In response to:

The Triumph of Mutabilitie from the July 1, 2021 issue

To the Editors:

There is a list in Catherine Nicholson’s article on Edmund Spenser [“The Triumph of Mutabilitie,” NYR, July 1] of writers who found The Faerie Queene ponderous. The concluding witness is Virginia Woolf: “To those eager to cultivate an appreciation for Spenser, she counseled, ‘The first essential is, of course, not to read The Faerie Queene.’”

It is not a made-up quotation. All twelve words are there. You can find it in The Moment and Other Essays (published in 1947). Here’s Virginia Woolf at more length:

The first essential is, of course, not to read The Faery Queen. Put it off as long as possible. Grind out politics; absorb science; wallow in fiction; walk about London; observe the crowds; calculate the loss of life and limb;…and then, when the whole being is red and brittle as sandstone in the sun, make a dash for The Faery Queen and give yourself up to it.

There is a more quotable passage later in the essay when she sums up Spenser’s charm:

It is a world of astonishing physical brilliance and intensity; sharpened, intensified as objects are in a clearer air; such as we see them, not in dreams, but when all the faculties are alert and vigorous.

One tone-deaf moment in a three-page article is slight, almost too slight to mention, but the misleading quotation certainly makes Virginia Woolf sound dismissive and obtuse. I don’t know whether I am writing to defend Spenser’s reputation or hers.

Michael Beard

St. Paul, Minnesota

Catherine Nicholson replies:

It’s true: the passage containing the line I quoted from Woolf builds to quite a ringing endorsement of The Faerie Queene, a work she avoided for decades and was surprised, late in life, to discover she enjoyed. I regret not having had space in this piece to explore the complexity of that readerly relationship. But I don’t think the quote on its own is misrepresentative, for Woolf never fully relinquished her ambivalence toward Spenser’s creation, whose brilliance and dreamlike intensity were inseparable, she thought, from an “indistinctness which leads, as it undoubtedly does lead, to monotony.”

In her reading journal, Woolf records both the exact day she realized she liked The Faerie Queene—January 23, 1935—and the day, five weeks later, when she was overcome by “a strong desire to stop reading [it].” “As far as I can see,” she writes, “this is the natural swing of the pendulum.” In my view, that’s the value of the line I quoted: when Woolf says that not reading The Faerie Queene is essential to admiring it, she doesn’t just neatly sum up a venerable tradition of hating on Spenser’s poem; she also illuminates the dialectic of frustration and fascination, obsession and wariness, that is so peculiarly characteristic of its effect even on those who adore it.

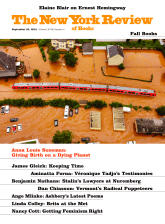

This Issue

September 23, 2021

Conceiving the Future

The Well-Blown Mind

Hemingway’s Consolations