Lisa Yuskavage was twenty-one in the spring of 1984 when her parents drove her up from Philadelphia for her admissions interview at the Yale School of Art. The colorful paintings of people in a swimming pool she had made as an undergraduate at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art were too wide to fit inside their VW bus, so she devised a system of sawing the stretcher bars in half and folding the paintings, which she could put back together with brackets and screws once they arrived in New Haven. The impending interview made her father, a truck driver, nervous. As Lisa began to open her paintings in the subbasement of Yale’s Art and Architecture building, he tried to help her. Dad, stop! Please, just let me do it! Leave me alone! she barked. Then she noticed a tall man across the room watching them and grinning, laughing even. On top of everything else, she’d become someone’s entertainment. I can’t stand that guy, she thought. Thank God I’ll never have to see him again.

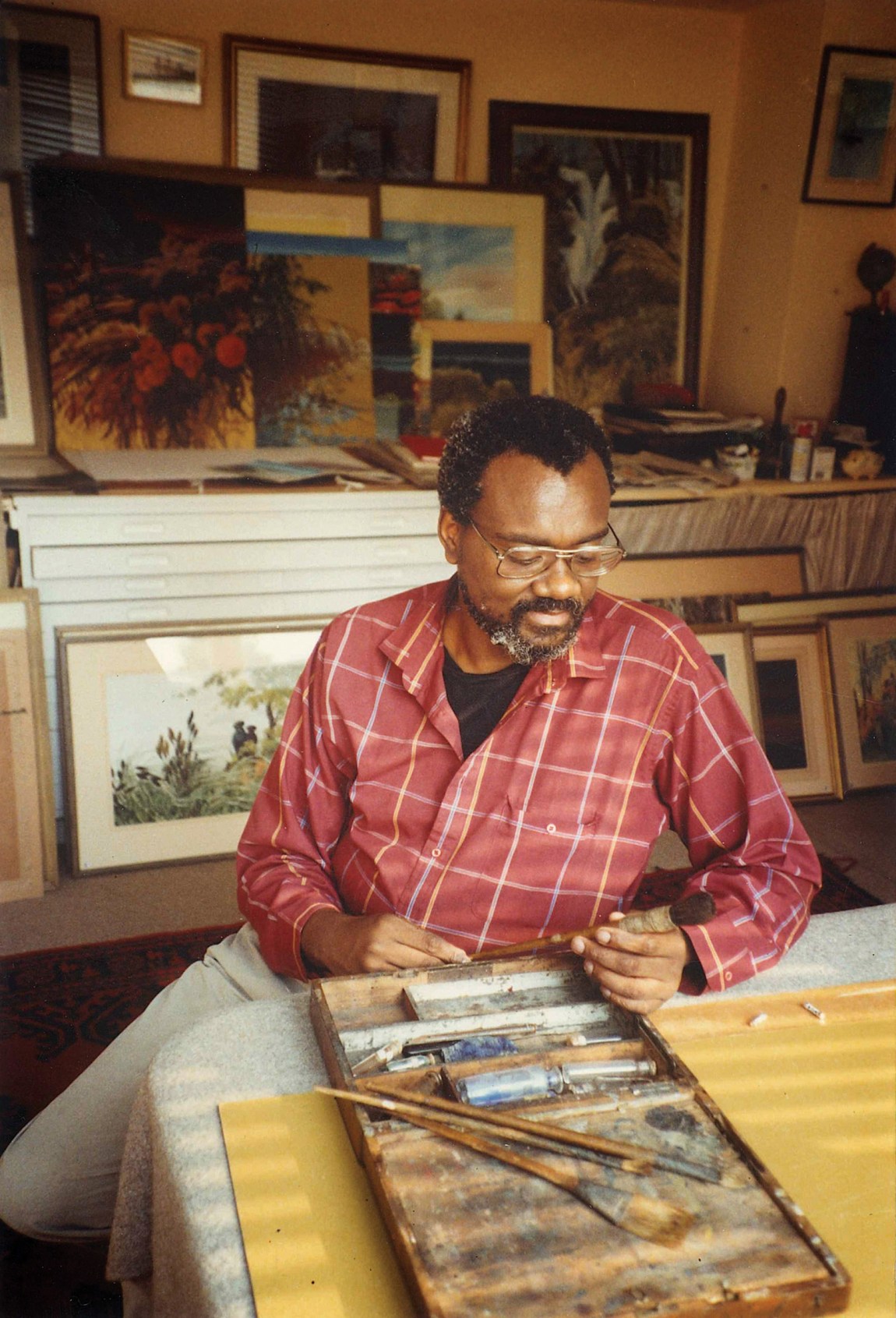

The laughing man was Jesse Murry, whose admissions interview followed hers. At thirty-five, he had just spent two years teaching art history at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in upstate New York and was already well known in the New York art world, having curated an exhibition of the outsider spiritual artist the Reverend Howard Finster at the New Museum and written a number of rigorous essays on contemporary abstraction for Arts Magazine. Although he had been painting since his twenties, he remained frustrated by how far his intellectual understanding of art outpaced his skills as an artist. The works he brought along for his interview were modest abstractions deeply influenced by the American painter Arthur Dove.

Many of those who knew Murry remember his intelligence, his manner of thinking and speaking, as incandescent.1 In the admissions interview the art historian and painter Andrew Forge asked him why he wanted to go to graduate school to become a painter, since he had so clearly established a path for himself as a writer and historian. Channeling the theater critic Addison DeWitt in All About Eve, Murry proclaimed, “I have not come to New Haven to pull the ivy from the walls of Yale!” By then Murry was well accustomed to wielding his southern Blackness and his queerness—his layered difference—alongside his dazzling erudition as a means of disarming the hostility of the world and going where he wanted to go, against all odds.

Yuskavage was accepted to the Yale School of Art, class of 1986. At her orientation in the fall of 1984, she was horrified to see that same grinning man waving enthusiastically at her from across the room. Murry had been accepted as well. Over the first semester they got to know each other in classes, critiques, and studio visits, and began to gravitate toward each other as outsiders at Yale. They both resisted the formalism of New York School painting as well as the emerging irony of postmodernism; they were trying instead to infuse their work with the content of their lives in a shared romanticism about art that their classmates found willfully naive.

Her professors’ relentless criticism of her work took its toll on Yuskavage—the big, psychologically dense pictures she wanted to paint were, they declared, beyond her talents. By the end of her first semester she was making muddy still-lifes, formal exercises, and nothing more. The spark from those early colorful figurative paintings had been lost. The pressure of academic expectations and the stinging divide between her working-class childhood and this bastion of elitism festered into a crippling depression, so she went to Yale’s mental health clinic for emergency counseling. A therapist told her to paint where she was at emotionally.

Yuskavage began making small, nearly monochromatic works of a female figure in bed against a wall with covers pulled up to her head; the blanket stretched out into a field where a dead girl was being buried. When Murry saw these new paintings in her studio, she confided to him that she’d started seeing a therapist. He told her that he was thrilled for her, that going through serious analysis would transform everything she did. He emphasized that examining her depression was not a punishment but a gift, one that could give her a profound self-knowledge necessary for her art.

Murry was speaking from hard-won experience. He had been born in 1948 in Fayetteville, North Carolina, to a musically gifted single mother whose mental health deteriorated throughout his childhood. As a result he was forced to live with relatives—a grandmother in North Carolina and then an aunt in New York, near White Plains. Along the way Murry was abused both sexually and psychologically, and given no consistent sense of security, family, or home. He learned he could disappear into books. Around the age of eleven, he found one on the Venetian Renaissance that changed his life. In a reproduction of Giorgione’s The Tempest a landscape unfurled that he could enter, as he later described, “with all the affective resonance of a dream.”2

Advertisement

He went to the White Plains library every day until he had read everything in the children’s section. Then he asked one of the librarians, an elderly white widow named Isabel Clark, to give him access to more grown-up reading and the special art books locked in glass cases. The two became friends, and soon Clark was made Murry’s legal guardian. Once he graduated from high school, she offered to send him on a trip around the world. As much as he wanted to see the masterpieces he had loved in books, he asked for another gift instead: that she pay for him to undergo intensive psychotherapy. It was a remarkable act of self-preservation.

Murry’s conversation with Yuskavage about psychotherapy proved vital to the two artists’ friendship. He was the first person she had told about her depression, and his response helped her to proceed without shame or guilt, and to understand therapy as essential to progress in her work. Soon she was making paintings with multiple figures not looking at one another, in rooms suffused with gentle light. When Murry saw them, he said they reminded him of paintings called sacred conversations.

Giovanni Bellini’s altarpiece by that name in the church of San Zaccaria in Venice depicts the Madonna holding the Christ Child, both flanked by saints. Each figure is turned inward, not talking but listening, united by the magic of painting, which brings them together through time, space, and most importantly the force of color. Seeing it as an eighteen-year-old while she was studying in Italy was an epiphany for Yuskavage; she thought that the “sacred conversation” was how the figures were communicating psychically and how she was communing with them, with Bellini, and with God, by just looking at it. The altarpiece gave her a sense that she knew what painting was and how to do it, though she could not explain it. Now Murry had glimpsed its echoes in her own modest work.

He then told Yuskavage that sacred conversations made him think of the way his favorite poet, Wallace Stevens, conceived of “mind,” wherein “God and the imagination are one.” He asked if she knew Stevens’s poem “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour.” She didn’t. He insisted that she run to the bookstore to buy a copy of The Palm at the End of the Mind. When she came back, he read the poem aloud:

Light the first light of evening, as in a room

In which we rest and, for small reason, think

The world imagined is the ultimate good….

Within its vital boundary, in the mind.

We say God and the imagination are one…

How high that highest candle lights the dark.

The poem captured what Murry believed art was and what he aspired to achieve in his own painting. Art need not merely represent the external world; it could also reflect the inner world of the mind, where we commune with a higher power. For Murry, this required art to move beyond the historical or geographical boundaries of a singular “self.” It was sacred work that took on the wholeness of human experience, and it was far removed from the modernist dead ends they’d been offered at art school.

In his first year at Yale two tragedies befell Murry. First came the death of his beloved guardian, Isabel Clark. The next foreclosed his future: he took an HIV test. Walking back down York Street from the clinic, he ran into Yuskavage and told her he had tested positive—a death sentence in 1985. The two held each other on the street and cried.

From that point on Murry’s art underwent a sea change. He studied closely with Forge and Ann Gibson, another art historian, and with the lyrical abstractionist Jake Berthot. The most important class for Murry’s purposes, however, was also the most humbling: Bernard Chaet’s Materials and Techniques, in which the unglamorous rudiments of making art were discussed step by step. For Murry, who had dived headlong into the ideas of painting, this kind of preliminary instruction was exactly what he needed. He said the course “gave him his hands.”

The shape-driven abstractions in bright colors that Murry had previously made gave way to paintings of richly calibrated abstract atmospheres. Using his intimate knowledge of Romantic landscape from Giorgione to Rothko, he began tackling the landscape as a form through the most minimal visual syntax: the horizon as the central division on a canvas against which he could work out an endless variety of shifting atmospheric or celestial effects over a broad plane of ocean. The dynamics of light and color, of depth and surface, became a vehicle to explore the human imagination.

Advertisement

None of Murry’s landscapes was from direct observation; he sought to depict a location within the mind. In a remarkable notebook from the late 1980s titled “Windows, Walls, and Dreams,” he explained what he was out to synthesize:

I.

Poetic landscapes

ranging from places

summoned by the memory

through the imagination

II.

Dramatic pieces

where the elements

of WEATHER are protagonists

that act out moods

open to many readings

III.

Visionary works

where the light + space

have a spiritual

import

While at Yale Murry also took art history and literature classes, including a seminar with his longtime influence Harold Bloom, who had just published his study Wallace Stevens: The Poems of Our Climate. Murry used the class as an occasion to write a kind of artistic manifesto, which he later described as “the first strong formulation of my thinking as an artist and the direction my work would take.” Titled “Painting Is a Supreme Fiction: Why I Read Wallace Stevens,” it begins with the image of a “twilight interval” or “vespertinal consciousness,” which is not just the perceived transition between night and day over a landscape but the position occupied by the artist who works in modes that span the past and future, transcending historically marginalized positions as well as deadly illness. Murry argued for painting as a fictive construction, in marked contrast to the demand of modernist critics like Clement Greenberg that all literary, allegorical, and symbolic content be excluded from the canvas, leaving only yawning expanses of a liberated “color field.” Stevens’s poetry offered Murry a different attitude toward abstraction:

I know that the fiction that I call supreme is Stevens’s beautiful ecstasy which is not so much an effort to define fiction in poetry but the effort of the poet to define himself. The new inwardness which is to be our choice which is out of absolute necessity the motive of my own choosing is really a declaration of the self and its power. I see painting within this poetic dimension, not as the literary appropriation of visual fact but a manifestation or reification of the fiction of the self; and the mind through the power of imagination to progress beyond the literalness of fact to the poetic dimension of fiction. I see this as the space of the imagination. I see the space of the imagination as the only possible space for the new or poetic abstraction. I see this as the making of space where the activity of the imagination prompts a willing suspension of belief, where the viewer in the act of looking is as creative or imaginative as I am in the act of making. Painting is a poetic act.

Although fourteen years younger, Yuskavage was technically a far more advanced painter than Murry. Not only had she devoured an education on materials at Tyler, she had a keen understanding of the mechanics of form. Still, Murry was in many ways her most important teacher at Yale, because he understood the deeper significance and history of painting. Their shared obsession was color—what it was and how it worked. They each saw color as the bearer of spiritual, emotional, and social meaning. She remembers long, playful analysis of which pigments they could use for their own skin tones, Murry claiming the rich earth colors, including what they jokingly dubbed “toasted” as opposed to “burnt” sienna.

Murry experienced racism, in combination with homophobia and class prejudice, as part of the raw material of the world, but he resisted allowing these cruelties to define the liberation he was after in art, as he wrote in a poem called “From Notes on Landscape”:

All my life

has been a life of crossing

from the racial barriers

imposed by the tragic limitations of history

to the transcendental urge

to move beyond those limitations.

What has prompted this effort toward humanity

is a necessary belief in art’s saving powers of address.

This is the effort to restore imaginative possibility

along the line of the horizon,

through the space and form of landscape

as the mind recaptures its capacity to create

and the soul may regain its freedom.

By the time they graduated and moved to Manhattan, Murry had arrived at what would become his basic composition: an abstracted seascape with a slightly bowed, low horizon at an indeterminate time of day, synthesized from years of study of J.M.W. Turner, John Constable, and Caspar David Friedrich’s The Monk by the Sea, an oil painting of “great emptiness” that he saw as the true beginning of modernism. This template enabled Murry not only to engage the entire history of Western painting but also to infuse it with the content of his life as a Black, gay man, and as a poor person—an intersection horribly intensified by the AIDS crisis.

In 1989 Murry made his breakthrough work Middle Passage, a seascape in oil and beeswax on a twenty-six-by-fifty-inch canvas (see illustration at beginning of article); it was a response, in part, to Gustave Courbet’s The Mediterranean (1857), which he had studied at the Phillips Collection in Washington. In Courbet’s painting, the ocean’s dark horizon sinks slightly below center beneath a pale green sky, while foamy waves crash into a rocky shore along the lower edge of the frame. Murry made his painting much wider, so the view stretches to what would be the limit of perception; the horizon is pushed very low with no land in sight, only a copper glow above the ocean and mottled clouds. The work is a near monochrome, in the color of his own skin, and grew from his imagining of the bodies of enslaved Africans brought across the Atlantic. In his poem “A Page from the Book of Night—I,” written shortly before he painted Middle Passage, Murry reflects on these elisions between bodies and landscapes and the histories that bind them:

I will tell you

of the nights in the nights of the great mourning

when the stars were the lights of the eyes

going out in the bodies thrown over

in the crossing, in the dark Atlantic crossing

into the depths

into the place where my grief begins

over and over and never to be over.

In her own way, Yuskavage, too, had been looking for a form that could summon the brutality of her working-class girlhood. Whereas Murry was applying his ideas to landscape, her commitment was to the human figure, in particular the female nude. In The Ones That Don’t Want To: Bad Baby she painted two dark eyes in the middle of a thirty-four-by-thirty-inch canvas of searing hot pink monochrome, and then a round girlish face, with an inverted pyramid of pubic hair resting on the bottom edge. The intensity of the pink almost everywhere in the painting offered a depth where there both was and wasn’t a figure; the body was a space, a feeling.

When Murry visited Yuskavage’s studio in the East Village, he recognized that she had found a way to put all her anger and shame, the high and the low, into one seemingly simple picture. He told her she needed to “have her pussy screwed on straight” to make a painting like that, giving her a kind of motto for her future art that was irreverent, hilarious, and absolutely right. He also said he wanted to see what they’d be like at the large scale that Color Field painting often occupied.

By then Murry was becoming increasingly sick, in and out of the hospital with AIDS-related illnesses. In early 1992 he underwent surgery to remove an internal Kaposi’s sarcoma that was blocking his intestines. On her way to see him Yuskavage picked up a deep plum T-shirt and matching socks from the Gap. Murry was delighted at how beautifully the color contrasted with his skin. He told her that when he was unconscious in surgery, he heard Donna Summer’s disco rendition of “MacArthur Park” playing on repeat. He said it was like sacred music, beckoning him to heaven and holding him on earth at the same time. They couldn’t stop laughing about it, singing, “Someone left the cake out in the rain…”

That surgery gave Murry a year’s reprieve, and he got back to work in his studio on East Fourth Street. His paintings were reaching a new clarity. In his last diptych, from late 1992, he painted two twenty-inch-square canvases that initially appear to be monochrome. Abyss (Radical Solitude) is a deep plum veering into mahogany with extraordinarily subtle flashes of blue, green, and crimson, generating a dark iridescence. The horizon, the central division, has been pushed to the very bottom edge of the painting. Rising works its way up from the exact tone of Murry’s skin into an atmosphere of tawny light that shimmers with green and pink. During his last studio visit, with his friend Candida Smith, he pointed to the painting and told her that with this one he’d said everything he needed to.3

For Murry, confronting illness and death inspired an outpouring of poetry. In January 1993, shortly after finishing Abyss and Rising, he was admitted to the hospital with a sudden sickness. He found himself unable to speak and wrote out a string of poems, ten pages of jewel-like meditations reporting and reflecting on the experience of dying. The movements of light and darkness in his words communicate the experience of suffering, the will to live, as well as the promise of transcendence within the mind:

In-clusivity

the beautiful freedom

of ultimate choice

how even death

transfigures

darkness

as the dying out of

the body becomes

the dying into light.

On January 13, 1993, Yuskavage, Murry’s partner George Centanni, and a couple of friends went to see him in the intensive care unit, staying late into the night. They had dinner at a nearby pub, held hands, and prayed for him. On the way home, Yuskavage picked up a white candle from a bodega and put it in her window. Lighting it, she wrote to him in her journal, “It’s OK to just let go.” A few hours later, in the early morning, something woke her up. She called the hospital, saying she was Murry’s sister. The nurse told her that Jesse Murry had died.

Murry’s friends moved forward with the arduous work of burial and memorial; he had no relatives to help make the legal decisions. The year before, Yuskavage had attended Act Up meetings and learned how to organize an artist’s estate. Together, she and Centanni set about cataloging and packing Murry’s studio, moving his paintings into a storage unit on 23rd Street. Centanni xeroxed all of his notebooks and whatever writing he could find and gave packages of them to Murry’s closest friends.

Back in her studio, Yuskavage grieved and remembered Murry by painting. She started a monochrome, thinking of him laying in bed with his purple Gap shirt and socks, laughing about that Donna Summer song. She laid out a ground of luminous, deep purple and out of it coaxed the body of a little Black girl, wearing a simple dress with a white collar. The girl’s arms are gently clasped in front of her; her eyes are open and look back at the viewer, as though she’s lost, questioning. The painting, titled The Ones That Don’t Want To: Black Baby, was a secret portrait of her friend. Yuskavage’s other monochrome Bad Baby paintings were full of anger and confusion, fueled by sex and revenge. But this one portrayed sorrow—sorrow at Murry’s vulnerability, the improbable beauty he had made his life into, and how that was all taken away.

In his studio at the time of his death, Murry had a six-foot-square blank canvas that he had made plans for but never found the strength to tackle. Centanni gave it to Yuskavage and helped carry it down Avenue B to her studio. Murry’s words about how her paintings needed to assume the scale of Color Field hovered over it, and she set about making her first large painting since she was a teenager. First she covered the entire expanse in cadmium scarlet, which at that size created a palpable heat coming off the canvas. In a closely related color she formed a curved figure sitting on the bottom edge and smoking a cigarette. Big Blonde Smoking was both body and abstraction—color and light as a space for thinking and feeling, the figure staring back while diaphanous smoke trailed from her mouth. It was painting as a fiction, as nonnarrative poetry, the way she and Murry had long discussed.

This Issue

December 2, 2021

Grand Illusion

‘And I One of Them’

Herring-Gray Skies

-

1

Much information for this piece was drawn from interviews with Jesse Murry’s friends, including Lisa Yuskavage, George Centanni, Rebecca Smith, Candida Smith, Peter Stevens, Meg McMorrow, Matvey Levenstein, James Cambronne, Joy Episalla, Bradford Harding, Carrie Yamaoka, and Clay Hapaz, among others. ↩

-

2

Jesse Murry, “Art History, Poetry, Philosophy, Painting,” in Painting Is a Supreme Fiction: Writings by Jesse Murry, 1980–1993, edited by Jarrett Earnest, with a foreword by Hilton Als (Soberscove, 2021), p. 34. ↩

-

3

Lisa Yuskavage and I curated an exhibition of Murry’s work, “Jesse Murry: Rising,” at the David Zwirner Gallery, New York City, September 17–October 23, 2021. ↩