A few years after publishing his superb translation of Dante’s Purgatorio (2000), W.S. Merwin told me he was toying with the idea of also translating Paradiso, but added that he had some reservations. The first was that the canticle contains an encomium of Saint Dominic, who in Merwin’s eyes was the most villainous churchman of the Middle Ages. Dominic had zealously promoted the Albigensian Crusade, which over a twenty-year period in the early thirteenth century barbarically stamped out Catharism and put an end to the vibrant and beautiful court culture of southern France. Merwin had purchased a farmhouse in Languedoc as a young man and was fiercely attached to the region, where the troubadours, alongside the Cathar “heretics,” flourished during the twelfth century. Like many people there today, he bitterly resented the Albigensian Crusade, which claimed hundreds of thousands of innocent lives (by some estimates close to a million).

Merwin’s second reservation had to do with his antipathy toward Dante’s guide through the nine heavenly spheres. I agree with him that in Paradiso Beatrice comes across as a pedantic, irksome character who treats the pilgrim like a wide-eyed child. The Beatrice of The Divine Comedy has little to do with the historical woman who inspired such beautiful poems in Dante’s earlier work Vita Nuova.

I urged Merwin to go ahead and translate Paradiso, since it contains some of the most sublime poetry of the Western canon, which only a poet of his caliber could do full justice to in English. In the end he decided against it. “I just don’t love it enough,” he said.

Given Merwin’s excellent version of Purgatorio, plus dozens of others in English, the only reason to undertake yet another translation of it—or any other part of The Divine Comedy, for that matter—is love. “Love makes me speak,” as Dante said, and the seven hundredth anniversary of his death has brought three new translations of the second canticle, all of them by poets enamored of it. Mary Jo Bang’s Purgatorio comes eight years after her equally sparkling rendition of Inferno. The new translation by the Scottish poet and psychoanalyst D.M. Black is on a par with Merwin’s.* And if that weren’t enough, sixteen different poets, including Bang, contribute to After Dante: Poets in Purgatorio, which, in the words of one of its editors, Nick Havely, “render[s] the Purgatorio in a number of different voices, reflecting a range of contemporary cultures, concerns and techniques.”

One reason poets tend to cherish Purgatorio is because in it Dante meets a host of fellow poets and reflects on the wonders of literary history. In Purgatorio 21, for example, he and Virgil encounter the Roman poet Statius, who declares to the still-unidentified wayfarers that Virgil’s Aeneid “was my mother/and my nurse too in making poetry:/without it I would not have weighed a dram.” When it’s revealed to him that he is in fact in Virgil’s presence, Statius is seized with rapture and veneration. He tells Virgil that the prophetic verses in his Fourth Eclogue—“Time is renewed…a new progeny descends from heaven”—were responsible for his conversion to Christianity, hence for his salvation. To Statius, Virgil was like “one who walks by night and bears/a lamp behind him, not to help himself/but to give light to those who follow after.”

In that beautiful image of one poet following in the footsteps of another, the follower is saved while the forerunner is not. (Virgil returns to his abode in Limbo after his trek through Purgatory.) Statius declares, “Per te poeta fui, per te cristiano” (“Through you I was made poet; through you, Christian”). In Dante’s universe no person can give another more than that. Nor does it much matter that the historical Statius almost certainly did not convert to Christianity. Dante contrived that story to express his own immeasurable gratitude to the poet who came to his rescue in the dark wood of Inferno 1, and whose Aeneid put him on the path to becoming an epic poet.

Poets are not the only ones who love Purgatorio. Most readers who make it that far into The Divine Comedy find its deeply human and terrestrial spirit enchanting. Whereas Hell has no stars, sunsets, or seashores, on Mount Purgatory we are once again under the open sky, where the sun’s movement marks the hours and seasons; where night gives birth to day, and day dies into night; and where the shimmering seas of the southern hemisphere surround the island from all sides.

A palpable terraphilia informs the canticle. We find here a love of the planet and everything that makes it our cosmic home—its rivers, valleys, seas, and mountains; its diurnal cycles; its ever-changing light and color; and above all its celestial dome. Not to mention its plant life. After Dante enters the earthly paradise of Eden at the summit of Mount Purgatory, the fair Matelda informs him that he has risen above Earth’s zone of meteorological disturbance. The gentle breeze that graces the ancient forest of Eden comes, she says, from the heavenly spheres as they move from east to west around the planet. This rotational wind scatters seeds from the flora of that primal place to the rest of the planet below: “And then the Earth, according to its character/and where it is beneath the heavens, conceives/and by its various powers bears various plants.” In sum, all the plant life of our burgeoning, self-renewing biosphere has Edenic origins.

Advertisement

The shades in Purgatory have much to look forward to and work toward—salvation awaits them at the end of their penances—yet the first nine cantos of Purgatorio are filled with the pathos of loss and backward glances (“It was already the hour at which the sailor’s/longing remembers home and his heart softens,/having that day said farewell to his dear ones”). The opening cantos contain wistful accounts by various shades about the fate of their mortal remains, which were buried, lost, exhumed, or reburied back on Italian soil. A profound nostalgia for embodied life and the loved ones whom time and death have separated from the recently departed pervades the “body biographies” of the souls in Ante-Purgatory.

Dante’s pilgrim, fresh out of Hell, shares that nostalgia. When a newly arrived shade reaches out to embrace him in Purgatorio 2, he eagerly responds with the same gesture. Three times he tries to hug the shade, and “three times behind him my hands clasped each other/and…returned to my own breast.” Dante forgets that he is dealing with an “empty shade” and not a human body. The spirit smiles and moves back a little. Dante steps forward. The spirit holds him back: “Soavemente disse ch’io posasse.” If I had to choose the most beautiful verse of The Divine Comedy, it would be that one. In Black’s translation: “And he then, gently, asked me to stay still.” In Bang’s: “He gently told me I should let it go.” Bernard O’Donoghue: “Gently he told me I must take it easy.” The verse is as suave as the word soavemente, which the English “gently” conveys only in part.

The scene has two classical precedents. In book 11 of the Odyssey, Odysseus attempts to embrace his mother’s shade three times and comes up empty-handed. Aeneas repeats Odysseus’s gesture with the shade of his father, Anchises, in Hades, in book 6 of the Aeneid. In Dante’s case, it is the shade of a friend, or better, of a fellow human being who turns out to be his friend Casella. What often goes unnoticed in the scene is that only following his failed embrace does Dante recognize Casella, evidence enough of how starved he is for human affection after his journey through Hell. This is not by chance, for Purgatorio figures as the canticle of friendship par excellence. In Hell, no matter how near to one another the sinners may be, there are no bonds of friendship (with the possible exception of the three noble Florentines in Inferno 16). The regenerative moral sanity of Purgatory manifests itself in the goodwill that binds all its souls, whether they knew one another in life or not, in communities of fellowship.

Whereas Hell and Paradise perdure eternally, Purgatory did not exist before the Incarnation and will cease to exist come Judgment Day. In that respect it resembles our own finite human lives, which begin and end in time. The penitents on the mountain’s seven terraces purge their sins in days, years, and centuries. In due time each one of them will graduate from one terrace to another, and beyond. The sinners in Hell, by contrast, remain forever without prospect of release. It is the difference between the foreclosure of despair and the expansiveness of hope. We humans dwell in the openness of time, and Purgatory is the only realm in Dante’s Comedy where time matters.

Dante had journeyed through Hell as an insomniac, experiencing the sort of nightmarish visions brought on by prolonged sleep deprivation. In Purgatory he and Virgil are under strict orders from the angelic guardians of the realm to halt their ascent of the mountain toward evening and, at least in Dante’s case, to sleep at night. On each of the three nights he spends on Mount Purgatory, Dante has vivid dreams, and with each new dawn he wakes up restored.

Advertisement

Indeed, restoration marks the very purpose of the purgatorial process. While Hell figures as a great gash in the body of Earth, where all the vices that disfigure the soul and human history fester, Purgatory is where the slow, laborious work of healing takes place. Dante, whose pilgrim arrives on the realm’s shores on Easter morning, calls it the soul’s rebeautification (“Creature who cleanse yourself/to go back beautiful to your Creator,” he addresses a penitent in Purgatorio 16). The penitential ordeals of Dante’s Purgatory—many of them as harsh as the punishments in Hell—are intended to restore the prelapsarian probity of human nature and prepare the way for a return to Eden, which Dante locates at the mountain’s summit. Dante himself will enter Eden at the end of his journey through the second realm, and so will all the other penitents after completing their purgation. From that garden of recovered innocence they too, like Dante’s pilgrim, will ascend into heaven.

The transition from Hell to Purgatory marks a shift from the psychic depths probed by Dante’s Inferno to the remedial ethics represented in his Purgatorio. Nothing—not even Shakespeare’s soliloquies—can compete with the devious, self-serving, and self-deceptive psychology of the speeches Dante devises for his sinners in Inferno. Black offers a psychoanalytic interpretation of Purgatorio in the commentary to his translation, yet psychoanalysis has a great deal more to work with in Inferno than in Purgatorio. To adopt a psychoanalytic distinction of my own, I would say that Dante’s sinners in Hell “act out” the psychology of their punishments, while the penitents in Purgatory “work through” the ordeals of their self-overcoming.

Purgatorio in fact suggests a behavioralist rather than a psychoanalytic approach to rehabilitation. Dante shared the medieval Christian notion that vice entrenches itself in habits, and like most behavioralists he knew that nothing is more difficult to alter than habits or states of mind that have become deeply ingrained over time. In Dante’s Purgatory the penitents labor to reform impulses and behaviors that, over a lifetime, have hardened into quasi-innate dispositions.

The penitents could not redirect their behavioral habits and desires in such a manner, transmuting self-love into love of the common good, if the human will was not intrinsically free. Dante understood the will’s freedom in a Christian sense: not as freedom to do as we choose but the choice to submit or not to submit to the dictates of divine dispensation. In one of the most pregnant formulations of the Comedy, the character Marco Lombardo declares to Dante, “A maggior forza e a miglior natura/liberi soggiacete.” In Black’s version: “To a greater force and to a better nature/you, although free, are subject.” In Bang’s more compact, and in some ways more exact, rendition: “You’re the free subject of a greater force,/And a better nature.” The “you” here refers to human beings in general.

Marco Lombardo’s disquisition on free will, human nature, and the moral good takes place in the middle canticle’s middle cantos, that is to say at the very center of The Divine Comedy, for the main preoccupation of Dante’s poem revolves around the problem of misdirected love, as well as human history’s abysmal failure to take its directives from the mandates of human and divine justice. Through the speeches of Marco Lombardo and Virgil in the poem’s central cantos, Dante attributes wayward love not to the stars or an inherent depravity of human nature, but to bad education, lax enforcement of just laws, and forms of government that promote rather than restrain human cupidity. All in all, he had a sane, sociopolitical, behavior-based understanding of the causes of human wrongdoing.

These new translations all do justice to the tone, semantics, and forward-moving rhythm of Purgatorio. Accurate, lyrical, and unmarred by literary overreaching, Black’s version succeeds in conveying “the movement of Dante’s thought,” as he defines his aim in his introduction. His version is also the only bilingual edition of the three (an important consideration for those of us who teach The Divine Comedy at the college level).

It is not easy to lighten Dante’s poem in English, which lacks the musical sonorities of Italian, yet Bang brings to her translation a remarkable lightness of spirit that I find refreshing and at times delightful. As with her translation of Inferno, she deploys a number of contemporary references (“the next realm…/is here where the human spirit gets purified/and made fit for the stairway to Heaven”). In her more jarring “contemporizing moments,” she uses phrases like “every Tom, Dick, Harry, Moll, Nell, and Sue,” or inserts a phrase from “America the Beautiful” into the speech of a character.These anachronisms have the simultaneous effect of familiarizing as well as defamiliarizing Dante’s poem, yet without mutilating it. Her vibrant and often playful rendition remains faithful to the spirit if not always the letter of Dante’s poem.

For the most part, the sixteen contributors to After Dante also ably negotiate the demands of accuracy on the one hand and poetic lift on the other. Some, like Bernard O’Donoghue, Angela Leighton, and Steve Ellis, translate multiple cantos, while others, like Jonathan Galassi with his exquisite version of Purgatorio 18, contribute only one. Where liberal license is taken with the original—as in John Kinsella’s translation of Purgatorio 32—the poetic achievement more than compensates.

If there was ever a good time to bring out inspired new translations of Purgatorio it is now, when the inveterate vices of human civilization are disfiguring our planetary body and body politic. The world stands in need of this canticle’s message of rehabilitation, reconciliation, and regeneration. The rapture of Paradise is beyond us, and the despair of Hell would spell the end of the modern world’s promise of freedom. It’s the middle region of Purgatory that speaks most directly to the self-inflicted wounds of our present condition, whose deeper causes Dante diagnosed with moral clarity seven hundred years ago. I for one would not quarrel with his claim that most of the world’s woes are due to human cupidity, or with his insistence that only robust social and political institutions—and the proper enforcement of just laws—can restrain our worst impulses.

Among all the new Dante commentaries, conferences, festivals, and translations of 2021, one publication in particular stands out as truly momentous: Rachel Owen’s Illustrations for Dante’s “Inferno.” Not since Salvador Dalí’s one hundred watercolors of The Divine Comedy (1951–1960) and Robert Rauschenberg’s equally extraordinary transfer drawings of Inferno (1958–1960) has an artwork reimagined Dante’s netherworld with such novelty and originality. Owen’s volume contains thirty-four illustrations of Inferno and six of Purgatorio, along with essays by her friend and fellow artist Fiona Whitehouse and the Dante scholars David Bowe and Peter Hainsworth, as well as translations of two cantos of Inferno by Jamie McKendrick and Bernard O’Donoghue.

Once these illustrations begin to circulate, Rachel Owen will become a much better known artist. After majoring in Italian and fine art at the University of Exeter, she studied art at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence, where her lifelong love affair with Dante began. She wrote a Ph.D. thesis entitled “Illuminated Manuscripts of Dante’s Commedia (1330–1490)” and went on to teach art history and medieval Italian literature as a lecturer at Pembroke and other Oxford colleges. Even before finishing her doctorate in 2001 Owen had produced three series of prints inspired in part by Dante’s poem. She planned to illustrate the entire Divine Comedy much earlier, yet did not begin the project until 2012, four years before her untimely death from cancer at age forty-eight.

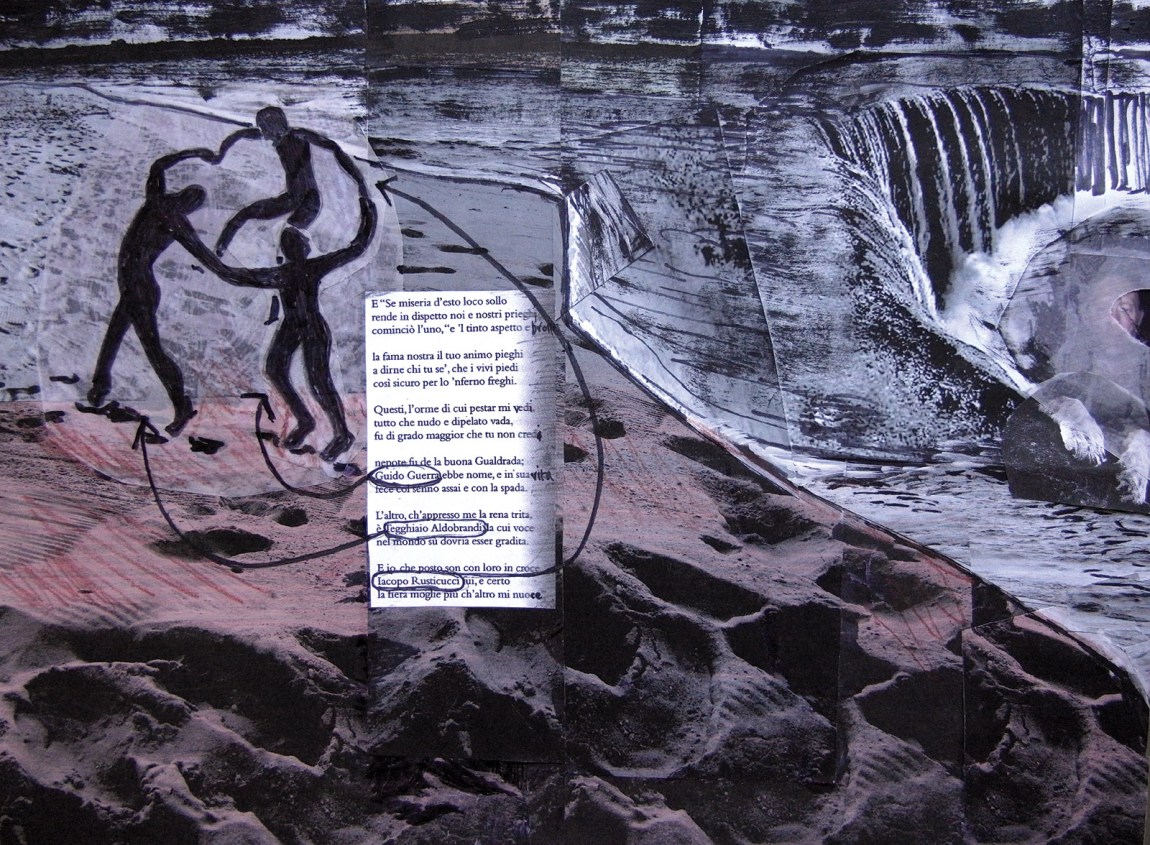

Owen’s photographic prints are mixed with found materials and coloring markers of various sorts. Whitehouse explains in her accompanying essay how the images derived from collages of cut-up and glued photographs, photocopies of text, and tracing paper, to which Owen applied acrylic paint, different pen inks, chalk, colored pencils, white-out corrector fluid, and gold and silver paint. Some of the images contain written texts. The original collages—not intended for exhibition—were photographed, reduced in size (thus rendering the contrasts and colors more vivid), and then printed.

Much as William Blake’s drawings did two centuries ago, Owen’s photographic prints reveal just how unbounded Dante’s afterlife is when imaginative artists reenvision it. Owen’s are the only illustrations of the Comedy in which the figure of Dante never appears (occasionally we see his garment or a body part); rather, we see what the wayfarer himself sees; or better, we see what the artist who puts herself inside Dante’s eyes sees as she moves from canto to canto. Tom Phillips writes in his blurb that Owen’s images “create what seem like daring stills from a film noir of Dante’s journey.” This puts it well, for the images have an extraordinary kinetic quality as the viewer progresses from one to the next. There is a distinctly flowing effect as one turns the pages. It is not by chance that Owen introduces the presence of water—above all flowing water—in scenes where Dante’s poem has none, almost as if it’s the fluid in the artist’s eye that does the flowing.

Just as Dante introduced a number of autobiographical elements into his poem, Owen personalizes her journey by inserting into his infernal landscapes images and shadow cutouts of family members and friends, as well as of herself. Superimposed on the image of a sarcophagus in the cemetery of the heretics, for example, a photo of her young, slender, and long-haired son stands, incongruously, for the supercilious nobleman Farinata degli Uberti. The son’s silhouette also figures the three usurers whom Dante encounters in Inferno 17. Owen’s daughter makes several appearances, one of them as a toddler in the arms of her mother, in a photo that Owen inserted tenderly into a scene of Dante’s lake of ice at the bottom of Hell. Whitehouse figures in profile as the beautiful Francesca of Inferno 5.

In an evocative, overexposed photo of her own face, Owen herself gazes out at us from a lower corner of her illustration of Inferno 2. She most likely represents Beatrice, yet the self-portrait almost certainly also alludes to the biblical Rachel, who sits next to Beatrice in heaven, as Beatrice informs Virgil in that canto. Some of the other illustrations feature cutouts of Owen’s shadow and outline.

Whitehouse mentions that the waterfall in Owen’s illustration of Inferno 16, which flows from the circle of violence into the abyss of Malebolge (the circle of fraud), contains a photograph of Owen’s “estranged husband,” to which she added the feet of a lion (see illustration above). The photo of his face is so faint and discreet as to be practically invisible. Deliberately so, one must assume. No one reading the essays in this edition would know that Owen was the longtime partner of Thom Yorke, the singer and bandleader of Radiohead and father of her two children. The discretion is admirable, yet I believe their relationship has some pertinence. Yorke and Owen met at the University of Exeter as undergraduates in the early 1990s and separated in 2015, a year before Owen died. In light of Whitehouse’s cryptic remark that some of Owen’s self-portraits in the collection “are difficult to look at, reflecting as they do her own painful, inconvenient and infuriating situation,” one wonders to what extent Yorke may hover like a mostly invisible ghost over the personal testament that informs the collection as a whole.

That Owen did not live to finish illustrating the entire Divine Comedy represents a great loss. Whitehouse puts it best when she describes how she and Owen’s parents found six folded collages in a box high on a bookshelf after Owen died:

We unfolded them and saw that they corresponded to the first six cantos of the Purgatorio. The images are full of love, laughter and colour reflecting the changed atmosphere of the verse, which leaves behind the poetry of the damned. Seeing the images for the first time was a deeply emotional experience. I had come to believe that the end of Rachel’s life had somehow mirrored parts of Dante’s Inferno, but these images offered a different narrative.

Those images leave little doubt that Owen’s reenvisionings of Dante’s second and third realms would have been altogether luminous, thought-provoking, and even ecstatic. We are fortunate to have illustrations of the first six cantos of Dante’s middle canticle, for they make it abundantly evident that the love that moved the translators of these new versions of Purgatorio also moved Owen to become a companion on Dante’s journey to redemption. Those six post-infernal images offer a narrative very different from the ones of the damned. There are just enough of them to show that we’re all on this mountain together.

This Issue

December 16, 2021

Exhilarating Antihumanism

Nicaragua’s Dreadful Duumvirate

-

*

Parts of this essay are drawn from my preface to Black’s translation. ↩