Editor’s Note

After publication, we were informed that this posthumous essay previously appeared in The New Republic in 2002. Nina Howe explained the circumstances of its rediscovery in a letter in our February 10, 2022, issue.

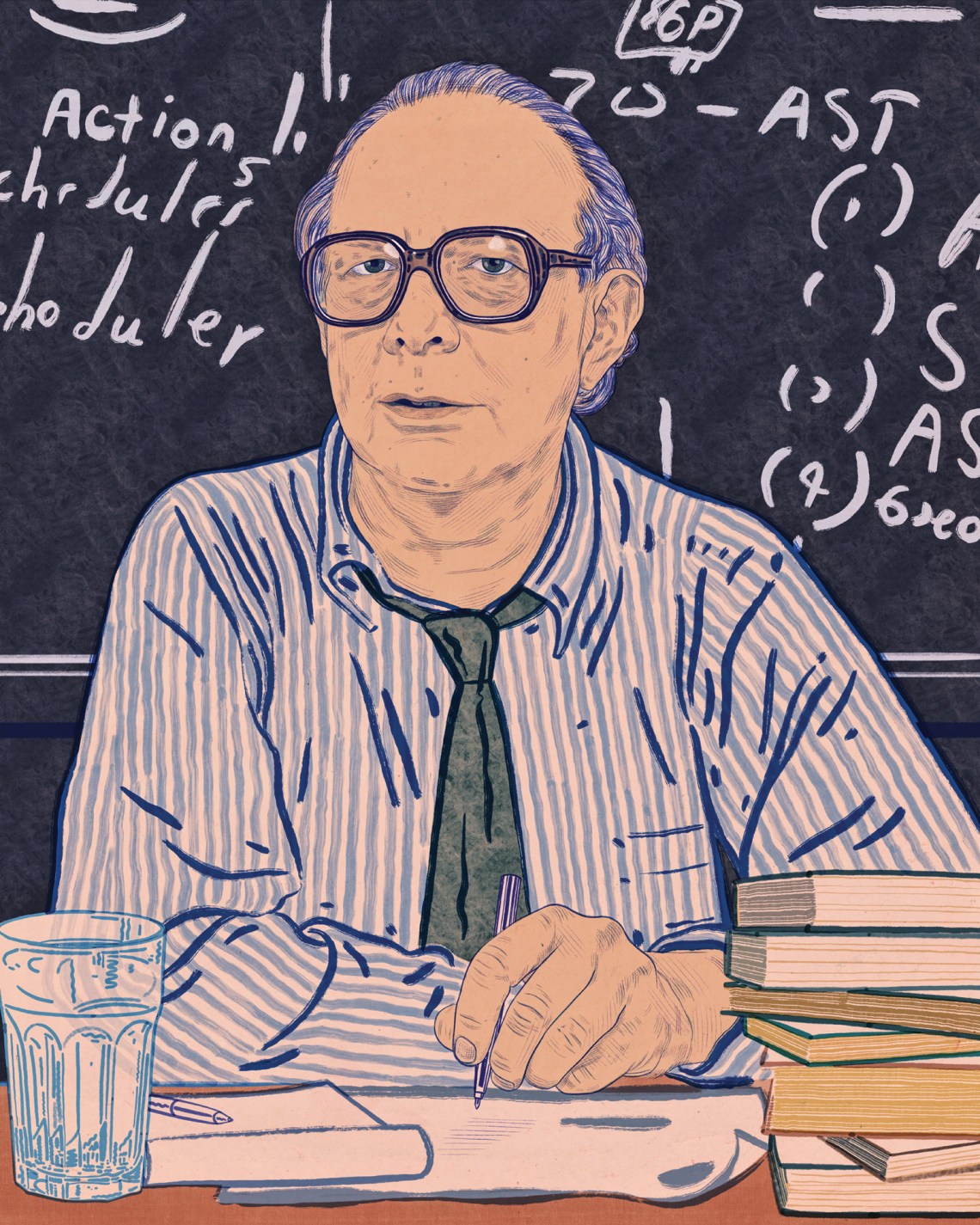

My father, Irving Howe, wrote this essay on Isaac Babel in the late 1980s, so far as I can tell, as the introduction to a book of Babel’s stories that Patricia Blake had planned to edit. The book was never published, and my father apparently tucked the introduction away in a drawer in his apartment. At the time of our father’s death, in 1993, my brother, Nick, began to collect the unpublished essays that subsequently appeared in the posthumous A Critic’s Notebook. Nick was aware of the Babel introduction and wanted to include it but could not find it; only recently did our father’s widow, Ilana Weiner Howe, come across the manuscript. Given my father’s long history with The New York Review, starting from its very first issue, he would have been amused to know that his essay on Babel now appears in these pages.

—Nina Howe

Speak the name of Isaac Babel and one phrase comes insistently to mind: a writer of genius. But what we might mean by “genius” is not easy to say. William Hazlitt wrote that “the definition of genius is that it acts unconsciously,” by which I take him to mean that genius is a gift pouring through the writer—pouring through because it seems to come not merely from his own creative resources but from “somewhere else.” In the case of Babel this gift is not nearly so abundant as in, say, Keats or Proust; it is narrow in scope, tensely packed, austerely situated. Babel’s career as literary craftsman was spent in the hard labor of endless revision, a subtle refining and compressing of violent effects. Yet what strikes one first and last is the glow of a great natural talent, a blessing bestowed. And for all his labor, Babel’s art is finally an art of risk: either success or failure, with no space for modesty.

Born in 1894 in Odessa, Babel came to maturity at about the time of the Russian Revolution. In the 1920s he gained a reputation as an important Soviet writer, in part through a cycle of Odessa stories—thickly colored, farcical tales of Jewish gangsters—and in part through a sequence of stories and sketches called Red Cavalry (1926), set in the now forgotten Russo-Polish War of 1920 as seen through the eyes of a Jewish intellectual, pacific and melancholy, with “glasses on [his] nose…and autumn in [his] soul”—a version of Babel himself. Mainly through a mastery of silence Babel survived the opening years of Stalinist terror until his arrest by the secret police in May 1939. Exactly why he was arrested we do not know; in those terrible years there often was no “why.” Interrogation and apparently torture followed, then a secret “trial” and execution in January 1940. For many years afterward, the exact circumstances of Babel’s death remained unknown; but as a mercy of glasnost, reports about his last days have begun to appear in Soviet periodicals.

Babel was raised in a lower-middle-class Jewish family wavering between religious habits and secular inclinations. In those years Odessa was an especially lively city containing within itself the social tensions and clashing ideas of prerevolutionary Russia, and in the stories of his childhood Babel brings together a wild mixture, almost a fantasia, of motifs: Jewish fears of pogroms, the pressures of burgeoning sexuality, an early liking for Western culture, admiration for plebeian rowdies. Nor does he try, through will or formula, to bind these motifs into harmony—harmony would never be, for him, a major desire. In the stories about Benya Krik, the stylish Jewish gangster reigning as “king” of Moldavanka, a poor Odessa neighborhood, the tone is charmingly buoyant and frequently mock-heroic. Benya, after all, is no more than a small-time thug, but when elevated to local legend he comes to represent amoral pleasures and energies that the bookish Jewish narrator wistfully aspires to. This narrator tries to ferret out the secret of Benya’s personal authority (see the brilliant story “How It Was Done in Odessa”), but all he can do is stare from a distance.

The Benya Krik stories bear an aura of extravaganza, of playful excess, somewhat like a comic opera, and indeed, when reading them one recalls John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, perhaps also Bertolt Brecht’s Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera), both nose-thumbers. In one of Babel’s stories, Benya Krik, delivering a funeral oration over a poor clerk “accidentally” killed during a holdup, grandly declares the victim to have “died for the whole working class”—whereupon the piece comes to a gloriously absurd climax as “the sun stands to attention over [Benya’s] head like a sentry with a rifle.” (In Yiddish fiction of the early twentieth century there is a similar fondness for rowdies, even thieves, as figures of social combativeness overcoming traditional Jewish passivity and fear. Whether Babel was familiar with these writings I do not know; but he certainly knew Yiddish.)

Advertisement

About his early years Babel writes in an abbreviated “Autobiography”:

I was born…the son of a tradesman Jew. On father’s insistence, I studied Hebrew, the Bible, the Talmud, till the age of sixteen. Life at home was hard because I was forced to study a multitude of subjects. Resting I did at school.

Babel’s Jewish upbringing left upon much of his work a stamp of affectionate irony, sometimes embarrassed nostalgia. In a number of stories it seems to me that one can detect a sly rendering of Yiddish speech melody, a sort of vibration of inheritance, beneath the surface of the prose. The early piece “Shabos Nakhamu,” a slender folklike anecdote, reads like an apprentice mimicry of Sholem Aleichem.

By 1915 Babel had made his way to Petrograd, living as a bohemian and trying to get his early writings into print. He submitted a few stories to Maxim Gorky, then a famous writer, and the generous older man quickly recognized Babel’s large, still unformed talent. That Gorky published these pieces in the newspaper he edited, Babel would later recall, was a crucial event in his life. Then, between 1917 and 1924,

I served as a soldier at the Rumanian front, in the Cheka [as a clerk in the Bolshevik secret police], in the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment…in the First Cavalry Army [with the Cossacks during the Russo-Polish War]…. And only in 1923 did I learn to express my thoughts clearly and concisely. Then I once again began to compose fiction.

By the mid-1920s Babel had become a central figure in the ill-fated generation of modernist Russian writers who for a time hoped to strike a truce with the Bolshevik regime—later, almost all of them suffered from the cultural despotism, often the sheer brutality, of the Stalin dictatorship. Babel’s work in those years can be seen, in part, as a fulfillment of the critical program advanced by the Soviet writer Yevgeny Zamyatin in a dazzling essay called “On Literature, Revolution, Entropy, and Other Matters”: of a clenched blow of narrative, a repressed turmoil of emotion, a wounding entanglement with history, a rejection of familiar answers. But together with the literary persona who employs devices of shock, enigma, and compression, there is another Babel, a “natural” storyteller, the literary grandson of the Yiddish masters Aleichem and Mendele Mocher Sforim. This Babel speaks with relaxed guile, a friendly grin, even now and then a few words of tenderness.

Red Cavalry is Babel’s major achievement, the book that immediately thrust him into the front rank of twentieth-century literature. It strikes me as, in the literal sense, a terrible book, one that sends tremors of pain through the heart. It’s also a book rarely settled or comforting in its moral stance, always stopping before or stalled at puzzlements and quandaries. The usual paraphernalia of literature are stripped away: no expository preparation or firm authorial guidance, no delicate psychological analysis, no hankering after philosophical depths. All comes across as a brilliant glare of surface, with repeated climaxes that are sometimes preceded by brief colorings of imagery and sometimes by a brief calming of voice. Lyutov, the narrator—he’s the same fellow we met before, glasses on his nose, autumn in his soul—is attached to a Cossack unit in the 1920 Bolshevik campaign against Poland.

Babel’s actual experience lies behind these stories, but he is also drawing on a literary tradition celebrating the primitive graces of the Cossacks. In Tolstoy’s romantic-pastoral novella The Cossacks, a nervous young man from Moscow who has settled for a time with a Cossack community learns to value its “natural” ways of living, its freedom from pretension, snobbism, and anxiety. Babel’s Cossacks are drawn in harsher tones and darker colors than Tolstoy’s, since Babel could hardly have forgotten how strongly Russian Jews feared the Cossacks, who were often participants in pogroms. (See the story “First Love.”) In a 1920 diary Babel wrote, “What is our Cossack? Layers of trashiness, daring, professionalism, revolutionary spirit, bestial cruelty.” But, he added, the Cossacks exhibit “an awesome force,” an “unutterable beauty,” and have a gift for “magnificent comradeship.” Like Tolstoy before him, Babel admired the Cossacks’ ease of movement, their ready acceptance of inherited modes of life, their distance from the traumas of modern consciousness—so strikingly different from the ghetto Jews who “moved jerkily, in an uncontrolled and uncouth way.” Finally, however—if one can ever speak of anything final in Babel’s work—he is torn in his feelings about the Cossacks: he does not quite yield to a myth of the noble savage, he recognizes the Cossacks’ wanton brutality, he must live with the Odessa self-consciousness that is his lot.

Advertisement

In Red Cavalry, primitive Cossack ways jostle against the unhealed consciousness of the narrator. The random brutality that is a heritage of centuries seems now, through an act of revolutionary will, to be lifted toward a selfless communist heroism; but this soon succumbs to an old brutality that has survived into the present. Extremes of behavior, weaving into one another as if to spite moralists, bewilder the narrator. They bewilder us too. Nothing in Red Cavalry is fully resolved; contraries battle one another into the last page.

Babel the writer was drawn to violence, its decisiveness, its absoluteness. This may partly have come from a personal inclination that it would be presumptuous to explain by long-distance psychology. But it was also, perhaps mainly, a response he shared with many younger Jews of his time who felt that only forcible resistance could halt the repeated attacks upon their people. There is enough evidence in Babel’s writings and letters to make clear that personally he also detested the violence to which as a writer he was drawn. Ambivalence—that may be too mild a word—glares out of his pages, the sign of clashing sentiments and desires. He lived intimately with division; he had no other home. And this division derived from sources deeper than any views he may have held about the events of his time; it betokened a kind of imaginative largesse, a generosity of response toward all those who were forced to endure the blows of history—Cossacks, Hassids, commissars, old women trapped in war. If he seems at times to be a partisan in thought, he was free of bias regarding all who suffered.

Yet he felt a strong need to identify himself with—even as he kept an uneasy distance from—a powerful current of history: the rebellion surging through Russia in 1917. He belonged to no party, and in his later years he must surely have had caustic judgments about Stalinism. But during the decade after the revolution, when he did most of his best work, it seemed to Babel, as it seemed to other Russian writers not necessarily sympathetic to Bolshevism, that Russia was experiencing another of its recurrent waves of primal upheaval. In such a moment, violence seemed inescapable, violence as the spur of history. Enough time has passed in which to form critical judgments of such attitudes, but if we are to read Babel and many other gifted Russian writers of the 1920s, like Mayakovsky and Pilnyak, we must find in ourselves the historical imagination to grasp the shattering circumstances in which they wrote. We have to see, if we cannot share—we have to read as if we see what they were experiencing.

Glance at “My First Goose,” one of his marvelous shorter stories, where the narrator, joining a Cossack squadron, suffers a rude hazing—immediately the Cossacks see he is not one of them—until, desperate to show himself worthy of their esteem, he orders the woman in whose house they are quartered to cook him something to eat. “Comrade,” she replies, “all this business makes me want to hang myself.” A few lines later she repeats her remark. What she says serves as a moral counter to both the Cossacks and the narrator; it comes to seem a choral plaint for the whole of humanity.

Lyutov-Babel kills a goose and forces the woman to cook it for him. Admiring this show of toughness or, as they would regard it, manliness, the Cossacks welcome “the lad” to their circle, and in return he reads them a speech of Lenin’s “in the loud voice of one defiantly deaf.” The story ends:

After that we went to bed in the hay-loft. There were six of us sleeping there, keeping each other warm, with our legs entangled, under a roof full of holes that let in the starlight. I dreamt, and there were women in my dreams, but my heart, my scarlet murderer’s heart, creaked and bled.

It’s an astonishing ending. The narrator’s legs become “entangled” with those of the Cossacks in a fraternity of sleep, but he judges himself to be a “scarlet murderer,” unfaithful to his true self, for in his heart he is a man of peace. And like a rasp of communal grief, there is the voice of the woman: “Comrade, all this makes me want to hang myself.”

Red Cavalry turns on Babel’s struggle with a problem that must trouble any writer of fiction who deals with political life: the problem of historical action in both its (perhaps) necessity and its all but certain self-contamination; that is, the flaw at the heart of an action that by virtue of being in history must to some extent be conceived in violence and thereby end as a denial of itself.

Some of the most powerful stories in Red Cavalry turn against the narrator—his inability to kill other men and sometimes his feckless attempts to mimic the ways of those who do know how to kill. The Jewish literary man needs to prove to himself that, given the historical necessity, he can commit acts that for the Cossacks seem second nature. Does Babel sentimentalize the Cossacks here? By and large, I’d say no. He realizes that finally he can neither understand nor join them. What makes these quivering little stories so remarkable is that Babel knows he must grant cogency and force to all sides in the conflicts he depicts, but especially must he allow the Cossacks to be neither romanticized nor devalued by the narrator’s judgments. The stories live through inner opposition.

In a brilliant five-page story called “The Death of Dolgushov,” a wounded Cossack, his entrails hanging over his knees, begs the narrator to shoot him, but, soft and scrupulous, the narrator funks it. A comrade of the wounded man does the job and then turns on Lyutov-Babel in a fury: “You guys in glasses have about as much pity for chaps like us as a cat has for a mouse.” The moral stress here is clearly in favor of the Cossacks, who feel, with some justice, that the sensibilities of the intellectual keep him from doing a terrible thing that is nonetheless the humane and necessary thing. In another five-page masterpiece, “After the Battle,” a Cossack curses the narrator for having ridden into battle with an unloaded revolver (“You didn’t put no cartridges in…. You worship God, you traitor”), and Lyutov-Babel goes off, “imploring fate to grant me the simplest of proficiencies—the ability to kill my fellow-men.” And at the end of Red Cavalry another Cossack pronounces upon the narrator a primitive judgment—“You’re trying to live without enemies. That’s all you think about, not having enemies.” There is no haven of assurance, no comforts of resolution.

As a counterforce to the Cossacks, the Jews of Poland, with their “long bony backs, their tragic yellow beards,” pierce the taut objectivity of Babel’s stories, stirring in him a riot of memories, as in the opening of “Gedali”:

On Sabbath eve sad memories hang heavy on me. On Sabbath eve in days gone by my grandfather’s yellow beard would be brushing Ibn-Ezra’s heavy volumes. My grandmother in a lace cap would be making mysterious signs with her gnarled fingers over the Sabbath candle and softly weeping. My childish heart was rocked on such evenings like a little boat on enchanted waves. Oh, the mouldering Talmud of my childhood! Oh, the heavy sadness of memories!

Back and forth the narrator goes from the Cossacks—strange, cruel, and beautiful—to the Jews, “who moved jerkily…but whose capacity for suffering was full of a sombre greatness.” If Red Cavalry is a paean, ardent but ambiguous, to the force of revolution as realized in the bravery of the Cossacks, it is also an elegy for “the Sabbath peace [that] rested upon the crazy roofs of Zhitomer.” Nor is there any way to tell—at least I cannot—which of these conflicting responses is to be taken as dominant.

Red Cavalry offers no resolved judgment to be wrapped into a neat sentence; its “meanings” reside not only in the individual stories but in their interrelations.

The conflicts that course through Babel’s stories prompt one to reflect on the relation between literature and history. The very historical action that can lend urgency to a literary work can also, after a time, cause it to sink into a blur of the forgotten. In fictions with strong historical content, images of persons and places are vividly cast up and then, as time passes, are cast away. Such images are far removed from the “eternal” motifs that some readers like to regard as the true substance of literature. Perhaps these readers are right—finally, literature draws upon a small number of recurrent stories and motifs—but sometimes the writer’s imagination is fired not by a wish to transcend history but by a need to “capture” it, or by a wish to serve, at whatever cost, as a witness to his time.

In a well-known essay on Babel, Lionel Trilling elevated the problem of literature and history to a sort of timeless dialectic. “In Babel’s heart,” he wrote, “there was a kind of fighting—he was captivated by the vision of two ways of being, the way of violence and the way of peace, and he was torn between them.”

In the 1950s, when Trilling offered that judgment, serious people still gave credence to the high claims of the Russian Revolution, or could at least remember that they had once given such credence. But with the collapse of communism, it has become much harder to enter fully into the positive association Babel made with the revolution. A process of historical erosion has occurred, and in consequence it may be that Trilling’s ahistorical approach (“two ways of being”) serves Red Cavalry more persuasively than any insistence on seeing the stories as utterly entangled with the historical events and attitudes of their moment. But if we now incline to look with a cool eye on Babel’s response to the Russian Revolution, can we still share the intensity and excitement animating Red Cavalry?

The structural unit in most of the stories is the anecdote, but the anecdote wrenched out of traditional settings and yanked into modernism. A Babel story consists of a climax ripped out of its narrative situation, which, it is assumed, the reader can provide on his or her own. And what counts most is the writer’s voice—wry, stringent, now and then flaring into eloquence.

Those of us who lack Russian must be circumspect when talking about Babel’s style. Still, a few remarks may be ventured: in his stories the turmoil of violence can yield abruptly to a milky quietness. Objectivity seems the dominant mode, yet few prose writers would dare indulge in such lyrical apostrophes as recur in Babel’s pages. It’s commonly supposed that terseness and understatement go together, but not in Babel. Terse his stories are, but rarely are they understated. One moves with dizzying speed from abstraction to specific notation: surprise upon surprise. In some stories there’s a surrender to reflective sadness as complete as the rush to violence in others. In still others the crucial event is hidden, with the surface of the prose nothing more than a few ripples of talk. Speech inflicts wounds.

Babel composed frugally. Much of what he wrote during the 1930s he did not publish, composing, as they used to say in Soviet Russia, “for the drawer.” In 1934 Babel made one of his rare public appearances, at a Soviet Writers Congress. He said that he practiced a new literary genre: he was a “master of the genre of silence.” In the midst of routine praise for the party, he remarked as if in passing that it presumed to deprive writers of only one right, the right to write badly.

“Comrades, let us not fool ourselves; this is a very important right and to take it away is no small thing.” The right to write badly—to write from one’s own feelings, to make one’s own mistakes—it would be hard to imagine a sadder or more courageous word. Babel suffered no immediate punishment, other than the silence he imposed on himself, but from a few passages that can be culled from the letters he wrote to his wife, mother, and sister, all of whom had emigrated to Western Europe, we can gain some idea of what he thought and felt:

1925: Like everyone else in my profession, I am oppressed by the prevailing conditions of our work in Moscow; that is, we are seething in a sickening professional environment devoid of art or creative freedom. [In a few years he will not dare to write so openly.]

1928 (from Kiev): There’s poverty here, much that is sad, but it is my material, my language, something that is of direct interest to me…. I don’t mind going abroad on vacation but I must work here.

1930: As for the apparent misfortune of my literary life, up till now I have brilliantly allayed the fears of my short-sighted admirers and it will be the same in the future. I am made of a dough that is a mixture of stubbornness and patience and it is only when these two elements are strained to the utmost that la joie de vivre comes over me.

About Babel’s writings during the last several years of his life it is all but impossible to form a judgment. Manuscripts confiscated by the secret police remain unavailable, perhaps destroyed. How long could a writer continue to live with the rending oppositions that inform Babel’s work? I think that in some of his stories there are signs of a movement toward a plateau of moral balance, calmer and more contemplative than one finds in most of his work—though not necessarily making for a greater achievement. These signs of change, admittedly slight, suggest that he may have begun distancing himself from the pressures of his own mind. One might suppose that the mature Babel, knowing he had done as much as he could in the line of modernist brilliance, would have reached a moral ground somewhat beyond the brutal conflicts of his historical moment. But we don’t really know. The Babel we know is impaled on the agonies of our century, and perhaps that is where he would have chosen to stay. Ripeness was not to be his fate.

Babel was only forty-five when he was murdered. Thinking of his end, one feels again a helpless rage before the destruction Stalinism wrought upon a whole generation of gifted writers. Maxim Gorky had warned Babel: “A writer’s way is littered with nails, mostly large ones, and he has to walk on them barefoot. He will bleed profusely, and more and more every year.”