“The wholesale murders going [on] now in Paris are heartrending.” Charles Darwin received this news in a letter from the paleontologist Vladimir Kovalevsky, dated May 28, 1871, the final day of a week known since as the Semaine sanglante. Two months earlier, socialist revolutionaries in the French National Guard had seized the capital and declared a social-democratic government, the Paris Commune. The young Third Republic government had moved to Versailles. Now the Versailles army, having defeated the Communards, was summarily executing hundreds of people, lining them up against stone walls and shooting them.1 Today, along walls in the Luxembourg Gardens and Père Lachaise cemetery, you can still see the bullet holes.

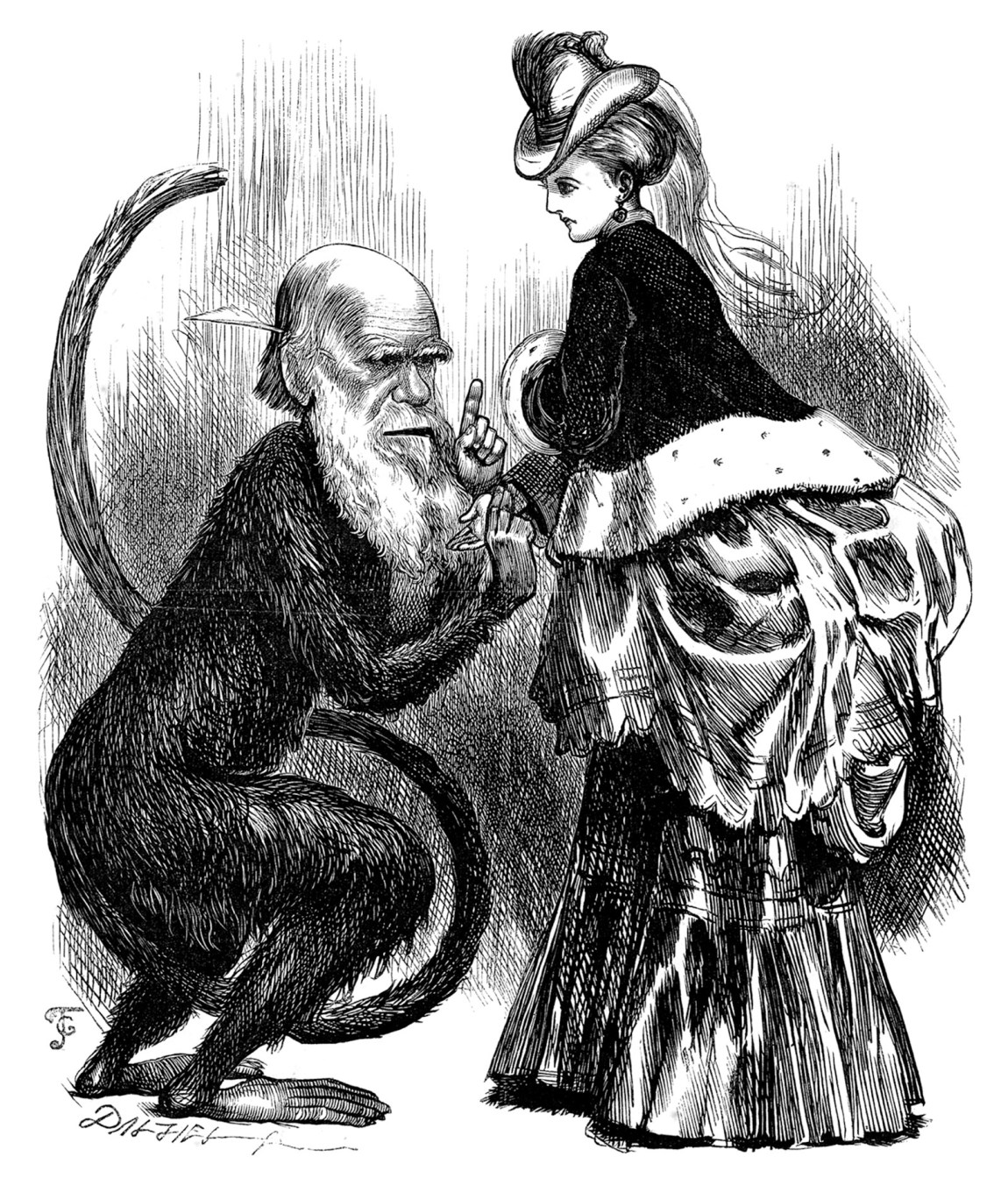

Darwin had just published The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. After hesitating for more than a decade, he had applied his evolutionary theory to humans. But the book was undergoing a “fiery ordeal,” as he said, and looked in danger of becoming another victim of anti-Commune outrage. An anonymous reviewer for The Times ominously connected Descent with the ideas of the Revolution-era French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, author of the first fully elaborated evolutionary theory. Look, the reviewer insinuated, where that irreligious, materialist theory had led: to revolution, Jacobinism, regicide, the Terror! From the Revolution onward, conservatives in France and abroad had identified Lamarckism with political radicalism. The Times reviewer now accused Darwin, like Lamarck, of promoting “disintegrating speculations” that undermined moral authority and social order, loosed “the tempests of human passion,” and unleashed the “most murderous revolutions.” In France, history was repeating itself; for Darwin to publish his book “at such a time” was “more than unscientific—it is reckless.”

French politics had haunted Darwin from the start. The momentous idea that living forms emerged over time through a process of self-transformation had originated not only in the writings of French Enlightenment authors such as Lamarck, but in those of Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus Darwin. The elder Darwin had been a doctor, naturalist, poet, libertine, abolitionist, republican, and admirer of the revolutionaries in France, for whom he wrote some heroic verses in 1791. But Charles Darwin, who had spent his career struggling to domesticate the idea that life had emerged by a natural, gradual process, disavowed any inheritance of revolutionary or Francophile tendencies. “I quite agree with you about the savage brutality of the Versailles army,” he responded carefully to Kovalevsky, “but on the other hand I must think that the Communists have made themselves everlastingly infamous.” Still, in English polite society the idea of evolution continued to sound suspiciously French, carrying a sulfurous whiff of Jacobin revolution, to which the spring of 1871 added communism.

The reviewer for the Pall Mall Gazette was more sympathetic than the Times’s to Darwin’s book. Though his review was also anonymous, the author revealed himself to be the politician and journalist John Morley, who wrote to Darwin in commiseration: “I don’t know whether you are indignant or amused at writers who call you reckless for broaching new doctrines…at a time when Paris is aflame, and we have republican meetings in the Old Bailey.” (The republican meeting in question had actually taken place at St. James’s concert hall, a less alarming venue than the criminal court.) Morley didn’t accuse Darwin of sowing chaos, but he did think Darwin went too far in another respect. Morley’s complaint concerned Darwin’s theory of “sexual selection,” in which animals choose mates based on their ideas of beauty, and these choices, accumulating over generations, produce striking features such as the peacock’s tail. While some animal features such as peacock feathers or the nightingale’s song might seem beautiful, Morley objected, what about the macaw with its “harsh screeching” and “horrible contrasts of yellow and blue”?

What’s wrong with yellow and blue? That would’ve been my reaction, but Darwin just explained that he thought animals had their own senses of beauty, not necessarily corresponding to human tastes. “When an intense colour or two tints in harmony, or a recurrent and symmetrical figure, please the eye, or a single sweet note pleases the ear, I call this a sense of beauty,” Darwin wrote to Morley. “If the blue and yellow plumage of a Macaw pleases the eye of this bird, I should say that it had a sense of beauty, although its taste was bad according to our standard.”

The principle of sexual selection led to what Darwin called a “remarkable conclusion”: animals can direct evolutionary change. Animal and human qualities, from courage to colorful ornamentation to a capacity for music, had originated in “the exertion of choice, the influence of love and jealousy, and the appreciation of the beautiful in sound, colour or form.” Darwin ascribed to animals something like culture, and to animal culture, a transformative power.

Advertisement

Few today would associate The Descent of Man with communism, but it remains politically fraught for other reasons. Arguing that human beings descend from earlier forms of life, Darwin invokes characteristics he ascribes to “the so-called races” of humans, which differ from one another, he says, in innumerable ways, including appearance, constitution, lung and skull capacity, convolutions of the brain, temperament, and “intellectual faculties.” A vehement abolitionist, Darwin described the “revolting” and “heart-sickening atrocities” of slavery seen on his travels as making his “blood boil” and his “heart tremble.” In Descent he presents an extended scientific argument against the idea of human races as distinct natural kinds, and for the fundamental sameness of all humans.

Nevertheless, Darwin also uses phrases such as “the lowest savages” and “the higher races.” He refers to John Edmonstone, a taxidermist from Guyana who taught him during his time at the University of Edinburgh, as “a full-blooded negro with whom I happened once to be intimate.” Observing that “civilised nations” always tend to overwhelm “barbarians,” he calmly predicts that the “civilised races of man will almost certainly exterminate, and replace, the savage races throughout the world.” Also, while acknowledging that some writers doubt there is any inherent difference between the mental powers of men and women, Darwin writes that men seem plainly smarter, surpassing women in every discipline.

How should we read these passages today? This question recurs throughout A Most Interesting Problem: What Darwin’s “Descent of Man” Got Right and Wrong About Human Evolution, edited by the paleoanthropologist Jeremy DeSilva. Together with ten colleagues, DeSilva courageously takes up this perennially red-hot founding text of his discipline. Agustín Fuentes, an anthropologist, contributes the chapter on race, affirming that “yes, Darwin was racist” but also “a good scientist.” The good scientist prevailed over the racist sufficiently, Fuentes writes, for Darwin to get certain important things right (for example, that humans are the product of evolution and that all humans are fundamentally the same), providing hope for the future of evolutionary theory.

To say that Darwin was “racist” but also “a good scientist” designates a combination of evil and good in his work but doesn’t illuminate it. “Racist” and “scientist” are words alien to the mid-nineteenth century; they aren’t false in application to Darwin, but they aren’t quite right either. “Scientist” came into general usage around the turn of the twentieth century and refers to specialized professionals of a kind that didn’t exist in Darwin’s world. “Racist” entered common parlance in the 1960s and reflects a transformation in which Darwin’s combination of attitudes became unthinkable.

Fuentes’s picture of Darwin the good scientist battling Darwin the racist is attractive: it suggests we can perform the task implicit in the subtitle of A Most Interesting Problem, sorting right from wrong, truth from prejudice, distilling out the pure science. But science is interpretation all the way through, good science and bad science alike; purity is not in the offing and doesn’t make sense even as an ideal. We need another source of hope for the enduring value of scientific theories in general and Darwinian evolution in particular.

I think Darwin’s idea of animal aesthetics suggests one. Darwin assumed an irreducible, mutual interconnectedness between nature and culture—that is, between the phenomena of the physical world and the beauty and meaning that living beings purposefully create. Accordingly, he treated science as one mode of cultural interpretation among others: a powerful, important one, to be sure, but not a pure one. Rather than aiming for purity, science can aspire to self-awareness and engagement in a larger project of understanding.

In support of his view that modern humans form one species, Darwin advances several sorts of evidence. He notes that whenever members of different races have a chance to intermingle and blend, they generate every possible hybrid. Far from producing weak or infertile offspring, these crossings appear salutary, rescuing the “aboriginal race” from the “evil consequences” of contact with Europeans, such as diseases and infertility. He cites the thriving offspring of Tahitians and Britons in the South Pacific. He also insists that the distinguishing traits of all races are highly variable, with no consistently distinctive character, and that the races “graduate into each other.”

Even between those races he takes to be most different, Darwin notes a close resemblance. While sailing on the Beagle, he came to know three people who had been abducted from Tierra del Fuego and brought to England by Captain Robert FitzRoy on an earlier voyage; the Beagle was bringing them home. “I was incessantly struck,” Darwin writes, “with the many little traits of character, shewing how similar their minds were to ours.” Similarly, he invokes Edmonstone, his Guyanese teacher, to illustrate the sameness of minds across races.

Advertisement

Darwin’s principle of human sameness had a taxonomic dimension. As we’ve seen, he maintained that all human races belonged to the same species. He also judged humans to be a mere subfamily of “anthropomorphous apes”—a subfamily currently containing only one species. As the paleoanthropologist John Hawks recounts in A Most Interesting Problem, most of Darwin’s contemporaries considered humans to form an order or family, but Darwin disagreed, citing the similarities between humans and other animals, particularly apes. Nevertheless, biologists continued to consider humans a family-level category until quite recently, when they demoted humans to the level of a tribe, Hominini, within a subfamily that includes gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos. The science journalist Ann Gibbons reports that the human tribe currently includes over twenty known species. Several coexisted with Homo sapiens; at least two, Neanderthals and Denisovans, interbred with them.

This taxonomic revision might sound esoteric, but it’s important: Hawks explains that earlier categorizations implied differences among races of Homo sapiens equivalent to those among other groups of primates. As Darwin understood, the lower we rank ourselves, the closer we place ourselves not only to other primates, but to one another.

Over dinner recently, I mentioned Darwin’s empirical argument in support of the superiority of the male intellect. My son, a college junior, gave an incredulous guffaw and remarked, “I guess Darwin was a lot smarter about the Galapágos Islands than he was about Victorian Britain.” His incredulity reflects a cultural transformation, not a triumph of “good science” over sexism. If we reject Darwin’s notion that men are smarter than women, it’s not because our enlightened science transcends cultural prejudice whereas his benighted science succumbed to it. Rather, a cultural change of many dimensions has strengthened the principle of sexual equality. The zoologist Michael J. Ryan reports in A Most Interesting Problem that biologists today widely accept the theory of sexual selection but, unlike Darwin, who thought males mostly did the choosing in humans, they regard human mate-choice as mutual. I can believe that’s good science, but not because it’s free of cultural influence.

There was an advantage in Darwin’s not having been a “scientist.” The word can lend a counterfeit power to the bearer, implying a special capacity for uttering pristine truths. Darwin, working on the eve of the “scientist” era, generally didn’t claim such powers. As the historian Janet Browne notes in her introduction to A Most Interesting Problem, rather than set science apart from daily life, Darwin seated the reader at his fireside, invoking homely evidence such as his dogs and cats stirring and muttering in their sleep, which, he claimed, revealed imaginative inner lives. Darwin approached his science as a project of interpretive understanding in engagement with many others, citing a philologist’s discussion of the relations between language and thought, a poet’s characterization of dreams, a historian’s account of the development of European morals, John Stuart Mill on social feelings.

Regarding human racial differences, Darwin offered an essentially cultural explanation. Their very superficiality, he argued, rendered them inert with regard to his main evolutionary force, natural selection, which could only promote features beneficial to an organism in the struggle for survival. Racial differences conferred no such advantages, Darwin thought, so they must result mostly from sexual selection: “The continued preference by the men of each race for the more attractive women, according to their standard of taste.”

Darwin’s theory of sexual selection incorporated his Victorian ideas about sex, as several of the authors in A Most Interesting Problem emphasize. But sexual selection also represented his rejection of the reductive notion, dominant then and now, that nature obeys a single principle of optimal design. The ancient idea that nature reflected a divine plan took on new life when many writers interpreted Darwin’s theory of natural selection to mean that each and every feature of a living being had an adaptive purpose. For a century and a half, social Darwinists, eugenicists, and many mainstream evolutionary biologists have cherished this idea of optimal design through natural selection, which is prominent in A Most Interesting Problem.

For instance, the anthropologist Holly Dunsworth rejects sexual selection as a cause of differences such as skin pigmentation or body hair, writing that these are the results of natural selection alone, and that sexual selection has been a sell-out of science to culture and commerce: “Sex stories sell.” Perhaps, but the same goes for the just-so stories that assign an adaptive function to every feature or characteristic: witness 150 years of adaptationist best sellers from Herbert Spencer to Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, and Steven Pinker. Darwin, in contrast, saw living beings as shaping themselves and one another according to their own diverse ideas and tastes.

Unlike Darwin, the scientist-authors of A Most Interesting Problem generally reduce culture to nature. The neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel writes that of all animals, humans have the most cortical neurons, associated with greater intelligence, slower maturation, and longer life. The result, she writes, has been culture: “Biology changes, and culture benefits.” Might cortical neurons also result from culture as well as the reverse? Darwin proposed something like this for upright posture and manual tool use: that each was “partly the cause and partly the result” of the other. But the physical anthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie reports that fossil evidence suggests that erect walking preceded tool use by millions of years, concluding that the adaptive reason for bipedalism remains a mystery. Mightn’t there still be a tangle of mutual reasons, as Darwin suggested, perhaps including the first bipeds’ preferences and personalities?

According to the evolutionary anthropologist Brian Hare, whose “survival of the friendliest” theory says we’re the most sociable hominin, personality is crucial to Homo sapiens’s success. Yet Hare too reduces culture to nature: a “purposeless mechanism,” natural selection, created friendliness, for instance by selecting for the friendliness-inducing hormone oxytocin. Hare invokes Darwin as the originator of the view that morality emerged from a “purposeless process.” Darwin himself said the opposite. He replaced divine purpose not just with natural selection but with mortal purposes. In Descent, Darwin attributes the cultural forms and beautiful features in nature, such as the courtship dance and plumage of the Argus pheasant, to the aesthetic preferences of animals. That such marvels are “purposeless,” Darwin writes, is “a conclusion which I for one will never admit.”

For Darwin, the purposeful activity of living beings shaped the natural world. This originally Romantic vision emerged around the turn of the nineteenth century and receded around the turn of the twentieth. But if you want to see how it looked, you can peruse The Origins of the World: The Invention of Nature in the 19th Century, the sumptuous catalog of an exhibition that ran from May to July at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, behind schedule and truncated due to the pandemic, and further curtailed when its next scheduled appearance, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, was alas canceled.

Last spring, before it opened, I visited “The Origins of the World.” The paintings were hidden behind drapes in the ghostly hush of vacant galleries, the stacks of catalogs covered in dust cloths. I was a guest of the exhibition’s chief curator, Laura Bossi, and one of its scientific advisers, Pietro Corsi. In my experience, viewing paintings in the Musée d’Orsay has involved dancing around in a throng to catch brief glimpses past shifting heads. I could hardly believe my luck at having the place to myself, but felt a chill of dismay at what Covid-19 had wrought. That, too, was consistent with Darwin’s view of the world: full of meaning but also of misery, as Darwin observed in a letter to the American botanist Asa Gray, too much so to be consistent with “a beneficent & omnipotent God.”

“The Origins of the World” displayed the artistic visions of nature to which Darwin both responded and contributed. What did Darwin-era nature look like? In Abelard und Heloise (circa 1900–1915), by the Czech-Austrian painter Gabriel von Max, two capuchin monkeys hold each other in a tender embrace, wearing expressions of wistful resolution (see illustration at beginning of article). Von Max was greatly interested in evolution, read Darwin’s works, befriended the German Darwinist Ernst Haeckel, and kept a family of capuchins at his home. Several of his paintings appeared in “The Origins of the World,” including Pithecanthropus alalus (1894), whose title is a term coined by Haeckel to designate a hypothetical kind of ancient human. The painting shows a stocky, hairy, leathery-skinned, but otherwise human-looking family; a nursing mother gazes intently at the viewer, the father standing protectively at her side.

Primates weren’t the only creatures displaying meaningfulness and emotion in “The Origins of the World.” In Briton Rivière’s Beyond Man’s Footsteps (circa 1894), a solitary polar bear stands on an icy promontory contemplating the sunset. Rivière, a British painter specializing in animals, worked with Darwin on his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), supplying drawings of dogs. “The hostile dog does excellently,” Darwin wrote to Rivière at one point, though he added that the hairs on its neck and shoulders were insufficiently erect. Another drawing, meant to show joyful affection, missed the mark: “I showed it to several of my sons and other members of my family, without any explanation, and they all thought, as I had done, that the expression was that of a humble dog coming to be beaten.” Enclosing a new sketch, Rivière responded that he had been following Darwin’s written remarks in putting the head down rather than up, whereas a dog only wore the expression Darwin wanted while looking a human in the eye, “& so always puts its own head up.” The collaboration is striking for the shared assumption of an absolute union between artistic and scientific scrutiny.

The exhibition’s title is a winking reference to the Musée d’Orsay’s most scandalous work, an 1866 painting by Gustave Courbet entitled L’Origine du monde.2 First owned and likely commissioned by the Ottoman diplomat Khalil Bey, later in the private collection of Jacques Lacan, the painting was much discussed but little seen before entering the museum’s collection in 1995. It presents a startlingly intimate view of the origin of the world for each of us, the passage through which we first enter it. The model was apparently Constance Quéniaux, a ballet dancer at the Paris Opera and Khalil Bey’s lover. The French literary scholar Claude Schopp recently identified Quéniaux from a letter written by Alexandre Dumas fils to George Sand, complaining about Courbet’s painting: “One does not paint the most delicate and the most sonorous interior of Miss Queniault [sic] of the Opera.” The painting and its title assert that an erotic origin for the world is neither less mysterious nor less meaningful than a divine one.

In addition to erotic cosmogony and animal intentionality, the exhibition presented many views of nature’s “art forms,” as Haeckel called them. These included Haeckel’s own renditions of exquisitely intricate, brilliantly colored radiolarians and medusas; Charles-Alexandre Lesueur’s delicate jellyfish trailing elegant, blue tendrils; and many depictions of peacocks and their feathers, which Darwin said had “been rendered beautiful for beauty’s sake,” since they owed their loveliness to sexual selection. This, as Bossi observes in the catalog, is “not only a scientific theory, but also a theory of art.”

A wild and immanent artfulness, and the mortal making of meaning, were on display in “The Origins of the World,” as well as a way of contemplating the world that was at once scientific, artistic, philosophical, literary, factual, sensual, and emotional. Darwin was a virtuoso of this integral mode of contemplation, but he didn’t invent it. He had a model in the German Romantic explorer, naturalist, and writer Alexander von Humboldt, whose writings Darwin carried with him, read to his friends, and tried to imitate. Eduard Ender’s Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland in the Jungle (circa 1850) shows Humboldt sitting in a hut in the Amazon, his traveling companion Bonpland, a French explorer and botanist, standing next to him, surrounded by instruments and specimens; through the doorway we glimpse palm trees, a meadow, distant mountains. Humboldt glances up from some papers while Bonpland holds two magnifying lenses. They look hot and tired, intensely engaged—the image of Romantic immersion.

In effusive letters to his brother Wilhelm, Humboldt described the Amazon: “How brilliant the plumage of the birds and the colours of the fishes!—even the crabs are sky-blue and gold!” (Apparently Humboldt shared a macaw’s questionable sartorial taste.) “Hitherto,” he continues,

we have been running about like a couple of fools; for the first three days we could settle to nothing, as we were always leaving one object to lay hold of another. Bonpland declares he should lose his senses if this state of ecstasy were to continue.

In the catalog, the historian of science Marie-Noëlle Bourguet emphasizes the oneness of emotional, artistic, literary, and scientific responses in Humboldt’s writing, quoting his Essays on the Geography of Plants, where he describes the sight of Central and South American vegetation as “thrilling,” “overpowering,” “magnificent,” and “exhilarating.”

Literary language was essential to Humboldt’s science; he also urged the importance of art, proposing an anthology of landscape paintings and exhorting young artists to travel. The American painter Frederic Edwin Church took this advice, following Humboldt’s route through the Andes. Church’s giant painting of Cotopaxi, an erupting volcano, was included in “The Origins of the World.” The volcano spews an ugly cloud of smoke across a delicate blue sky, while the rising sun struggles to shine through; contemporary American viewers saw the painting as an allegory of the Civil War, understanding it as at once artistic, scientific, historical, and political.

This way of understanding had a beginning and an end, as the exhibition made plain. The opening paintings showed what came before: the cultivated, domesticated, divinely allegorical Nature of the Renaissance earthly paradise. The closing paintings displayed what came after: the symbolism and abstraction of the early twentieth century, with artists abandoning the integral vision of the earlier period.

Speaking of blue and yellow, a splendid macaw of those controversial colors graces the cover of the new edition of The Natural History of Edward Lear, edited by the naturalist and curator Robert McCracken Peck.3 As Peck explains, Lear would likely find his present-day fame—attaching mostly to his nonsense verse, his owls and pussycats—a bittersweet surprise. An exact contemporary of Darwin, Lear saw himself primarily as a natural history and landscape painter with an expertise in ornithology. Peck writes that Lear was “besotted” with parrots, his “favourites.” His Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots (1830–1832) was the first English natural history book to focus on a single family of birds and made him one of the leading ornithological illustrators in England.

Lear preferred to draw from living birds, then a rare practice, writing that he was “never pleased with a drawing unless I make it from life.” He sketched not only at the London Zoo but at the Zoological Society’s headquarters on Bruton Street, which housed many live animals. Coming and going as he liked, he was even allowed to take birds from their cages. Accordingly, Lear’s birds look alive, as Peck points out: they’re dynamic, emphasizing motion and flight, and full of personality, “perky and slightly impish.” It wasn’t just birds: “I do not feel competent to undertake quadrupeds,” Lear wrote, “unless I draw them from life.”

According to Peck, Lear “saw very little distinction between human beings and other living creatures. Whenever he found a line between them, he worked hard to blur it.” Sympathy inspired Lear’s interest in the vital agency of animals. Rather than anthropomorphism, he went for “zoomorphism” in his cartoons and verses, assimilating human characters to animals; his limericks transformed humans into birds, snakes, frogs. While he versified the animal aspects of humans, he also humanized animals. When he made portraits of the first live chimpanzee to be kept at the London Zoo, who arrived from Gambia in October 1835, Lear showed the animal a particular respect. The zookeepers had named him “Tommy” and dressed him in children’s clothing. Lear did the chimpanzee the honor of referring to him by his scientific name. In the portraits, as with von Max’s capuchins, the chimpanzee’s expressions and poses reveal a distinct personhood.

One of Lear’s inventions was the Scroobious Pip, a creature that defies taxonomy, appearing to be neither fish nor insect nor bird nor beast. The other animals try to figure it out but ultimately give up and ask it what it is. Its answer is unsatisfying—“My only name is the Scroobious Pip”—so they keep on asking, and it patiently repeats itself, until at last they concede: “Its only name is the Scroobious Pip.”

Lear never quite finished “The Scroobious Pip,” but he started it in 1871, which brings me back to where I began. When Darwin wrote The Descent of Man 150 years ago, the idea that humans were the products of evolution sounded to many like communism. A belief in fundamental human sameness was compatible with a belief that some races were smarter than others and men smarter than women. These juxtapositions now seem illogical, indefensible, unthinkable. Which of our own assumptions will be unthinkable in a century and a half? We can’t know, but at least we can know that we can’t know.

The best of Darwin’s science comes from his awareness that he’s making sense of an irreducible, living, self-forming world from within, not from on high, and from his impulse to draw upon every form of understanding available. The worst comes from his loss of this awareness and this impulse, when he atomizes humans into rankable traits. Encountering a Scroobious Pip, we can study it, draw it, question it, describe it in prose and verse. In working to comprehend it, we should bring everything we have to bear; its essence, in the end, is its own.

This Issue

October 21, 2021

The Storyteller

‘Who Designs Your Race?’

Are the Kids All Right?

-

1

The Communards also conducted summary executions of political prisoners, but Versailles outdid them by at least a couple orders of magnitude. See John Merriman, Massacre: The Life and Death of the Paris Commune (Basic Books, 2014), chapter 11. ↩

-

2

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts exhibition was to have been renamed, with classic Canadian modesty, simply “The Origins.” ↩

-

3

First published by Godine in 2016. ↩