In his book Lihiyot Ba’olam (Being-in-the-World, 2014), the Israeli historian Boaz Neumann took on an intellectual challenge. Drawing on primary sources, Neumann—who died of cancer at the age of forty-three a year after the book’s release—provided an intimate portrait of Germans from the turn of the twentieth century through the end of the Weimar Republic. The book assumed the perspective of someone who, like his subjects, was unaware of what was to come, namely the rise of Nazism. Shunning a historiographical approach that sees the Weimar period as little more than a precursor to Hitler, Neumann regarded it—to borrow his terminology, which he borrowed from Heidegger—on its own “time.” He lingered with ordinary Germans—working, eating, falling in love, growing bored—in their own present moments. Quoting extensively from journals marking uneventful days, he found significance in often-overlooked details, such as a waiting room with “chairs that looked as if assembled hastily from other rooms to seat unexpected guests.”

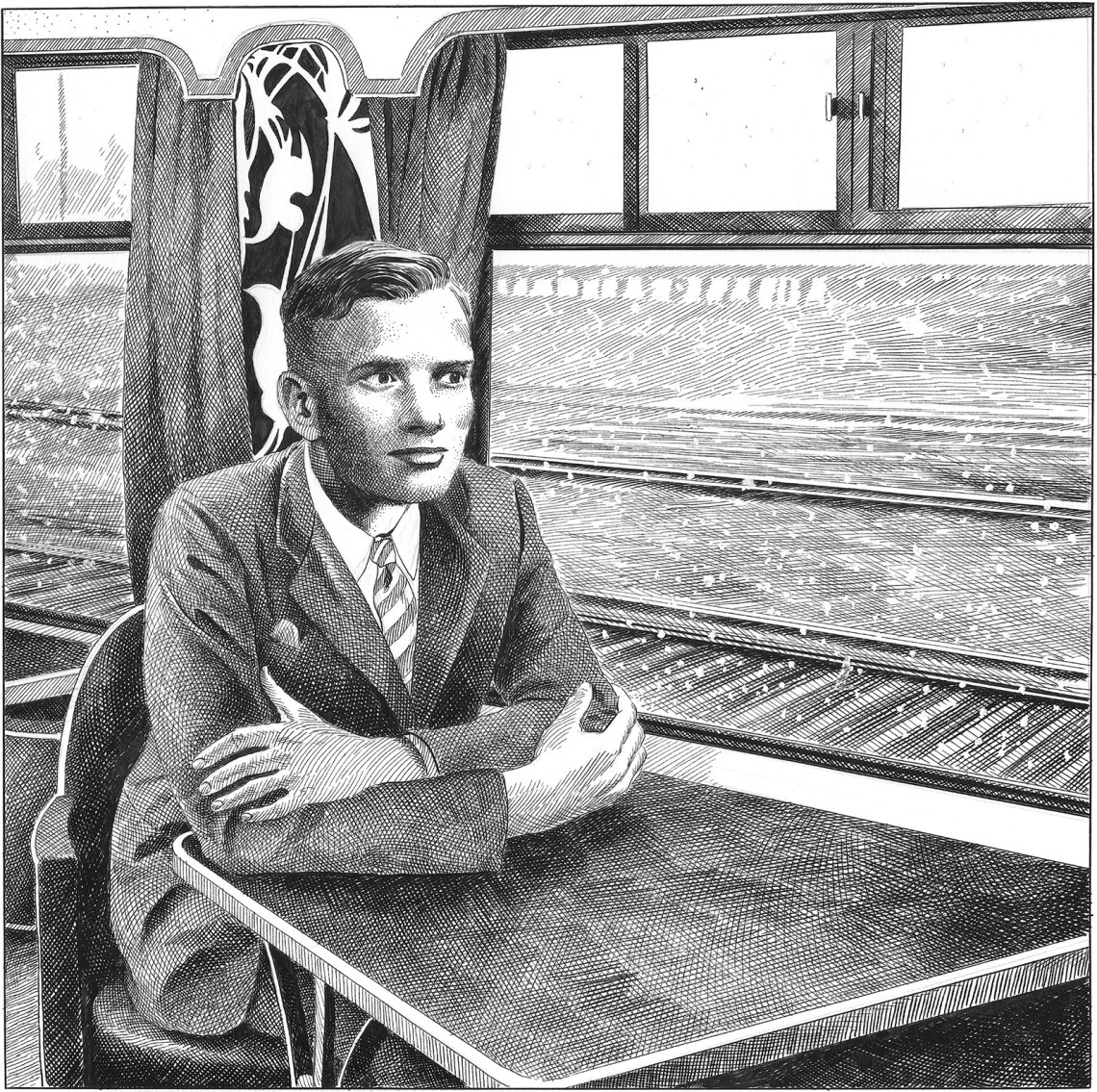

The Passenger, a novel by Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz, is stunning in the way it dwells—another Heideggerian term—on the life of one man just before World War II. Otto Silbermann, a wealthy Jewish Berliner, is locked in the abyss of the days immediately following Kristallnacht in November 1938, when the Nazis broke into Jewish-owned homes, vandalized Jewish businesses, torched synagogues, beat Jews on the street, and shipped off 30,000 Jewish men to concentration camps. There is no artifice to the writing: Boschwitz completed the novel in less than a month that same year, effectively fictionalizing events almost as they were happening, even though he had left Germany three years before.

The circumstances surrounding a novel’s creation may help illuminate it but should not eclipse it. (Things are different in philosophy: that Heidegger became a member of the Nazi Party does—indeed, should—complicate our reading of his work.) In the case of Boschwitz, however, it is hard to keep his novel separate from his biography. His father, who was Jewish, died as a German soldier in World War I, just before Boschwitz was born. His mother raised him as a Protestant. In 1935 the two fled to Sweden after the Nazis imposed the Nuremberg Laws; a year later he moved to Oslo, where he wrote his first novel, Menschen neben dem Leben (People Parallel to Life), which appeared in Swedish translation under the pseudonym John Grane in 1937. After spending time in France, Luxembourg, and Belgium, he rejoined his mother in England in 1939, shortly before the war broke out. There Boschwitz published The Passenger in an English translation titled The Man Who Took Trains, to a scant readership. A year later he was sent to an internment camp in Australia, where he reworked the novel. In 1942 he was allowed to return to England, but a German submarine torpedoed his ship, killing him and 361 other people on board. He was carrying the revised manuscript.

As a result of his untimely death at the age of twenty-seven, Boschwitz’s legacy is woefully slim. The literary world did not recognize how much had been lost until his niece mentioned to the publisher Peter Graf the existence, in a Frankfurt archive, of the original German typescript of The Passenger. Graf read the novel in a single sitting in 2015 and decided to edit it, incorporating notes from Boschwitz’s last letter to his mother about the revisions that he thought would improve the book. In 2018, eighty years after it was written, the novel was finally published in German as Der Reisende. That edition has now appeared in a lucid English translation by Philip Boehm.

The novel is remarkable precisely because of the immediacy of its plot—its sense of being written in a continuous present. Boschwitz, who was twenty-three when he finished it, was able to capture what happens when a regime turns on its own citizens and treats them as pariahs, with savage force and daily degradations dressed up in legalese. He had an ear for dialogue and a penchant for the absurd. Like Gregor Samsa, Silbermann wakes up to a twisted new reality. He may not have turned into a vermin overnight, but he is regarded as if he had. “As of yesterday I’m something different because I am a Jew,” he thinks. He has become “a swear word on two legs.” When he holds out his hand to a man he has long known and the man tells him quietly, “Please don’t,” Silbermann can feel his face flush and is “ashamed of his shame.”

This Issue

November 18, 2021

Bringing the Supply Chain Back Home

The White Heat of Conviction

-

*

Marjorie Ingall wrote about the phenomenon earlier this year in “Why Are There So Many Holocaust Books for Kids?,” The New York Times Book Review, July 8, 2021. ↩