The word “moderate” may not apply to Andrew Cuomo’s intemperate personality, ham-fisted confidence, and occasional displays of megalomania, but a moderate Democrat par excellence is what the former New York governor was. He was a master centrist, playing both ideological sides of the Democratic Party, passing antidiscrimination laws for gay New Yorkers and boosting the state’s minimum wage to $15 per hour with one hand, while opposing increased taxes for the superrich with the other.

He was a brilliant consolidator of his own power. During his first eight years in office, from 2011 to 2019—his most dominant period as governor—he rammed through the legislation he wanted and killed what he or his donors disliked, counting on the votes of eight obedient conservative Democratic senators to block bills advanced by the progressive wing of the party. He exercised almost total control over the state budget and thwarted corruption investigations that threatened his administration. Cuomo strong-armed rather than cajoled; he used intimidation rather than seduction to get his way. After his grip on the legislature loosened in 2018 with the electoral defeat of six of those senators, he showed his pragmatic side, refraining in 2019 from vetoing a popular rent control bill that restored critical tenant protections, even though it offended members of the real estate industry who had helped finance his campaigns.

In the spring of 2020, with Covid-19 deaths at their peak in New York and millions of residents bunkered in their homes in a state of dread, Cuomo began a series of daily televised briefings, forging the kind of intimacy with voters that politicians rarely achieve. Praised for being a counterweight to President Trump,* who was fixated on fraudulently minimizing the infection numbers, Cuomo became a beloved national figure. There he was, every day at noon, a most improbable consoler, frantically trying to prevent the state’s hospital system from collapsing, worrying about the health of his elderly mother, the former First Lady of New York, and offering his own confinement with his daughters in the Executive Mansion as emblematic of New Yorkers’ trials. He seemed to perform feats of political wizardry, wresting from the federal government thousands of ventilators and gaining approval for a pop-up hospital at the Javits Center in Manhattan. He managed to wrangle clearance from the White House to allow New York to conduct its own Covid tests, when Trump was still limiting them to people who had been in China and were actively showing symptoms.

For Cuomo, rewards quickly followed: a $5.1 million book deal about his “leadership lessons” from the pandemic and an Emmy Award for his briefings. Cuomo “effectively created television shows, with characters, plot lines, and stories of success and failure,” said the head of the Television Academy, as if his press briefings had been a limited dramatic series.

Last February, after the governor’s most senior aide, Melissa DeRosa, blurted out that the state had withheld the number of Covid deaths in nursing homes in order to avoid investigation by Trump’s Department of Justice, Cuomo’s shine dulled considerably. Assemblyman Ron Kim of Queens revealed that after he publicly questioned the governor’s nursing home policies, Cuomo phoned him, saying he would “destroy” Kim’s career if he didn’t sign a statement in support of them. During the following days, according to Kim, disturbing calls poured in from Cuomo’s aides. Kim felt threatened enough to hire a lawyer.

By then, the first of what would become a deluge of sexual harassment accusations against Cuomo had already been made public. For the first time since he took office there was more political capital to be gained by defying the governor than obliging him. Resentment on the part of legislators had been simmering for years.

Kim was able to garner enough support in the State Assembly and Senate to revoke the immunity against legal action for negligence and wrongful death that Cuomo had granted to nursing homes during the early days of the pandemic. Sixty-five percent of nursing homes are private, for-profit businesses. There is evidence that Cuomo’s order to discharge elderly hospital patients to these homes boosted their profits: during the period that the order was in place, about six thousand new patients were sent to them. Most of these patients had Medicare, which reimburses the homes at a higher rate than their other residents pay. The Greater New York Hospital Association, a trade group that represents operators of nursing homes and hospitals, has donated more than $2 million to Cuomo’s campaigns. The group had boasted that it “drafted and aggressively advocated” for the immunity law.

Cuomo’s argument that he had no choice but to make room for the onslaught of Covid patients in overcrowded ICU wards has some merit. But it is clear that many of those elderly patients did die of Covid in nursing homes, and that the state was deceptive about the numbers. The political damage was severe. The emboldened legislature stripped him of the emergency powers it had granted him at the beginning of the pandemic, a humiliating blow.

Advertisement

Still, nothing was more disabling than the accusations of sexual harassment. “I felt completely violated,” said a female state trooper about Cuomo’s running his hands over her body. “I was scared and I was uncomfortable,” said a former aide whom he groped. And on the accusations went. It was obvious that the governor’s bullying of elected officials like Kim extended to his own staff, and that this included the sexual intimidation of young women in his office—all of it facilitated by a small coterie of loyal senior advisers.

Yet in August 2019—surrounded by women’s rights activists—Cuomo had signed into law a stringent bill to combat sexual harassment in the workplace. The scandal carried echoes of Eliot Spitzer, who as New York’s governor in 2007 passed the toughest anti-sex-trafficking law in the nation, criminalizing johns rather than the prostitutes they hire. Spitzer was forced to resign in 2008 when he was caught paying escorts for sex. The paradox in both cases seems pathetically banal: power provokes a recklessness in some that they cannot curb. Both men may have intended to shield women from impulses they knew all too well in themselves, while at the same time shielding themselves from suspicion with policies designed to outlaw those impulses.

As the number of accusers mounted early this year, Cuomo took cover behind New York attorney general Letitia James’s unfinished investigation into their claims. “Wait for the facts” was his temporary defense. He still had enough influence among legislators to keep impeachment hearings from proceeding. His endorsement of James had been crucial to her election in 2018; in the primary she had been seen as the moderate candidate. He may have believed that her report would, if not vindicate him, at least give him the benefit of the doubt. But when it was released on August 3, he was portrayed as a serial sexual harasser and workplace abuser who, in the attorney general’s words, “had violated federal and state law.”

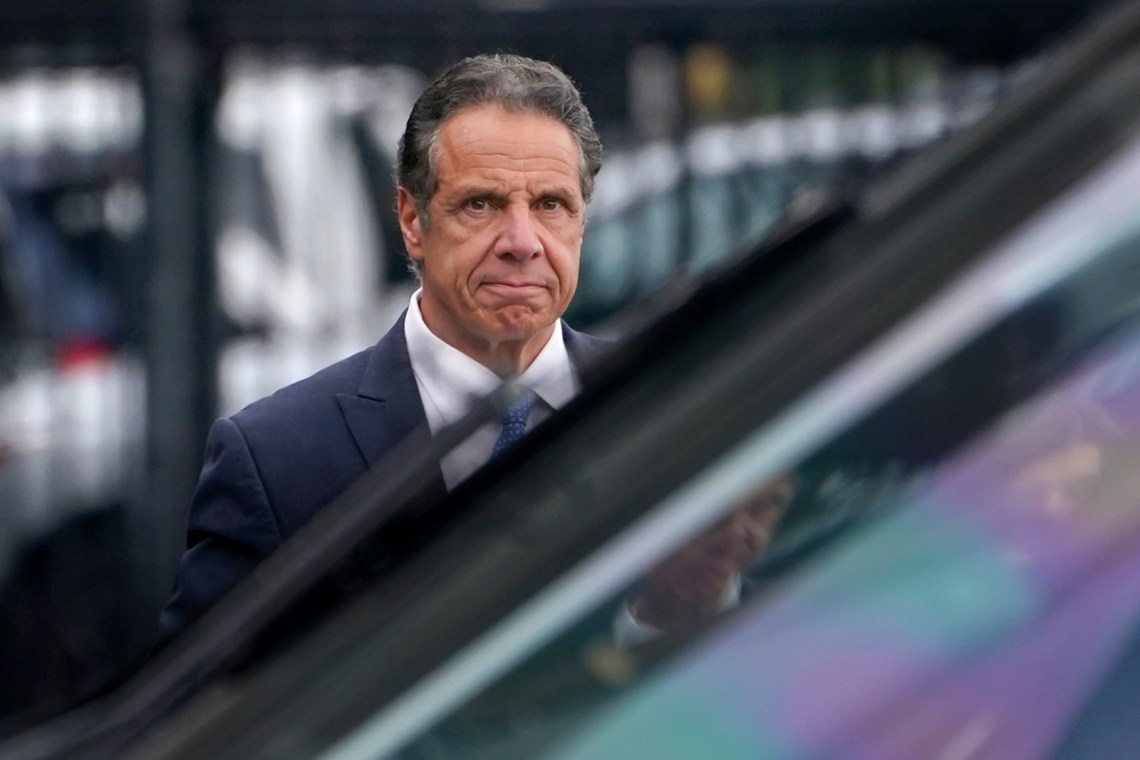

It took only a week for Cuomo to realize that if he didn’t leave office voluntarily, the State Assembly would impeach him. During the speech on August 10 in which he announced that he would resign in fourteen days, he appeared ravaged and cornered, his face creased into what looked like a stunned scowl. His tenacity provoked the kind of sympathy one might feel for Grendel, the beast in Beowulf: “Spurned and joyless his days of ravening had come to an end.” Like Grendel, he “waged his lonely war.” He projected the wounded bewilderment of an innocent man whose selfless devotion to the common good had been denigrated and mocked. “I thought a hug…was friendly,” he said. “I kissed a woman on the cheek…and I thought I was being nice.” He admitted that he was not an easy person to like: “My sense of humor can be insensitive and off-putting.”

But this abrasiveness, he implied, was one of the attributes that helped him serve the people of New York. “You know me,” he said, talking directly to voters who had elected him governor three times. “I love you. And everything I have ever done has been motivated by that love.” The attorney general’s report, he said, was “unfair” and “untruthful.” If everyone was held to the standards he was being held to, he seemed to be saying, society could not function.

During his final day in office, Cuomo broadcast a “farewell” address that seemed designed to position him for another run for governor. Bitter in tone, with a barely suppressed rage, it had all the trappings of a campaign speech. He talked directly to voters again, this time affecting an almost conspiratorial fellowship. He credited New Yorkers for his accomplishments; he was no more than the vessel of their wishes for a higher minimum wage, for a ban on assault weapons, for LGBTQ equality. “I went to you,” he repeated in a stiff, passionate, staccato rhythm, “and you did it. You made the right decision.” He savaged progressives for their “misguided and dangerous” desire to defund the police and for “demonizing business,” while christening himself the most progressive governor in the country. In a jarring non sequitur that seemed to promise a glimmer of self-reflection, he said, “There are moments in life that test our character, that ask us, are we the person we believe we are?” But he immediately retreated from the question. There would be no theater of contrition from Cuomo.

The Democratic primary for governor will be held next June. Surely Cuomo will dip into his $18 million campaign war chest to conduct private polling and gauge his chances for reelection, which at the moment are extremely unclear. If he runs, he will be banking on a depth of voter attachment more common to a caudillo than to a battered politician offering competence and experience as his main qualifications.

Advertisement

Could he win? There are signs that his support among Black voters is still strong. Congressmen Gregory Meeks, who represents predominately Black working- and middle-class sections of Queens, and Hakeem Jeffries, who represents eastern Brooklyn, were among the last top New York Democratic officials to concede that Cuomo had to resign. Even then their criticisms were muted, an acknowledgment that large swaths of their constituents remain loyal to Cuomo. “There are many people in the communities that I represent, some of the hardest parts of Brooklyn, who believe that Gov. Cuomo was there for them in the context of the pain, suffering, and death” of the pandemic, said Jeffries. Meeks praised Cuomo for what he did “in regards to infrastructure and building”—state construction projects at JFK Airport provided well-paid jobs in his district.

Eric Adams’s victory in the New York City mayoral primary was a positive omen for Cuomo. It revealed the quiet existence of a kind of New York profonde, consisting of moderate working-class voters numerous enough to propel a candidate into office. Cuomo’s downstate support overlaps with that of Adams. And he may find solace in the fact that New Yorkers have shown a willingness to overlook outright corruption in his administration: in March 2018 his closest aide was convicted of soliciting and accepting bribes; seven months later Cuomo was reelected with nearly 60 percent of the vote. He may reasonably calculate that with a coalition of Blacks, LGBTQ voters who remember his legislation for gay rights, service and warehouse workers who give him credit for raising the state’s minimum wage, and voters loyal to him for his Covid briefings, he can squeak out a plurality in the primary, as Adams did in the first round of the ranked-choice vote in New York City.

Older voters will be crucial to his chances, and anecdotal evidence suggests that at least some of them, no matter their gender or ethnicity, accept his explanation that his uninvited sexual advances were nothing more than an innocent generational misstep. One far-fetched conspiracy theory making the rounds on Twitter and elsewhere is that Trump framed Cuomo in order to get a Republican governor in office who would pardon him of any state charges resulting from investigations by James and the Manhattan district attorney’s office.

More unpleasant news, however, may lie in wait for Cuomo. The Albany sheriff is actively investigating a groping charge against him—a criminal misdemeanor. One of his accusers, Lindsey Boylan, has announced her intention to file a civil suit, and some of the others will almost certainly do the same. Federal prosecutors are looking into the nursing home scandal, and the previously toothless Joint Commission on Public Ethics has announced its intention to disinter more of the ex-governor’s sins.

In addition, Cuomo’s Emmy was rescinded, a small cut perhaps, but one that emphasizes to voters that he is a social pariah. The attorney general’s office is investigating the work of state employees on Cuomo’s book, another potential violation of ethics rules. Taken together these inquiries may solidify an insuperably malignant portrait of Cuomo and bring his political career to an end.

One would think that Cuomo’s demise might provide an opening for progressives in New York, but as of now there’s little indication that this is the case. Despite the surprising nomination last June of a socialist for mayor of Buffalo on the Democratic ticket and some notable electoral victories in New York’s City Council elections and in the citywide race for comptroller, the highest state offices appear out of their reach. During the mayoral primary, progressives’ most appealing policies—on affordable housing, education, health care, and taxes—got lost in the debate about policing.

At the state level, a housing activist with knowledge of Albany I spoke with could count only eight reliable progressives in the Senate (out of a total of sixty-three senators) and sixteen in the Assembly (out of a total of 150 members)—too few to dictate policy or even to form an effective caucus. Remarkably, what has happened in New York is that grassroots activists have pushed cautious, status-quo-minded legislators to the left on selected issues, such as housing. Tenant protection measures that were considered unspeakably radical four years ago are now openly promoted in both chambers.

A plethora of gubernatorial candidates from every point in the party’s spectrum are likely to emerge. The most serious obstacle to any of them is Kathy Hochul. The new governor is already in campaign mode. Hochul’s first task has been to show voters that she’s at least as competent as her predecessor, without his darker impulses. Her second task is to convince New York City voters that she will defend their interests. Hochul’s history is that of a conservative Democrat from Erie County, where she was obliged to walk a narrow political line. In 2007, as Erie County clerk, she grabbed headlines by taking an unsavory position against then governor Spitzer’s proposal to grant driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants, declaring that immigrants unable to produce a social security card with their application would be arrested and possibly thrown out of the country. When she took office as governor on August 24, she immediately switched gears: undocumented immigrants who did not qualify for federal help, she told The New York Times, would become priority recipients of state aid.

To Hochul’s credit, she successfully called an emergency legislative session to write a new law to extend (until January 15, 2022) a moratorium on evictions for nonpayment of rent. This replaces a previous law that the US Supreme Court had struck down. The law will stave off what threatened to be a catastrophic explosion of the city’s homeless population. Presumably landlords will be compensated from the state’s share of the federal government’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program, the disbursement of which the Cuomo administration bungled badly. The private company Cuomo contracted to administer the funds did such a poor job getting checks to needy renters that at the time of his resignation less than 5 percent of the money had been distributed, another dent in Cuomo’s reputation for competence. Hochul appears to have taken effective action to speed up the process.

Unlike Cuomo, Hochul has been making herself available to legislators and county executives, who clearly enjoy the shift of power in their direction, as she works to build support among the middle echelons of the party. She has been ubiquitous in New York City. On August 29 she popped up at a Manhattan subway station to express her outrage at a power failure that stranded riders. She explained what caused the failure in the language of an electrical engineer, displaying knowledge of a transportation system whose budget and management are now under her control. The performance provided another contrast with Cuomo, who had the unnerving habit of disparaging the subway as filthy and unsafe, as if he had no responsibility for its condition. Four days later she appeared with Mayor Bill de Blasio following the ravages of Tropical Storm Ida, though their briefing mostly highlighted the state’s helplessness.

A Cuomo candidacy next year would rive Democrats. One can imagine him in the primary, an enraged outcast emotionally pleading his case and hungry for vindication. To ward him off, the State Assembly might conduct retroactive impeachment proceedings, which, if successful, would bar him from holding state office for life. Cuomo, for his part, might dispense some of his campaign money to legislators fighting for reelection—the time-honored practice of sugaring potential opponents.

In any scenario, the realities that ordinary New Yorkers face—a public education system beleaguered after a year of remote learning, the stress of enormous numbers of small-business bankruptcies, the struggles of the restaurant and service economy, the devaluation of half-empty office towers, a persistently high Covid infection rate, homeless emergencies in New York’s largest cities, and the vulnerability of much of the state to deadly hurricanes and storm surges—seem beyond the corrective powers of a single politician. What is certain is that, with or without Cuomo, the future direction of New York’s Democratic Party, and by extension New York State, is up in the air.

—September 9, 2021

-

*

Including by me in these pages: see “Emergency Responder,” May 14, 2020. ↩