In 1712 King Louis XIV of France signed the lettres patentes that formally established Bordeaux’s Royal Academy of Sciences, Belles Lettres, and Arts, a social club of intellectual inquiry and public edification. In contrast to the more conservative University of Bordeaux, whose primary objective was to educate the country’s priests, doctors, and lawyers through lessons compatible with Scripture, the Bordeaux Academy saw itself as “enlightened”: its objective was advancing scientific truth as part of a larger program intended to promote “mankind’s happiness.”

Every year, the academy organized an essay contest that it publicized throughout Europe. In 1739 the members announced the subject of the competition for 1741: “Quelle est la cause physique de la couleur des nègres, de la qualité de leur cheveux, et de la dégénération de l’un et de l’autre?” (“What is the physical cause of the Negro’s color, the quality of [the Negro’s] hair, and the degeneration of both [Negro hair and skin]?”) Embedded in this question was the academy’s assumption that something had happened to “Negroes” that had caused them to degenerate, to turn black and grow unusual hair. In short, the academy wanted to know who is black, and why. It wanted to know, too, what being black signified. The winner was promised a gold medal worth three hundred livres, roughly the annual earnings of a common worker at the time.

The 1741 contest was only the latest iteration of non-Africans’ fascination with dark skin. When the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Arabic peoples first described the inhabitants of Africa, it was Africans’ color that struck them most. Over many centuries, African “blackness” grew into an all-encompassing signifier that substituted for the range of reddish, yellowish, and blackish-brown colors that the skins of Africans actually express. The color black also became synonymous with the land itself; many of the geographical names that outsiders assigned to sub-Saharan Africa—Niger, Nigritia, Sudan, Zanzibar—contain the etymological roots of the word “black.” The most telling example is the name Ethiopia. Derived from the Greek aitho (I burn) and ops (face), it became the most widespread label for the entire sub-Saharan portion of the continent until the late seventeenth century. It even hinted at the cause of blackness itself.

Over the course of 1741 sixteen submissions attempting to explain the source of blackness arrived at the Bordeaux Academy, from as far away as Sweden, Ireland, and Holland. Now housed in Bordeaux’s municipal library, this collection of manuscripts has survived the ravages of mice and moths, humidity and fire—not to mention the French Revolution and two world wars. One finds anything but consensus in this early modern focus group: there are biblical scholars who argue that blackness may have been a curse; climate theorists who affirm that Africans’ bodily humors—particularly their bile—have been thrown out of balance by the continent’s scorching heat; an anatomist who announces that he has discovered the secret of blackness while dissecting African cadavers on a New World plantation ; and an essayist who hints, four decades before racial taxonomies began to seduce European naturalists on a large scale, that he could classify “Negroes” as a specific race or even species. Taken as a whole, these essays do not yet reflect the assumed biological and cognitive inferiority that would soon be attributed to both free and enslaved Africans. Still, they certainly allow us to glimpse the insidious relationship between “science” and enslavement—and, to amend W.E.B. Du Bois’s resonant phrase, the dusk before the dawn of race.

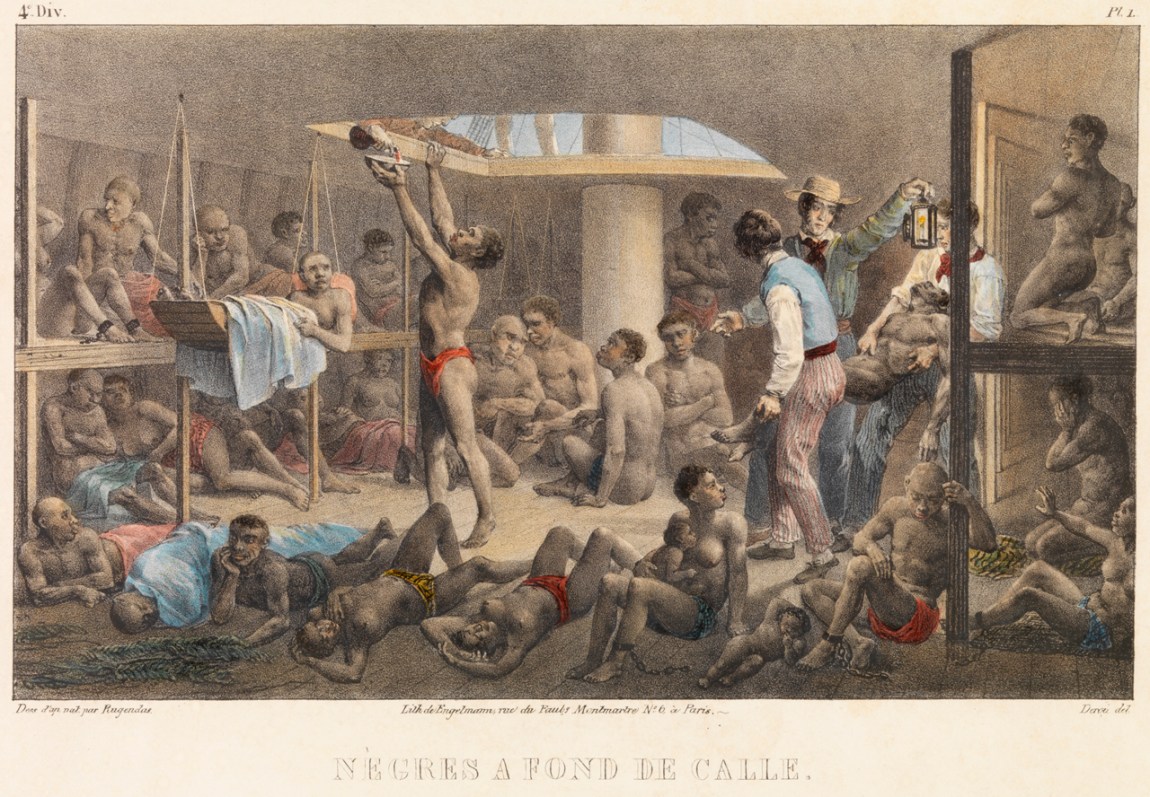

In announcing its competition on the origin of blackness, the Academy of Sciences made no mention of slavery. And yet, this seemingly clinical interest in specific African traits obviously emerged in tandem with the growing dependence on chattel slavery throughout the New World. In 1741—the year when the essays arrived at the academy—62,485 African men, women, and children in chains are estimated to have boarded ships along the west coast of Africa, destined for plantations in Brazil, Central America, the Caribbean, and North America. A disturbing number of these humans invariably died en route, 9,454 in this year alone. Although the transatlantic slave trade had not yet reached its peak, the number of Africans who had been forced to make this dreaded voyage already totaled well over four million. By the end of the eighteenth century, the era we have come to know as the Enlightenment, another 4.5 million Africans were forced to leave their home continent for a life of brutal enslavement in cities, farms, and plantations on the other side of the Atlantic.

Bordeaux, despite its position as a major Atlantic port city, remained a relatively minor player in the slave trade at the time of the contest. By 1837, however, the city’s armateurs (shipowners) had organized roughly five hundred expeditions to Africa, resulting in the deportation of approximately 150,000 Africans to French plantations. This figure represents approximately 13 percent of the 1.2 million enslaved Africans who survived the sea voyage and arrived in French colonies. It also far exceeds the total population of Bordeaux itself in 1789 (around 110,000).

Advertisement

Much of the wealth that was flooding into Bordeaux in the 1700s—the city’s so-called golden century—came from its ventures in the Americas, especially France’s three major colonies, Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Saint-Domingue (Haiti). By midcentury, Bordeaux’s relationship with the Caribbean helped transform its port into the busiest and most important anchorage in France, with more than thirty ships fully dedicated to the colonial trade in the Antilles. Ships leaving Bordeaux for the islands transported flour, lard, beef, ham, rolls of iron, copper utensils, pottery, roofing, hardware, tools, fabrics, clothing, and the weapons and ammunition used to control the islands’ Black populations. These same vessels returned to Bordeaux with cocoa, coffee beans, cotton, ginger root, and millions of pounds of muscovado sugar.

Profits from the colonial trade also funded some of the five thousand stone buildings, apartments, and opulent townhouses built during the era. The most visible evidence of Bordeaux’s colonial involvement in the Caribbean (and the slave trade) can be found on the façades of several eighteenth-century buildings near the old customs house on the banks of the Garonne. Looming above the massive portes-cochères, or covered entryways, of these former townhouses, mascarons (sculpted stone faces) with African features look down at the passersby below.

The forty members of the Bordeaux Academy by and large did not soil their hands in the transatlantic slave trade. (This is unsurprising since the academy did not admit merchants, even rich merchants, to its ranks.) And yet many academy members did have significant contacts with and financial interests in the French Caribbean. Some of the academicians belonged to aristocratic dynasties whose flagging fortunes had been revived by the royal allocation of plantations in Martinique or Saint-Domingue. This was the case for Nicolas-Alexandre de Ségur and for Louis-Charles Mercier Dupaty de Clam and his brother, Jean-Baptiste Mercier Dupaty; Jean-Baptiste was born on the family estate in Saint-Domingue. The academy also welcomed André-Daniel Laffon de Ladebat, François-Armand de Saige, and Pierre-Paul Nairac, all of whom came from families with ties to the slave trade. Nairac, with his two brothers, had actually been involved in the business himself; the family’s company had deported more than eight thousand African captives to the French colonies, more than any other syndicate or individual in the city.

All of these links to the Caribbean dovetailed with the academy’s larger “scientific” interest in developing knowledge related to French colonies generally and to the enslaved peoples on those islands more specifically. It was likely with this in mind that the academy admitted the Martinique-born botanist, colonial administrator, and plantation owner Jean-Baptiste Thibault de Chanvalon to its ranks in 1748.

Perhaps the most revealing moment of connection came, however, in 1738, when the aristocratic members of the academy who were simultaneously seated in the Bordeaux Parlement were called upon to pass judgment on the question of the legal status of the city’s Black population. Before 1716, enslaving a person in France was, at least theoretically, illegal; according to a royal principle dating from the fourteenth century, any enslaved person who set foot on French territory was immediately freed. In 1571 the Bordeaux Parlement had famously upheld this when a Norman slave trader arrived in the city and attempted to sell his cargo of African slaves. The parlement, citing the principle that “no one is a slave in France,” both freed the slaves and ordered the owner taken into custody.

The status of this so-called Free Soil principle was first called into question during the Regency (1715–1723), the interim period between the reigns of Louis XIV and Louis XV. In this age of rampant colonial expansion, Philippe d’Orléans, regent of France, proclaimed in 1716 that enslaved Africans from the Caribbean, whom the 1685 Code Noir deemed meubles, or property, were no longer automatically emancipated when they arrived on French soil. After four hundred years, slavery in France was once again legal.

Over the next two decades, an increasing number of enslaved Africans were taken to French cities, including Nantes, Saint-Malo, La Rochelle, Orléans, Paris, and Bordeaux. Bordeaux itself was home to several hundred enslaved Africans at any given time during the eighteenth century. Most of this Black population labored in or near the port, often for short periods before returning to the islands on merchant ships or, on occasion, escaping. Others lived with rich merchants or former ship captains, working as servants in some of the city’s great townhouses. Some came from the colonies to be trained as cooks, valets, or porters. A few of the youngest Africans to come to the city spent their early years as so-called négrillons, often represented in European art as devoted, even beloved extended family members hovering expectantly around their masters as living emblems of their power and opulence. It is estimated that some four thousand Africans or Caribbean-born Black people passed through or lived in Bordeaux during the eighteenth century.

Advertisement

By 1738 Louis XV felt compelled to issue a declaration clarifying the status of these Black populations. To avoid the fear of miscegenation, which was already a legal and social concern in the Caribbean, and the possibility of a “spirit of independence,” he limited the stays of enslaved Africans in France to three years. He also stipulated that those residing in France needed to be engaged in either religious or trade-related training. Owners who violated either part of this decree were to be fined a thousand livres and have their slaves confiscated and returned to the colonies.

In the year before the contest on blackness was announced, provincial parlements, including Bordeaux’s, were called upon to ratify or reject this declaration. The appellate judges who composed the Bordeaux Parlement—including a dozen or so men who were simultaneously members of the Academy—voted to accept Louis XV’s proposal. The ostensible goal of this statute was to control or even limit slavery in France; what it did, however, was further codify the legality of human bondage on French soil.

The presence of enslaved Africans in the city of Bordeaux surely contributed on some level to the genesis of the 1741 contest. Just what the Academy discovered from the competition was quite limited, however. Many essayists attempted to reconcile the origin of African skin with short biblical timescales, including the literalist reading of Scripture that maintained that God had created the earth precisely 5,741 years earlier. This powerful conviction intersected with providentialism, the belief that everything on earth is part of a larger divine plan.

Despite these shared beliefs, the religiously minded writers who contributed essays to the contest produced a wide range of explanations for blackness: that Adam or Eve was Black, or Adam was half Black; that blackness is a mark from God denoting sinfulness; that blackness is a gift from God allowing people to live in the “torrid zone.” Some of the essayists, however, attempted to combine their scriptural knowledge with more recent discoveries in the sciences. One asserted that blackness was passed down through the soul of the African father; another claimed that a moral defect in African parents had led God to make their progeny dark.

Several possible explanations for the source of blackness came directly from the Book of Genesis. The first of these was the curse of Cain, according to which Cain lied to God about murdering his brother Abel and was therefore “marked” or, according to some interpretations, “darkened”—a curse passed on to his descendants.

Far more convincing for some of the other essayists was the so-called curse of Ham or, more accurately, the curse of Canaan. According to this allegory, Noah fell asleep one night after drinking too much wine and lay naked and exposed to his three sons. The first two, Shem and Japheth, covered their father’s body to preserve his modesty. But Ham, his third son, had indiscreetly glanced at his sleeping father, an act of impropriety that led Noah to curse Ham’s only son, Canaan. Canaan was thus sentenced, with all of his descendants, to a life of slavery as a “servant of servants.” Several of the submissions to the contest not only cited this story but claimed that Ham had also undergone a physical “blackening,” a theory that had first been proposed by early Talmudic and Christian scholars in the third century CE.

The academy also received a number of climate-based explanations for blackness, all of which can be traced to the Greek physician Hippocrates and his belief that there was a causal relationship between extreme environments and the bodies of people living in such lands. Some of the contributors made use of these ideas to render the biblical story of Noah’s children slightly more scientific. This same understanding of the impact of the environment also allowed one thinker to identify the temperate European zone as the source of white people’s cognitive, aesthetic, and ethical preeminence. Anticipating what Montesquieu (a member of the Bordeaux Academy at the time of the contest) would write in his 1748 Spirit of the Laws, this contestant claimed, “It is only in intermediate regions, especially the warmer ones, that we find fertility and agile minds, an agreeable activity in external manners, and a delicate sensibility in pleasures.” These Eurocentric uses of climate theory were accompanied by more properly proto-racist and humoral notions that asserted that the heat, sun, and/or humidity of the torrid zone, bounded on the north by the Tropic of Cancer and on the south by the Tropic of Capricorn, had not only darkened African skin but may have thrown African bodies out of equilibrium, introducing imbalances that produced an excess of black bile, a condition supposedly leading to melancholia.

Climate theory also allowed some of the essayists to propose a far more dynamic understanding of nature and thus of humankind’s many varieties. One essayist not only claimed that an original white prototype group had degenerated in extreme climates; he proposed himself as a living example of climate’s ability to change one human type into another over time:

Although my [skin] color is the same as that of my [European] people, I am nevertheless the great-great-grandson of an Ethiopian who was brought from Africa to Germany by Emperor Charles V during the war in Mauritania, and whose children gradually turned from a black to a white color. Therefore, the truth is confirmed: the color of the Ethiopians is not inherent.1

Similar statements were also made about the potential mutability of white populations during the era: transport a family of Englishmen to the Congo, it was commonly asserted, and over the next two hundred years or so their descendants would degenerate and become black.

In May of 1741 the academicians met to discuss and debate the sixteen manuscripts in the academy’s headquarters. After a lengthy discussion—which was so shambolically recorded by the institution’s secretary that the resulting manuscript is virtually unreadable—they were disappointed to find that their contest had not solved the question of blackness. They themselves did not know what the right answer was, but they knew what the answer was not. Some of the men surely thought that the essays were not scientific enough; others were perhaps put off by naturalistic explanations that made no mention of God.

At some point, the members agreed that the contest was a failure. A short note in the Mercure de France stated that the Bordeaux Academy’s competition on blackness had received mediocre submissions. Following a procedure established in the late 1720s (after several other contests had concluded without a winner), the academicians presumably reallocated the prize money and purchased shares in the name of the academy from the Compagnie perpétuelle des Indes (Perpetual Company of the Indies). This new trade conglomerate, which oversaw all French slave trading in Africa after 1719, had been involved in the deportation of 37,000 Africans to the Caribbean by the time the contest concluded.

The Bordeaux contest, despite its failure and some especially fanciful submissions—one essayist was convinced that African mothers imprinted blackness on their fetuses through the power of the maternal imagination—did attract entries that anticipated the crystallization of race during the coming decades. In retrospect, one can see that material causes, be they linked to the environment or some humoral pathology, were beginning to trump religious explanations in many of the essays. Several submissions hinted that human phenotypes came about through some form of mutation over time.

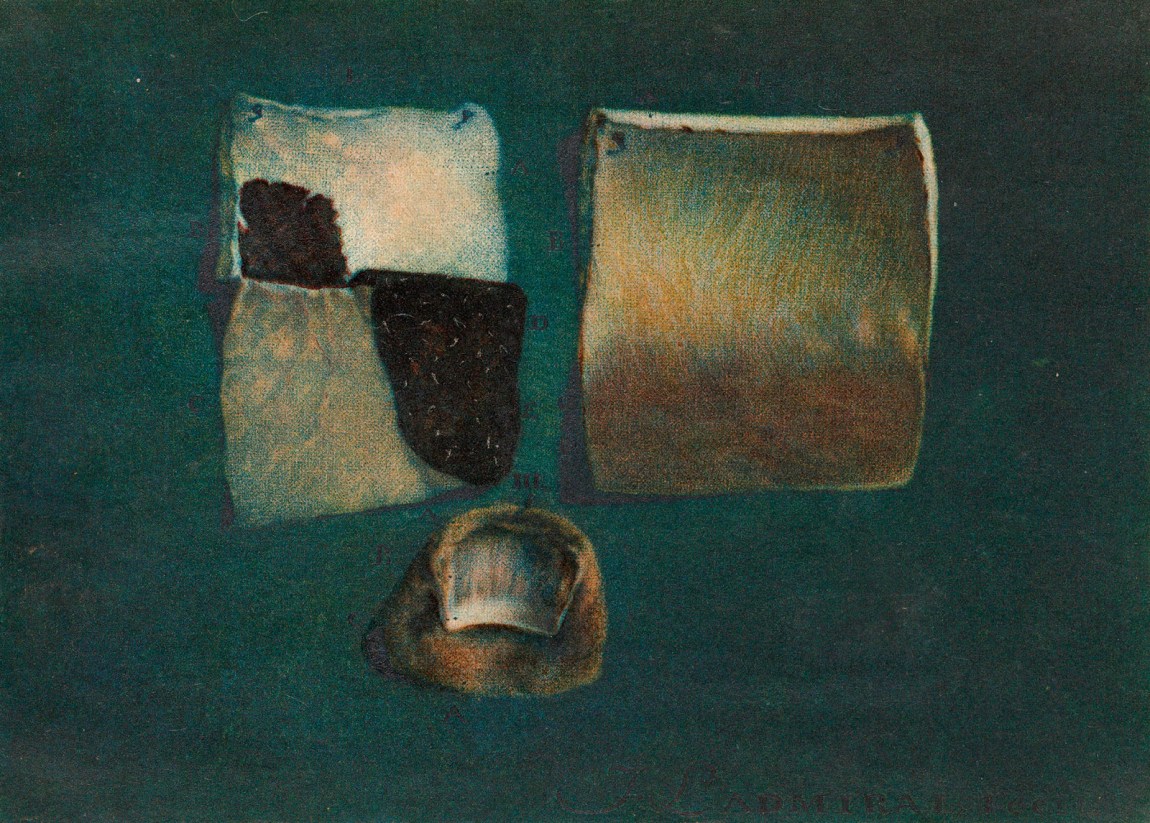

The one truly influential essay among the submissions was an “empirical” entry written by a physician and botanist named Pierre Barrère. Unlike the other contestants, Barrère had actual experience with Africans. Serving as a plantation surgeon in Cayenne (Guyana), Barrère had not only treated the enslaved men, women, and children who fell ill in the colony, but also conducted autopsies on members of this population when they died. Shortly after the contest concluded, Barrère published his Dissertation on the Physical Cause of the Color of Negroes, virtually the same text as the one he had submitted. In his short introduction, he claimed that he was encouraged to do so by the Bordeaux Academy itself.

To a certain extent, Barrère’s work harked back to an earlier generation of anatomists, especially Marcello Malpighi, the seventeenth-century Italian physician who discovered the rete mucosum, or Malpighian layer, the basal layer of skin where pigmentation resides. But Barrère’s aspirations went far beyond Malpighi’s; he was the member of a new generation of anatomists seeking out deeper (if fictional) physiological structures in African bodies. In the essay, Barrère declared that blackness was far more than the effect of the sun burning the skin; it was, he claimed to have discovered, a jaundice-like excess of dark bile that darkened the blood, a pathology that led not only to a rapid heartbeat but also to the extreme “lecherousness” of the Negro.

Barrère’s ideas echoed for decades. Seven or eight years after the contest concluded, the most important naturalist of the eighteenth century, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, read Barrère’s text while developing his own theory related to the African. Though he admitted that Barrère’s research seemed persuasive, Buffon attempted to downplay the importance of anatomy when discussing human varieties. Instead, he proposed a far more genealogical understanding of humankind—the story of a prototype group of white humans that slowly mutated into the world’s different human varieties as they moved into different climates. “All humans,” Buffon wrote, “are little more than the same man who has been adorned with black in the torrid zone and who has become tanned and shriveled by the glacial cold at the Earth’s pole.”

Buffon’s unease with the temptation of anatomy did not prevent a new generation of physicians from following Barrère’s lead. In 1755 the German anatomist Johann Friedrich Meckel announced that his dissection of a Negro man had revealed that Africans had bluish brains and darkened pineal glands; ten years later Claude-Nicolas Le Cat, a French anatomist working in Rouen, claimed that his own dissection studies had allowed him to identify an elemental black fluid, which he called oethiops, that coursed from the African’s brain through to the nerves, organs, skin, and even sperm. These and other “breakthroughs,” which were generally received as fact, were quickly disseminated in scientific journals. They even appeared in Diderot’s Encyclopédie.

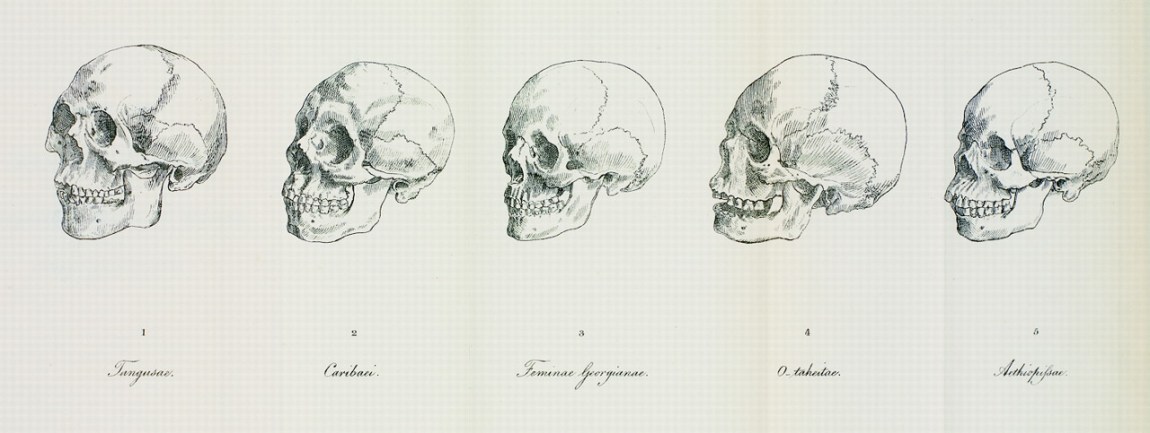

The anatomical explanations of blackness that emerged in the 1750s and 1760s coincided with a more essentialized, or racialized, classification of Africans. In 1758, in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae, Carl Linnaeus reduced Americans, Europeans, Asians, and Africans to specific zoological phenomena based on pigmentation, humoral tendencies, physical traits, temperament, clothing, and political orientation. Linnaeus’s classification of the so-called Homo africanus was withering; among other things, he described Black Africans as flat-nosed and thick-lipped, lazy and phlegmatic. He wrote that African women had elongated labia and profusely lactating breasts. He also claimed that, while European society was based on law, the governing principle of the African people was caprice.

Classifiers and anatomists were not the only thinkers contributing to a far more deterministic understanding of the African (including the “African mind”) in the 1750s; two of the era’s most celebrated Enlightenment philosophers, David Hume and Voltaire, chimed in as well. Both of these sworn enemies of intolerance identified “Negroes” as a distinct and inferior species. Hume’s most notoriously racist screed came in an endnote that he added to the revised 1753 edition of his essay “Of National Characters.” In addition to asserting that human beings come in “four or five different kinds,” Hume—who was recently revealed to have facilitated the purchase of several plantations in the Caribbean—maintained that one could survey the entire African continent and find “no arts, no sciences” among its peoples—a statement that not only denied Black Africans the ability to reason, but reason’s necessary corollary, civilization. To further his point, Hume belittled Francis Williams, the free Black poet from Jamaica who had become well known in London for his Latin-language odes. Though Hume had never met Williams, he described the poet as a “parrot, who speaks a few words plainly.”

Three years later, Voltaire added his own eerily similar indictment of Africans’ ability to think and to reason in his 1756 Essay on Universal History, the Manners, and Spirit of Nations. As he put it:

The race of Negroes is a species of man different from our own, in the same way that the breed of spaniels is different from that of greyhounds…one could say that if their intelligence is not of a different species from our own, it is far inferior. They are not capable of much attention. [Negroes] combine few ideas and do not appear to be made for either the advantages or the disadvantages of our philosophy.

It was in Germany, however, where the idea of a national character or spirit reached its full expression—where reason was ultimately painted white. This process began when Immanuel Kant responded directly to Hume’s musings on national character in his 1764 Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and the Sublime. Ranking human races by their supposed cognitive aptitudes, the German philosopher declared that black-skinned Africans lacked any “feeling that rises above the trifling.” This, he maintained, was directly related to the fact that being “black from head to foot” was not simply a matter of pigmentation, it was clear proof that Africans were, by definition or a priori, “stupid.”

In his subsequent anthropological writing, Kant continued to assert that black skin corresponded to a lower cognitive potential, a lack of reason, and an inferior and unchanging moral character—all of which prevented Africans from reaching the state of civilization.2 These views became the foundation of his seminal 1777 essay, “Of the Different Human Races,” in which Kant provided the first philosophically rigorous definition of race, one that not only asserted the biological permanence of racial categories—“(1) the race of the Whites, (2) the Negro race, (3) the Hunnish (Kalmuck or Mongolian) race, (4) the Hindu or Hindustani race”—but positioned the African race as seemingly less than fully human, a group whose fundamental liabilities were “unchanging and unchangeable.”3

This was no longer the dusk before the dawn of race; it was the first light of scientifically rigorous racism: an era when naturalists and taxonomists divided the world’s peoples into discrete subspecies, when skin color and category became synonymous with racial destiny.

The human classification schemes that came into existence in the 1770s and 1780s lent tremendous authority to scientific falsehoods—especially those related to Black Africans, people of African descent, and black skin. Nowhere is this more evident than in Thomas Jefferson’s discussion of the Black people whom he had come to know in his capacity as plantation and slave owner. Commenting on a litany of anatomical information on Africans—some of which comes directly from the essay that Barrère submitted to the Bordeaux Academy—the future president of the United States wrote in his 1787 Notes on the State of Virginia:

The first difference [between Blacks and Whites] which strikes us is that of color. Whether the black of the negro resides in the reticular membrane between the skin and scarf-skin, or in the scarf-skin itself; whether it proceeds from the color of the blood, the color of the bile, or from that of some other secretion, the difference is fixed in nature, and is as real as if its seat and cause were better known to us. And is this difference of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty in the two races?

Like many eighteenth-century thinkers, including the members of the Bordeaux Academy, Jefferson remained unsure just what constituted the physical essence of blackness. Yet he shared the belief that the “fixed nature” of black skin was undoubtedly rich with taxonomical and political significance. The debate had shifted from the cause of blackness to its effect.

As the notion of biological races began coalescing throughout Europe, the Bordeaux Academy of Sciences began thinking about Africans from a supposedly more enlightened point of view. In 1741 the Academy presented the riddle of blackness as a strictly scientific problem—an almost apolitical quandary having nothing to do with the fact that millions of Africans were enslaved in European colonies at the time. Thirty years later, the institution finally acknowledged the reality of slavery. In 1772 it organized a prize-problem focused on the dangers of the deadly Middle Passage: “What are the best ways of preserving Negroes from the diseases that afflict them during the crossing to the New World?”

The motivation behind this appalling contest reflects a forgotten trend during the first years of the abolitionist era: the notion that, through science, slave traders and planters could reform, rationalize, and “improve” existing enslavement practices, moving the colonies toward a form of bondage that was supposedly more benevolent. Emblematic of the academy’s belief in both philanthropy and practicality, this contest was clearly designed to promote a more “humane” crossing for the slaves who were enriching Bordeaux’s economy—while also helping ship captains and their owners decrease mortality and thereby increase profits. Such were the limits of the era’s humanism and universalism: the Enlightenment’s quest to improve the human condition seemed perfectly compatible with the economic imperatives of African chattel slavery.

Though the academy ultimately extended the entry dates for the contest, it received only three submissions. Two had abolitionist leanings that the members probably did not find suitable. The reliability of the third, which had been sent in by a Bordeaux apothecary, was called into question by someone inside or outside the academy. In 1778, the academicians decided to abandon the Middle Passage contest as well.

For the next fifteen-odd years, the academy went back to its business of organizing public events and competitions. In 1793, however, France’s revolutionary government abolished institutions that, like the academy, were bastions of aristocratic privilege and power. Bordeaux’s Royal Academy of Sciences was no more.

This was the least of the city’s problems at the time. In the 1790s, uprisings in the richest colony in the world, Saint-Domingue, disrupted the critical economic ties that Bordeaux had maintained with the Caribbean. At the end of 1793 more than half of the remaining colonists from Saint-Domingue returned to France, most of them to the Bordeaux region. Eleven years later, the revolutionary leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines declared Haiti an independent republic. Bordeaux’s “golden century” had come to a close.

The legacy of the Bordeaux Academy’s failed contests remains a footnote—largely forgotten during the eighteenth century, even less remembered today. The only prominent traces of the first international contest on blackness, in fact, are found in the most famous book of the eighteenth century, Voltaire’s Candide, published in 1759. Candide, who is traveling with an enormous red sheep that he had acquired in the utopian country of El Dorado, arrives in Bordeaux on his way to Paris. Candide realizes that he can no longer take care of his exotic pet and donates the animal to the Bordeaux Academy of Sciences. The academy, according to Voltaire’s story, saw the sheep’s unusual color as an excuse for yet another competition and quickly “proposed a prize competition for that year on the subject of why the wool of this sheep was red.” The winning scholar, as the story goes, “demonstrated by A plus B, minus C, divided by Z, that the sheep had to be red and would die of the mange.”

-

1

The unnamed ancestor of the Bordeaux essayist was presumably taken back to Germany in the aftermath of the conquest of Tunisia in 1535 by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. His subsequent success and integration into European society, while not common, was not entirely extraordinary. Other famous people of color in this category include Juan Latino, the sixteenth-century Spanish scholar of classical Latin at the University of Granada; Abram Petrovich Gannibal, who not only served at the court of the reformist tsar Peter the Great but was the great-grandfather of the renowned novelist and poet Alexander Pushkin; the philosopher Anton Wilhelm Amo, who held important teaching posts at the universities of Jena and Halle, in Germany, in the mid-eighteenth century; Jacobus Elisa Johannes Capitein, who studied at the University of Leiden and in 1742 produced a dissertation on the Christian defense of slavery with no apparent irony; and Angelo Soliman, born Mmadi Make in 1721, who became an upper-class member of Enlightenment Viennese society. ↩

-

2

See N.G. Jablonski, “Skin Color and Race,” American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol. 175, No. 2 (June 2021). The authors would like to thank Professor Jablonski for her generous clarification of a number of issues in this article. ↩

-

3

Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, “The Color of Reason: The Idea of ‘Race’ in Kant’s Anthropology,” The Bucknell Review, Vol. 38, No. 2 (1995), p. 219. ↩