathering evidence that social media use is a major causative factor. Those trends are also found in the UK: in 2019 a paper using data from the prestigious Millennium Cohort Study found that among fourteen-year-old girls, mental well-being deteriorated in proportion to hours spent on a smartphone, with almost 40 percent of girls who used their phones five to six hours a day suffering mental health problems, compared with about 15 percent of those who spent half an hour or less a day on their phones.

Matt and Fernandez also explore evidence of a contemporary decline in the ability to focus attention. They quote Les Linet, a child psychiatrist who studies attention deficit/hyperactivity disorders (ADD/ADHD) and who thinks of the conditions as “search for stimulation” disorders. In this view, sufferers of attention deficit easily become bored and can’t extract stimulation from ordinary environments. Apparently there is now a “boredom proneness scale,” and I wouldn’t be surprised if “pervasive boredom disorder” makes an appearance in lists of psychiatric diagnoses soon. (You read it here first.) In 2012, 11 percent of American youth had been diagnosed with some kind of attention deficit disorder, yet more than a quarter of college students at that time used drugs for the condition without prescriptions, as study enhancers.

Advertisement

The line between what constitutes clinically significant attention deficit and the heightened distractibility of the smartphone age is blurred, complicated by the increasing social expectation of access to psychiatric drugs based on desire and preference rather than clinical need—an expectation that makes the condition routinely overdiagnosed. My practice sits beside the University of Edinburgh, and every exam season I meet students who’ve noticed just how many of their American peers turbocharge study sessions with Ritalin and Adderall, and have approached me for a formal diagnosis so as to be eligible for a legal prescription and not miss out. “In the attention economy,” write Matt and Fernandez, “the chief means for making profits is through distraction. Because these distractions have become integral to the business process, they are at once vastly more ubiquitous and much more entrenched.”

Maël Renouard, a French novelist, translator, and former political speechwriter, is more hopeful and celebratory. For him the Internet is a playground rich in human possibility, but at the same time he is overwhelmed by it, worshipful in his admiration the way someone in the Middle Ages might have been overawed by a cathedral. His book Fragments of an Infinite Memory offers a series of thought experiments on the possibilities of online connectivity, winging the reader on flights of fancy that circle around the Internet’s impact on academia, our social lives, and its near-limitless capacity to fuel both nostalgia and the search for what’s new. It’s allusive and full of unexpected digressions, structurally experimental and ironic.

Renouard opens with the idea of googling what he’d done one recent evening, aware that most of his activities leave a digital trace and his life is entangled in so many clicks, page views, and unseen cameras that his experience of reality has been transformed. He marvels at the quantity of material that historians of the future will have to exploit, observing that “Claude Lévi-Strauss says somewhere that even two or three minutes of film recorded by a camera placed in the streets of Pericles’s Athens would be enough to overturn our entire historiography of antiquity.”

Googling yourself is a notoriously perilous activity, and Renouard tells a story attributed to Pliny the Elder of how new Roman emperors would have a carnifex gloriae (a butcher of glory) whispering “Remember that you will die” to them as they were carried through cheering crowds. “We, too, have our carnifices gloriae interretiales,” Renouard writes. “Every individual who attains the least bit of notoriety is sure to see, on the internet, a few not very obliging comments attached to his name.” And we no longer have the touching faith of the early years of the Internet, when it was believed that anonymity would facilitate sincerity—it’s clear now that it accelerates the reverse.

Renouard picks his way through the transformations wrought by Web culture among his own milieu, the French elite of the École Normale Supérieure. For him and his friends, merely sending someone a paper letter has become a sign of exceptional magnanimity, “like spontaneously offering a cigarette to a stranger”; but he remembers how until very recently, for academics, there was still “something almost shameful in resorting to the internet,” comparable to an athlete’s use of doping. One of many startling episodes explores the revolutions in perspective offered by tools like Google Maps, which allow the user to switch between walking, cycling, and driving when planning a route:

Whenever I hit the wrong button and ask how much time it would take to walk from Paris to Marseille or La Rochelle, and the machine calculates the number of days required for such a trip, extravagant in our times, I feel as though I’ve suddenly been transported to the Middle Ages, or into Marguerite Yourcenar’s The Abyss—and if my finger accidentally selects bicycle, silhouettes from 1940 appear in my mind’s eye, as if our technical capacities had carried us to the top of a kind of watchtower, from which we could look back on the most distant past and see it rise at the end of the landscape behind the last line of hills, like a troupe of minstrels, guildsmen, or penitents pursuing their long migrations through the forests and fields of Europe.

For Renouard, we are seeing the end of a civilization built and sustained by paper. Though reports on the death of the book have been repeatedly exaggerated, Renouard is adamant that we are all witness to that civilization’s passing, just as our great-grandparents were witness to the death of a world dependent on the strength, speed, and servitude of horses. “Books will never completely vanish,” Renouard writes, “just as horses are still around, in equestrian clubs, where they are objects of aesthetic worship and enjoy a level of care whose technical precision verges upon a science.” The books we love will become luxury items to be cherished, but corralled into artistic, leisurely circles.

The other day I tried giving a friend of mine a DVD of a movie I thought she’d enjoy. She looked at me blankly. “A DVD?” she said. “Do you guys still have a player?” It put in mind the millions of tons of DVDs now sedimenting slowly into the Anthropocene strata of the world’s landfill dumps, pushing down on the CDs, themselves piled over VHS and Betamax cassettes, LP and gramophone records. Owning a book for its beauty is one thing, but owning a book for the information it holds? Why would you? Not when Google has promised to “organize the world’s information” for the price of your advertising preferences.

And photography? Renouard quotes his friend B., who’d just returned from a trip touring Tunisia and hadn’t taken a single picture. “I told myself, more or less consciously,” B. said, “that I could find on Google Images as many representations as I liked of the places where I went, with an ease directly proportionate to the beauty of the place.” “More or less consciously” is an insight to savor, illuminating how deeply digital possibilities are able to reorganize our thinking. This change didn’t feel like an impoverishment but an enrichment: “I was glad to be fully present to the landscapes,” B. explains.

This, then, is the great liberation of Renouard’s Internet—a limitless provider of auxiliary memory, a robotic prosthesis we carry everywhere with us. Our phones might be silently counting our steps in our pockets, but it’s a door in our minds they’ve kicked open—a door that leads directly into the World Wide Web. Fragments of an Infinite Memory began, Renouard writes, with the “daydream that one day we would find on the internet the traces of even the most insignificant events of our existence,” as if “the internet was simply the medium that gave access to Being’s spontaneous memory of itself.”

But for all his tech-savvy optimism, the ease with which he slips into this new medium, Renouard ultimately shares the fears of Matt and Fernandez: human capacities are limited in comparison with the digital edifice we have built. We are “fragile beings in a kind of ontological backwater,” ill-adapted to the speed and possibility of what until twenty years ago was still called an “information superhighway.” We don’t call it that anymore because it reifies something that is no longer extraordinary. Indeed, that “superhighway” dominates and overlooks our lives and our minds, so tattered and vulnerable, “like an old neighborhood in a vastly expanding city.”

Renouard thinks that digital natives who have always known an Internet wouldn’t even notice the way older, shabbier media are being crowded out and, when those media are gone, are unlikely to feel they’ve lost anything. For the new generation, their “real” memories will be precisely those that have left a “virtual” trace: the

fragility of personal memory is limited to those amphibious beings who have lived a significant portion of their lives before the advent of the internet…. Perhaps those who grow up with the internet will leave enough traces of themselves to find their way through their own memories without fail.

For Renouard, the steadily shrinking neighborhood of his old “amphibious” order feels as if it’s under siege.

If Matt and Fernandez are the Priams of this siege, offering wise and cautious counsel, Renouard might be the Paris, the bon vivant happy to sleep with the enemy. Howard Axelrod, then, is its Cassandra—uttering calamitous prophecies of imminent techno-apocalypse, unheeded. In his book The Stars in Our Pockets, Axelrod notes that he declines even to make use of a cell phone, and reports a conversation he had on a date with an exasperated woman who tells him “even homeless people have smartphones”:

I didn’t know how to explain that I wasn’t afraid of iPhones but of phone eyes, of having to adjust to yet another way of orienting in the world. I made an overdetermined joke about no one needing a writer to administer a semicolon in an emergency, received no response, then said something about loving airports as a kid, people always arriving from afar, each gate a portal to a different city, the feeling of the whole world brought closer together, but that as much as I still enjoyed passing through airports, I wouldn’t want to feel as though I was living in one.

It’s a beautiful moment, elegantly expressed, Axelrod managing to communicate both the strength of his conviction and the difficulty of persuading others to share it.

The Stars in Our Pockets explores his anxiety over what phones are doing to our brains, and builds on the success of his 2015 memoir The Point of Vanishing, an account of his two-year retreat into the Vermont woods after an accident in which he lost sight in one eye. His partial blinding occasioned a reckoning, a recalibration with the world.

Near the beginning of The Stars in Our Pockets, Axelrod lists some of the more worrying studies he has read of the effects of the digital revolution on human experience and interaction. Online connectivity has diminished our ability to empathize (“down 40 percent in college students over the past twenty years,” according to a meta-analysis in Personality and Social Psychology Review) and has made us intolerant of solitude. (Given a choice of doing nothing for fifteen minutes or giving themselves a mild electroshock, nearly half of the subjects in one experiment chose the distraction, according to an article by Timothy D. Wilson in Science.) For Renouard, to look into the transport options on Google Maps was to have his historical consciousness expanded, but for Axelrod, those same maps are a value system that deceives the user into thinking himself or herself at the center of the world. He quotes studies showing that GPS users have poorer memories and spatial orientation, and recounts the now familiar repercussions of overreliance on satellite navigation: those stories of people who’ve driven off a cliff or into a field, or who set out for a town in Belgium and followed their GPS all the way to Croatia.

On the subject of the deleterious impact of digital connectivity on mental health, he cautions that, although correlation is not causation, “suicide among American girls has doubled in the last fifteen years.” Jean Twenge of San Diego State University published a sobering review of the psychiatric literature last year, finding correlations between smartphone usage among teen girls and young women and declines in measures of their happiness, life satisfaction, and “flourishing.” Twenge also found plenty of evidence to suggest that smartphone usage has something to do with increases in

loneliness, anxiety, depressive symptoms, major depressive episodes in the past year, hospital admissions for self-harm behaviors (nonsuicidal self-injury), suicidal ideation, self-harm and suicide attempts via poisoning, suicide attempts, self-reported suicidal ideation, and in the suicide rate.1

The connection was also present, but weaker, for teen boys and young men. It’s worth pointing out that other studies, including a major report in 2019 by the UK’s Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health, have not found the same correlation, and that in those studies that do show a harmful effect it has been difficult to establish the extent to which social media use is the problem or whether other uses, such as gaming, also contribute.

Twenge proposes a variety of mechanisms for the smartphone effects she cites, most notably the displacement and disruption of face-to-face social interactions, phones’ capacity to interfere with sleep, their facilitation of cyberbullying, and the opportunities they offer to learn about modes of self-harm.

The value systems built into our phones are anything but neutral. Early in the digital revolution a relatively small group of people decided that algorithms would be tailored to drive maximal engagement with social media, regardless of content, that search engines and social media themselves would be almost entirely funded by advertising, and that this advertising would be targeted with the aid of relentless online surveillance. Axelrod’s book reminded me of Radical Attention, a recent book-length essay by Julia Bell, who laments the way that the Internet as we know it is largely the product of one place and one demographic group,

predominantly white men of a certain class and education who lived (and live) in the glare of the Pacific light of Silicon Valley, influenced by the mixture of hippie idealism, Rayndian [sic] libertarianism, and gothic poverty that defines California.2

The Internet could have been otherwise, and if Silicon Valley or its competitors can be shaped by a greater diversity of voices, it might yet be.

The Stars in Our Pockets isn’t really a memoir or a polemic but a sequence of meditations on what we risk losing as we offer phones ever more control over our lives. It’s less playful than Renouard’s book, less substantial than Matt and Fernandez’s, but more intimately personal than either. Axelrod describes turning off an app like Twitter and feeling “a queasy sense of leftover energy, of having been tricked into throwing punches in the dark.”

Virtual realities are a poor substitute for human engagement, and almost by way of contrast, Axelrod describes a vivid, transcendent encounter he had with an old flame in the woods around—wait for it—Walden Pond. The couple walked around the water, reflecting on life, their advancing age, the contracting time that each of us has left, and the imperative of choosing wisely what we do with it. Elsewhere Axelrod quotes William James: “Each of us literally chooses, by his ways of attending to things, what sort of a universe he shall appear to himself to inhabit.”

We can’t say we haven’t been warned. When patients come to my clinic for help with alcohol, I explore what their life might be like without that drug, and whether they’re prepared for whatever demons might emerge when they get sober. Since these three books were published, the forced distance of the pandemic has obliged all of us to connect digitally, and now it’s common to see people with a different kind of dependency: strung out with Internet anxiety, sleepless with digital overload, having difficulty distinguishing between what’s real and what’s virtual, and not knowing what their life would be without the Internet. My advice? It has never been more important to make time to find out.

This Issue

September 23, 2021

Conceiving the Future

The Well-Blown Mind

Hemingway’s Consolations