In our all-or-nothing culture, creative work is too often either apotheosized or ignored. You’re a rock star or you’re nothing. The public has little appetite for nuance. This makes it difficult to write about the achievement of Joan Mitchell, who was born in 1925, grew up in an affluent and literary Chicago household, and was a presence in artistic circles in New York and Paris from the 1950s until her death in 1992. Mitchell was a painter of rare lyric intelligence. Like nearly all artists who embrace painterly improvisation as a discipline or maybe even a calling, she produced, along with some formidable works, many more that, at least in my view, rehash and sometimes even parody her major accomplishments. It’s possible to feel that Mitchell’s missteps and muddles—and there are a lot of them—make her successes all the more exhilarating. But by the time I came to the end of the large retrospective of her work currently at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, I was afraid that a triumphalist chill had settled over this fascinating figure and the inebriated poetry of her finest canvases. The hell-raising rhetoric of Mitchell’s abstractions—the best tend to come from close to the beginning and near the end of her career—had been stifled by a ponderous, dutiful presentation.

For all I know, Sarah Roberts and Katy Siegel, the curators in charge of the retrospective, have their own reservations about this hulking account of a complex career. (It was co-organized with the Baltimore Museum of Art, where it will travel next year.) Roberts and Siegel haven’t allowed Mitchell’s renegade energies to be entirely defeated by the boxy, generic SFMOMA galleries. While large canvases—such as the roughly twenty-two-foot-wide La Vie en rose (1979)—dominate the show, the curators have included works on a more intimate scale that reveal Mitchell’s questing, probing spirit. Her close connections with communities of poets on both sides of the Atlantic are highlighted in a display case containing a selection of the books she owned. The audio tour features commentary by the painter Stanley Whitney and the poet Eileen Myles, creative spirits whose stalwart independence parallels Mitchell’s own. And a standout in the immense catalog—there are twenty-one contributors—is a memoir by the French composer Gisèle Barreau, a close friend, who discusses Mitchell’s wide-ranging musical enthusiasms, with a particular focus on vocal traditions ranging from bel canto opera to the jazz singing of Billie Holiday and Nina Simone.

But whatever the organizers have done to affirm Mitchell’s individualism and reclaim the difficult, idiosyncratic painter’s painter she was before her auction prices began to escalate, they are up against inflationary forces that are as much critical as economic. At a time when a curator or critic who makes discriminations can be accused of prejudice, it may be easiest to do away with all the shadings. Why risk saying that something’s good or even not so good when everybody will be happy if you say it’s great? These malign forces, which flatten out whatever is quirky, prickly, and intractable in Mitchell’s work, threaten to distort our understanding of nearly every figure in the modern expressionist tradition of which she is a part.

A case in point is Cy Twombly, a close contemporary of Mitchell’s. Nowadays you’re unlikely to hear any criticism of Twombly, who began in the 1950s by creating ravishingly elegant painterly graffiti but in his later years produced little aside from bloated scribbles. The galleries and museums that present his most vacuous compositions as if they were masterworks figure that nobody’s going to make any trouble when the paintings are selling for millions and everybody knows that taste is in the eye of the beholder. I also worry about a tendency in recent years to regard other contemporaries of Mitchell’s—Lee Krasner and Milton Resnick come to mind—as heroic American originals rather than highly intelligent and accomplished practitioners of a New York School style who had long ago been recognized by their own community. “Great” becomes meaningless when nothing can be merely good.

This collapse of judgment has spread far and wide. We no longer even question the stratospheric evaluations of the paintings of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and the other artists who meant so much to Mitchell when she first arrived in New York. Their early admirers and advocates could see weaknesses and outright failures in their work that have been lost in the hagiographies produced over the decades. If nobody can hazard an honest assessment of Pollock or de Kooning, it becomes exceedingly difficult to write in any measured way about Mitchell, who was building on their achievements. I believe that some of her finest paintings—from Evenings on 73rd Street (1957) to River (1989)—bear comparison with the high points of de Kooning’s career, from Attic (1949) to Door to the River (1960). But I would also argue that the bombast that all too often infects Mitchell’s work is no worse than—and indeed has parallels with—the empty virtuosity that was eventually de Kooning’s undoing. In the mid-twentieth century, when Abstract Expressionism was first taking the world by storm, Randall Jarrell worried about living in an age when criticism sometimes threatened to eclipse the creative act. What he failed to account for was the extent to which the creative act has always depended on the presence of a vigorous critical tradition.

Advertisement

Joan Mitchell was a Romantic. Like the painters and poets who first defined the Romantic spirit in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, she was a connoisseur of subjectivities. Nature and culture engaged her because they mirrored or illuminated her own feelings. To look outside was to look inside. The color of a flower, the contours of a landscape, the rhythms of city life were empirical phenomena but also mental impressions that generated pictorial images. Her mother, Marion Strobel, was a poet who for a time was associate editor of the magazine Poetry, and from very early on Mitchell saw a profound connection between the way poets distilled experiences into words and painters distilled them into images. Her friendships with writers, among them John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler, and Jacques Dupin—all, in their different ways, Romantic figures—reaffirmed a belief, which Baudelaire had shared with Delacroix, that reality isn’t so much a model to be slavishly copied as a vocabulary to be reshaped however the artist or writer chooses.

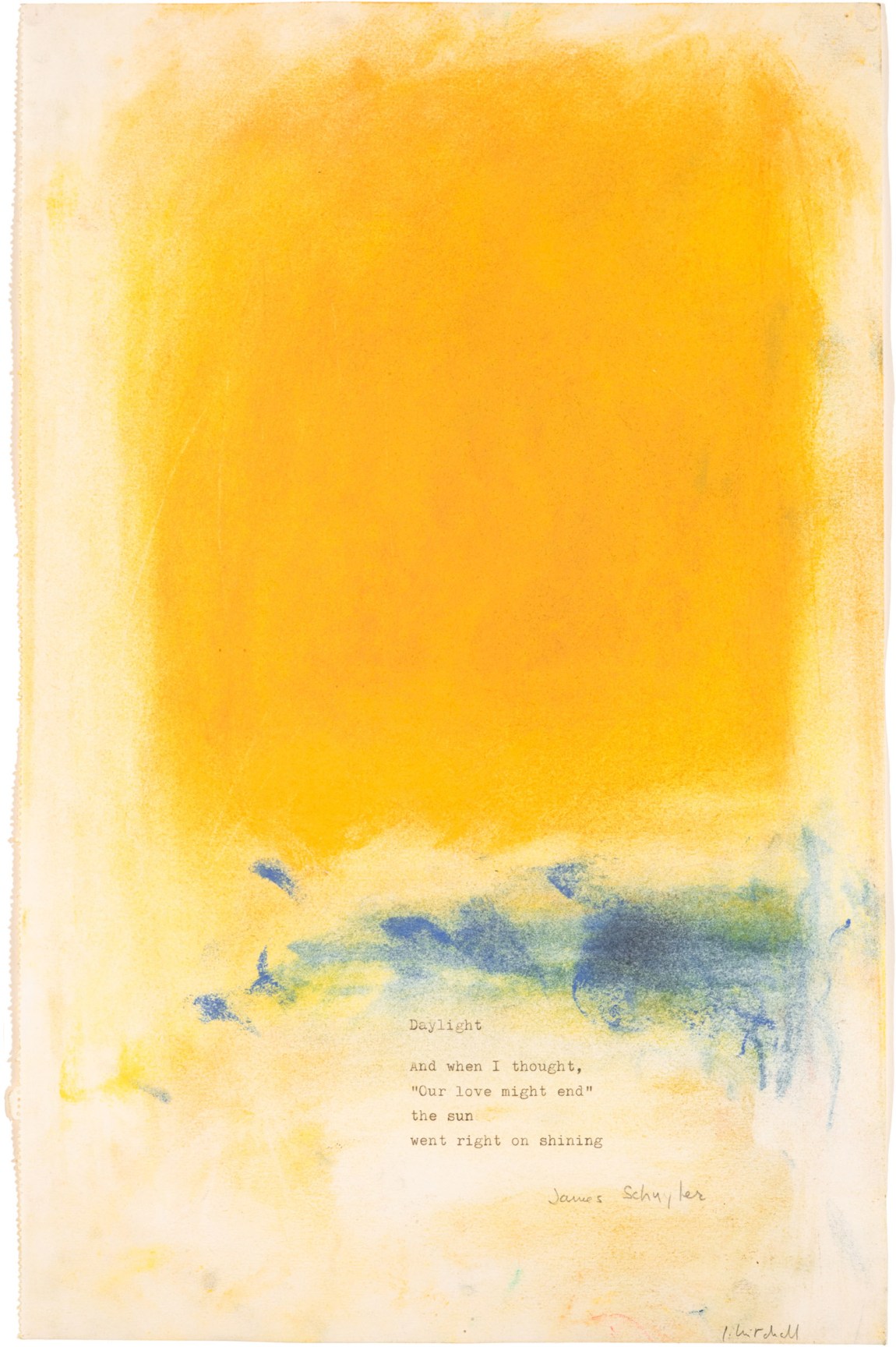

Among the most revealing works in the Mitchell retrospective are three modest compositions on paper from around 1975, each little more than a foot high. A brief poem by Schuyler has been typed on each sheet, and around them Mitchell has worked expanses and scrawls of pastel that echo or adumbrate the images in the poems. The correspondences between words and images that she explores can seem simple, but this elementalism is key to the pungency of her finest work. For “Daylight,” a poem in which the fear that a love affair might end doesn’t stop the sun from shining, Mitchell floods the paper with a fierce yellow that’s disturbed only by a few scribbles of melancholic blue (see illustration on the right). For Schuyler’s “Sunday,” in which a lover may be glancingly evoked through a “mint bed…in bloom,” a “lavender haze/day,” and green grass creating “cutting lights,” Mitchell contrasts a vaporous pale purple with the sharpness of green and black pastel strokes. Her handling of the pastel, with striking juxtapositions of larger, softly worked areas and passages of sharp, blunt calligraphy, transforms Schuyler’s nature poetry, which doubles as love poetry, into an abstract drama of psychological and emotional crystallizations. Mitchell’s entire achievement is grounded in this kind of intuitive, impressionistic process.

Back in 1965, after observing that “the relation of [Mitchell’s] painting and that of other Abstract Expressionists to nature has never really been clarified,” Ashbery came as close to defining that ambiguous relationship as anybody ever has. What he described was a mutable and perhaps ambivalent connection:

One’s feelings about nature are at different removes from it. There will be elements of things seen even in the most abstracted impression; otherwise the feeling is likely to disappear and leave an object in its place. At other times feelings remain close to the subject, which is nothing against them; in fact, feelings that leave the subject intact may be freer to develop, in and around the theme and independent of it as well.

With Mitchell we are in a realm of abstract painting that has nothing to do with the ideal order sought by Mondrian, Malevich, and some of the other pioneers of nonobjective art. If Mitchell seeks an order in abstraction, it’s a Romantic order, pastoral in spirit. The world around her inspires moods and yearnings, joy and melancholy. Even the evocations of city life in some of her earliest triumphs, especially Evenings on 73rd Street, suggest a Romantic view of the metropolis, with the urban maelstrom and its competing pressures mirroring the individual mind, much as they do in the poetry of Walt Whitman and Hart Crane.

I think it’s only in the work of the last decade or so of her life that Mitchell was able to fully embrace the richly layered view of nature that Ashbery described back in 1965. Beginning in 1982 with the green and orange-gold ecstasies of a series of small paintings titled Merrily and Petit Matin and climaxing with large canvases including River, South (both 1989), Sunflowers (1990–1991), and Untitled (1992), she unites color and line to create some of the most deeply affecting calligraphic convulsions in the entire expressionist tradition. River (unfortunately not included in the exhibition), with its horizontal bands of meandering, curving and curling paint strokes, comes as close as Mitchell ever would to evoking the actuality of her home in Vétheuil, not far from Paris, where her windows framed a spectacular view of the meandering Seine. In Untitled (perhaps her final painting) the gatherings of yellow strokes almost suggest sunflowers, while the painting from a year or so earlier that is actually titled Sunflowers fends off and complicates the association with gatherings of dark blues (see illustration on page 8). Everywhere in these later works nature’s facts and Mitchell’s feelings are joined—almost married—in paint. This union of outer and inner worlds yields something new in the visual arts: an operatic lyricism.

Advertisement

Mitchell’s rapturous color, both in oil paintings and in works on paper, is her most significant contribution to Abstract Expressionism, that quintessentially American art movement. Some may see a paradox here, because to the extent that Mitchell did reformulate Abstract Expressionism, she did it while living in France, where with the passing decades her color became stronger and clearer. In one of a group of filmed interviews with this highly articulate artist that are presented in a gallery at SFMOMA, Mitchell observed that there were very few colorists working in New York. Whatever specifically she had in mind in the work of her contemporaries, it’s certainly true that color is rarely the strongest element in the paintings of Pollock, de Kooning, Franz Kline, or Philip Guston. Much of their work tends toward the monochromatic, and even when de Kooning introduces a great many colors, what he produces is a general chromatic atmosphere, with little or no emphasis on the impact of specific juxtapositions of color. That’s rarely the case with Mitchell, who even in her less authoritative works is focused on the force of particular colors and the dissonances and radiances that a few carefully chosen primaries and secondaries can create as they interact. Consider South, in which the genially intermingled blues, yellows, and greens are set in a startling counterpoint with a cascade of sharply angled deep red strokes.

Although some of the artists of the past whom Mitchell admired the most, especially Cézanne and Van Gogh, had been revered in New York’s downtown artistic circles long before she arrived, I cannot think of an American painter who studied Van Gogh’s thunderous orchestrations of primary and secondary colors more closely than Mitchell. She saw how Van Gogh marshaled his thickly applied pigments to create rhythms, syncopations, and even a sense of ascending and descending chromatic scales. She learned, probably from Van Gogh, how to flood the canvas with a single color and then to redouble its impact with dramatic, conflicting accents in some complementary one. She also understood how the way that a pigment is applied can alter its effect. She was particularly impressed, during a visit to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, by a late canvas by Cézanne, Morning in Provence, in which a seemingly harmonious commingling of blues and greens is made dramatic through the relative densities and transparencies of the individual paint strokes. With Mitchell, colors are always in conversation.

If there is a figure among the Abstract Expressionists whose feeling for color seems related to Mitchell’s own, it’s Hans Hofmann. Hofmann, who was born in Germany in 1880, had spent decades absorbing the European coloristic traditions by the time he settled in the United States in the 1930s. But at least in recent years there has been a certain hesitancy about suggesting any strong association between Mitchell and Hofmann, who ran a famous art school in New York and Provincetown for a quarter-century. That’s because Mitchell once remarked in an interview that she had attended only one class at the school and fled, recalling of his teaching, with something like dismay, that she had “wondered why and why and why.”

I’m reluctant to take this recollection at face value. Like many people who find themselves confronted by an interviewer’s questions, Mitchell wasn’t averse to shading or twisting the truth. Éric de Chassey, in an essay in the SFMOMA catalog, cites her assertion that “I am not involved at all in the French scene,” a self-evidently absurd pronouncement from an artist who knew many of the central figures in the French literary and artistic world and exhibited in Paris for decades. I’ve always suspected that whatever Mitchell’s appearances at the Hofmann school were like, she took the lessons of this master very seriously. That is confirmed in Since When, the posthumously published memoirs of Bill Berkson, a poet she knew over the years. He recalls that Mitchell, during a public conversation they had in San Francisco, “expound[ed] beautifully on the gists of Hans Hofmann’s classes and their importance for her in the early fifties.”

More than any other artist in New York in the postwar years, Hofmann understood the synesthetic possibilities of color that Van Gogh, Kandinsky, and Matisse had seen as the essence of the modern adventure. For Hofmann colors were raw emotions. He knew how to clarify those emotions through shape, placement, and emphasis. Like Hofmann before her, Mitchell recognized the poignancy of color—and how its absence could be almost heartbreaking. When her color gets murky or muffled, as in some works of the mid-1960s, we register this as a denial, a withdrawal—it hurts. When her color is opulent, we’re exhilarated—blissed out. In her best work, an old-fashioned French hedonism is tempered by her American bullshit detector. There’s a toughness to her sensuousness.

Mitchell’s epochal ambitions were sometimes her worst enemy. There are long stretches in the SFMOMA retrospective, especially in the rooms that feature her triptychs and quadriptychs (even the word is awkward), where she reaches for a monumentality that amounts to a betrayal of her lyric gift. I realize that I may well be in a minority. At a members’ preview that I attended, visitors seemed to savor the gathering complexities of Sans neige (1969), Ode to Joy (A Poem by Frank O’Hara) (1970–1971), Bonjour Julie (1971), La Vie en rose, and Salut Tom (1979). My guess is that what people see in these paintings is abstract storytelling, with the jostling rectangles, rising and falling forms, and thickening and thinning atmospheres composing a fairy tale for adults. I watched as members of San Francisco’s astute museumgoing public parsed these huge paintings, pointing out relationships, parallels, echoes, and evolutions. I don’t deny that what they were seeing is there. But when Mitchell piles up colored rectangles to create a sort of abstract architecture, as she does in many of the larger works of her middle years, the results can feel programmatic. People read the program. In her strongest works, the colored strokes move through a fluid space, defining dimensions and directions without ever locking things down. Her best paintings have a peremptory power—an all-in-one immediacy—that can’t be parsed.

If I’m right in thinking that Mitchell wasn’t always at her best in the 1960s and 1970s, some of the trouble may go beyond the studio to the life she had chosen to live and the art world in which she found herself. She didn’t necessarily have the consistent time in the studio that she probably needed during the years when she was in a stormy relationship with the French-Canadian abstract painter Jean Paul Riopelle, who had a yacht on which they sailed the Mediterranean, living a life of sunstruck bohemian glamour. It’s also important to remember that Mitchell, along with many other artists of her generation, was unprepared for—even bewildered and repelled by—the art world’s embrace of Pop, Op, and Minimalism.

For painters who had fallen in love with the work of the American Abstract Expressionists when they were first achieving international prominence, Pop Art, with its swaggering ironies, could be felt to pose a threat to everything they held dear. But however thoroughly Mitchell rejected the new smorgasbord of styles, I wonder if she didn’t, perhaps unconsciously, see in her bigger and louder new works some way of responding to Andy Warhol’s world. Sans neige is one of a group of paintings from the 1960s in which her color is unpleasantly—and uncharacteristically—strident. I suspect that she was trying to compete with the artificial color that dominated art, fashion, and advertising in those years. Whatever the explanation, through much of the 1960s and 1970s she strikes me as an artist at war with her gifts.

Mitchell must have been aware, in her later years, that some artists, critics, and museumgoers were taking a renewed interest in the midcentury New York avant-garde of which she was such an important part. A retrospective of her work that toured the United States in 1988–1989, much like the retrospective of Fairfield Porter’s paintings at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts five years earlier, signaled a heightened focus on formidable talents who in the Warhol years had too often been sidelined as painter’s painters, of interest only to a specialized audience. This is not to say that Mitchell had ever really been overlooked. While there may have been times in those middle years when her work was better known in France than in the United States, she always had gallery shows in New York and she had already been the subject of an exhibition at the Whitney in the 1970s. But the shows of her recent paintings mounted in New York in the 1970s and 1980s, first by the Xavier Fourcade Gallery and later by the Robert Miller Gallery, brought a new generation to her work. I suspect that Mitchell was emboldened by the younger artists who embraced her singularity; a few of them became good friends. Years earlier Frank O’Hara had inscribed a copy of his Lunch Poems “for Joan for saving Abstract Expressionism—Love, Frank,” and then crossed out “Abstract Expressionism” and added “everything.” In the 1980s there were those who found themselves thinking along similar lines.

Mitchell’s exhibitions at the Robert Miller Gallery were eloquent, authoritative. Ashbery composed an essay about his old friend for the catalog of a show mounted there shortly after her death. He began by explaining that he had first seen her work when he arrived in New York in the early 1950s. He concluded by discussing a late painting titled Ici (1992):

Ici—Here!, Mitchell seems to be saying at the end of her life, is where life is, is what it is—one of those truths under one’s nose that one ignores for that reason but which, in the right circumstances, can transform itself from truism into palpitating reality.

Can a painting be a “palpitating reality”? That’s the question that Mitchell asked again and again. Looking at her finest compositions we find that we’re alive to a work that is alive to the world. Her brushstrokes are the veins and arteries of her art. Life-giving energies emerge.